In the spring of 2020, the European Union announced an ambitious plan to overhaul farming practices in fields and valleys across the continent. Named Farm to Fork, it calls for less fertiliser and pesticide use, and more organic production.

Veteran sustainable food and farming experts welcomed the strategy as one that just might have a genuine shot at transforming the agriculture sector and result in better public health, contribute to ending the vertiginous decline of biodiversity, and lower greenhouse gas pollution.

The response from Europe’s powerful industrial agriculture sector was swift and unequivocal: Farm to Fork will result in disaster. “Lower yields”, “higher food prices”, “unviable incomes for farmers”’ are among the outcomes predicted by an army of Brussels lobbyists, who are employed by the agrochemical industry and its allies in the intensive farming sector.

Since 2020, the world’s four largest pesticide companies have spent over 20 million euros on lobbying both EU officials and the public. In that time, they have issued dire warnings on the impacts of Farm to Fork in newspapers, at conferences, and during private meetings.

A Liveable Future at Stake

The battle over agrochemical regulation is not new. Pesticides and fertilisers have transformed agriculture over the past 70 years, and environmentalists have protested the ecological damages they cause in step.

But now Europe is poised to enact laws that would not only recognise the harms of chemical-intensive agriculture, but also to ensure that synthetic pesticide and fertiliser use is significantly reduced. The targets are steep: to cut pesticides by 50 percent and fertilisers by 20 percent by 2030.

As the Farm to Fork strategy begins to crystallise into law, campaigners believe that the agrochemical and other farm-related industries are increasingly desperate to control the conversation before European farming is irreversibly redefined.

One in ten bee and butterfly species are endangered in Europe and chemical pesticides are a major driver – over a million EU citizens have called for pesticides to be phased out.

New analysis by DeSmog has identified the key arguments that Big Agriculture is using – on repeat – to cast doubt and slow down the implementation of green framing reforms.

“These narratives have been effective,” according to Nina Holland of the watchdog group Corporate Europe Observatory, leading to “various important plans postponed or swiped off the table for the foreseeable future”.

DeSmog’s analysis also shows that European agribusiness has borrowed from Big Oil’s lobbying playbook, with arguments that echo tried and tested tactics and messaging used by the oil and gas industry to block action on climate change.

“The fossil fuel industry has bought itself half a century,” said Jennifer Jacquet, an associate professor of environmental studies at New York University, and author of The Playbook: How to Deny Science, Sell Lies, and Make a Killing in the Corporate World. She wonders how much time the agrochemical industry will be able to buy, warning that “a liveable future is at stake”.

Big Ag’s Delay Tactics

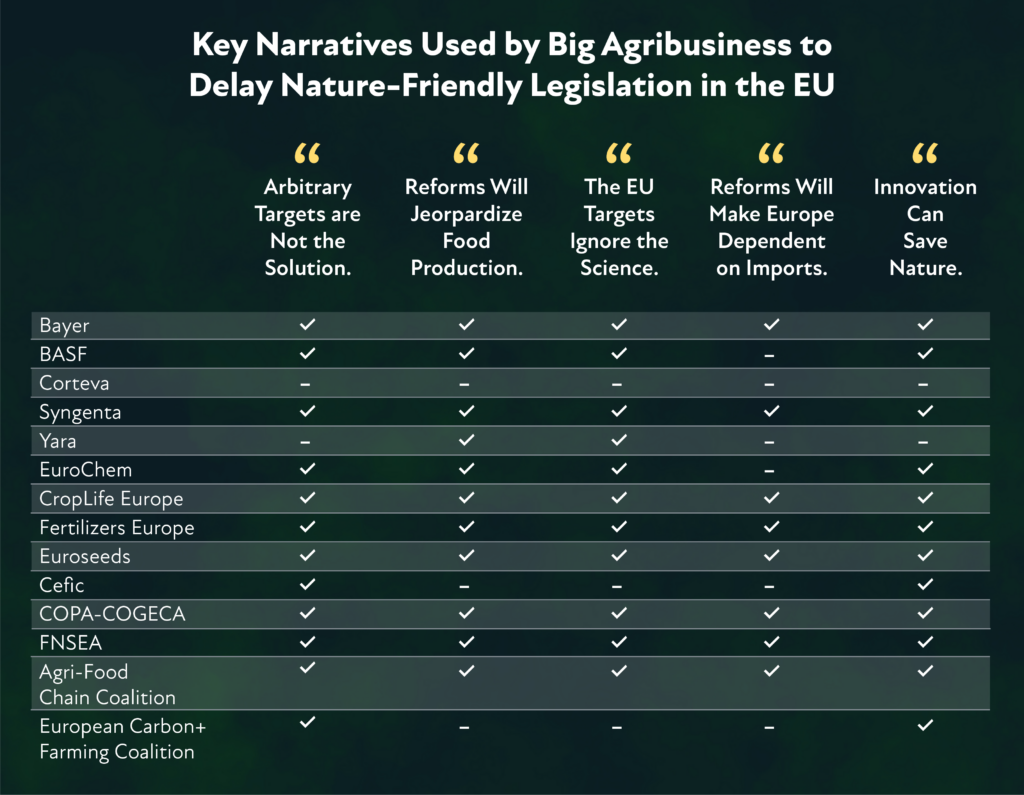

DeSmog has identified five “narratives of delay” in documents put out by powerful actors in the agrochemical and industrial farming industries since the EU announced Farm to Fork.

As our sample, we took the communications of 14 EU players who were identified in a 2021 DeSmog investigation as key opponents of EU environmental policy reforms. (See Table.)

They include some of the world’s largest pesticide, synthetic fertiliser, commercial seed and agricultural companies – BASF, Bayer, Syngenta, Corteva Agriscience, Yara International and EuroChem Group – as well as several powerful trade associations or unions – CropLife Europe, Fertilizers Europe, Euroseeds, the European Chemical Industry Council or Cefic, Copa- Cogeca, and the Fédération nationale des syndicats d’exploitants agricoles or FNSEA – and two industry-dominated multi-stakeholder groups – the Agri-Food Chain Coalition and the European Carbon+ Farming Coalition.

A full data set of the evidence behind this table is available on request from DeSmog. It can also be viewed in DeSmog’s Agribusiness database, which includes profiles of all the above listed companies.

We reviewed corporate reports, lobbying records, official position papers, responses to public EU consultations, minutes of meetings with EU officials, media events, and third-party civil society and news reports.

We also spoke to sources from within EU decision-making bodies and related civil society groups.

The research considered both “inside” lobbying efforts to directly influence policy through formal interactions with policymakers, and “outside” lobbying aimed at swaying public opinion.

The analysis showed the same messages being used by multiple allied players. It found arguments that undermine green targets – by branding them as unscientific, for example, or likely to ruin Europe’s farmers – are repurposed and repeated in public consultations and during meetings with legislators, in media statements and social media posts.

All organisations in this investigation were contacted by DeSmog for comment.

Bayer told DeSmog that while it “welcomes the objectives of the EU Green Deal […] there are still open questions in terms of concrete implementation”, including of the pesticide reduction targets.

BASF said it “see[s] no point in questioning the Green Deal or Farm-to-Fork strategy” and that it “acknowledge[d] societal expectation” to reduce pesticides.

Chemical body Cefic said their President Martin Brudemüller’s comments, which DeSmog reviewed in its analysis, “did not reflect” the organisation’s position but that of Brudemüller’s company BASF, where he is chief executive. Cefic stated that it did not lobby on Farm to Fork or pesticide targets, affirmed its support for the Green New Deal and stated its ambition to be “climate neutral” by 2050.

Major fertiliser company Yara informed DeSmog of its commitment to decarbonising EU’s agriculture and the overall industry. It said: “fertilisers are a key piece of the puzzle to keep up with EU’s ambition to produce food in a more sustainable way”.

1. ‘Arbitrary Targets Are Not The Solution’

The Big Ag lobby in Brussels has repeatedly suggested that the EU should not focus on legally binding cuts in agrochemical use, and sought to replace the ambitious targets already agreed by the European Parliament with weaker alternatives.

While the industry states that it is not against the principle of setting targets, it has opposed them in practice, labelling EU targets in the “SUR” pesticides-reduction plan as “non-data based”, “unrealistic”, “pointless” and “counterproductive”.

Industry has lobbied hard to ensure these targets don’t become law. In 2021, for example, farm lobby COPA-COGECA sent MEPs numerous industry-friendly amendments to the sustainable farming strategy – and suggested the removal of commitments that would make targets legally binding.

Instead, the message – which echoes positions often used by the fossil fuel lobby – is that EU policy should optimise incentives. As pesticide trade body CropLife Europe says: “let’s focus on transition, not just targets”.

In a November 2022 letter to a key EU policymaker, multiple agribusiness lobby groups – including COPA-COGECA, pesticide trade group CropLife Europe, and seed trade group Euroseeds – argued that the targets should be replaced with ones that are “based on science and feasible for producers”.

But experts say that creating a legally binding framework for Europe is crucial. Christian Huyghe, scientific director of agriculture at French research institute INRAE, told DeSmog that the Europe-wide targets are necessary to ensure a level playing field. Otherwise, he suggests, countries will refuse to make changes on the perception that their neighbours are not taking equivalent action.

2. ‘Reforms Will Jeopardise Food Production’

Central to the industry’s fight against targets are scare stories about potential economic and political upheaval that could result from cutting back pesticides and fertilisers.

Industry lobby groups such as Croplife Europe say that the measures will put European food production at risk.

According to pesticide firm Syngenta, targets could endanger food security (“Lower yields mean more people go hungry”) while a COPA-COGECA representative has warned of the risk of green reforms at a time of volatile food prices that risked political unrest and even a refugee “crisis”.

Industry has also opportunistically repurposed this argument in light of the war in Ukraine. Earlier this month, DeSmog revealed that COPA-COGECA had told EU officials to revise and delay Farm to Fork at what it termed a “critical moment” for food security due to the war.

The message that “the green transition will come at an unacceptable social cost” echoes a story often heard from the fossil fuel lobby. Experts say that this narrative is misleading on multiple fronts.

The impact of the targets will depend on how they are implemented, scientists explain. Huyghe from INRAE notes that Europe can reduce pesticides without any fall in yields if proper support is given to agroecological innovations.

Even if yields did drop, many point out, this needn’t endanger food security. According to the United Nations, farmers already grow more than needed to feed the world’s population. Scientists at Lancaster University have found that – with an overhaul of diets and distribution – we could meet the nutritional needs of up to 9.7 billion people in 2050 even with current production levels.

Most important of all, academics, campaigners, and the European Commission, say the impacts of failing to act on the extinction crisis far outweigh any predicted negative impacts of green reforms.

Biodiversity loss, driven in part by chemical-intensive farming, is a major threat to food production, points out Pierre-Marie Aubert, director of the agriculture and food policy programme at think tank IDDRI. “We need to radically decrease pesticide use,” he says, “if we’re serious about being able to farm the land in fifty years time.”

Fertiliser giant Yara said DeSmog’s interpretation of the company’s position on food production was “misleading”. It said: “For the Farm to Fork vision to succeed, the entire food chain needs to share responsibilities for improving the environment by halving nutrient losses. Yara will do its part and empower farmers to rise to the challenge”.

3. ‘The EU Targets Ignore Science’

The industry often claims that green targets are “political”. And the EU’s proposed reforms, they say, do not take into account science and data that predict negative impacts.

To drive this message home, the industry has underwritten no less than five “impact assessments” modelling the effects of the Farm to Fork strategy on different agricultural sectors. Three of these were commissioned by groups that DeSmog included in its analysis: CropLife Europe, COPA-COGECA and Euroseeds.

Two of the five impact studies were conducted by Wageningen University and Research, the private consultancy arm of a Dutch public university. At the time, Wageningen President Louise O. Fresco was a member of the Syngenta board of directors. BASF and Anglo-Dutch oil company Shell had funded professorships at the university.

The industry’s predictions that Farm to Fork’s agrochemical targets will decrease food production rely on the findings of these studies, which its lobbyists have promoted in Brussels.

It’s a familiar tactic for Big Oil, which has poured millions into funding “independent” scientific and economic studies, including paying economists to estimate the costs of climate policies. The results “inflated predicted costs while ignoring policy benefits […] undermining numerous major climate policy initiatives”, according to a study from Stanford University.

Campaigners, academics, and the European Commission have pointed to parallel flaws in the agribusiness-funded studies. According to Jereon Candel, associate professor of food & agricultural policy at Wageningen, they fail to account for the positive impacts of meeting the targets, such as how a thriving bee population benefits crop pollination.

The studies also don’t consider parallel developments that could help offset potentially lower harvests, such as dietary shifts (a limitation highlighted in one of the Wageningen studies) or agroecological innovations (an omission that INRAE’s Huyghe says is crucial).

Again, the research doesn’t account for the cost of inaction. In October, a study by the German government’s Environment Agency found that the annual costs of biodiversity loss due to intensive agriculture alone in the country amounted to 50 billion euros – far outstripping the potential economic costs of implementing the EU’s new pesticide regulations.

4. ‘Reforms Will Make Europe Dependent on Imports’

Another key industry message warns that targets will “destroy” Europe’s agriculture and make its member countries dependent on imported produce.

Farm to Fork’s mandates for 50 percent less pesticide and 20 percent less fertiliser use by 2050 could turn the EU into a “a net importer of calories”, according to COPA-COGECA, and simply displace carbon emissions to countries with weaker regulations.

Agrochemical and farming lobbies argue that an increase in food imports along these lines would be a “perversion” of the legislation’s eco-friendly aims.

This message repurposes Big Oil’s “free-rider theory”: the idea that if some, but not all, nations enforce climate regulations, carbon pollution (and industry profits) will simply be transferred elsewhere.

Academics and campaigners say that these arguments are misleading and even factually inaccurate.

When it comes to imports, according to research by IDDRI, INRAE and French university Sciences Po, the EU is already a net-importer of calories. However the 2021 study found that if greener farming practices were combined with measures such as dietary changes and slashing food waste, Europe could transform to a net calorie exporter.

Wolfgang Cramer, research director at the Mediterranean Institute for Biodiversity and Ecology, told DeSmog that the risk of emissions moving overseas is a real concern. But suggesting that this is a good reason against taking action is “a cheap argument that doesn’t hold”.

The climate and biodiversity crises demand leading by example, said Cramer, who contributed to the 2021 UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report on climate breakdown, called the Sixth Assessment Report.

If Europe takes action, he believes, it will be in a more powerful position to demand that all nations act on the climate and biodiversity crises.

5. ‘Innovation Can Save Nature’

Big Ag maintains that there’s a different solution to the biodiversity and climate crises. In the words of chemical giant BASF: “We need to shift the focus from reduction to innovation”.

Industry is widely promoting one such innovative approach, dubbed “climate-smart agriculture”. The European Carbon+ Farming Coalition, a multi-stakeholder group that includes four of the world’s largest agrochemical companies, promotes the message that methods falling under this category – from sustainable ag basics like using cover crops to tech-intensive “precision farming” – could make significant cuts to greenhouse gas emissions, massive improvements in soil health, and increase farmer income.

The industry’s advocacy of climate-smart agriculture strikes some campaigners as an attempt to distract the public and policy makers, akin to Big Oil’s promotion of “techno fixes” like carbon capture and storage, which are unproven at scale. According to GRAIN, a group that supports small farmers, “the ‘climate smart’ label can be applied to pretty much all practices of industrial agriculture”.

Techniques bundled under the “climate smart” label also have the potential to generate big profits for major industrial players. Bayer, BASF, and Syngenta – all members of the Carbon+ Farming Coalition – each own “digital agriculture” platforms dedicated to use of precision farming techniques. These apps help farmers “optimise” their use of inputs like pesticides and fertilisers, for instance. Innovations like these are promoted as the only way to “combine sustainability and food security”, as Bayer put it to DeSmog.

While scientists agree that such techniques may allow farmers to use less chemicals, they also ensure that they’ll continue to be used. Friends of the Earth argues that companies can use these platforms to “extract data from farmers,” direct them to the company’s own agrochemical products, and “lock” them into driving company profits.

Precision farming focuses on “efficiency”, said Huyghe from INRAE, “when what we need is reconception”.

Dominating the Conversation

Agribusiness employs an army of lobbyists in Brussels. It makes sure policymakers are hearing these five core messages over and over in response to the European Green Deal, the Farm to Fork Strategy, and corresponding legislation ranging from the Sustainable Use of Pesticides Regulation (SUR) to the Biodiversity Strategy.

Credit: Clare Carlile, Michaela Herrmann, and Gaia Lamperti

The four largest pesticide firms employed over 40 lobbyists last year. Companies also use their vast resources to employ multiple “lobby outfits”, Nina Holland from Corporate Europe Observatory told DeSmog.

One of these is public relations firm Hume Brophy, which previously lobbied for Peabody Energy – a coal company linked to climate science denial – and the World Coal Association. Hume Brophy has lobbied on various elements of the green farming strategy for clients that include Bayer and Euroseeds.

Members of the industry also club together through trade bodies and associations. Groups like CropLife Europe, Fertilizers Europe, Euroseeds, and Cefic enjoy significant clout in EU spaces, and are regularly invited to speak at major conferences and provide their expertise as part of advisory groups that guide the commission on everything from fertiliser products to its soil strategy for 2030.

US academic Jacquet told DeSmog that arms-length trade bodies help companies create multiple and contradictory narratives – allowing them to support green reforms, while simultaneously opposing action. “The companies say ‘we are pro-science, we are pro-policy, we are pro-public health’, but then they fund the trade groups to do the dirty work,” she said.

With just a handful of the same companies dominating the seed, fertiliser and pesticide sectors, the membership of these trade bodies overlap. That means that the preferred messages of a few companies are heard many times over in a decision making process. For example, members of advisory bodies that assist the European Commission to draft and implement legislation – called “Expert Groups” – sometimes represent a much smaller range of voices than it appears.

Earlier this month, DeSmog revealed that 80 percent of the members and observers of the “Expert Group on the European Food Security Crisis Preparedness and Response Mechanism” – a multi-stakeholder group convened by the European Commission – were from industry. Four of the trade associations in this group represent BASF, three represent Bayer, and two represent Syngenta and Corteva. Members of the Expert Group have repeatedly advocated for “slower” implementation of the EU’s green farming plans during advisory meetings.

Trade associations like CropLife Europe and Euroseeds have affiliates in countries across the world. When the interests of their members are threatened, they have ready-made local alliances ready to speak up on their behalf. So while 89 business associations from across Europe responded to the EU’s September consultation on the new pesticide laws, one in every eight groups represented Bayer.

When not speaking to decision-makers directly, these industry groups have access to an array of different platforms to get their message out in the press, on social media and at high-profile events.

CropLife Europe pays for sponsored op-eds in the Brussels press; Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta and Yara secured speaking slots alongside European officials as sponsors of major events such as Politico’s 2022 Future of Farming Summit last September. And social media channels are a useful platform to spread ideas for lobby groups such as Euroseeds, which shared a Facebook post in January 2022 that stated Farm to Fork would lead to an extra 3.6 billion tons of greenhouse gas emissions before 2040.

‘Deadlock’ for Green Farming Reforms

With green reforms moving at a snail’s pace, industry arguments seem to be finding their mark.

The EU has already twice delayed key elements of its green farming plans following industry demands.

The European Commission has just complied with calls by 20 member states for new pesticide laws to be reassessed – a demand repeatedly made by industry since the new targets were first announced in 2020.

This has effectively stalled negotiations over pesticide-reduction targets for individual member states until further notice.

“The number one call industry makes is always for more research,” said US academic Jacquet, who recognizes this as a tactic of Big Oil. “It buys more time to prevent regulations”.

EU countries are also making arguments against targets that are startlingly similar to the industry’s five delay narratives, citing concerns over the war in Ukraine, potential decreases in yields, and referencing “widely shared concerns” about the bloc exporting its pollution abroad.

According to Tjerk Dalhuisen from campaign group Pesticide Action Network Europe, not only the agrochemical regulations are at stake. If they are jettisoned, he said, “it could derail” other legislation in the EU’s sustainable farming plans.

Delays in implementing green laws can be as valuable to industry as all-out opposition. Many green campaigners and politicians fear that if the sustainable farming measures are stalled beyond the election of the new European Commission in 2024, they may be forgotten entirely.

With pollinator numbers plummeting and soil health in collapse, experts say that major reforms are needed to ensure that the land can produce enough food in the decades to come.

Jacquet expressed confidence that Europe could still make these reforms. “Industrial farming was once a whole new way of doing things: we can reinvent ourselves again,” Jacquet told DeSmog. “I worry only about the time.”

Additional research by Michaela Herrmann.

DeSmog has published new profiles in its Agribusiness Database, which inform this investigation. The entries, which collate company and lobby groups’ positions on climate and biodiversity, include: the Agri-Food Chain Coalition, the American Chamber of Commerce to the EU, EuroChem, the European Carbon+ Farming Coalition, Euroseeds, FNSEA, Hume Brophy, International fertiliser Association and Wageningen University and Research.

We have also updated our profiles on BASF, Bayer, COPA-COGECA, Glyphosate Renewal Group, Syngenta and Yara.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts