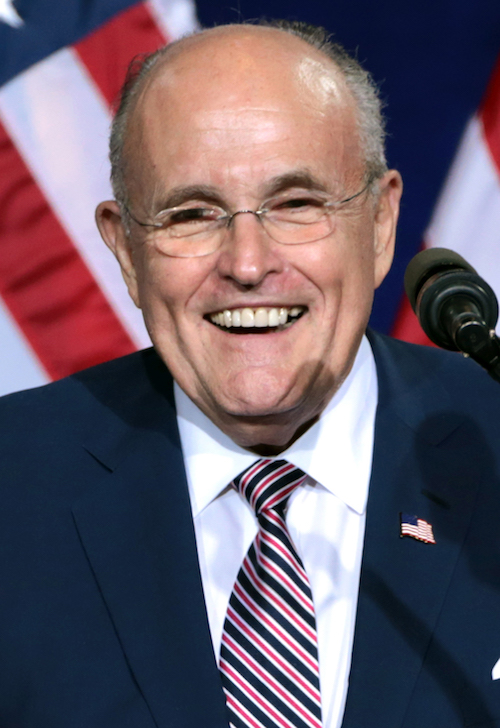

Rudolph W. Giuliani

Credentials

- J.D., cum laude, New York University School of Law, 1968.1“RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 13, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/N4Ci7

- B.A., Manhattan College, 1965.2“RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 13, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/N4Ci7

Background

Rudolph (Rudy) Giuliani served as the Mayor of New York City for two terms, from 1994 through 2001, and was a 2008 Republican presidential candidate. He is the Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of Giuliani Partners LLC, which he founded in January, 2002. He was appointed the Associate Attorney General under President Reagan in 1981.3“Rudolph W. Giuliani: Chairman & Chief Executive Officer,” Giuliani Partners. Archived February 6, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/sYxuW 4“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

When Giuliani launched his presidential bid in 2007, Time magazine dubbed him an “honorary Texas oil lawyer.” By October of that year, he had raised more than half a million dollars from the oil and gas industry, more than the next two top recipients combined. Giuliani began work at Bracewell & Patterson—later renamed Bracewell & Giuliani—in 2005. During his presidential bid, over $14,000 of his total campaign dollars came from the oil refiner Valero Energy, one of Bracewell & Giuliani’s clients. Giuliani left Bracewell & Giuliani in January, 2016, and the firm subsequently rebranded itself as Bracewell.5“Giuliani Leaps Past 0,000 Mark in Big Oil Contributions,” Consumer Watchdog, October 19, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/Dh5Ju 6Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016. 7(Press Release). “BRACEWELL ANNOUNCES THAT MAYOR RUDOLPH GIULIANI WILL LEAVE FIRM BY AMICABLE AGREEMENTMOVING ON TO OTHER CHALLENGES,” Bracewell, January 19, 2016. Archived December 12,2 016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/GciyE

Giuliani appeared to reflect his client’s interests on the campaign trail and beyond. Over 2007 and 2008, Giuliani indicated he would open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil drilling, came out against fuel economy mandates for cars, said the United States would be “better off if we could rely somewhat more on our coal reserves” in order to achieve energy independence, and supported coal-to-fuel synthesis, believing it could be “a very valuable contributor” to said independence.8“Giuliani’s Green Record,” Living on Earth, September 14, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/JZgFD 9“‘Meet the Press’ transcript for Dec. 9, 2007,” NBC News, December 9, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/NRbD3 10Christian Giggenbach. “Giuliani touts importance of coal,” The Register-Herald, August 3, 2007. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/hNDTO

Giuliani Declined Positions in Trump Administration

Before making the surprise announcement that he was pulling out of consideration for a cabinet post in the Trump administration, Giuliani was one of the contenders for the position of Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton’s former position in the Obama administration. The Secretary of State position entails power over approving cross-border pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure, as well as advancing the administration’s energy policy.11S.A. Miller. “Giuliani withdraws from consideration for Trump’s Cabinet,” The Washington Times, December 9, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/IQeSg 12“Presidential Permits for Border Crossings,” U.S. Department of State. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/slh9j 13“Bureau of Energy Resources,” U.S. Department of State. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/ebeRA

“Giuliani’s deep financial ties to the oil and gas industry are a major red flag; nominating him as Secretary of State would be another deeply disturbing move by President-elect Trump,” says League of Conservation Voters Senior Vice President of Government Affairs Tiernan Sittenfield.14“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016.

“Trump’s consideration of Rudy Giuliani for secretary of state, with all of his ties to the fossil fuel industry, is par for the disastrous course the President-elect is setting,” says Dani Heffernan, US Communication Coordinator at 350.org. “Giuliani isn’t an outright climate denier, but his deep loyalties to the fossil fuel industry pose a threat to international action against climate change and, ultimately, a livable future.”15“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016.

Politico reports that Giulani confirmed president-elect Trump had offered him two “Cabinet-level positions” in government, and that he had turned down the positions because he “didn’t want to do it.”16Madeline Conway. “Giuliani: I turned down two Cabinet offers,” Politico, December 13, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rgNvT

While he declined to name the positions, he did say that they were “very high” and did not include the top job at state. Giulani dismissed suggestions that his decisions had been based on inadequate loyalty by Trump: “As far as I’m concerned, he fulfilled whatever loyalty that entails,” Giuliani said, referencing the two other job offers he said he received. “I mean, it was my own decision not to do it, largely because of my personal life.”17Madeline Conway. “Giuliani: I turned down two Cabinet offers,” Politico, December 13, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rgNvT

Fossil Fuel Ties & Lobbying

When Rudy Giuliani joined Bracewell & Patterson in 2005, expanding the firm’s New York office, it already had the reputation of being the firm of choice for major energy companies. In 2007, the New York Times called Bracwell & Patterson “perhaps the nation’s most aggressive lobbyist for coal-fired power plants, heavy emitters of air pollutants and carbon dioxide,” arguing it was “central to rolling back environmental regulations in the Bush years,” such as provisions of the Clean Air Act.18Sara Randazzo. “Bracewell & Giuliani is Losing … Giuliani,” The Wall Street Journal, January 19, 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. 19“Giuliani joins law firm renowned for defending energy interests,” Grist, April 9, 2005. Archived December 11, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/1vVFa 20Russ Buettner. “Giuliani’s Tie to Texas Law Firm May Pose Risk,” The New York Times, May 2, 2007. Archived December 11, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/YO9u4 21Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

Legal Clients

Some of the firm’s largest legal clients have included Shell Oil, and Chevron/Texaco. Bracewell & Giuliani helped Shell acquire 618,000 acres of the Permian Basin in 2012 from the Chesapeake Energy Corporation—itself a major client, and one that gave the firm hundreds of thousands of dollars for lobbying work from 2011-2015.22(Press Release). “BRACEWELL REPRESENTS SHELL IN 1.2 MILLION-SQUARE-FOOT SHELL PLAZA LEASE, CULMINATING ITS RESTRUCTURING OF NORTH AMERICAN REAL ESTATE HOLDINGS,” Bracewell, December 21, 2011. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/HfCVe 23(Press Release). “BRACEWELL REPRESENTS CHEVRON IN 0 MILLION SALE OF NGL PIPELINE,” Bracewell, October 27, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/HfCVe 24“Shell Represented by Bracewell in .9 Billion Purchase of Chesapeake’s Permian Basin Assets,” KinneyRecruiting, September 18, 2012. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/OgfLg 25(Press Release). “BRACEWELL REPRESENTS CHESAPEAKE ENERGY CORPORATION IN .25 BILLION JOINT VENTURE,” Bracewell, April 11, 2012. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fxHj1

Chevron/Texaco is a multinational energy company that, according to Forbes, is the 28th biggest public company in the world and the United States’ second biggest oil and gas producer, worth $192 billion. Chevron was responsible for one spill that released more than 18 billion gallons of oil and other waste into the Ecuadorian Amazon—30 times larger than the 1989 Exxon Valdez spill.26“#28 Chevron,” Forbes, May 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fJ3BH 27“Chevron (CVX) Stock Price, Financials and News,” Fortune 500. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/nMCCT 28Claudia Garcia. “A slippery decision: Chevron oil pollution in Ecuador,” Dw.com, September 8, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/j3br6 29“CHEVRON CORPORATION, Plantiff, V. STEVEN DONZIGER, et al., Defendants” (PDF). Case No. 11 Civ. 069 (LAK). PDF retrieved from theamazonpost.com. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog.

Other notable fossil fuel clients included Saudi Arabia’s oil ministry (despite Giuliani’s rejection of a $10 million donation from a Saudi prince after the September 11 attacks), Citgo (Venezuela’s state-owned oil company, which spent more than $5 million since 2014 lobbying against U.S. sanctions), and Pacific Gas & Electric, California’s largest utility, which was found guilty of violating safety regulations prior to a pipeline explosion that killed eight people and destroyed 38 homes. Bracewell represented the company in the case.30“Giuliani rejects million from Saudi prince,” CNN.com, October 12, 2001. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/5E0pB 31Lachlan Markay. “State-Owned Venezuelan Oil Firms Spends Millions on U.S. Lobbying,” The Washington Free Beacon, June 6, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/MhD4p 32Associated Press. “Pacific Gas & Electric Convicted of Misleading Investigators After Pipeline Blast,” The Wall Street Journal, August 9, 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/OvrTq 33“U.S. Drops 2 Million Alternative Fines Act Allegation Against PG&E,” Lexology, August 2, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/VN4Yh

Lobbying Clients

According to public lobbying disclosures, Giuliani’s firms have a long history with the energy industry with clients like Arch Coal and Chesapeake Energy. Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen’s Energy Program said that “Bracewell & Giuliani was probably the most premier energy lobbying firm in the 2000s.”34“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016. 35Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

Bracewell & Giuliani also lobbied for 11 years for Southern Company, a company vehemently opposed to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan and once ranked “the United States’ most irresponsible utility.” The firm also lobbied for gas and coal power plant operator Dynegy, frequently criticized for it’s air-polluting power plants, for seven years. GenOn Energy, which has racked up thousands of violations of federal and state water laws over the years, retained the firm as lobbyists for the same amount of time.36Bob Sussman. “Southern Company’s Attack on the Clean Power Plan: Some Important Unanswered Questions,” The Brookings Institution, December 17, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/UXqHp 37“Leadership We Can Live Without” (PDF), Green America, May 24, 2011. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. 38“Dynegy Agrees to Reduce Pollution,” St. Louis Public Radio. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/7fACO 39Jody Barr. “Report: Hamilton County among most polluted in U.S.” Fox 19 Now, May 10, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rN5Mk

There is significant overlap between the firm and the Electric Reliability Coordinating Council, a coalition of energy companies which opposes environmental legislation. The group’s director, Scott Segal, is a partner at Bracewell & Giuliani.40“SCOTT H. SEGAL: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/8zdeL

Jeff Holmstead, who in 2010 was referred to by the ERCC as its counsel, is also a partner at the firm (though as this transcript of his Senate testimony shows, he hasn’t always disclosed this connection).41“Statement from ERCC Counsel Jeff Holmstead on the EPA’s GHG ‘Tailoring’ Rule,” Electric Reliability Coordinating Council, May 13, 2010. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/BhlhR 42“JEFFREY R. HOLMSTEAD: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rhV2U 43“Testimony of Jeffrey R. Holmstead before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works” (PDF), U.S. Senate Committee on Environment & Public Works, July 8, 2015. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog.

While the ERCC has not revealed its full member list, some of its members are known to be Duke Energy, Salt River Project, and Southern Company, though it has also done work for mining company Arch Coal. These all were or still are Bracewell & Giuliani clients. At the same time, the ERCC has not only been one of Bracewell & Giuliani’s oldest clients, starting with the firm in 2001, but one of its most lucrative, too, paying out more than $1 million a year to the firm since 2008, dwarfing every other client listed.44“Lobbyists for the ‘Electric Reliability Coordinating Council’ Attack Clean Air Rules on Behalf of Arch Coal,” Polluterwatch, May 24, 2012. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/TNHOk

Giuliani left Bracewell & Giuliani in January 2016, moving to Greenberg Traurig, another firm maintaining a range of connections to the fossil fuel industry, as well as the pharmaceutical industry, with clients including Peabody Energy, Bayer Corporation, Colorado Interstate Gas, FPL Energy, General Motors Corporation, Generic Pharmaceutical Association, Golden Queen Mining Company, Business Roundtable, and others.45Liz Moyer. “Rudolph Giuliani to Join Greenberg Traurig Law Firm.” The New York Times, January 19, 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rhAu3 46Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

The firm has a close relationship to oil and gas producer El Paso Corporation, which is owned by Kinder Morgan. Greenbert Traurig lobbied for two of the company’s subsidiaries, El Paso Electric and El Paso Pipeline Group, from 2005 through 2013.47“Kinder Morgan – El Paso transaction completed,” Kinder Morgan. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/WR9Ud

There is a revolving door between the two entities, with one of Greenberg Traurig’s attorneys becoming vice president, legal and chief compliance officer at El Paso Electric (then CEO) of El Paso Electric. El Paso Corporation’s senior counsel of 15 years moved to Greenberg Traurig in 2014. One of the firm’s lawyers, serving as the company’s general counsel for nearly a decade also rejoined Greenberg Traurig in 2013.48“El Paso Electric Appoints El Pasoan Mary Kipp as New President,” El Paso Electric, September 18, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/E69fk 49“Mary E. Kipp: Chief Executive Officer,” El Paso Electric. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/dZWXi 50(Press Release). “Greenberg Traurig Grows Global Energy and Infrastructure Practice, Adds Elizabeth B. Herdes in Denver,” gtlaw.com, April 21, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aeKjp 51Emily Atkin. “Greenberg Traurig Adds Former El Paso General Counsel,” Law360, October 2, 2013. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/xMo9w

Some of Bracewell & Giuliani’s notable lobbying clients are below. View the attached spreadsheet for additional details on Bracewell & Giuliani’s lobbying by year (.xlsx).52Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

- Air Liquide USA LLC

- Ameren Corp.

- American Chemistry Council

- Arch Coal

- BlueFire Ethanol, Inc.

- Burlington Northern Santa Fe Corporation

- Briggs & Stratton

- Calais LNG Project Company, LLC

- Calera Corporation

- Chase Power Development, LLC

- Chesapeake Energy Corporation

- Coalition for Energy Efficient Electric Tankless Water Heaters

- Cornell Companies

- Cross-Sound Cable Company, LLC

- CSX Transportation, Inc.

- DTE Energy Corporation

- Duke Energy Corporation

- Dynegy Inc.

- Edison Electric Institute

- ELECTRIC RELIABILITY COORDINATING COUNCIL

- Energy Future Holdings

- Energy Recovery Council (Formerly Known as INTEGRATED WASTE SERVICES ASSOCIATION)

- Envirofuels

- Environmental Working Group

- Exterran

- Fulcrum BioEnergy

- GAS PROCESSORS ASSOCIATION

- GenOn Energy (formerly known as GenOn (formerly known as Mirant))

- Great Plains Energy

- Helix Energy Solutions

- INI Power Systems, Inc.

- Inter-Power/AhlCon Partners, L.P. – Colver Power Project

- International Utility Efficiency Partnerships, Inc.

- Iogen Corporation

- Kinder Morgan, Inc.

- LYONDELLBASELL (formerly known as LYONDELL CHEMICAL COMPANY)

- MBDA Incorporated

- MDU RESOURCES GROUP

- MINORITY MINERAL-RIGHT OWNERS IN THE VALLES CALDERA NATIONAL PRESERVE

- Mirant

- National Petrochemical and Refiners Association (NPRA)

- News Corporation

- NOVA ENGINEERING

- Nustar Energy Corporation

- Otter Creek Energy Project

- PARKER DRILLING COMPANY

- Phoenix Coal Corporation

- Progress Energy

- Range Resources Corporation

- S&B Infrastructure, LTD.

- Salt River Project

- Shallow Water Energy Security Coalition

- SOUTHERN COMPANY

- SUPERIOR RENEWABLE ENERGY, LLC

- Syngenta Corp.

- Tesoro Refining Company

- The Mosaic Company

- Valero Energy Corp.

- WAYNE E. GLENN ASSOCIATES

- XCEL ENERGY

It isn’t clear what Giulini’s own personal involvement with many of these companies was. Giuliani himself has never registered as a lobbyist, and he’s not listed as an attorney in legal cases involving the companies. In 2006, Newsday reported that Giuliani personally sat down with Shell executives, part of his role of “solidifying existing relationships” with the firm. It’s also worth noting that when working for his private consulting firm, Giuliani Partners, the former mayor regularly did lobbying work for his clients without ever registering himself as such, possibly because he didn’t technically meet the threshold of salaried time spent communicating with officials.53Democratic National Committee Press Release. “DNC: Giuliani Offers Iowa Just Another Friend to Big Oil,” PR Newswire, July 19, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Achive.is URL: https://archive.is/KZrnH 54Michael Shnayerson. “A TALE OF TWO GIULIANIS,” Vanity Fair, January, 2008. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/QF53V

Tyson Slocum says whether or not Giuliani was directly involved with some of these companies is beside the point:

“It would be one thing if you had some minor role,” he says. “It’s another when one of the world’s largest lobbying groups renames itself after you.”55“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016.

Stance on Climate Change

2007

Talking about a potential Carbon Tax on CNBC:56“Rudy Giuliani’s Ideas for Dealing with Global Warming,” YouTube video uploaded by user The Heat Is On, March 27, 2007. Archived .mp4 on file at DeSmog.

“I don’t like taxes. I don’t know how to make that any clearer. I don’t like taxes. I generally think taxes are, given the level of taxation we have, and a lot of our states and in the country, inventing new ones is a very big mistake. Find other ways to do it.

If you want to deal with global warming, the way to deal with global warming is to develop these alternative technologies. Really get serious about energy independence, which we should probably have been serious about 30 years ago. We wouldn’t be in this situation where we have to send money to our enemies.”

“Get serous about why we haven’t licensed a new nuclear power plant in 30 years. Because people are afraid of nuclear power. […] Nobody’s died from nuclear power.” […]

“I look at wind and solar from the point of view of, can we store that energy? Right now it’s inconsistent energy. When the wind is blowing, you get energy. When it isn’t, you don’t. Is there a way to develop a technology that you can store it? Can you clean coal? Carbon sequestration: it can be done. Can we expand it?

The other benefit of looking at it this way, which I consider a pro-growth way, is we move ourselves towards energy independence then we also create an industry. A new industry in America. And with the growth of China and the growth of India, if we’re at the head of that industry we”re going to make a lot of money in China and we’re going to make a lot of money in india. We won’t just be buying things from them; they’ll be buying things from us.”

In the same interview, Giuliani discusses the Kyoto Protocol and global warming:

“It would move [jobs] to China and India and it would have no impact on global warming. Whatever your scientific conclusion about global warming, whether it’s man-made, or it isn’t or whatever, the reality is that if you don’t have restrictions on China and you don’t have restrictions on India, our contribution ultimately is going to be minor. We could put all these restrictions on ourselves and have just as much arguable global warming if China, India—some of these other countries that are going to be contributing a lot more to this don’t become part of some sort of system […]”

October 2007

Grist reports that while Giulani said “I do believe there’s global warming,” on the campaign trail, in a later speech on energy in the summer in Waterloo, Iowa, he had hardly a word about the environment. Instead, he focused on tapping domestic sources of energy, including coal, which is considered a major contributor to global warming.57Joseph Romm. “Rudy Giuliani’s stance on climate and energy,” Grist, October 19, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/SP28I

Key Quotes

December 13, 2016

Speaking of Exxonmobil CEO Rex Tillerson’s appointment as secretary of state:58“The Latest: Energy Dept. pushes back against Trump team,” KIRO7, December 13, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/YHuOh

“I’m okay with the choice. I think Donald Trump has selected somebody who knows the world and can advise him on the world.”

July 2016

Rudy Giulani applauded Donald Trump at the Republican National Convention59“Rudy Giuliani: What I did for New York City, Donald Trump ‘will do for America’,” CNBC News, July 18, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/CPm2O

“”It’s time to make America safe again. It’s time to make America one again […] What I did for New York, Donald Trump will do for America!”

“Donald Trump has said the first step in defeating our enemies is to identify them properly and see the connections between them,” Giuliani said. “To defeat Islamic extremist terrorism we must put them on defense. If they are at war against us ― which they have declared ― we must commit ourselves to unconditional victory against them.”

“This includes undoing one of the worst deals America ever made ― Obama’s Nuclear Agreement with Iran that will eventually let them become a nuclear power and put billions of dollars back into a country that the world’s biggest state sponsor of terrorism.”

September 2015

Speaking at the annual Shale Insight conference, Rudy Giulani argued the natural gas industry was “not being supported by the national government in the way that it should be.” He told the audience of industry members that many people were “irrationally afraid” of fracking, and the industry needed to launch “a national effort to explain how relatively safe this process was.”60Jon Hurdle. “Giuliani urges shale industry to fight ‘irrational’ public fear of fracking,” StateImpact Pennsylvania, September 16, 2016. Archived December 14, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/XyTMe

February 2015

“I do not believe, and I know this is a horrible thing to say, but I do not believe that the president [Barack Obama] loves America […] He doesn’t love you. And he doesn’t love me. He wasn’t brought up the way you were brought up and I was brought up, through love of this country.”61“Giuliani: Obama doesn’t love America,” Politico, February 16, 2015. Archived December 12, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/GPaCB

In response to criticism for the above statement, Giuliani said “Some people thought it was racist—I thought that was a joke, since he was brought up by a white mother… This isn’t racism. This is socialism or possibly anti-colonialism.”62“Giuliani: Obama Had a White Mother, So I’m Not a Racist,” The New York Times, February 20, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/3UcFu

September 2014

In 2014, he called on President Obama to fast-track applications to export natural gas as part of a foreign policy strategy:63“Giuliani pushes shale gas as a foreign policy solution” PowerSource, September 6, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fq0Jj

“You know how President Obama is looking at non-military options to solve things such as the invasion of the Ukraine by Russia? It would have been within our abilities to export a massive amount of natural gas […] which would then have an impact on the world price of natural gas and would deprive Putin of the only strength he has left in his economy.”

August 2007

“I was once in the coal business for a short period of time. I ran a company that had coal mines in Hazard, Ky., so we were able to share stories about the coal industry and some of the struggles it faces and the need for clean coal and carbon sequestration […]”

“[The U.S. would be] “better off if we could rely somewhat more on our coal reserves which are greater (in number) than the oil reserves in Saudi Arabia. “There’s a real opportunity here to expand our economy and take advantage of the global economy by selling energy independence to others. And as a matter of national security to put ourselves in a position where we don’t have to rely so much on oil from other parts of the world.”

“One of my 12 commitments to the American people is to make our country energy independent and coal plays a big role in that.”64Christian Giggenbach. “Giuliani touts importance of coal,” The Register-Herald, August 3, 2007. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/hNDTO

June 2007

“Energy independence: if we can make that a major focus of American policy for the next 5-10 years, is a great industry for us to sell to China and India. They need energy independence. We should be able to figure out how to produce it and then we can sell it to them.”65“Giuliani on energy independence,” YouTube video uploaded by user The Heat is On, June 18, 2007. Archived .mp4 on file at DeSmog.

Key Deeds

June 24, 2019

Nearly 100 internal documents were leaked to Axios in 2019. As Axios reported, the documents identified a host of “red flags” about many individuals who would go on to work in the Trump administration, as well as others who were considered but failed to secure a position.66“Full list: The leaked Trump transition vetting documents,” Axios, June 24, 2019. Archived June 24, 2019. Archive.is URL: http://archive.is/gm9i7

Giuliani was listed among the documents. Some notable samples from the internal documents below:

“The Houston-based law firm Giuliani joined as a named partner in 2005 lobbied in Texas for Citgo, the U.S. subsidiary of the Venezuelan state oil company then controlled by President Hugo Chavez, The New York Times reported in 2007.”

“Giuliani Promotes The Fact He Has Foreign Consulting Contracts, Including Ones With The Government Of Mexico And TransCanada, Of Keystone XL Fame.”

“In A Speech To Oklahoma State University In 2006, Giuliani Requested Travel On A ‘Private Gulfstream Jet That Cost The School $47,000 To Operate.’”

“Giuliani Was Hired By Purdue Pharma To Consult On OxyContin Security While He Was Under Contract With The DEA To Combat It.”

“Giuliani Partners Formed Strategic Alliance With Nextel While Consulting FCC On Crisis Communications.”67“Full list: The leaked Trump transition vetting documents,” Axios, June 24, 2019. Archived June 24, 2019. Archive.is URL: http://archive.is/gm9i7

October 2, 2016

Rudy Giuliani went on ABC News with George Stephanopoulos, discussing Trump’s taxes.68“’This Week’ Transcript: Rudy Giuliani and Sen. Bernie Sanders,” ABC News, October 2, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/oAROB

“My response is he’s a genius,” Giuliani began. “Absolute genius. I mean, the man in “The Art of the Deal” this is described. First of all, we’re talking about 26 years ago, perfectly legal. We should get that straight immediately. This is a perfectly legal application of the tax code. And he would’ve been fool not to take advantage of it. Not only that, he would’ve probably breached his fiduciary duty to his investors, to his business. You have an obligation when you run a business to maximize the profits. And if there is a tax law that says I can deduct this, you deduct it. If you fail to deduct it, people can sue you. Your investors can sue you.”

November 4, 2016

According to the Huffington Post, Rudy Giulani knew that the FBI planned to review emails tied to Hillary Clinton before the public announcement was released about the investigation, confirming that the agency had leaked information to Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.69Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

Giulani had already dropped several hints that he knew in advance that the FBI planned to look at the emails and had touted his connection to the FBI, mentioning that “outraged FBI agents” have told him they’re frustrated by how the Clinton investigation was handled.70Jim Dwyer. “As Trump Ally, Rudy Giuliani Boasts of Ties to F.B.I.” The New York Times, November 3, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/WX5fA

Two days before FBI Director James Comey announced that the agency was reviewing the emails, Giuliani said that Trump’s campaign had “a couple of surprises left.” He said on Fox News (October 22):

“I think he’s got a surprise or two that you’re going to hear about in the next few days. I mean, I’m talking about some pretty big surprise […] you’ll see. […] We’ve got a couple things up our sleeve that should turn this around.”71Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

Later, after the FBI re-launched their investigation of the emails, Giulani confirmed on “Fox & Friends” that he had heard about it from former FBI agents:72Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

“I did nothing to get it out, I had no role in it,” he said. “Did I hear about it? You’re darn right I heard about it, and I can’t even repeat the language that I heard from the former FBI agents.”

“I had expected this for the last, honestly, to tell you the truth, I thought it was going to be about three or four weeks ago, because way back in July this started, they kept getting stymied looking for subpoenas, looking for records,” he said.73Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

The Daily Beast‘s Wayne Barrett also explored Giulani’s FBI connections, reporting that Giulani’s ties to the agency dated back to his days as a U.S. attorney in the 1980s.74Wayne Barrett. “Meet Donald Trump’s Top FBI Fanboy,” The Daily Beast, November 2, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aBDf2

December 2, 2015

Rudy Giuliani appeared on “Your World With Neil Cavuto” to dispute President Obama’s statements linking climate change to terrorism (video below):75“Giuliani: Linking Climate Change to Terrorism ‘Like Saying Communism Was Caused by Climate Change’,” CNSnews.com, December 2, 2015. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/r9yNI

“The president’s wrong in linking somehow by fixing climate change if he’s gonna fix it, he’s gonna fix terrorism. That’s absurd. There’s no connection between the two things. Where it’s like two different things. It’s like saying I’m gonna fix terrorism by curing cancer,” Giuliani told Cavuto. ““The terrorism that we’re dealing with is not emerging from desperation. Many of these people are middle class or rich people who are involved in the terrorism. This is an ideologically or religiously based – and I would say certainly a misinterpretation of the religion and a, or if you want to call it a hijacking of the religion – but the religion has been turned into an ideology,” Giuliani said. “It’s like saying communism was caused by climate change.”76“Giuliani: Linking Climate Change to Terrorism ‘Like Saying Communism Was Caused by Climate Change’,” CNSnews.com, December 2, 2015. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/r9yNI

September, 2014

Rudy Giuliani spoke at the 5th Law of Shale Plays Conference in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The conference was presented by the Institute for Energy Law and the Energy and Mineral Law Foundation (EMLF).

Giuliani suggested Obama to fast-track applications to export natural gas as part of a foreign policy strategy:77“Giuliani pushes shale gas as a foreign policy solution” PowerSource, September 6, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fq0Jj

“You know how President Obama is looking at non-military options to solve things such as the invasion of the Ukraine by Russia? It would have been within our abilities to export a massive amount of natural gas […] which would then have an impact on the world price of natural gas and would deprive Putin of the only strength he has left in his economy.”

Giuliani also said that the energy industry should “massive campaign to educate the American people.” He added that “I would conduct this in the year 2015 — which is the lead-up to the 2016 presidential campaign — a very well thought-out, a very well-planned campaign throughout the United States. Maybe focus more in the key states where the presidential election will be battled out among the Democrats and Republicans to explain what this can do for us, what it can do for our economy.”78“Giuliani pushes shale gas as a foreign policy solution” PowerSource, September 6, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fq0Jj

Affiliations

- Greenberg Traurig — Senior Advisor to Greenberg Traurig’s Executive Chairman and as the Chair of the Cybersecurity, Privacy and Crisis Management Practice. Also Shareholder.79“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Greenberg Traurig. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/ZiHiA 80“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- Giuliani Partners — Chairman and Chief Executive Officer. *Note: The Giulini Partners’s website does not appear to be in operation, as of December 2016.81“Rudolph W. Giuliani: Chairman & Chief Executive Officer,” Giuliani Partners. Archived February 6, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/sYxuW

- Giuliani Security & Safety (GSS) — Leadership.82“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- Giuliani Capital Advisors — Acquired and later sold.83“Giuliani’s Investment Bank Is Sold,” The New York Times, March 5, 2007. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/W270t

- Bracewell & Giuliani (Now Bracewell)— Former Partner. Left firm in January, 2016.84“RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 13, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/N4Ci7 85(Press Release). “BRACEWELL ANNOUNCES THAT MAYOR RUDOLPH GIULIANI WILL LEAVE FIRM BY AMICABLE AGREEMENTMOVING ON TO OTHER CHALLENGES,” Bracewell, January 19, 2016. Archived December 12,2 016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/GciyE

- Patterson, Belknap, Webb and Tyler — (1977).86“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- White & Case — Former Partner.87“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- Anderson, Kill & Olick — Former Partner.88“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

Other Resources

- “Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Sourcewatch. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/ShnmQ

- “Rudy Giuliani,” Wikipedia. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/wvXVU

Image by Gage Skidmore [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons.

Resources

- 1“RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 13, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/N4Ci7

- 2“RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 13, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/N4Ci7

- 3“Rudolph W. Giuliani: Chairman & Chief Executive Officer,” Giuliani Partners. Archived February 6, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/sYxuW

- 4“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- 5“Giuliani Leaps Past 0,000 Mark in Big Oil Contributions,” Consumer Watchdog, October 19, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/Dh5Ju

- 6Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

- 7(Press Release). “BRACEWELL ANNOUNCES THAT MAYOR RUDOLPH GIULIANI WILL LEAVE FIRM BY AMICABLE AGREEMENTMOVING ON TO OTHER CHALLENGES,” Bracewell, January 19, 2016. Archived December 12,2 016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/GciyE

- 8“Giuliani’s Green Record,” Living on Earth, September 14, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/JZgFD

- 9“‘Meet the Press’ transcript for Dec. 9, 2007,” NBC News, December 9, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/NRbD3

- 10Christian Giggenbach. “Giuliani touts importance of coal,” The Register-Herald, August 3, 2007. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/hNDTO

- 11S.A. Miller. “Giuliani withdraws from consideration for Trump’s Cabinet,” The Washington Times, December 9, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/IQeSg

- 12“Presidential Permits for Border Crossings,” U.S. Department of State. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/slh9j

- 13“Bureau of Energy Resources,” U.S. Department of State. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/ebeRA

- 14“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016.

- 15“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016.

- 16Madeline Conway. “Giuliani: I turned down two Cabinet offers,” Politico, December 13, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rgNvT

- 17Madeline Conway. “Giuliani: I turned down two Cabinet offers,” Politico, December 13, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rgNvT

- 18Sara Randazzo. “Bracewell & Giuliani is Losing … Giuliani,” The Wall Street Journal, January 19, 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog.

- 19“Giuliani joins law firm renowned for defending energy interests,” Grist, April 9, 2005. Archived December 11, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/1vVFa

- 20Russ Buettner. “Giuliani’s Tie to Texas Law Firm May Pose Risk,” The New York Times, May 2, 2007. Archived December 11, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/YO9u4

- 21Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

- 22(Press Release). “BRACEWELL REPRESENTS SHELL IN 1.2 MILLION-SQUARE-FOOT SHELL PLAZA LEASE, CULMINATING ITS RESTRUCTURING OF NORTH AMERICAN REAL ESTATE HOLDINGS,” Bracewell, December 21, 2011. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/HfCVe

- 23(Press Release). “BRACEWELL REPRESENTS CHEVRON IN 0 MILLION SALE OF NGL PIPELINE,” Bracewell, October 27, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/HfCVe

- 24“Shell Represented by Bracewell in .9 Billion Purchase of Chesapeake’s Permian Basin Assets,” KinneyRecruiting, September 18, 2012. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/OgfLg

- 25(Press Release). “BRACEWELL REPRESENTS CHESAPEAKE ENERGY CORPORATION IN .25 BILLION JOINT VENTURE,” Bracewell, April 11, 2012. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fxHj1

- 26“#28 Chevron,” Forbes, May 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fJ3BH

- 27“Chevron (CVX) Stock Price, Financials and News,” Fortune 500. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/nMCCT

- 28Claudia Garcia. “A slippery decision: Chevron oil pollution in Ecuador,” Dw.com, September 8, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/j3br6

- 29“CHEVRON CORPORATION, Plantiff, V. STEVEN DONZIGER, et al., Defendants” (PDF). Case No. 11 Civ. 069 (LAK). PDF retrieved from theamazonpost.com. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog.

- 30“Giuliani rejects million from Saudi prince,” CNN.com, October 12, 2001. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/5E0pB

- 31Lachlan Markay. “State-Owned Venezuelan Oil Firms Spends Millions on U.S. Lobbying,” The Washington Free Beacon, June 6, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/MhD4p

- 32Associated Press. “Pacific Gas & Electric Convicted of Misleading Investigators After Pipeline Blast,” The Wall Street Journal, August 9, 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/OvrTq

- 33“U.S. Drops 2 Million Alternative Fines Act Allegation Against PG&E,” Lexology, August 2, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/VN4Yh

- 34“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016.

- 35Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

- 36Bob Sussman. “Southern Company’s Attack on the Clean Power Plan: Some Important Unanswered Questions,” The Brookings Institution, December 17, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/UXqHp

- 37“Leadership We Can Live Without” (PDF), Green America, May 24, 2011. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog.

- 38“Dynegy Agrees to Reduce Pollution,” St. Louis Public Radio. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/7fACO

- 39Jody Barr. “Report: Hamilton County among most polluted in U.S.” Fox 19 Now, May 10, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rN5Mk

- 40“SCOTT H. SEGAL: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/8zdeL

- 41“Statement from ERCC Counsel Jeff Holmstead on the EPA’s GHG ‘Tailoring’ Rule,” Electric Reliability Coordinating Council, May 13, 2010. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/BhlhR

- 42“JEFFREY R. HOLMSTEAD: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rhV2U

- 43“Testimony of Jeffrey R. Holmstead before the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works” (PDF), U.S. Senate Committee on Environment & Public Works, July 8, 2015. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog.

- 44“Lobbyists for the ‘Electric Reliability Coordinating Council’ Attack Clean Air Rules on Behalf of Arch Coal,” Polluterwatch, May 24, 2012. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/TNHOk

- 45Liz Moyer. “Rudolph Giuliani to Join Greenberg Traurig Law Firm.” The New York Times, January 19, 2016. Archived .pdf on file at DeSmog. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/rhAu3

- 46Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

- 47“Kinder Morgan – El Paso transaction completed,” Kinder Morgan. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/WR9Ud

- 48“El Paso Electric Appoints El Pasoan Mary Kipp as New President,” El Paso Electric, September 18, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/E69fk

- 49“Mary E. Kipp: Chief Executive Officer,” El Paso Electric. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/dZWXi

- 50(Press Release). “Greenberg Traurig Grows Global Energy and Infrastructure Practice, Adds Elizabeth B. Herdes in Denver,” gtlaw.com, April 21, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aeKjp

- 51Emily Atkin. “Greenberg Traurig Adds Former El Paso General Counsel,” Law360, October 2, 2013. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/xMo9w

- 52Lobbying Disclosures database. Search performed December 11, 2016.

- 53Democratic National Committee Press Release. “DNC: Giuliani Offers Iowa Just Another Friend to Big Oil,” PR Newswire, July 19, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Achive.is URL: https://archive.is/KZrnH

- 54Michael Shnayerson. “A TALE OF TWO GIULIANIS,” Vanity Fair, January, 2008. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/QF53V

- 55“Rudy Giuliani — And His Numerous Fossil Fuel Industry Connections — Out for Potential Post in Trump Admin,” DeSmog, December 10, 2016.

- 56“Rudy Giuliani’s Ideas for Dealing with Global Warming,” YouTube video uploaded by user The Heat Is On, March 27, 2007. Archived .mp4 on file at DeSmog.

- 57Joseph Romm. “Rudy Giuliani’s stance on climate and energy,” Grist, October 19, 2007. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/SP28I

- 58“The Latest: Energy Dept. pushes back against Trump team,” KIRO7, December 13, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/YHuOh

- 59“Rudy Giuliani: What I did for New York City, Donald Trump ‘will do for America’,” CNBC News, July 18, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/CPm2O

- 60Jon Hurdle. “Giuliani urges shale industry to fight ‘irrational’ public fear of fracking,” StateImpact Pennsylvania, September 16, 2016. Archived December 14, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/XyTMe

- 61“Giuliani: Obama doesn’t love America,” Politico, February 16, 2015. Archived December 12, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/GPaCB

- 62“Giuliani: Obama Had a White Mother, So I’m Not a Racist,” The New York Times, February 20, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/3UcFu

- 63“Giuliani pushes shale gas as a foreign policy solution” PowerSource, September 6, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fq0Jj

- 64Christian Giggenbach. “Giuliani touts importance of coal,” The Register-Herald, August 3, 2007. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/hNDTO

- 65“Giuliani on energy independence,” YouTube video uploaded by user The Heat is On, June 18, 2007. Archived .mp4 on file at DeSmog.

- 66“Full list: The leaked Trump transition vetting documents,” Axios, June 24, 2019. Archived June 24, 2019. Archive.is URL: http://archive.is/gm9i7

- 67“Full list: The leaked Trump transition vetting documents,” Axios, June 24, 2019. Archived June 24, 2019. Archive.is URL: http://archive.is/gm9i7

- 68“’This Week’ Transcript: Rudy Giuliani and Sen. Bernie Sanders,” ABC News, October 2, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/oAROB

- 69Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

- 70Jim Dwyer. “As Trump Ally, Rudy Giuliani Boasts of Ties to F.B.I.” The New York Times, November 3, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/WX5fA

- 71Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

- 72Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

- 73Mollie Reilly. “Rudy Giuliani Confirms FBI Insiders Leaked Information To The Trump Campaign,” The Huffington Post, November 4, 2016. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aMQx4

- 74Wayne Barrett. “Meet Donald Trump’s Top FBI Fanboy,” The Daily Beast, November 2, 2016. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/aBDf2

- 75“Giuliani: Linking Climate Change to Terrorism ‘Like Saying Communism Was Caused by Climate Change’,” CNSnews.com, December 2, 2015. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/r9yNI

- 76“Giuliani: Linking Climate Change to Terrorism ‘Like Saying Communism Was Caused by Climate Change’,” CNSnews.com, December 2, 2015. Archived December 13, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/r9yNI

- 77“Giuliani pushes shale gas as a foreign policy solution” PowerSource, September 6, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fq0Jj

- 78“Giuliani pushes shale gas as a foreign policy solution” PowerSource, September 6, 2014. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/fq0Jj

- 79“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Greenberg Traurig. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/ZiHiA

- 80“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- 81“Rudolph W. Giuliani: Chairman & Chief Executive Officer,” Giuliani Partners. Archived February 6, 2015. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/sYxuW

- 82“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- 83“Giuliani’s Investment Bank Is Sold,” The New York Times, March 5, 2007. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/W270t

- 84“RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI: PARTNER,” Bracewell. Archived December 13, 2014. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/N4Ci7

- 85(Press Release). “BRACEWELL ANNOUNCES THAT MAYOR RUDOLPH GIULIANI WILL LEAVE FIRM BY AMICABLE AGREEMENTMOVING ON TO OTHER CHALLENGES,” Bracewell, January 19, 2016. Archived December 12,2 016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/GciyE

- 86“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- 87“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy

- 88“Rudolph W. Giuliani,” Giuliani Security & Safety. Archived December 12, 2016. Archive.is URL: https://archive.is/4dCPy