Introduction

A growing body of research confirms that shale gas production, including the gas drilling method known as hydraulic fracturing (”fracking”), is a significant source of greenhouse gas pollution and a growing threat to human health and the environment. Far from being a “bridge fuel” towards a sustainable energy future, multiple reports reveal that methane leakage throughout the shale gas production lifecycle has produced dangerous levels of emissions, surpassing even coal in its climate disruption-causing potential. Despite this fact, and evidence that shale gas drilling has contaminated groundwater with cancer-causing agents, the federal government is on track to propel the gas industry to new heights by approving multiple liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals.

Current law dictates that LNG export terminals must face broad environmental and public interest review by the Department of Energy (DOE) and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). However, the Obama administration has pledged to hasten the regulatory process, while Congress has placed renewed pressure on regulators to streamline approvals. And LNG export applicants face lower regulatory barriers when exporting to countries that have free trade agreements with the United States.

Connecting U.S. natural gas to the global market through LNG exports will raise the price of natural gas for U.S. consumers and provide a powerful new market incentive for expanded domestic fracking. The climate and ecological consequences of such a pursuit are unquestionably dangerous. But most policymakers in Washington have ignored that element of the debate. Instead of conducting a sober analysis of the costs and benefits of expanding LNG exports, regulators and lawmakers have followed the lead of a multi-tentacled lobbying campaign managed by the shale gas industry.

Since 2012, the Obama Administration has approved four LNG export terminals: Sempra Energy’s Cameron LNG facility in Louisiana; Freeport LNG, which is co-owned by ConocoPhillips and located in Texas; Cheniere Energy’s Sabine Pass LNG terminal in Louisiana; and the Lusby, Maryland-based Cove Point LNG facility owned by Dominion Resources. The rhythmic quarter-by-quarter lobbying blitz by gas interests in Washington has placed great pressure on the Obama Administration to approve over a dozen more terminal applications currently under review.

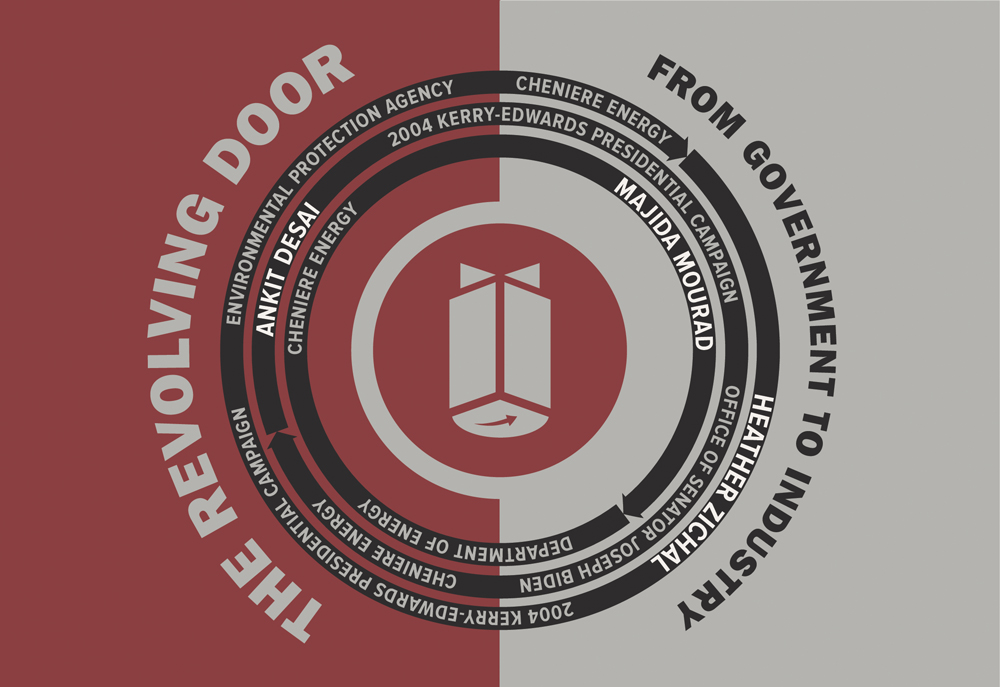

This report shines a light on the various ways the natural gas and LNG export lobby has come to dominate the political process, from buying access to the White House, federal agencies and Congress, to engaging in a forceful campaign to shift public opinion and distract from the dangers posed by unfettered shale gas exploration and production.