This report was produced as part of ivoh’s Restorative Narrative Fellowship.

On the evening of January 6, Louisiana state regulators issued 15 key permits to the Taiwanese petrochemical corporation Formosa for its $9.4 billion plastics manufacturing complex proposed for the historically black area of St. James Parish. Word spread today about the approvals, which pave the way for the project’s construction, opposed by local and national environmental advocates.

Sharon Lavigne, a demure, 67-year-old recently retired special-ed teacher born and raised in St. James Parish, cried when she heard the news. Her community along the Mississippi River is already saddled with petrochemical plants and oil storage tanks, which release known carcinogens into the air that she fears are making her and her family sick.

I spoke to Lavigne, who has tirelessly fought the project since the fall of 2018, just after news broke of the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality’s (LDEQ) decisions for Formosa.

“Something isn’t right about this,” said Lavigne, who founded the community group RISE St. James to oppose new industrial development in the area. After doing everything she could to raise awareness about why Formosa shouldn’t build its plastics plant in St. James, she is baffled by the state’s decision.

LDEQ’s reasons for approving the project have not been made public but are expected in the coming days.

Though the project still doesn’t have all the necessary permits, this week’s air permits help it clear a major hurdle.

However, Rise St. James and the Louisiana Bucket Brigade recently presented to the St. James Parish Council evidence of two suspected slave cemeteries on the former plantation property where the complex is proposed.

Sharon Lavigne at a protest in front of the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality on December 10, 2019. There, members of Rise St. James, the Louisiana Bucket Bridge, and the Center for Biological Diversity called on the state regulator to deny Formosa the air permits it granted this week.

On December 23*, Lavigne and members of RISE St. James asked the council to rescind the land use permit the parish’s planning commission granted on October 30, 2018 and let their relatives rest in peace. She hopes that this development could help sway politicians to stop the project’s growing momentum.

Evolution of an Environmental Justice Warrior

Lavigne has evolved from a soft-spoken, shy, concerned citizen to an environmental justice warrior to be reckoned with. She believes that she is answering God’s call to protect her neighborhood and save the planet.

“I’m David and I’m going up [against] a big ol’ Goliath — and I’m going to win,” Lavigne told me before this week’s decision. “It is a true story and it can happen again.” Lavigne has seemingly unflappable faith in the Bible and her church.

Lavigne’s Goliath in this case is Formosa. She is trying to stop the corporation from building a sprawling plastic manufacturing complex a mile and a half from her front door.

The air outside Lavigne’s home in Welcome, Louisiana, part of St. James Parish District 5, was already polluted before she learned that local politicians clandestinely changed a land use plan in 2014 from residential to residential/future industrial. That change made this district and the one across the river, with their existing pipelines and river access, even more desirable to major industry.

District 5’s population of about 5,000 is 86 percent African-American in an area equally steeped in impact from institutionalized racism and the growing climate crisis.

NuStar Energy oil tanks and train terminal in St. James, Louisiana, next to the community on Burton Lane where Lavigne’s friends, Mayho and Hunter lived, and close to where the Bayou Bridge pipeline terminates. Flight made possible by SouthWings.

St. James Parish is in the middle of an 80-mile stretch of the Mississippi River, from just outside of New Orleans up to Baton Rouge. It used to be known for its bucolic landscape lined with sugarcane fields, former slave plantations, and churches, but over the last 50 years, it has been transforming into an industrial wasteland.

That transformation is poised to worsen tenfold as more petrochemical companies build mega-plastic manufacturing plants, dwarfing the facilities already polluting the region known to industry as the Petrochemical Corridor, and to locals as Cancer Alley.

In its most recent National Air Toxics Assessment, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) identified sites along the river as hot spots for toxic chemical releases, including nearby St. John the Baptist Parish, where the risk of getting cancer from the polluted air is the highest in the country.

No official health survey has calculated the number of incidences of illness associated with toxic emissions from refineries and petrochemical plants that line the river in any of the communities. But just about everyone you speak to has cancer or has family members with cancer, and can point to houses nearby and tell you the names of members of each household who either have cancer or died of it.

A Flood of Climate Pollution and Impacts

From Lavigne’s yard, you can see the Mississippi River levee, which blocks her view of the river while protecting the area from flooding. Record-breaking rain in the Midwest that made its way downstream raised the river to a flood state for more than 200 days last year. It threatened to breach the levee, which held.

But the soundness of southern Louisiana’s flood protection system is questionable. Louisiana’s coastal wetlands’ land-loss rate is already more than a football field’s worth of land every hour. And in the latest National Climate Assessment report, federal scientists warned that impacts to the region, such as worsening floods, heat waves, and sea level rise, will intensify as the globe continues to warm.

So not only will any new petrochemical plants add toxic emissions to Lavigne’s air, but the plants themselves will be poised to wreak environmental destruction if there is a failure in the levee system or an extreme rain event swamps them.

New petrochemical plant operations will simultaneously bring us closer to the tipping point in the climate crisis that scientists are desperately warning about, because they will be fed by the United States’ glut of fracked natural gas, which is a major driver of global warming. The petrochemical and plastics industry accounts for about seven percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, the International Energy Agency reported in 2013.

All of that is why Lavigne is no longer the person sitting in the back row at community meetings at the Mt. Triumph Baptist Church. She is an outspoken opponent of all new plants coming into St. James and runs her own community group, RISE St. James. Now more often than not, she leads meetings and protests, at ease with a microphone, or a megaphone, in hand, demanding clean air. And not just in St. James, but also in New York City and Washington, D.C.

Sharon Lavigne shaking hands with House Majority Leader Steny Hoyer at the Congressional Convening on Environmental Justice, June 12, 2019.

“God is on my side,” Lavigne told me after finding out on September 5, 2019 that Wanhua Chemical, another plastic manufacturing giant she was also trying to stop, withdrew its land use request from a site across the river from her home.

After going to countless permit hearings and appeals hearings following St. James Parish’s granting of permits for both Formosa and Wanhau, she looked at Wanhua pulling out as a sign from God to fight on.

An Activist Is Born

It was just over a year ago on September 8, 2018 that Lavigne got her first taste of power while participating in a direct action. Close to 200 people marched in the Burton Lane neighborhood of St. James, close to the termination point of the recently installed 163-mile-long Bayou Bridge pipeline that stretches from West Texas across southern Louisiana.

Marching with her was a mix of concerned citizens and members of different environmental groups she had come to know over the previous year while trying unsuccessfully to stop the pipeline. Though they weren’t able to keep out the pipeline, the fight against it brought attention to the environmental injustice issues that Lavigne is desperate to call attention to.

Full of joy, Lavigne felt warmth in her heart as she marched with more than a hundred people past oil storage tanks that can leak volatile organic compounds including benzene, a known human carcinogen. The event gave Lavigne a sense of power. Now she wasn’t just standing up for her community, she was part of the environmental movement, and had allies willing to fight alongside her.

She and her brother, Milton Cayette, Jr., wore facemasks to make a point about the pollution. Cayette, a retired industry worker who lives nearby, led the way from his wheelchair.

Until recently, Cayette hadn’t connected the rise of industrial sites around him or his job working at a Shell chemical plant to cancer. His wife died of breast cancer a few years ago, and he has prostate cancer. Like his sister, he thinks it will be like a death sentence to remain in his house if more industrial plants are built nearby. Unlike Lavigne, though, he would take a buyout and move away, but a fair buyout isn’t on the horizon, so he loyally works alongside his sister fighting the proposed plants.

Lavigne with her brother, Milton Cayette, Jr. at his home in St. James.

The march took them by the house of Lavigne’s friend and close ally, Geraldine Mayho. Mayho, a retired custodial worker, desperately wanted to move away after learning that the pollution was impacting her health. Her doctor warned that her medical issues were related to chemical toxicity, and that leaving the area would be advisable.

Once during a visit to her home, Mayho showed me a letter from her doctor to make sure I believed her. She also showed me a couple of suitcases and boxes that she kept packed by her door in case she needed to get out fast or was able to find enough money to afford moving out.

The march also went by homes of some of the community’s most vulnerable residents, many senior citizens, handicapped and in poor health — some of the very people Lavigne feels compelled to protect with her activism. She and Mayho took me to meet some of them a couple months before the march. Each told me of their fear of being trapped if there were an accident or storm.

“During the march, I felt something inside me I never felt before,” Lavigne told me, “like something burst open and a black cloud lifted from over me.”

The marchers sang, “We shall overcome” and “Victory is Mine,” Lavigne’s favorite hymn, and chanted, “No justice, no peace.”

Lavigne carried a sign with a photo I took of Keith Hunter, who lived in the neighborhood and was a regular at community meetings. “Hunter would have been leading the march if he was still with us,” Lavigne told me. “He was all for the residents standing up and fighting back.” He died of a sudden respiratory illness in March 2018.

In addition to what Hunter and Mayho could see from their yards, in 2018 Yuhuang Chemical Inc., a Chinese chemical giant, began development of a $1.85 billion methanol facility just over three miles away.

At a rally following the march, Lavigne found the courage to take the microphone and tell her story in public for the first time. She told the group how she loved St. James, and how wrong it was that the government was allowing industry to poison the community. She spoke of how she was willing to fight for her children and grandchildren, who she wants to have clean air to breathe. Once she started reading the text she prepared, she overcame her trepidation of public speaking, and now never hesitates to tell her and her community’s story when given a chance.

Lavigne said that she thinks the area should be known as “Death Row” instead of “Cancer Alley” because residents are trapped in their homes. “We are waiting to be killed by cancer from all the pollution or by an explosion,” she said. “If there is an industrial accident, there is no way out for us.”

After that rally and march, Lavigne felt different. “The fight is in me,” she told me afterward. “I can’t explain the shift, but I knew I was ready to take the lead.”

Sharon Lavigne and other Coalition Against Death Alley (CADA) members approach the Sunshine Bridge in St. James Parish on June 1, 2019, during a protest march held CADA.

The Rise of RISE St. James

Lavigne was never involved in local politics. Her six children, her grandchildren, and her job and church kept her busy. But that changed after she went to a school board meeting in the fall of 2015 to support a friend who she felt was being unfairly fired. There, she met members of the organization H.E.L.P. (Humanitarian Enterprise of Loving People), who spoke about the pollution already plaguing the community.

She started going to H.E.L.P. meetings and became a member. There, she made the connection between industrial pollution and potential health impacts. And the more Lavigne learned about her situation, the more powerless she felt.

She learned that LDEQ, the state regulatory agency tasked to protect them from environmental pollution, wasn’t policing industry the way she always assumed it did. The agency relies heavily on industry self-reporting its own chemical emissions, and does not routinely test for leaks of the carcinogen benzene as well as other chemicals that can be harmful to inhale.

When companies do have a problem and alert LDEQ, the agency doesn’t notify surrounding residents about any pollution releases in real time, so they have no way of knowing if a release nearby might affect them.

“If you don’t look for a problem, you won’t find it,” said Wilma Subra, a chemist with the Louisiana Environmental Action Network (LEAN), an advocacy group based in Baton Rouge that has been working with community members in many Cancer Alley communities.

Sharon Lavigne speaking at an appeal hearing of a permit granted to Wanhua at the St. James Parish Council Meeting on July 24, 2019. Wanhua planned to build a $1.25 billion chemical complex in St. James Parish. Wanhua ended up withdrawing its application, citing changes in its project’s scope.

At the H.E.L.P. meetings, Lavigne learned that two petrochemical plants, Louisiana Methanol and Yuhuang Chemical, a subsidiary of Chinese chemical giant Shangdong Yuhuang Chemical Co., received permits to build petrochemical plants shortly after the local government changed the land use rules in 2014. Lavigne was infuriated that this happened without her knowledge. Had she known, she would have fought both.

After that, Lavigne started having trouble sleeping, and her moods fluctuated from depression to rage.

At a February 2017 H.E.L.P. meeting, Marylee Orr, the founder of LEAN, spoke to the group about possibly organizing buyouts for the community members who wanted to move because, with the coming influx of chemical plants, the prospect of worsening air quality was inevitable. She asked how many would be interested in moving if offered fair deals. Nearly everyone held up their hands — except Lavigne.

“Why should we have to leave?” she wondered. “We can stop them with God on our side.” And though she wasn’t alone in her desire to stay, she felt alone in her belief that, with God’s help, the community could stop more polluting industry from coming.

Lavigne credits her faith in God and her father’s role in the civil rights movement for inspiring her to stand up and fight back. She points to the legacy of Jim Crow laws that lingered in south Louisiana for the community’s lack of faith that they can stop Formosa.

Her father, Milton Cayette, Sr., was a sugarcane farmer, and her mother was a homemaker, always on hand to care for her and her five siblings. She describes her childhood as idyllic, spending much of her time outdoors playing with her siblings and the other kids in the neighborhood, fishing, picking blackberries, and going to church every Sunday.

But in her adolescence, her father’s activism and current events made her fearful. The assassinations of Martin Luther King, Jr. and John F. Kennedy robbed her of the sense of security, and made her worry about her father, who became the president of the local chapter of the NAACP.

Tired of waiting for St. James schools to integrate, he led the way for integration in St. James in 1966 by escorting seven African-American mothers and their children to the St. James High School, the same school that was recently purchased by Yuhuang Chemical for its methanol plant.

Afterward, she said, her father received death threats, his truck was set on fire, and his clients threatened to stop buying his crops, but he found other clients and persevered. “God has a plan for us,” Lavigne told me he would often remind her while she was growing up.

She speaks of him with pride and told me that sometimes she feels as if she is channeling him when speaking truth to power. Today it is Lavigne’s children who worry about her, because now she worries about receiving threats from industry supporters.

Sharon Lavigne next to her brother, Milton Cayette, Jr., a St. James resident, at Louisiana’s Department of Environmental Quality’s public permit hearing in Vacherie on July 9, 2019.

Though sometimes wistful that she won’t be able to kick back and enjoy her recent retirement, Lavigne believes she has no choice but to stay and fight. “I can’t imagine myself living anywhere else,” she told me. “My family is here, my church and community,” she said. “Everything is here.”

Lavigne’s property, which she shares with her family, is a 20-acre private oasis off Highway 18, which runs along the levee. Industrial developments have already taken a toll. Her fruit trees stopped producing fruit a few years ago, and though she can’t see the 10 existing petrochemical plants in District 5 or any of the numerous oil storage tanks from her yard, she can often smell their emissions. Despite the pollution, this place is still where she feels most at home, and she doesn’t want to leave. “Everything I know is in St. James,” she said. “I love my home and I’m too old to start over.”

In 2018, Lavigne learned at H.E.L.P. meetings that foreign-owned chemical plants were seeking permits to build in Districts 4 and 5, including Formosa’s plastics complex, developments that would greatly impact the quality of her life. Aside from added pollution, the truck traffic alone would destroy what little peace and quiet she still has left on her land.

She’d ask, “What can we do to stop them?” The group consensus — that the industrial plants couldn’t be stopped and that the best the community could hope for was a buyout — didn’t sit well with her.

That was when she started attending parish council meetings and permit hearings for additional plants seeking permission to build in St. James’ 4th and 5th districts.

She’d leave the meetings full of anger and disappear. She felt like the regulators and politicians weren’t listening as she and other St. James residents bared their hearts. If they really heard what the people were saying, then Lavigne reasoned, how could they be willing to continue selling out her community?

Not long after the 2018 march, Lavigne grew frustrated with some H.E.L.P. members’ attitudes that stopping the latest industrial development was impossible.

Sharon Lavigne, left, with Stephanie Cooper, the Vice President of RISE St. James, praying at a February 2, 2019 meeting held in St. James, where activists, lawyers, pastors, and residents opposing Formosa building near their homes met to plan how to stop the plant from being built.

Lavigne expressed her frustration to a cousin who encouraged her to start her own group. She toyed with the idea, but didn’t act until a few weeks later, when she had a conversation with God.

“I sat on my porch and read my Bible,” she said. “I saw the red birds.”

It is a rare thing to see red birds, she explained to me. Her daughter had told her red birds signify change. “I was so glad to see a red bird,” she said. “I prayed and I cried. Dear Lord, you gave me this land — this home — do you want me to leave?”

She asked him — and he said, “No,” she told me. “What do you want me to do?” she asked. “Fight” was the answer she got, and fight she has ever since.

Three weeks after the march, she settled on the name RISE St. James for her group, and invited members frustrated with H.E.L.P. to her home on October 3. She has been busy ever since. What started as a group of five concerned citizens is now about 20, with at least 100 supporters.

Sharon Lavigne at her house in St. James Parish, Louisiana, less than two miles from where Formosa plants to build a plastics and petrochemical facility.

Lavigne is determined to let people know what is happening to her small community.

She has been telling her story to anyone who will listen, speaking at various events. She thought that the more people knew about what is happening in St. James, the better her chance that LDEQ would reject Formosa’s air permits. And she wanted to make it impossible for politicians in a position to stop any of the proposed chemical plants to claim that they didn’t know the community opposed the projects, which the governor had already endorsed.

Lavigne is sick of being told by politicians that the chemical plants are welcome because they bring more jobs and tax revenue. Few in the local community are qualified to work in the proposed plant, and the companies have been given generous tax incentives — they are not paying the state revenues that would benefit her community. “Formosa plans to build a new park near my house,” she told me. “Like that makes it all right for them to build their plant.” No one is going to use a park close to the sprawling plastics facility if it is built, she contends. Already, she pointed out, sometimes people go outside, smell the bad air, and go back inside.

More Pollution Coming to a Land Rife with Environmental Racism

Meanwhile, Lavigne continues to show up at council meetings and hearings regarding all of the chemical plants trying to move in. She is also working with the Coalition Against Death Alley (CADA), a group that formed in early 2019 to fight environmental injustice in Cancer Alley. The coalition held two events involving days of marches last year to call attention to multiple issues related to environmental racism.

Lavigne with members of the Coalition Against Death Alley (CADA) on the steps of the State Capitol on June 3, 2019, at the end of a five day protest event.

Despite Wanhua’s retreat, stopping Formosa continues to be an uphill battle, especially with this week’s permit approvals.

The proposed plastics and chemical complex, Formosa’s Sunshine Project (named for its proximity to the Sunshine Bridge over the Mississippi) would be the largest of its kind.

The project was endorsed by Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards before the community even knew about it. He was the first to announce the project in an April 2018 press release welcoming Formosa to Louisiana, thanking the company for bringing needed jobs and revenue.

Sharon Lavigne holding plastic pellets, known as nurdles, from a Formosa plant found in Texas and delivered to Louisiana. The nurdles, used to make plastic goods and sometimes found polluting the environment, were collected by Diane Wilson and others near a Formosa plant in Point Comfort, Texas, that discharged the pellets into waterways. Wilson used the nurdles in a court case against Formosa that resulted in a $50 million settlement with the company.

Formosa’s project already has permission at the local level from the parish planning community and council, and received a Department of Natural Resources permit to operate in wetlands.

Lavigne and members of RISE showed up at every public meeting along the way, to make sure their objection was noted. She has pleaded with state regulators and politicians to put the people first, pointing out: “St. James is full.”

The fruits of Lavigne’s work were on display at the agency’s air quality permit hearing on June 14, 2019. More than 300 people turned up, and most of those speakers opposed the plant.

Many of Formosa’s opponents, including Lavigne, pleaded with the regulatory agency to say no due to the environmental racism of continually burdening communities of color with pollution. Separate findings by the EPA and the Union of Concerned Scientists have determined that communities of color already have higher exposure rates to air pollution than their white counterparts.

Last year, Lavigne went to Washington, D.C. to attend a Congressional Convening on Environmental Justice on June 26. There she learned the scope and history of environmental racism. Despite this history, the current administration is set on slashing the budget for the EPA’s environmental justice programs, while it rescinds rules to cut pollution from power plants and vehicles and boosts fossil fuel development.

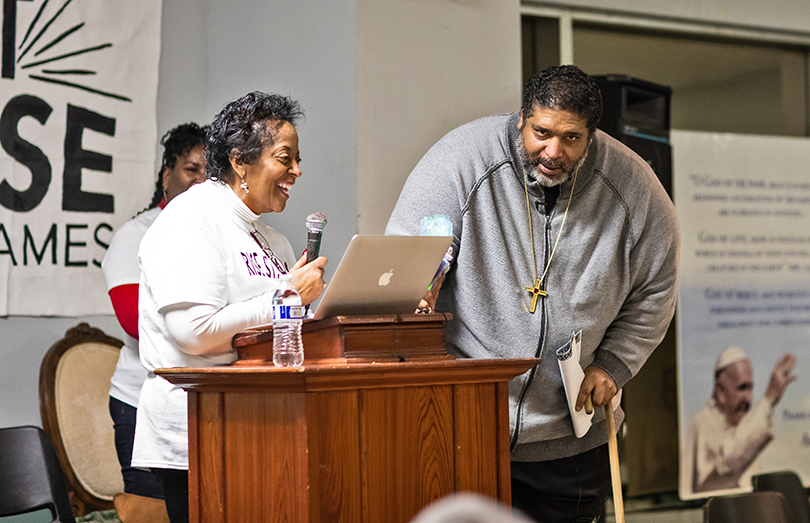

Lavigne with Rev. William Barber in St. James Parish on January 12, 2019.

Rev. William Barber, co-chair of the Poor People’s Campaign and a national leader in the civil rights movement, traveled to Louisiana in late June and met with Lavigne. She was pleased to be included on a panel he led in New Orleans, and to help lead a tour of Cancer Alley for his group the following day.

During the tour, it struck Barber that sites where slaves labored on plantations are now sites where petrochemical plants emit air pollution whose worst impacts affect nearby African-American populations. “So they went from plantations to plants, killing people with contamination,” Barber said.

The preacher vowed to include the plight of Cancer Alley residents in the Poor People’s Campaign platform, which is a modern revival of a project by Martin Luther King, Jr. Barber said he plans to challenge all of the Democratic presidential candidates to visit Cancer Alley, and stated that if they don’t, they have no business running for president.

Early the next morning, July 27, Geraldine Mayho died of complications from a stroke. On August 8, I attended her funeral, held at St. James Church, where Lavigne has been a lifelong member. The 200-year-old church is the largest structure for miles. It stands out in its opulence, behind row after row of oil storage tanks, some part of the nation’s strategic oil reserve.

Mayho’s family mixed with her newest friends, environmental activists easy to spot with their bright yellow RISE St. James T-shirts, stenciled with a likeness of Mayho and the text: “A true warrior gone home.”

Lavigne singing in the choir at her friend Geraldine Mayho’s funeral on August 7, 2019 at the St. James Catholic Church in St. James, Louisiana.

Lavigne spoke at the funeral, praising Mayho’s commitment to fighting against the chemical companies that want to come into their community. She laid a yellow rose on Mayho’s coffin before it was lowered into the ground. Across the street from the cemetery where Mayho was buried stand endless oil storage tanks. “I’m so sad that Geraldine never got to move,” Lavigne told me as we walked away.

Mayho’s death was a reminder to Lavigne of her own health issues. She told me that her blood sugar levels recently spiked, which she thinks is related to the stress that leading RISE St. James has added to her life. She recently had a cancer scare of her own, but she can’t see giving up, even after this week’s permit approvals for Formosa.

“If they think we are going to sit around and let them poison us, they are wrong,” Lavigne said. She is ready for the next round in the fight to stop the plastics complex. “God is on my side. He has sent me the people I need to help fight this fight, and that is what I’m going to do.”

A water tower in Welcome, Louisiana, near the site of Formosa’s planned plastics and petrochemical complex.

Updated 1/8/2020: This story has been updated to correct the date RISE St. James requested the parish council rescind Formosa’s land use permit. It was December 23, not 22.

Main image: Sharon Lavigne on her property in St. James, less than two miles from the proposed site of Formosa’s plastics manufacturing complex. Credit: All photos by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts