On February 15, 2018, a fracked natural gas well owned by ExxonMobil’s XTO Energy and located in southeast Ohio experienced a well blowout, causing it to gush the potent greenhouse gas methane for nearly three weeks. The obscure accident ultimately resulted in one of the biggest methane leaks in U.S. history. The New York Times reported in December that new satellite data revealed that this single gas well leaked more methane in 20 days than an entire year’s worth of methane released by the oil and gas industries in countries like Norway and France.

The cause of this massive leak was a failure of the gas well’s casing, or internal lining. Well casing failures represent yet another significant but not widely discussed technical problem for an unprofitable fracking industry.

Fracking and When Well Linings Fail

Casing failures occur when the steel or cement that’s lining an oil or gas well breaks or cracks, which means the well can’t maintain pressure anymore and creates a pathway for anything inside the well — such as fracking fluids — to leak into the surrounding environment. They can take place, as in the example of Exxon’s gas well in Ohio, at sites where hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, is happening.

The results of these failures can be catastrophic, as a 2017 paper published by the Society of Petroleum Engineers spells out: “Outcomes from casing failures include blowouts, pollution, injuries/fatalities, and loss of the well with associated costs.”

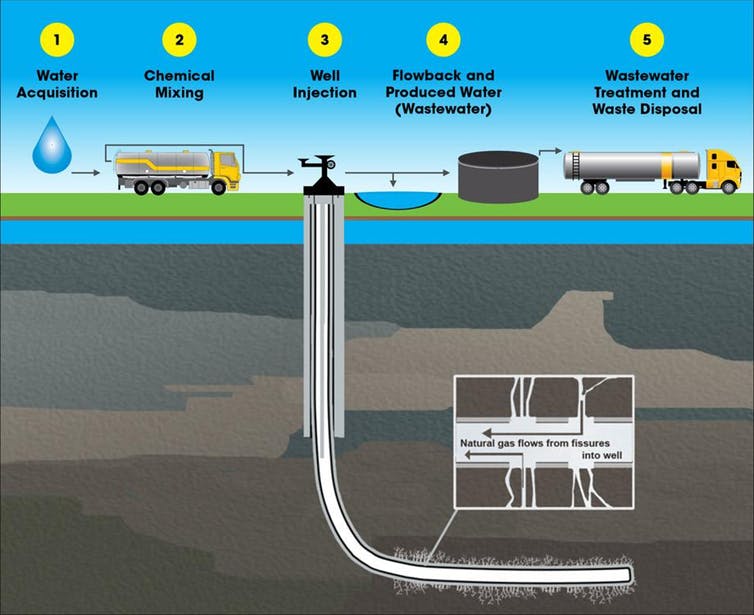

Wells used to produce oil and gas via fracking are different from what are known as “conventional,” or traditionally drilled, oil wells. While a fracked well is initially drilled vertically like a conventional well, at a certain point, the well bore turns and drills horizontally for distances up to 20,000 feet (that’s nearly four miles). The well’s vertical portion is made up of several layers of steel pipe casing and cement that are designed to protect nearby groundwater from the oil, gas, and fracking fluids that pass through the well.

The process of hydraulic fracturing is what releases the oil and gas from the shale. This is accomplished by pumping a mixture of water, chemicals, and sand under such high pressure that it breaks apart the rock, creating fractures that allow trapped oil and gas to flow up the well to the surface.

Representation of a horizontally drilled and hydraulically fractured natural gas well, with the cycle of water involved. Credit: Environmental Protection Agency, public domain

According to the Society of Petroleum Engineers paper, produced by petroleum engineer Neal Adams and others, casing failures have been linked to the stresses and high pressures required to complete the fracking process and the industry is grappling with this costly and hazardous problem. This paper identified the problem in depth and used strong language (for engineers), noting, “Incidents of casing failures occurring during fracture stimulation operations are increasing at an alarming rate.”

For an industry laser-focused on cutting costs, the risk of losing an entire fracking well gets its attention.

The Society of Petroleum Engineers itself will be discussing this issue at its February 6 meeting in Texas during a three-hour panel called ”Casing Deformation in Unconventionals: Case Histories, Root-Causes, Managing and Mitigating.” This is not some fringe issue for independent operators. The panel tackling this issue is made up of representatives from the major industry players, including Shell, BP, and XTO, the subsidiary of ExxonMobil that operated the blown well in Ohio.

This growing problem for the fracking industry can be traced to the same issues that have caused past failures: cutting corners on costs because shale companies have been losing money and are pushing the limits of technology to try to finally turn a profit and pay back their sizable debts.

Once again, this cost-cutting approach hasn’t been working, and the risks to the climate, the environment, and investors continue to mount.

More Stress Put to the Test

When DeSmog approached Dr. Anthony Ingraffea, Professor of Engineering Emeritus at Cornell University, about the issue of well casing failures, his response was simple. “It isn’t surprising,” he said.

Shale companies have continually promised investors that technology would be the solution to the ongoing financial losses for the industry. A few of the technological advances touted as the key to their financial troubles include drilling longer wells, pumping in more frac sand as proppant to keep the fractured shale pathways open, injecting more water, performing many more fracs per well, cramming in more wells per well pad with cube development, and optimizing operations with artificial intelligence.

New #fracking techniques: Longer laterals (44% longer), more water (250% more), more frac sand, and closer spacing of wells, have not significantly increased the recoverable resource. They are frontloading production, booming faster and busting faster. https://t.co/WDLdBmGUiY

— TXsharon (@TXsharon) May 12, 2019

The increasing pressures used to fracture the shale and number of frac hits in oil and gas wells may be contributing to the increasing problem of well casing failures, according to Dr. Arash Dahi-Taleghan, Associate Professor of Petroleum and Natural Gas Engineering at Pennsylvania State University.

“Nowadays, the problem is that they are not making only four or five fractures,” Dahi-Taleghan recently explained to the Journal of Petroleum Technology. “Sometimes, you have 150–200 fractures that are closely spaced together and the injections rates are high.” He also noted new techologies which use increased pressures and concluded that, “All of these things can put too much stress on the casing, as was not the case before.”

And that makes sense to a civil engineer like Ingraffea. Longer wells require higher pressure to blast the fracking fluids greater distances to fracture the shale along the length of the lateral, or horizontal portion of the well. That places greater stress on the whole well structure, he told DeSmog.

“You’re putting higher and different kinds of stress on the casing, and you are also subjecting the casing to many more repeated loadings because as you increase the lateral, you are going from five fracs to hundreds of fracs in some cases,” Ingraffea explained to DeSmog. “It all makes sense,” Ingraffea added about the increase in well casing failures.

Fracked oil and gas wells are built out of steel and cement, but they aren’t invincible. When these materials are repeatedly stressed during fracking operations, failures are bound to happen.

Cost Savings on Well Materials Lead to Well Failures

The recent Journal of Petroleum Technology (JPT) article quoting Dahi-Taleghan asks a question that should frighten shale investors: “An Unconventional Challenge: Can Casing Failures During Hydraulic Fracturing Be Stopped?”

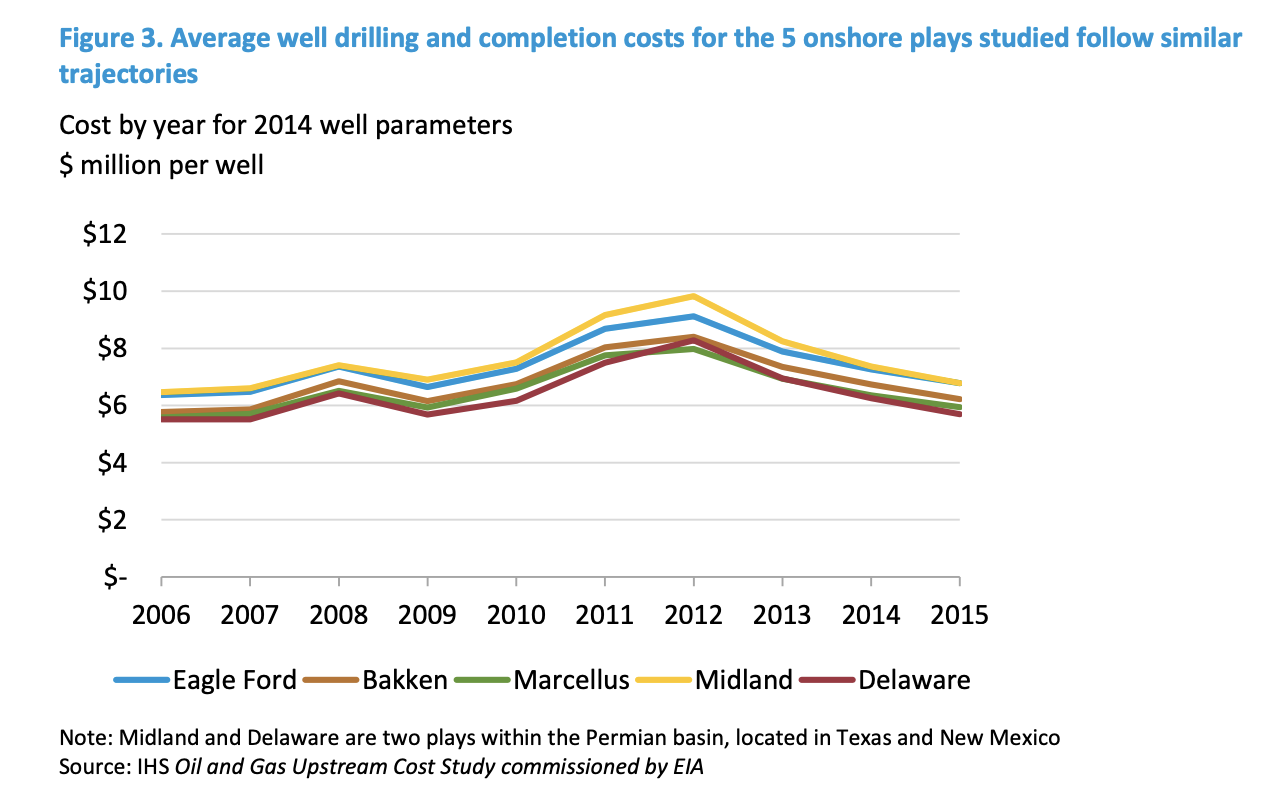

Drilling and fracking the new, longer wells can cost well over $10 million, a significant increase in cost from the shorter wells historically used by the industry. A 2016 report from the Energy Information Adminstration estimated historical well costs in the range of $6–10 million. Shale gas company CNX reported that recent wells cost $14 million, but the company hopes to reduce that cost to $12.5 million per well.

A well casing failure can turn that sizable investment into a total loss, which, depending on the situation, also may require even more money for cleanup. If casing failures can’t be stopped, the industry has a huge problem, which is certainly why this will be a major topic of conversation next month among petroleum engineers in Texas.

Average well costs for fracking industry 2005-2016. Credit: Trends in U.S. Oil and Natural Gas Upstream Costs, Energy Information Administration

Can casing failures be stopped altogether? That’s highly unlikely with these complex systems enduring extreme stresses. But these failures can be greatly reduced if the operators invest in the well structures.

“Casing is around 20 percent to 30 percent of the total well cost — that’s a huge amount of money, and because of constant budgeting issues, operators are choosing to pay the minimum cost of designing any well,” Christine Noshi, a petroleum engineer whose research focused on well casing integrity, told JPT.

George King, who JPT describes as “an independent consultant and leading technical voice on hydraulic fracturing,” has assessed the problem and his take is grim.

“The more that you try to skimp by on your pipe design, your cement, your couplings — that type of thing — the higher the risk that well is going to fail before you can get a return,” King explained to JPT. “That’s going to change your net present value calculations.”

King estimates “that in certain U.S. shale and tight oil fields, between 20 percent and 30 percent of horizontal wells are impacted to some degree.”

For shale companies already hemorrhaging money while betting on longer wells with many more fracs per well, that is exceptionally bad news.

After consistently losing money for the past decade, the shale industry has proven it can’t make money drilling shorter wells and has made a big bet on these much longer wells. But it still isn’t working.

Environmental and Climate Risks

Well casing failures pose a huge risk for water contamination via fracking fluids, which contain a vast mixture of chemicals with various health risks. And these failures represent another way that oil and gas production can lead to releases of the powerful greenhouse gas methane.

According to Adams’ 2017 paper in the Society of Petroleum Engineers, “Most observed failures have occurred in the shallow, uncemented sections of the hole,” which is pretty much the worst-case scenario from an environmental standpoint. Without cement to help contain the failing well, and especially at shallow depths, fracking fluids can blast through the internal lining and easily lead to groundwater contamination.

If uncemented sections are more likely to fail, why doesn’t the industry cement the full length of the well bore? Because many states don’t require it, and using more cement adds higher costs to an already expensive process that producers are desperate to contain. Cement doesn’t only provide a potential barrier between what’s going on inside the well and the surrounding environment, but as Ingraffea explained to DeSmog, it provides more structural integrity to help the well withstand the extreme forces of the fracking process, which can reach pressures up to 15,000 pounds per square inch.

The worst-case scenario for failure can be a well blowout, which is a financial disaster for the operator and can result in large methane leaks, as Exxon saw with its well blowout in Ohio. Exxon’s investigation concluded that high pressure was the culprit behind the failed well casing.

“The first satellite designed to continuously monitor the planet for methane leaks made a startling discovery last year: A little known gas-well accident at an Ohio fracking site was in fact one of the largest methane leaks ever recorded in the U.S.”https://t.co/pa2BUuPTaX

— Alexander Kaufman (@AlexCKaufman) December 16, 2019

Adams’ paper specifically notes that casing failures can result in well blowouts and includes the following troubling statement:

“As the results of this study have shown, most failures occur in the vertical section of the well above the top of cement. Failures observed in this section tend to be closer to the surface than the top of cement. Currently existing blowout control techniques are not immediately applicable in these cases.”

It took Exxon 20 days to cap the blown well in Ohio.

Casing Failure in Pennsylvania

A year ago, shale gas producer CNX experienced a well casing failure that resulted in a blowout in Pennsylvania.

In February, the state Department of Environmental Protection issued a notice of violation to CNX, citing the company for “failure to construct and operate a well to ensure that the well integrity is maintained” and “failure to equip the well with casings of sufficient strength.” However, the state did not fine CNX for the violations.

The well was plugged and filled with cement, representing a major loss for CNX, with the company reporting wells costing $14 million each. While the company doesn’t have plans to frack the other three wells it drilled on the same well pad – constructed with the same pipe that failed — it maintains that is an option in the future if an additional liner is added to the wells.

The Failure of the Great Fracking Experiment

The Society of Petroleum Engineers is meeting in Texas next month to discuss the problem of well casing failures, long after engineers should have figured out this problem. However, this has been the approach of the oil and gas industry over the course of hydraulic fracturing’s recent history.

This has been true with fracking industry-induced earthquakes. Water contamination. Methane emissions. Radioactive fracking waste. Child wells. Frac hits and moving dangerous fracked oil by rail.

And now, well casing failures. It’s worth noting that for many of these issues, the first response by oil and gas industry promoters has been to deny that there is a problem, thus delaying the identification and implementation of solutions and putting the public, environment, and climate at risk.

In 2014, Energy in Depth, a public relations effort by the Independent Petroleum Association of America and FTI Consulting, wrote that a “frequently repeated claim out of the anti-fracking camp” was that well casing failures were causing water contamination and then went on to cite the Society of Petroleum Engineers in explaining why these failures were so rare. Energy in Depth might want to touch base with those engineers again for a 2020 update.

Whatever the industry talking points (or in some cases, straight up denial), these costly issues continue to mount for the fracking industry at the same time when shale companies are facing the likelihood that most of the best oil and gas–producing acreage has already been drilled. If that turns out to be the case, paying back the high costs of drilling and fracking will become even more challenging for shale companies as new wells produce less oil and gas.

The fracking experiment has been a financial disaster. It has been a climate disaster. And it has contaminated large swaths of water and soil in places like North Dakota and is draining (and contaminating) much-needed freshwater supplies in arid regions. It has been potentially linked to rare cancers in youth in Pennsylvania. Additionally, the industry is trucking radioactive wastewater across the country with little in the way of protections.

And companies don’t have the money to clean up and shut down the hundreds of thousands of wells once they’re pumped dry, setting up the American public to foot that bill — or leave the problem to fester.

#Shale bear Mark Papa predicts just 400K production growth for US this year. Tells room at #IPTC2020 that OPEC oil will only become more important over next decade. “A change is coming.” Says capital starvation playing a role—BUT bigger role is resource depletion. #oilandgas pic.twitter.com/CZ76RGu90U

— Trent Jacobs (@TrentPJacobs) January 13, 2020

How should we expect the fracking industry to approach the growing problem of well casing failures? Just look to its track record, and don’t expect any surprises.

Main image: Footage of Powhatan Point XTO well pad explosion. Credit: Ohio State Highway Patrol via FrakTracker Videos

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts