In mid-January, Adam Waterous, who operates the private equity firm Waterous Energy Fund, made a prediction about the crown jewel of the U.S. shale oil industry, the Permian shale play that straddles Texas and New Mexico.

“We think we are at or near peak Permian,” Waterous told Bloomberg. “The North American oil market has been grossly overcapitalized, which is not sustainable.”

Bloomberg reporter Simon Casey goes on to qualify that “[p]redicting peak Permian output for 2020 isn’t a mainstream view.” However, evidence is piling up that the U.S. shale industry may indeed be close to peaking as it runs out of the two things required to continue increasing oil production: money and what’s known as “tier one acreage.”

Tier one acreage is the term for the areas that produce the most oil per well. It’s also known as “sweet spots,” “core acreage,” or “good rock.”

The idea of the U.S. shale revolution peaking long before either the broader oil and gas industry or the Energy Information Administration expects isn’t a popular one. And the idea was even less popular when DeSmog started detailing why it was likely all the way back in October 2018, and even when the Wall Street Journal made the case a year later.

Today, as more and more Permian oil companies go bankrupt and wells in the nation’s most prolific oil patch turn out less and less, one early warning nows seems especially prescient. In 2018, Paal Kibsgaard, the CEO of Schlumberger — one of the largest oil services providers — cautioned about declining well productivity in the Permian Basin, pointing to increasing “child wells” and to the boom-gone-bust Texas oilfield, the Eagle Ford Shale.

“We are already starting to see a similar reduction in unit well productivity to that already seen in the Eagle Ford, suggesting that the Permian growth potential could be lower than earlier expected,” warned Kibsgaard, who was replaced as CEO in 2019.

Another warning from a former Schlumberger executive noted that Permian performance results were misleading, because satellite data had revealed that a thousand wells that had been fracked had not been reported, skewing the basin’s overall performance to look better than it is.

Schlumberger lost $10 billion in 2019 and laid off 1,400 U.S. workers, making Kibsgaard seem smart to be worried the year prior. The company has also cut in half the amount of fracking equipment it will have available. That is not a sign of optimism for the future of U.S. fracking or its crown jewel, the Permian.

BIG OIL EARNINGS SEASON: Pretty weak set of results by both Exxon Mobil and Chevron, dragged down by low prices and downstream margins (and for XOM, chemicals). More ominous, the Permian appears to be slowing down (at least, on XOM slide; CVX didn’t provide a Permian chart) #OOTT pic.twitter.com/S3KdAYlNlZ

— Javier Blas (@JavierBlas) January 31, 2020

The End the Era of Being ‘Grossly Overcapitalized’

As DeSmog has detailed, the fracking industry has lost hundreds of billions of dollars and now is saddled with debts it will never be able to pay back because the best days of U.S. shale oil production appear to be in the past.

The flow of low interest loans to shale oil and gas companies has dried up, signaling the end of the era of being “grossly overcapitalized.”

And while there is still much debate about how much oil the Permian can yet produce, there is little debate anymore about the fact that investors are no longer eager or willing to loan companies money to frack — unless the companies can prove to be profitable — which is something the majority of them have failed to do.

Last week, investment website Seeking Alpha highlighted Abraxas Petroleum, a Texas-based company with Permian assets, describing the company’s “flawless history of producing negative free cash flow” — a brutal way of saying the company has never made a profit, like many of its peers.

But Abraxas has produced oil and gas in an era when the industry was “grossly overcapitalized,” which enabled the company to continue borrowing more money to keep drilling. But those days are over and companies like Abraxas can’t continue to exist without investors somewhere giving them more money to keep up a very expensive production process. Seeking Alpha speculated that a possible Chapter 11 bankruptcy may be in the fracker’s future.

The whole situation was summed up well in a recent article from Barron’s:

“Equity infusions have dried up, and lenders are getting picky. They insist that borrowers actually demonstrate cash flow and sustainability, qualities evinced by a shrinking number of shale producers. And starting in 2020, these companies face a wall of debt totaling $71 billion and maturing over the next seven years, according to research and analytics provider Rystad Energy.”

The industry as a whole is facing huge amounts of debt and the only way to pay it back is by making money selling oil and gas, something the industry has failed to do even at much higher prices.

Low oil prices combined with negative natural gas prices in the Permian, plus the end of easy access to investors, is not a formula for Permian success. While there is ample evidence that shale CEOs have no problem losing other people’s money as long as they are getting paid, expect a lot fewer opportunities for that type of work in the Permian going forward. But don’t think that that strategy will stop before all the remaining cash in the industry has dried up.

It’s possible that the industry has reached peak debt, and thus, peak production is likely to follow.

The Rocks Don’t Care If CEOs Promise Oil

Even if the shale industry had made money the past decade and was sitting on a pile of cash, it would still have another serious problem: It’s running out of tier one acreage. Money pays for drilling, fracking, and CEO bonuses, but it can’t make oil appear where there isn’t any.

In 2018, Mark Papa, then-CEO of shale company Centennial Resource Development, was already warning of the lack of tier one acreage.

“There are good geological spots in shale plays and weaker geological spots, and a lot of the good geological spots have already been drilled,” Papa explained during a panel discussion at the industry conference CERAweek.

Papa is now the chairman of Schlumberger and made another prediction about U.S. shale production at an industry conference this past January. Trent Jacobs of the Journal of Petroleum Engineering live-tweeted Papa’s comments, which include the warning: “A change is coming.”

#Shale bear Mark Papa predicts just 400K production growth for US this year. Tells room at #IPTC2020 that OPEC oil will only become more important over next decade. “A change is coming.” Says capital starvation playing a role—BUT bigger role is resource depletion. #oilandgas pic.twitter.com/CZ76RGu90U

— Trent Jacobs (@TrentPJacobs) January 13, 2020

And even though the industry is in serious financial trouble, Papa says resource depletion is the bigger issue. Even if investors were foolish enough to continue to loan money to the shale industry, the oil isn’t there to pay back the loans, much less make a profit. “Starvation” and “depletion” are not words used to describe a boom. Will the industry listen to Schlumberger’s warnings in 2020 after ignoring them in 2018?

Jacobs also reported that Papa believes two other large shale basins — the Bakken in North Dakota and Eagle Ford in Texas — have already peaked.

This week, the Journal of Petroleum Technology (JPT) highlighted how quickly shale well production declines and the news isn’t good for the Permian’s prospects. JPT noted that new data reveals a flaw in “[on]e of the key assumptions that justified the long-term economics” of shale wells.

To put it simply, the oil companies promised investors 30 years of oil production, but in reality, the wells dry up much faster than that.

Evidence is building that CEOs promised an amount of Permian oil that very likely isn’t there.

The Shale Boom Is Becoming a Bust

As DeSmog reported last December, the energy analysts at Wood Mackenzie have a very good track record of early and accurate predictions about the shale oil industry. In a webinar on decline relates of Permian oil wells, Wood Mackenzie research director Ben Shattuck outlined a potential future for the oil patch’s well producion.

“We’re transitioning to a point in time, where the investment community was enamored of the next well and how big it might be,” Shattuck said. “That has changed for a variety of reasons. One very important reason is the next well might not be bigger. It might be smaller.”

That is one very important reason. And it comes down to geology, the end of tier one acreage, and the industry trying to produce more oil by packing in more wells closer to each other (“child wells” that surround a “parent well”). All of which results in an oil field beginning to peak in production and then decline.

To be clear, the Permian has not yet peaked. And because companies like Exxon and Chevron are now major players in the region and still have access to the money required for oil production — unlike many other producers — those companies will continue to increase production even if it isn’t profitable. However, both of those companies just delivered disappointing financial results, meaning even that scenario can’t go on forever.

The lack of remaining tier one acreage is something that even Exxon and Chevron can’t change.

The math is simple. If each new well drilled produces less than the earlier, and unprofitable, wells, then the peak is quickly approaching.

“I’m done with fossil fuels. They’re done,” @MadMoneyOnCNBC‘s @JimCramer says after oil giants Exxon Mobil and Chevron reported Q4 earnings this morning. “We’re in the death knell phase.” https://t.co/rdcmoeRGMB pic.twitter.com/yl8iP7hpMi

— CNBC (@CNBC) January 31, 2020

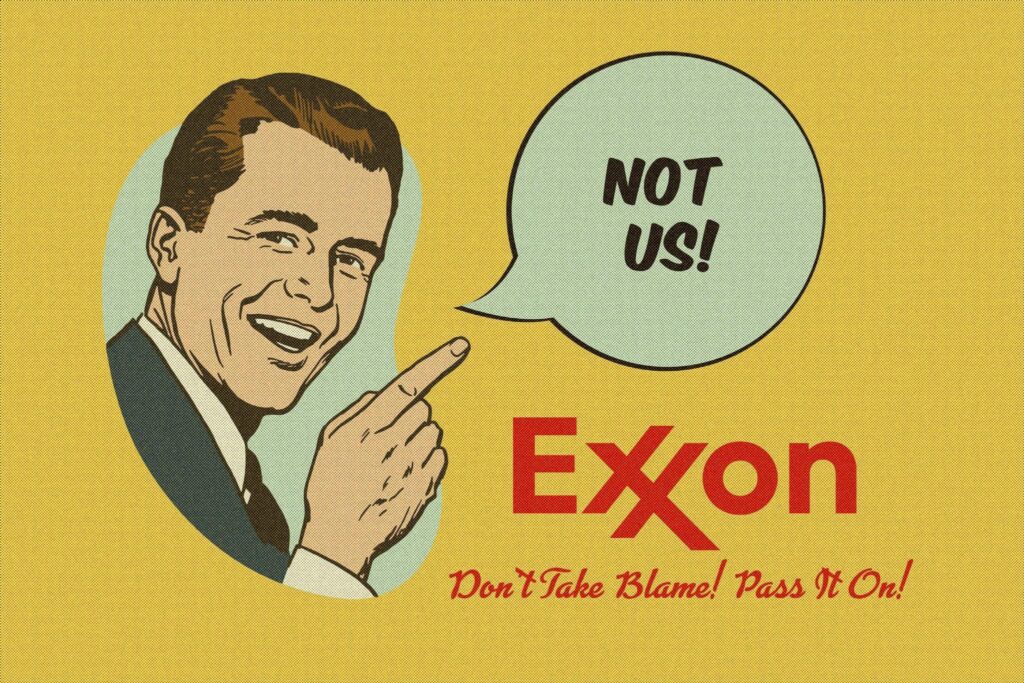

Main image: Advertisement noting oil field declines that is posted in the George Bush Intercontinental/Houston Airport. Credit: Justin Mikulka, DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts