A large fire at ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge oil refinery late on February 11 lit up the sky for miles and continued until dawn. The night of the fire, ExxonMobil representatives claimed that air monitoring inside the plant and in surrounding neighborhoods did not detect the release of harmful concentrations of chemicals, a claim echoed by first responders and state regulators. What unfolded, however, reinforced a growing community movement to require real-time independent air pollution monitoring at industrial facilities.

A week after the incident, Exxon filed a required “seven-day report” to the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ) indicating the plant released four toxic chemicals during the incident, including benzene, butadiene, and sulfuric acid in quantities above allowable limits, and sulfur dioxide. Exxon said in its report that thousands of pounds of unspecified flammable vapor released in the incident were burned off by the fire and that little, if any, escaped the refinery in concentrations that could have posed a risk to nearby residents.

However, many in the community were outraged about how much time passed before they were notified of potential hazards and expressed doubt that the fire had no significant effect on the air quality around the plant.

The incident reignited calls from environmental advocates for more real-time monitoring of a class of potentially toxic chemicals known as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) at chemical plants and refineries. They say that with this kind of publicly available monitoring, residents near such facilities won’t have to rely on industry for health warnings in case of an emergency.

Senator Cleo Fields leading a community meeting in Baton Rouge on February 19, 2020.

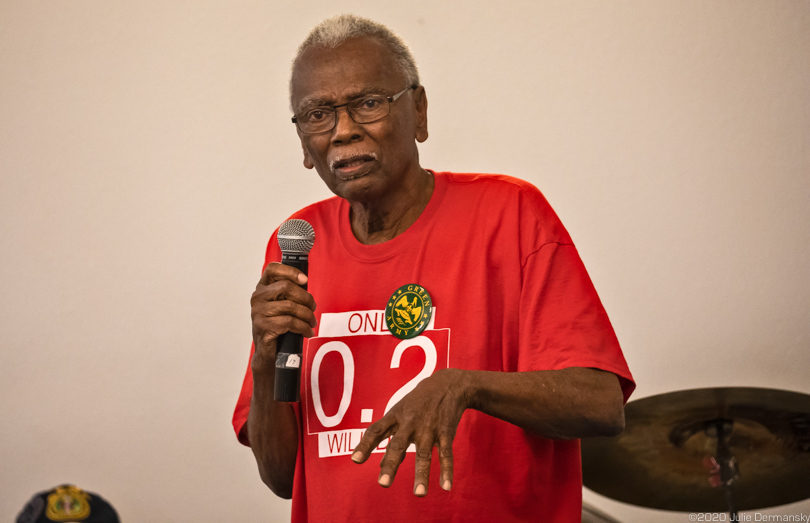

Wilma Subra, a technical advisor to the environmental advocacy group Louisiana Environmental Action Network going over data on the reported chemical releases during the public meeting in Baton Rouge a week after the fire at ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge refinery.

Flares at ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge facility seen from the Star of Bethlehem Baptist Church’s parking lot.

“Everyone in the community has the right to be safe and secure in your homes,” Louisiana Senator Cleo Fields, a Democrat representing Baton Rouge, said at a community meeting he organized a week after the fire. Flares were visible from the Star of Bethlehem Baptist Church’s parking lot where the meeting was held, near Exxon’s 2,100-acre complex that includes the refinery and multiple chemical plants.

At the meeting, Fields promised to craft legislation aimed at improving emergency notifications, implementing 24/7 real-time air monitoring, upgrading the current supply of safety devices, and establishing a clear and transparent emergency plan for chemical facilities and refiners statewide.

Living in Cancer Alley

For residents near Exxon’ refinery and adjacent chemical plants in Baton Rouge, a sense of safety and access to clean air are not a given. The plants lie at the northern end of Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, an 80-mile stretch along the Mississippi River with more than a hundred petrochemical plants and refineries woven among the river’s communities. Another nickname for the region is the “Petrochemical Corridor.”

Flare at ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge facility on February 19, 2020, a week after a fire at the facility.

Community members throughout Cancer Alley have deep rooted skepticism of industry, stemming from decades of living close to facilities that periodically experience spills, fires, and releases of high doses of pollutants, which many believe have led to a pattern of cancer diagnoses and other illnesses associated with chemical exposure.

Despite already hosting communities with elevated cancer risk from air pollution, Louisiana continues to permit a rising number of petrochemical plants along the Mississippi River in primarily African-American communities. Residents and environmental advocates have accused the state of allowing industry to turn low-income neighborhoods of color into sacrifice zones.

A Longstanding Air Pollution Battle

The same night as the fire at Exxon’s refinery, a citizens group in St. John the Baptist Parish held a community meeting about toxic air emissions from a synthetic rubber manufacturing plant located in the middle of Cancer Alley.

Denka plant in St. John the Baptist Parish.

In 2016, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began rigorously monitoring chloroprene, a likely human carcinogen, near the Denka Performance Elastomer manufacturing plant after it determined that those living closest to the plant have a 50 times greater chance of getting cancer from airborne toxins than the national average.

At the February 11 meeting, David Gray, a regional EPA official, explained changes that the agency is making in the way it monitors chloroprene, which the community has been exposed to for over 50 years.

David Gray, a regional EPA official, explaining changes the agency is making to its ongoing air monitoring of chloroprene in St. John the Baptist Parish.

The Denka plant, formerly owned by Dupont, has voluntarily cut its emissions dramatically since 2016, but EPA air monitoring shows that chloroprene levels are still often dozens of times higher than the lifetime exposure threshold recommended by the agency.

Denka has challenged the EPA’s standard, compelling the agency to formally review its findings, though it stands by them. At a 2019 community meeting, Gray told attendees that the EPA, despite classifying chloroprene as a likely carcinogen in 2010, will likely never set a legal standard for the chemical, which is produced at only one plant in the U.S. He explained that the rule-making process was time-consuming and expensive, and that the agency’s resources were limited. The agency has only set rules for chemicals used by multiple plants and those rules require a laborious five-year creation process.

Instead, the EPA is trying to figure out measures that can bring emissions levels down faster with Denka’s cooperation. This month, Gray explained that changes to the EPA air monitoring system will be able to detect “spikes” in chloroprene and could help the agency determine the cause of continued emission spikes and lead to ways to further limit emissions.

The community expressed frustration that Gray couldn’t offer many details about the new monitoring system. He explained that EPA has yet to work out all of the details.

Lydia Gerard, right, a member of the Concerned Citizens of St. John, expressing her concerns to David Gray, a regional EPA official, at a public meeting on February 11, 2020.

The main frustrations stemmed less from concerns about changes to the air monitoring system than from the failure of the EPA and LDEQ to force Denka to cut emissions to EPA’s recommended standard.

“We don’t want more tests and studies,” one community member said. “We want action.”

Even though the EPA has not set a legal limit for emitting chloroprene, the State of Louisiana has the power to force a company to cut emissions if it believes they are causing a health emergency. Chuck Carr Brown, head of LDEQ, told St. John the Baptist Parish councilmember at a 2018 council meeting that the state can limit the company’s production, which would cut its emissions, but he has not opted to do so. “If I can’t get to the numbers we need to, production reduction is not off the table,” he said at an April 22, 2018 parish council meeting.

LDEQ Secretary Chuck Carr Brown at an April 24, 2018 meeting.

I asked LDEQ if the agency is planning to require Denka to cut production, but was told that the agency would not comment due to pending litigation, referring to a class action lawsuit.

At the February 11 community meeting, lawyers representing residents of St. John the Baptist in that class action lawsuit against Denka questioned Gray about potential coziness between the federal regulator and the company. They brought up 2019 emails between him and an official at Denka which suggest a close relationship between the EPA and Denka.

Gray vehemently defended his emails, assuring the community of his commitment. “It is not my intention to come here and undercut you in any way,” Gray told St. John the Baptist residents. “I am committed to this project … It breaks my heart to make you think anything else.”

Lawyer reading EPA emails at a public meeting and EPA official David Gray’s response

Robert Taylor, director of the Concerned Citizens of St. John, speaking at a meeting on February 11, 2020.

“Four years after learning about chloroprene dangers, children still attend the Fifth Ward elementary school right next to the plant,” Robert Taylor, director of the Concerned Citizens of St. John, said during the meeting. He expressed disgust that authorities have not relocated the students away from the polluting plant. “We need to protect the children!”

Turning Awareness Into Change

Lt. General Russel Honoré, founder of Louisiana’s Green Army, a grassroots anti-pollution coalition, attended the recent meetings about Denka and Exxon air pollution. He hopes the increased public engagement over air pollution concerns will help move the state legislature, which in the past has resisted mandating additional air monitoring, to pass state Senator Fields’ bill currently in the works. He believes people need and deserve access to real-time information to better protect themselves and their families from the serious risks of living near the oil and gas industry.

Lt. General Russel Honoré speaking at a February 11, 2020 Baton Rouge community meeting.

During the meeting in Baton Rouge, Honoré encouraged the crowd of about three hundred to stay engaged. He also issued an angry warning about public trust to the media, first responders, and Exxon representatives: Stop telling the community that “nothing left the plant” like they did while the refinery fire was still ablaze , because in doing so, “you have lost all respect from the citizens.”

Main image: Entrance to ExxonMobil’s Baton Rouge refinery on February 19, 2020, a week after a fire at the facility. Credit: All photos and video by Julie Dermansky for DeSmog

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts