This piece is about what we talk about when we talk about ‘climate change.’

Mostly, whether in the campaigning world or the policy world, the tech world or the business world, the everyday world or the world of international summitry, we mainly talk about cutting carbon emissions. And if we talk about impacts, we talk about the impacts of global heating, plus the impacts of the growing chaos.

But we don’t talk enough about climate impacts, our vulnerability to them, let alone how to prepare adequately for them, or to tackle them ‘upstream’ before they land or get worse. And if we talk about chaos, we virtually never talk about it in a big enough context, or in terms of its full potential dimensions.

This article is designed to start to change that situation.

The recent unprecedented worldwide epidemic of flooding, followed swiftly by the dire Los Angeles fires has woken another significant tranche of people up. Devastating climate impacts are here. Climate chaos is here. The adaptation challenge should now be getting strategic pre-eminence. That it isn’t is a key marker of how far off the pace the dominant (still decarbonisation-centric) climate narrative now is.

And the growing evidence of the true scale and nature of the coming chaos should decisively change that narrative.

As Ice Melts, Some Places Can Cool

Our future is far more complex than the simple narrative of ‘global warming’ suggests, and we need to be prepared for a range of outcomes, distributed in different regions, that include both extremes of hot and cold.

Our knowledge concerning the climate is of course growing all the time. But it would be fatal hubris to assume that this means that the level of uncertainty concerning what will happen in the future is concomitantly reducing. If anything, the uncertainty surrounding our climate is growing at present, because we are finding that the Earth-system is behaving in novel (and dangerous) ways as it moves literally into Terra Incognita that we didn’t fully anticipate; and because the destabilisation of our climate is having some very counter-intuitive effects.

Our actions have inadvertently created a hot new world that is more and more difficult to understand, let alone predict, let alone ‘control’.

In short, the uncertainty surrounding our climate is growing, and with it, the probability that countries such as Britain and (the eastern seaboard especially of) the United States (like other countries bordering the north Atlantic) might face a future that’s not just hotter, but ironically also (before long) colder.

Why? Because of the escalating Arctic ice-melt, which could lead the North Atlantic Gyre ocean current system, and perhaps the larger system known as the ‘Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation’ [AMOC], to slow, or even stop. These alarming, growing possibilities have entered the media recently; but they’re yet to be absorbed into the vast majority of climate campaigning, preparedness, and policy.

Most people know these complex ocean current systems mostly only through the phrase ‘The Gulf Stream’, which Britons understand keeps our climate warmer than Labrador in Canada (which is on the same latitude as us). If the Gyre caves in, or worse still if AMOC collapses, in the coming decades, our climate could plunge us into conditions more akin to Siberia than to Spain. What is known as ‘the Gulf Stream’ would more or less switch off. The question then is not merely the already tough one of how we prepare for the coming global overheating; the far more complex question is, how do we simultaneously prepare for both hotter and colder climates?

Why This Matters

Consider this in terms of kinds of adaptation measures that require multi-decadal planning: the planting of orchards and the initiation of reforestation projects, for instance. We literally don’t know whether our climate in the UK will be hotter or colder, by the time any trees we plant now mature.

The core of any answer to this particular conundrum teaches us an exemplary lesson: Plant highly diverse species and varieties.

It is certain that some (probably, many) trees and tree species will be knocked out by the coming global overheating with potential regional cooling (we don’t know which, yet). We of course need our ecosystems to remain relatively functional and resilient no matter which future comes. So in the UK we need to plant native species and varieties; and Mediterranean ones; and Scandinavian ones.

A shift in thinking such as this represents a profound change in how we view our role in shaping (and in being shaped by) the environment. We must move away from trying only to prevent change, and instead focus increasingly on actively shaping the — uncertain — biotic transformations that are now coming and that in one way or another are inevitable.

In short, the challenges ahead demand that we think bigger, more diversely, and more proactively. We can’t afford to cling to outdated conservation strategies, for instance. Instead, we need to embrace a new approach, one that recognises the full spectrum of climate (and wider ecological) breakdown, and prepares our ecosystems to adapt, no matter what the future holds.

Policy-makers are to an astonishing degree missing the point about the situation we’re in: which is one of far greater uncertainty than most like to admit. Which only makes our situation more parlous, and genuine precaution more urgent.

Consider a very pertinent example in the UK: the drive to decarbonise our electricity supply, one of the new Labour government’s flagship policies. Remarkably,there are no plans for the new pylons and power lines to be hardened against a colder future. Why? Because the powers that be and the National Grid are assuming that the future here will be hotter.

Or take a more prosaic example: Consider a TV show like the BBC’s widely watched Gardeners’ World. The emphasis there is nearly all on ‘how we will cope with a warming climate’. This is encouraging insofar as it shows quotidian adaptation in the making. But as I’ve noted, some models now suggest that there is about a fifty-fifty chance that actually within the lifetimes of most of us, and possibly very soon, we could well have to be coping with a cooling climate, here in the UK.

We are so badly unprepared for what may be coming. We badly need a major mindset — and practice — shift, towards strategic adaptation.

Psychological Barriers

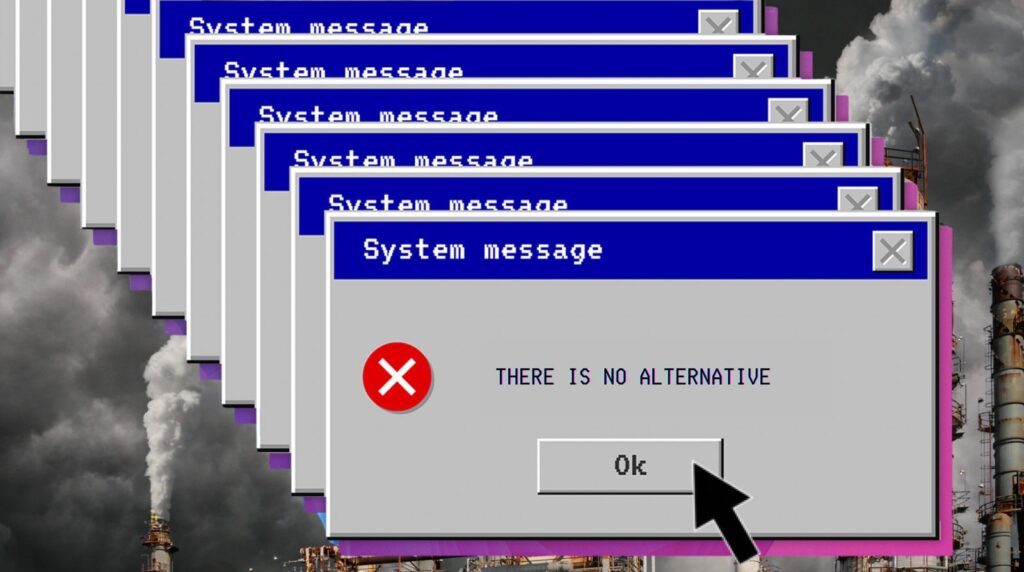

Why has this kind of change, which is so utterly critical to how we adapt and prepare (and to our understanding of the degree to which we have, to use a technical term, f**ked up our climate), not yet been absorbed into public consciousness? I suggest that it’s because people (elites and the public alike) have only just started factoring in the epochal shift to genuinely thinking of our future in terms of a trend of dangerous overheating. It’s proving too much, for nearly everyone, so far, to make a big further shift, into the bitter truth: of wild uncertainty about what our future climate holds. The mind recoils at such uncertainty; it seems to leave so little to cling onto.

We need a degree of hedging, and to allow ourselves to live in a world we accept that we’ll never fully understand. But that’s in direct tension with central narratives — of ‘predict and control’, of progress, of human hegemony — that have dominated our thinking since the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment. No wonder so many of us resist the shift to a more accurate emerging paradigm of climate breakdown and radical uncertainty, requiring in its wake deep precaution and a new (and, in truth, also old) humility.

Perhaps it isn’t just that we’ve left the Holocene behind. Arguably, we’re already leaving the Anthropocene behind too. We’re entering into a long period in which our efforts to be as gods have actually produced the opposite: a chaos that outstrips our understanding, let alone our control.

Call it the Chaoscene?

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts