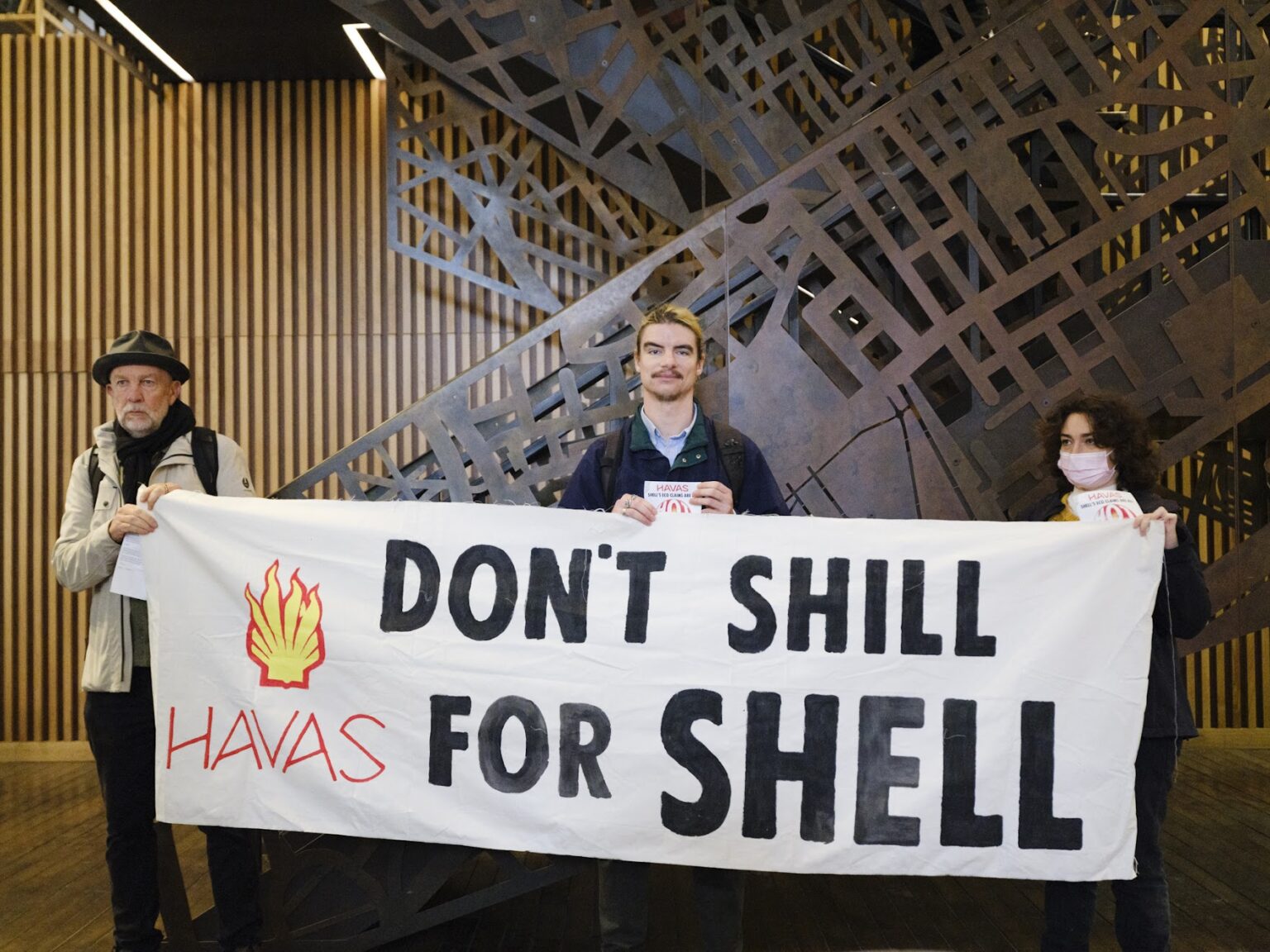

Paris-based advertising giant Havas has warned investors of the reputational risks associated with its work for fossil fuel companies in the latest fall-out from its decision to work with UK oil major Shell.

Havas, whose CEO Yannick Bolloré had repeatedly voiced concern over the climate crisis, faced criticism from climate advocates last September when news broke that one of its agencies, Havas Media, had won a major Shell advertising contract.

In July, B Lab — the nonprofit that awards “B Corp” status for high environmental, ethical and governance standards — withdrew the certification from four other Havas agencies in response to complaints raised over the Shell deal.

In a prospectus for a listing on the Dutch stock exchange, Havas disclosed risks including that it “may fall short of stakeholder expectations relating to ethical, environmental, social and governance considerations” in ways that could “materially adversely impact the Group’s business.”

Havas said that it was likely to continue to face “negative publicity” based on the identity of its clients, including those in the fossil fuel, defense, tobacco, and alcohol sectors, as a result of “the public’s (or certain segments of the public’s) view of those clients.”

The prospectus did not mention Shell by name, though it referenced the stripping of B Corp status from the four Havas agencies.

Havas made no equivalent warning over the reputational risks of working with fossil fuel companies in its last annual and corporate social responsibility reports published before the Shell deal was made public.

‘Significant Negative Publicity’

In the prospectus, Havas said that the B Corp ruling “has not to date resulted in any material adverse effect on the Group’s financial performance,” though it conceded that the group suffered “significant negative publicity and corresponding reputational harm.”

The prospectus warned that growing pressure on Havas might make it harder to work with new clients viewed as “harmful to the environment or otherwise negatively perceived.”

Havas published the prospectus as part of its preparations to list on the Dutch stock market in December amid plans by parent company Vivendi to split its assets.

Havas’ warning, first reported by trade press including Campaign and PR Week, is the latest move by the world’s largest communications groups to acknowledge the reputational risks of working with major polluters.

In a 2023 sustainability report, the Japanese ad giant Dentsu acknowledged it could face declining revenue and reputational risk if it were to serve clients that fail to decarbonise. “Our ability to attract and retain clients, business partners, employees and other stakeholders will depend on maintaining a reputation as a climate leader,” it said. According to DeSmog research, Dentsu continues to work with fossil fuel companies including Chevron, ExxonMobil and Shell.

In 2022, New York-based Interpublic Group announced that it would proactively review the climate impacts of prospective clients in the oil, energy and utility sectors. However, this commitment does not apply to its subsidiaries’ existing fossil fuel contracts with companies including Saudi Aramco and Equinor.

In October 2023, Bolloré, the Havas CEO, told Campaign that he had been happy to pitch for the Shell account, saying “we believe the most effective change comes from within.”

“We won’t participate in any greenwashing whatsoever and we will accompany [Shell] and help achieve their transition,” Bolloré said.

In August, the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority watchdog began reviewing a Shell campaign called ‘Powering Progress’ that ran on UK television in the first half of the year in response to complaints that it painted a misleading picture of the company’s role in the energy transition. ‘Powering Progress’ was the first Shell campaign that Havas had worked on since winning the account, according to Ad Week.

Ad giants such as WPP, Omnicom and Interpublic Group score highly on the rankings used to gauge a company’s sustainability performance — so they’re attractive to green fund investors.

However, a DeSmog investigation found in February that these scores take little or no account of multiple risks associated with the advertising and PR industry’s role in the climate crisis — from reputational damage caused by greenwashing fossil fuel clients, to threats to staff retention, and the danger of being sued for climate damages.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts