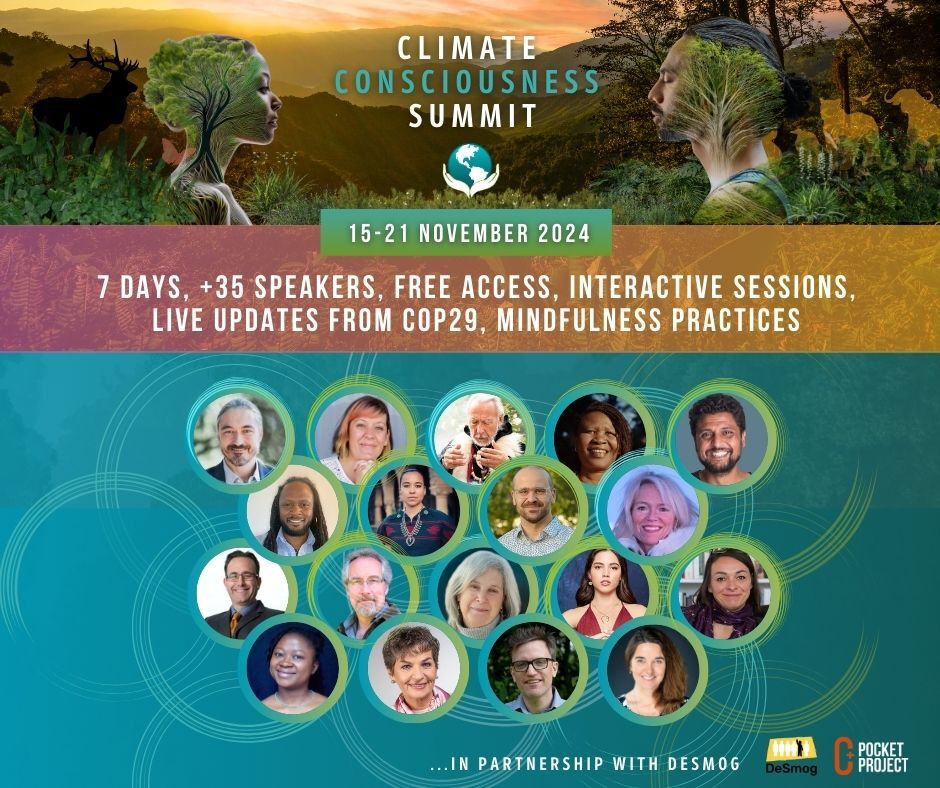

In an interview for the Climate Consciousness Summit 2024, staged by the Pocket Project in partnership with DeSmog, Kosha Joubert, Pocket Project CEO, spoke with Immad Ahmed, founder of the Humanitarian Assistance Program about his work to support refugees and displaced people hit by the climate crisis.

Ahmed has been working with internally displaced people in Bangladesh since 2013, and latterly with Rohingyas who fled to Bangladesh from Myanmar. He has also worked to support displaced people living in camps in South Sudan.

In a video conversation that will go live during the November 15-21 Climate Consciousness Summit 2024, Ahmed spoke from Bangladesh about his use of an approach known as “human-centered design” (HCD) to help people displaced by violence, and exposed to escalating climate impacts, regain a sense of agency.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Kosha Joubert: Very few people can imagine life in a refugee camp. Could you share your experiences working with vulnerable and displaced communities in Bangladesh and South Sudan?

Immad Ahmed: When the influx started in 2017, we had about 270,000 Rohingya crossing the border from Myanmar to Bangladesh escaping genocide. Now, seven years later, we have roughly 900,000 people living in one of the largest, most densely populated refugee camps in the world.

Bangladesh’s specific positioning makes it one of the most adversely affected countries regarding climate change. Over the past few years, we have just seen the scale of that increase and the frequency of weather-related disasters increase. And how we respond to those is becoming even more critical. Take the perspective of the refugee camp, it adds on to the complexities that the refugees have already faced in the past seven years; the only shelters and infrastructure that we have for refugees are made out of bamboo and we’re working on permanent solutions, but we still have policy challenges limiting what kind of interventions we can create.

So imagine when we have cyclones coming through every year, and almost every year we’ve had a cyclone. And this past year, we had two, which makes the people in the camps very susceptible to the winds, the rains, and all the impacts of flash flooding. We’ve had a massive increase in landslide issues within the camps because of the over-saturation of the ground. The landslides can collapse areas, killing an entire family, so the compounding risks for refugees and displaced people are just going through the roof above what vulnerable populations like in Bangladesh are already facing here. This is something that we are seeing as a trend everywhere.

Joubert: I would love to zoom in a bit more on working with young people. With this level of hopelessness, what happens in young people?

Ahmed: This is where it gets complex. Where there is poverty, we have challenges with crime and every other negative aspect. The numbers, statistics, and research are substantial on this. When we have poverty issues, especially in countries like Bangladesh, South Sudan, Pakistan, and India, we have issues of gender-based violence going up. We have problems with child protection, and human trafficking goes up.

Education is one of the foundational challenges to engaging and empowering youth the right way. I have a different perspective, and I’ve been very honored to be able to work with fantastic youth from these communities. And I’ve seen that if you can provide youth with guidance and resources, they can accomplish almost anything, and I’ve seen that firsthand in the refugee context in South Sudan, Pakistan, and everywhere. I know the power of youth for sure. Not only do they mobilize their communities, but they also mobilize their families and everybody else. And that’s where the strength of community resilience truly comes from.

The weather patterns in these areas are changing at a massive level, and the people do not have the coping mechanisms to respond. Not only do they not know what’s truly happening, we have to understand that literacy levels are low. So we, as experts and humanitarians, I don’t think we’ve done an adequate job of relaying how these communities will be impacted by climate change and how we need to build the resilience of communities from the ground up.

I’ll give you an example I used about South Sudan. When I worked with the women there, I asked them, Why do you think these floods are happening? They say, look, it’s a once-in-a-lifetime century flood, and we’re just waiting for a change. I spent a day with them talking about climate change. Again, these are women who have phone apps and have never been to school. They can barely read and write, just very casual conversation. By the end of the session, they were able to understand why [climate change] is happening and also understand that the predictions for this area aren’t once in a lifetime, this is going to happen frequently every year. That changed their perspectives and gave them more resilience to do something about it instead of waiting.

Joubert: I notice there’s grief about what is happening and also a sense of overwhelm. I would love to go back to when you talked about climate change with the women in the South Sudan camp. What are the kinds of solutions that people can come up with, especially in terms of young people? I would love for you to speak to that and also explain to us what human-centered design is.

Ahmed: When my journey in this area started, it became very clear that the people themselves were the best ones to solve these issues. And if we talk about sustainability, how much can an agency be there and support the people? It starts and ends with the community. A long time ago, I realized that if you built up the community’s confidence over time, they would be truly empowered to create their ideas for solutions. I found it powerful when I first learned of human-centered design for practitioners or development people to go into communities and work and create solutions. The reason is that HCD is completely based on empathy. I think that is where it’s so powerful.

Take someone like me, who has privilege, who is coming from the outside. It forces me to take my personal biases and put them aside, and then talk to the community, learn from the community, gain a deeper understanding of the community’s needs, and then work with them to find solutions. What ends up happening is these youth, the women, the communities, they become agents of that change because they learn. They say, I have the skills, I can find out and learn. I don’t need to wait for anybody. As soon as that clicks in their minds, it’s a massive shift. It’s such a drastic shift I’ve seen that I’m always in awe of how powerful it truly is.

And suppose we wanted to economically show their impact on the social dynamics of it. In that case, it’s always positive outcomes, and that all comes back down to creating that confidence in the community and creating that grit in the community to keep being persistent. And the thing is, they don’t have a choice, right? They don’t have a choice but to adapt. They don’t have a choice but to be persistent because it affects them immediately. It affects their children and their lives immediately. So once they learn and we take them through our design process, we teach them how design thinking works and how it can help their communities. Then we give them a challenge. And then they come up with prototype solutions, test those solutions, and then put them into the community. This creates 21st-century skills around problem-solving, creative thinking, collaborative team building, and being resourceful. These are skills that are needed for today’s economy as well, right?

What we have them do is immediately start focusing on what can make their lives better immediately. And it’s always linked to economics, food security, or jobs. And when we show them that, and they do it, and they see the ability to come up with different solutions, and it works, this is a powerful driver for them to keep going.

As a little case example, in the South Sudan camp, we worked with the women because food security was a big issue. After all, they’re stuck in the camp. There’s no agriculture. There’s no land that they can grow what they’re used to. But there were a lot of water hyacinths, which is a plant that’s very common to Bangladesh. In South Sudan, the only thing they do with water hyacinth is when there’s absolutely no option, they eat it. And that’s the only thing that they did with it in the camps. But in Bangladesh, we use water hyacinth to create floating gardens because water hyacinth is buoyant.

So when you bound this plant together like a little bit of a bed, it floats. When the water rises and floods, this floating bed goes up and down so it doesn’t get hurt. If there’s flooding, it doesn’t get destroyed or washed away. Water hyacinth is also an amazing natural fertilizer and compost when it deteriorates. I showed the women in South Sudan what we did in Bangladesh and how to make these bundles of hyacinth and their potential. And they got so excited about trying this. We worked with them to prototype one idea in South Sudan about a year-and-a-half ago, and from that one idea, when they saw that it worked once, especially once they grew their very first vegetables on it, they knew that, no matter what, nothing could stop them.

Joubert: This approach puts the trust back, as you say, into the human being and the creative potential of that human being. It also means that just because we don’t fit into a Western box of what education looks like, we still have the wisdom that we create from a completely different reality in each human being.

Ahmed: Yes. This is something that I’ve encountered very recently, that when adults talk about youth, they don’t believe that they have the potential, or they look at youth from a personal, very biased perspective. But when you put that aside and you truly work with these communities, and you don’t lead them, you provide them a safe place to prototype ideas to learn from, when you build on ideas with their buy-in and self-agency, it goes a long way.

I think we must change how we work with vulnerable populations and indigenous communities. We’re talking about marginalized voices. We’re talking about the inclusion of voices, but we’re not allowing them to sit in the UN coordination system when we are designing and fundraising for them. That’s a gap; the global guidance on this is to include them. We shouldn’t have to advocate for this, this should already be part of the process. But it’s still not there.

You look at the UN system in general, we still have issues with giving voting rights for the continent of Africa in the UN system. Our systems aren’t robustly developed enough for the complexities of climate change, the frequencies of how it will impact, and the scale of how it will impact, because we’re still not prepared there. If we engage in the right way, we can solve so many of these things early on and have a lot more if it’s economically efficient. We can find sustainable solutions, but right now, we’re still using 20-year-old strategies for a world that was a little bit simpler then and not as complex a world that we’re dealing with today.

Joubert: I just want to highlight a few things you said. You’ve repeated a few times now that this human-centered design grows out of empathy and that empathy is a deep respect. You’re speaking about a certain entrance point for a healing movement to grow from.

Ahmed: The empathy aspects of the design thinking is the most important aspect. Many people think about child marriage. How could these people do it? It’s a cultural thing. But it’s not really, it’s you don’t have a choice, right? When you or your child have a family and you cannot provide for your children, you cannot give them water or food, then what is your choice? You’re going to find a solution for them that’s better, right? And that can be child marriage. That can be sending them off somewhere, like child labor, the list goes on. It’s not a cultural aspect. I think many people get the idea that these child marriages happen in underdeveloped countries and marginalized communities, and this is how they do things. But that’s not it. A lot of these are economic aspects.

We understand how important it is to educate girls. People understand it and want it. People want a better life for their children, but when they get stuck, they must make decisions to keep their children alive. And then the opportunities of all those negative coping mechanisms come up. Right now in Bangladesh, we have a massive issue. Ever since we had a funding crisis for rations, we have an uptick in human trafficking happening. Why? Because there is no future, there’s no food, there’s no education, there’s no jobs.

What choices do people have? Stay in the refugee camp for another 10 years, and no access to education? They will try whatever they can to survive. So that’s one thing I think, when I would just say to everybody listening, what would you do if your child was hungry for 10 days? What would your next step be? It’s scary to think about it, but once you close your eyes and think about it, you can put yourself in their positions, right? And I think that their complexities come down to economics and just wanting. People want the best for their children, their families. Everybody wants that. That’s a universal aspect. We all love our kids. We all want the best for our children. It’s about how much privilege you have and what access to those things you have. And when we talk about displaced people, refugees, specifically, they don’t have rights. They don’t have movement rights, they don’t have rights to access, so they don’t have privilege. And then what do you do that? And I’ll leave it to people to determine what they do next.

The other aspect in South Sudan I wanted to bring up was empathy. Empathy has a massive impact in the communities. There was a woman who was talking about issues with her neighbor, and then she used empathy and ways to look at the problem from another’s perspective and find solutions that worked for everyone. Otherwise, she said she probably would have fought with them and yelled, and it would have turned into a larger deal. But she said she was able to stay calm.

We had taught the women in the camp breathing exercises. So she’s like, I practiced your breathing exercises several times. I breathe in and breathe out. I got myself calm because I was very angry. And then she focused on, what does this person need? Why are they upset? And then, when she understood that, she said she had the tools to have a dialog and solve the issue, and it was just amazing.

I have so many other stories that we captured during that time in South Sudan. It was just so moving. These women have seen the worst. I mean, they’ve been through war, conflict, climate change, they’re in a refugee camp. They’ve seen it all. And for these women to come into that workshop and be so empowered to do something, take that agency into their communities and highlight the rest of their voices, it was just a beautiful thing to see.

I think that’s what is truly at the essence of human-centered design thinking. I think it’s about putting your personal biases aside and learning about empathy for everyone. Human-centered design thinking was created for practitioners to work with communities. We give the tools directly to the community and have them work with the rest of their community to build on top of that. They’re the ones leading it. We would just work and support them and inspire them. That resilience cascades through every aspect of that life, and it’s really empowering. That’s the beauty of human-centered design thinking, and that’s why, with all the youth and all the communities people work with, that should be center stage.

Register here for the Climate Consciousness Summit 2024.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts