This investigation has been translated into French. You can read it on DeSmog here

Flagship initiatives to ensure “responsible sourcing” for the global aquafeed industry in West Africa are being undermined by systemic conflicts of interest, endangering efforts to safeguard critical fish stocks, DeSmog can reveal.

The findings raise concerns at a time of growing evidence of the harms caused by the fishmeal industry in the region, prompting accusations of “greenwashing” from campaigners.

In the last decade, factories producing fishmeal and fish oil – the engine of the carnivorous fish farming industry – have proliferated along the West African coastlines of Mauritania, Senegal and The Gambia.

The industry targets small, oily ‘pelagic’ fish – such as sardines, sardinellas, and mackerel – which are ground down into ingredients to feed salmon, sea bass, and shrimp. They are part of the world’s fastest growing food sector – and demand for fishmeal and fish oil outstrips supply.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the industry’s operations are known to cause pollution, food insecurity, and job losses. Pelagic species, often known as the “fish of the poor”, inject essential nutrients into local diets, and provide employment to tens of thousands of women fish workers; the pressure on these already depleted stocks is putting them at risk of collapse.

DeSmog has mapped three sustainability initiatives active in West Africa since 2017, that were set up by powerful global players and buyers in the fishmeal and fish oil industry in response to these critiques. Participants include the U.S. feed-manufacturer Cargill, EU aquafeed producers Skretting and Biomar, and the marine ingredients trade group IFFO.

A certification programme, industry roundtable, and fishery improvement project were analysed, taking in membership, affiliations, and jobs of participants in the three interconnected and mutually reinforcing initiatives.

The study revealed representatives from West African civil society, women fishworkers, and small-scale fishers to be absent from all three, despite local stakeholders and communities bearing the brunt of fishmeal industry impacts.

DeSmog also found that aquafeed giants Cargill, Skretting, and BioMar – three of the world’s biggest suppliers of salmon feed – are represented in all three initiatives. They also sit on oversight committees of the certification programme MarinTrust, which is the main standard-setter for the fishmeal and fish oil industry.

The three companies are already actively sourcing fish oil from Mauritania, despite its pelagic fishery not yet being certified as sustainably managed. All have plans to expand aquafeed production, and have published ambitious, short-term targets for increasing the proportion of certified marine ingredients in their aquafeed.

DeSmog’s analysis showed that representatives from corporations and their trade groups dominated the board of the standard-setter and the Global Roundtable on Marine Ingredients. Three of these organisations also had a history of opposing environmental regulations.

Industry representation was not balanced by either NGOs or independent research institutes at an executive level, with just two, international conservation non-profits represented across the three initiatives.

MarinTrust’s governing structures also revealed it to be fully controlled by members of the marine ingredients organisation IFFO, the trade association for the fishmeal and fish oil industry, with whom it shares a London address.

“How seriously can you take a certification programme if it’s just the companies developing their own sets of criteria, and then they are the ones who hold the reins on any kind of accountability?” said Devlin Kuyek, a researcher who focuses on global agribusiness at the non-profit GRAIN. “There’s nothing to really check power in any of that.”

Aby Diouf, a fish seller from Senegal, commented: “We are in organisations, we have our presidents. But that doesn’t mean we’re asked for our opinions, and our representatives are not there when decisions are made. We would like to be part of it, because like that we could defend ourselves. The fishmeal factories do not serve us.”

In a statement, a MarinTrust spokesperson described the body as an “industry-led initiative, whose credibility comes from its deep knowledge of the marine ingredients sector: the industry, the certification sector and the NGO landscape are represented in its governance.” MarinTrust held public consultations to ensure stakeholders’ feedback is listened to, they added.

MarinTrust also emphasised that its “model lies on setting the standard, NOT granting certificates – this is undertaken by an independent third-party certification body”, adding that it is a “member of [the global membership organisation for credible sustainability standards] ISEAL and complies with its codes of good practice”.

All organisations and individuals mentioned in this story were contacted for comment. A set of responses from MarinTrust, Roundtable, and IFFO can be viewed here.

A Powerful Global Industry

DeSmog analysed information collected from the voluntary initiatives’ websites, as well as past and present employment histories from LinkedIn profiles, to determine which companies, individuals, and civil society groups were participating.

Figure 1: Interactive map of industry influence in West Africa fishmeal sustainability initiatives

Figure 1 caption: Actors running three industry-led fishery protection schemes with a West Africa focus. Left to right: listed partners of fisheries management programme the Mauritania Small Pelagics Fisheries Improvement Project (FIP), members of sustainability initiative the Global Roundtable on Marine Ingredients, and the primary affiliations of fishmeal and fish oil certification programme MarinTrust’s Board and Governing Body Committee members Credit: Brigitte Wear and Michaela Herrmann

DeSmog mapped and analysed three overlapping industry-led initiatives focused on West Africa (see Figure 1). The study reviewed the 21 partners of the Fishery Improvement Project, which is led by industry in collaboration with the Mauritanian government, and was set up by French fish oil refiner Olvea.

The study also examined the affiliations of the 39 committee members of certification programme MarinTrust, and the 14 members of the Global Roundtable on Marine Ingredients.

Both were set up by the influential trade group IFFO, whose principal objective is “reputation management” in the face of what it sees as “much negative and unfair criticism” of the industry.

IFFO’s members are responsible for more than half the world’s fishmeal and fish oil production and 80 percent of its trade globally. Members include some of the world’s biggest producers of salmon, which consumes 44 percent of the world’s fish oil and had an estimated global market value of $16 billion in 2022.

The trade group describes marine ingredients – fishmeal and fish oil – as the foundation of the farmed seafood industry. Made from organisms such as small fish, krill, and algae, the majority of marine ingredients are used to make feed for the growing market of farmed fish, with pig feed, pet food, and nutraceuticals (supplements for humans) also important destinations.

The fishmeal and fish oil industry is often criticised as an inefficient use of resources for its reliance on wild-caught fish to feed other animals. It also stands accused of ecological harms: causing pollution, driving illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing, and depleting the marine food web for seabirds and other sea life.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has found that “the industry constitutes a threat to the livelihoods and food and nutrition security of local communities”. Consumed fresh or dried, small fish are a vital – often irreplaceable – source of zinc, vitamin A, iron, calcium, and fatty acids, particularly for children in their first 1,000 days of life, eaten by people living in both coastal regions of West Africa and further inland.

In 2023, factories in Mauritania used a volume of wild-caught fish that could have provided between 6 and 9.6 million people in the region with a year’s supply of fish sufficient to meet all their nutritional needs.[1]

MarinTrust’s Trade Group Ties

Consumers and retailers increasingly demand that farmed fish be fed on certified raw materials, but there’s a gap in supply.

More than half of the world’s fishmeal and fish oil production is certified against the MarinTrust standard; the programme has a 2025 target for 75 percent of all marine ingredients to hold its certifications, be in assessment, or be in a pre-certification “improver programme”.

MarinTrust started out life as the IFFO Responsible Standard (IFFO RS) in 2009, set up by the trade group IFFO in response to the “growing need for reassurance on sustainable fishing by the value chain”.

It aims to: “improve responsible fishery sourcing and production of marine ingredients globally” via standard-setting for fishmeal factories, processors, and traders, and programmes for factories sourcing from “improving fisheries”.

The IFFO RS standard rebranded as MarinTrust in 2020. It has previously rejected claims that it is a “quasi- in house certifier” for IFFO, stating on its website that it is a “separate entity with its own governance structure, articles, purposes and budget”.

But DeSmog’s analysis revealed MarinTrust and IFFO to have extensive and enduring ties.

Analysis of the affiliations of its members show MarinTrust to be fully controlled at board level by the marine ingredients trade group. Out of its six directors, four currently hold executive or very senior positions at IFFO, including its technical director (who is mandated to be on the board under MarinTrust’s terms of reference and is also a member of its governing body), along with IFFO’s director general and two IFFO board members.

MarinTrust and IFFO are also registered at the same address in London, according to filings on Companies House.

Environmental non-profits Changing Markets Foundation and Feedback Global have previously criticised MarinTrust’s close relationship with the trade body. Kevin Fitzsimmons, professor of environmental science at the University of Arizona, likened the situation to “the fox guarding the hen house”.

“Having so many people from an industry trade association basically being the same people who are running a certification organisation makes no sense to me at all,” Fitzsimmons told DeSmog. “They’re not going to hold their own trade group’s feet to the fire.

“If anybody’s going to take these certifications at face value, they need to open up, and be more independent,” he said.

Petter M. Johannessen, director general of IFFO, said in a statement: “IFFO encourages its members to go well beyond compliance with legal requirements: adhering to voluntary certification standards is critical to demonstrate responsible sourcing and production.”

He continued: “Voluntary schemes are not an either-or approach: clearly a market-driven initiative, exerting market pressure, they complement regulatory frameworks and can help hold businesses accountable through safeguarding principles set by the ISO (International Organisation for Standardisation). They need to be credible from both an industry and a civil society perspective. This is ensured through public consultations and well-established governance mechanisms.”

Industry Participation

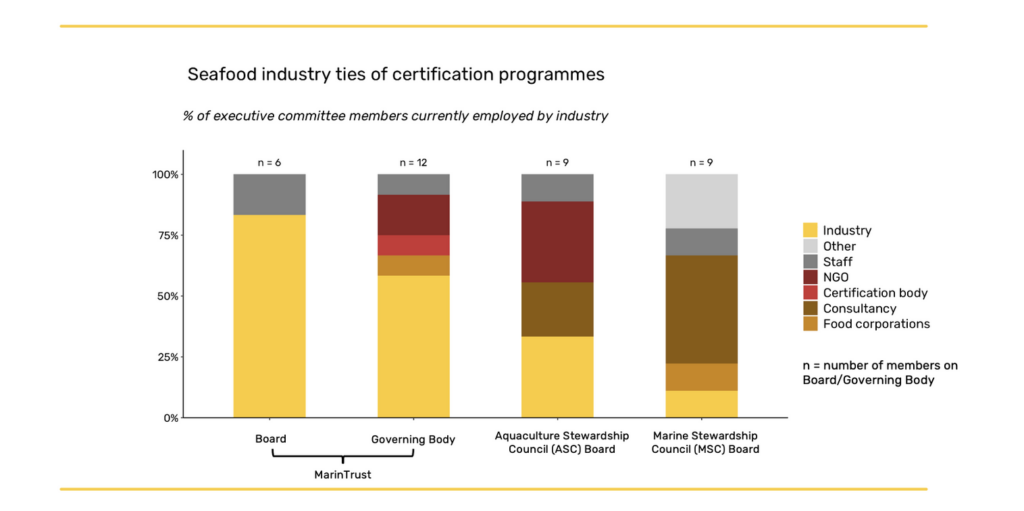

DeSmog’s analysis found that nearly 30 percent of MarinTrust committee members are currently employed within the fishmeal and fish oil industry, or the animal feed industry (as of May 2024).The analysis also revealed that MarinTrust had a significantly higher proportion of corporate and lobby group representatives on its board (83 percent) than comparable organisations, such as the Aquaculture Stewardship Council (33 percent) and the Marine Stewardship Council (11 percent) (see Figure 2.)

Figure 2. Seafood industry ties on certification programme boards

While MarinTrust does provide biographies for its committee members online, it does not publish their conflicts of interest disclosures, or its own funding sources on its website.

In total, eight corporations are represented between MarinTrust’s board and its governing body, whose responsibilities include revision and interpretation of the certification programme’s standards.

The governing body was home to major feed producer Cargill (which manufactures aquafeed and part-owns the Chilean salmon giant Multi-X), the Norwegian salmon company Grieg, Norwegian fishmeal producer Pelagia, Greek trader Distral and Veolys, and French seafood retailer Labeyrie Fine Foods. The chief executives of Peruvian fishmeal and fish oil giant TASA and Danish fishmeal trader FF Skagen were both present on MarinTrust’s board.

The analysis showed that in total five employees (directors, managers, and leads) currently employed by Cargill, BioMar, and the fishmeal giant Pelagia, sit on MarinTrust committees, including the Standard Steering and Technical Advisory committees.

In addition, all seven fishmeal and fish oil producers and traders represented on MarinTrust’s committees have sites that are certified to the MarinTrust standard. They include the corporations represented on MarinTrust’s board (TASA and FF Skagen) and Pelagia, whose CEO is also the current president of marine ingredients lobby group IFFO.

All three aquafeed giants present on MarinTrust’s committees have near-term goals to include a higher proportion of certified ingredients in their feed. BioMar has a goal to “source 100 percent of our marine ingredients from responsible fisheries by 2030”, Skretting is aiming for “100 percent of marine ingredients to be certified or from FIPs by 2025, with 85 percent from certifications and 15 percent from FIPs by December 2025”, and Cargill has “set an interim goal of sourcing all marine ingredients from certified or improving sources by 2025”.

MarinTrust’s structures were “highly flawed”, according to Dyhia Belhabib, fisheries program manager at the non-profit EcoTrust Canada. “It does not include any idea of the social perspective, nor any idea of true sustainability and its broader meaning”, she said.

“I support industry involvement in certification and sustainability programmes, but you have to ensure an arm’s length approach,” she said. “This is clearly built by the industry for the industry. If you include current industry members served by the scheme, that is a massive conflict of interest – it should not be allowed.”

Daniel Lee from the Global Seafood Alliance, who sits on MarinTrust’s Governing Body and Improver Programme Application committees, said in an email: “MarinTrust is a standard-setting body not a certification body and as such MarinTrust doesn’t certify anything. This separation of roles is fundamental in third party certification schemes – it amounts to ‘separation of church and state’.”

MarinTrust said in a statement to DeSmog: “The MarinTrust unit of certification is the facility, NOT the company / brand nor the fishery. MarinTrust provides assurances that certified marine ingredients are responsibly sourced and produced, NOT that they are sustainable.”

Despite this, all the major aquafeed companies Cargill, Skretting, and Biomar, have built their sourcing policies around MSC and MarinTrust’s certification programmes, and fishery improvement projects. Cargill cites sourcing “responsibly produced marine ingredients certified by MarinTrust” as an example of how they “help protect wild fish stocks”, while Skretting ranks MarinTrust as “sustainability class A”.

The Global Roundtable on Marine Ingredients

MarinTrust states in its annual report that it “continues to play a central role” in the West Africa workstream of the Global Roundtable for Marine Ingredients.

Also set up by the trade group IFFO, in partnership with the international marine conservation NGO the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP), the roundtable was established in 2021 to “tackle a range of pressing environmental and social challenges”, gather evidence-based information on the industry’s impacts, contribute to discussions, and “increase the availability of sustainable marine ingredients”.

The roundtable has no published criteria for joining, and membership is “by invitation”. The organisation would not disclose the names of company representatives to DeSmog, but Dave Robb, Sustainability Programme Lead at Cargill, confirmed his participation in this, as well as on the other two initiatives analysed. Its members also include six organisations that are also represented on the board and governing body of MarinTrust.

Among the roundtable’s 14 members are: Nestlé, which uses marine ingredients in pet food, infant milk formula, and fish oil supplements, and pet food manufacturer Mars. Nissui, a seafood company that owns salmon farms in Chile, is also present.

Aquafeed companies Cargill, BioMar, and Skretting, and the French refining and fish oil trading company Olvea participate in the roundtable, as well as EU aquaculture trade group the Federation of European Aquaculture Producers (FEAP), IFFO, and lobby group the Global Seafood Alliance. The only NGO on the roundtable is the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (see Figure 1).

“The roundtable is very dominated by feed producers,” noted researcher Devlin Kuyek. “It looks like an industry body that is there to protect their interests”.

Kuyek also highlighted that the companies mostly come from Europe and North America, and the absence of Chinese firms, which are another big buyer of fishmeal in West Africa. “It shows they have a particular set of interests that they’re concerned about, particular markets,” he said.

Mauritania is the seventh biggest exporter of fish oil to the EU. Along with Norway, the EU is an important market for fish oil, which is vital for optimising nutrition for salmon and trout.

In five years to 2021, Norway – the world’s biggest salmon producer – was consistently the largest importer of Mauritanian fish oil, accounting for over half of exports in 2021. France, Denmark, Spain, Greece, and Turkey were also regular importers of Mauritanian fish oil in the same period.

Kevin Fitzsimmons said the group looked like “industry talking to itself”, much like the MarinTrust board. “Most roundtables that I’m familiar with make a point of trying to get a bit of diversity in their membership, have some civil society, some government officials,” he said.

Árni M Mathiesen, the Independent Chair of the Global Roundtable on Marine Ingredients told DeSmog by email: “We believe that market pressure can create an enabling environment in which regulators feel confident to act. The Global Roundtable on Marine Ingredients was created as a single point of contact for stakeholders producing, using marine ingredients or setting standards for their responsible sourcing and use, with a willingness to drive positive changes in the sector through market pressure. We praise the Mauritanian government for implementing stricter regulations on fishmeal production back in 2023.”

Mathiesen drew attention to a report commissioned by the roundtable from an NGO, Partner Africa, which echoed previous studies by the UN and multiple NGOs, confirming that fishmeal factories in Mauritania and Senegal were polluting the air, water and soil, had caused food insecurity, especially for those on low-incomes, and had led to loss of work and income for women fish processors.

He added: “This platform does not set any sustainability criteria but rather relies on scientific data and third-party audits (such as Partner Africa’s report).”

The three participating aquafeed companies, Cargill, Skretting, and BioMar, all advertise their roundtable membership in annual sustainability reports.

Biomar states that it drives “more sustainable aquaculture” through its membership of voluntary initiatives, while Skretting says that by participating the company will help “… feed a growing population with safe and nutritious seafood proteins”.

But Kuyek did not believe the initiative would tackle food insecurity. “A roundtable dominated by industry will only contribute to worsening the situation, because it’s the increasing production of these commodities that’s the problem,” he concluded. “It just looks like 100 percent greenwashing.”

“Private initiatives driven by powerful multinational companies will make things worse,” agreed Andre Standing, senior adviser at the Coalition for Fair Fisheries Arrangements (CFFA), a platform of European and African-based organisations. “Any successful response must be based on transparency and public participation. That’s the opposite of a round table where people from West Africa are not invited.”

imageBROKER.com GmbH & Co. KG / Alamy Stock Photo

Roundtable’s Community Engagement

Standing acknowledged that West Africa partners may not want to be associated with the Roundtable. He suggests that instead, the group invite “observers” as an interim solution, pointing out: “It’s a very closed shop. It’s not open to public scrutiny, when it’s dealing with such important public goods.”

The roundtable hosted a workshop alongside the UN FAO and representatives of sub-Saharan African communities in December 2023. After, it issued “a joint statement that insisted on the need for the marine ingredients sector to be regulated, laws to be enforced and only raw materials with no market for direct human consumption to be processed into fishmeal,” Mathiesen told DeSmog.

Devlin Kuyek worries that UN collaborations are no substitute for accountability. “When they have initiatives with the FAO, it gives them added weight,” he said. “Because they’re not calling themselves the feed industry lobby group, but a roundtable devoted to sustainability.”

Diaba Diop, the president of REFEPAS, which represents more than 45,000 fishworkers in Senegal, attended the FAO/roundtable meeting in Ghana. “I talked about the difficulties related to these factories that women face,“ she said. “Our processing sector employs thousands of people and creates a lot of jobs but the fishmeal factory employs just a few people. And, on the other hand, fishmeal factories only make animal feed. Is it normal that we are going to feed animals instead of people?

“We do not have the same political power,” Diop added. “If we did, we would not have to advocate to the authorities, who authorise the factories, and we can do nothing about it. We always make our plea and meet people to raise awareness: that if the factories continue, the professions of women processors will disappear.”

A spokesperson from the seafood lobby group the Global Seafood Alliance (GSA) said: “Voluntary programs like those being promoted by roundtable members are critical, especially in regions where there is less stringent government regulation over these fishery resources.

“The GSA is a member of the Global Roundtable on marine ingredients because we are committed to following the principles of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. As part of this, we recognize that there are significant pressures on fisheries around the world for use in both animal feeds, as well as human nutrition. All these fisheries need to be managed in a way that promotes responsible sourcing practices.”

A spokesperson for Mars referred DeSmog to the Roundtable’s statement and its responsible sourcing policy.

A spokesperson from Skretting referenced the Roundtable’s Partner Africa report, with the following statement: “We believe that this bold action, combined with focus groups and workshops, such as the one co-organised with the FAO in Ghana, will drive positive change in these countries and position the industry at the forefront of the sustainable management of natural resources and dialogue with local communities.”

Lobbying History

DeSmog found that three of the companies and trade groups represented on MarinTrust and the roundtable have a history of opposing environmental regulations.

One group affiliated with a member of the MarinTrust Governing Body Committee, the European Fishmeal and Fish Oil Producers (EFFOP), had lobbied against a proposal to strengthen EU rules around permitted levels in fishmeal of the pollutant dioxin, a highly toxic and carcinogenic contaminant, while a roundtable member, FEAP, has lobbied EU bodies to “balance” environmental protection with aquaculture production.

Cargill has a poor record of both human rights and environmental abuses in its supply chain. It has previously lobbied and manoeuvred to block forest protections linked to soy, an accusation it denies.

Javier Ojeda, General Secretary of FEAP, told DeSmog: “We do not propose weakening EU laws on environmental protection. Our purpose is to highlight that we believe that many environmental protection measures to which EU fish farmers are legally binded do not provide extra benefits to the ecosystems; however, they create economic and social burdens.”

European Fishmeal and Fish Oil Producers (EFFOP) communicated to DeSmog that the EU’s proposal on dioxin limits would not be achievable with current technology. Their statement is published in full here.

‘Rubber-Stamping’ NGOs

The Sustainable Fisheries Partnership was the only NGO linked to all three initiatives. It was present on both the roundtable and MarinTrust, and describes itself as a supporter of the Mauritanian FIP.

WWF UK, another international marine conservation organisation, is the only other NGO identified in the DeSmog analysis that is involved at an executive level. It has a seat on MarinTrust’s governing body.

Both the Sustainable Fisheries Partnership (SFP) and the charity WWF UK receive significant funding from corporations. In 2022, the SFP received over $1 million from partnerships with corporations, nearly 20 percent of its turnover, while WWF UK received over $21 million in the same year.

SFP states that industry-driven solutions is “not just part of the SFP’s approach, it is SFP’s approach”. In 2022- 2023, SFP’s partners included U.S., UK and EU supermarket chains, McDonald’s, Nestle Purina and fishing giant the Thai Union group.

Andre Standing, from CFFA, was concerned that non-governmental organisations’ long-running partnerships, joint ventures and financial ties with corporations mean “they can no longer stand up and criticise their partners” and risk ending up in “rubber-stamping” or enabling conflicts of interest.

Multinational companies like those in the roundtable and on MarinTrust’s boards “only look respectable because they’ve got the partnership of people like SFP and WWF – it legitimises them,” he said.

Dave Martin, director of supply chain roundtables and social issues at the SFP, told DeSmog it accepts industry funding to assess fisheries, with results published on FishSource. Its findings “clearly highlight shortcomings and improvement needs in fisheries” and are “transparently based on science and are open to all to contribute to and critique”.

He added: “Voluntary action by the seafood industry has been useful in improving management in various fisheries, and helps create an enabling environment for policy makers to act. But permanent solutions to secure sustainable and equitable fisheries rely on enforceable legal frameworks.”

A representative for WWF UK said that it sits on MarinTrust in an advisory capacity and does not receive funding from any of the organisations. They added: “Companies and industries have a huge impact on the natural world and are highly influential on the global stage. There is more that companies can and must do, and for WWF, working to help change business as usual is key to tackling climate change and reversing nature loss.”

The Mauritania Fisheries Improvement Project

DeSmog also analysed the membership of the Mauritanian Small Pelagics Fisheries Improvement Project (or FIP) (see Figure 1). FIPs are market-based tools used to help fisheries improve their sustainability, with the goal of eventually getting certified.

The FIP is a private-sector initiative that brings in supply chain actors to support the Mauritanian government’s small pelagic management plan, which includes data collection, stock assessments, and enforcement of its rules.

Mauritania is the epicentre for the region’s fishmeal and fish oil industry, home to 29 factories, which in 2023 processed an estimated 350,000 tonnes of whole fish into fishmeal and fish oil.[2]

The FIP was set up in 2017 by French fish oil distributor Olvea, which, along with Cargill and Skretting, funds the project. It now has 23 partners, of which 70 percent are manufacturers or users of fishmeal and fish oil.

The remaining partners are connected to the Mauritanian government and include the coast guard, fisheries ministry, and the Mauritanian Institute of Oceanographic and Fisheries Research (IMROP).

Another FIP partner is Mauritania’s National Federation of Fishers (FNP)’s Industrial Sea Protein section (SIPM), which DeSmog was told by the FNP secretary, represents “only the factory owners”.

Harouna Ismail Lebaye, president of the artisanal fishers group FLPA section Nouadhibou, confirmed that artisanal fishers were not represented by this group, stating: “It is not possible to defend the wolf and the lamb at the same time. And that is the case of artisanal and industrial fishing.”

The Mauritanian small pelagic fishery was accepted onto MarinTrust’s Improver Programme in October 2019, becoming the certification programme’s first accepted fishery improvement project in Africa. It is now also aiming for the more stringent Marine Stewardship Council certification.

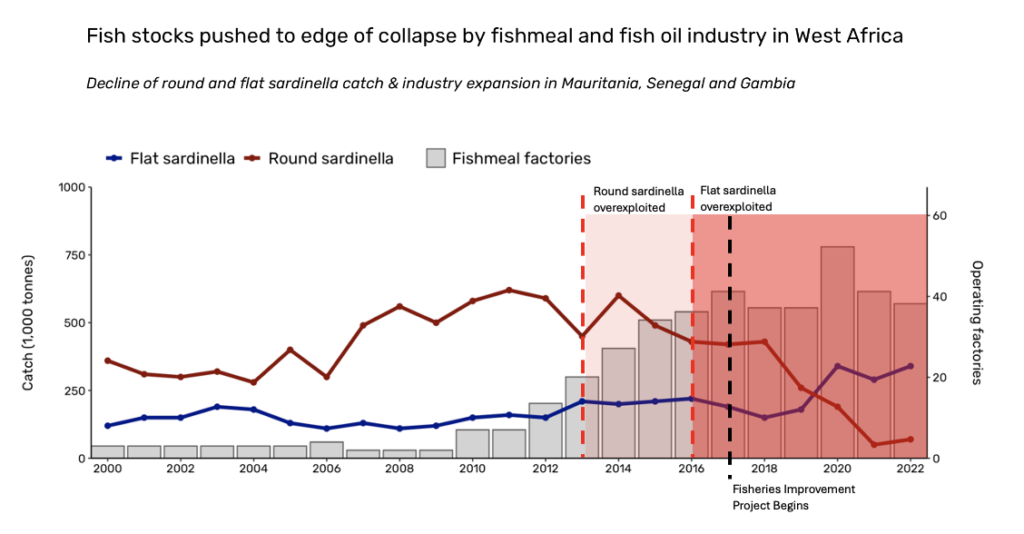

The FIP was set up, in part, in response to a dramatic drop in the stocks of fish targeted by the factories. In particular, the migratory stock of round sardinella – the star ingredient in neighbouring Senegal’s national dish thieboudienne – is in a critical state, according to the UN’s FAO.

With the growth of factories, which in 2018 absorbed 90 percent of the total pelagics catch, stocks of flat and round sardinella have dropped to their lowest levels in history (see Figure 3).

Figure 3

Companies Sourcing from Mauritania

Three of the four company FIP partners actively buy fishmeal and fish oil from Mauritania, although the fishery is not yet certified as “responsibly managed” under the MarinTrust standard.

Olvea sells 49,000 tonnes of fish oil per year, a third of which comes from Mauritania from its factory in Nouadhibou, the heart of the fishmeal industry.

Norsildmel – which is 50 percent owned by FIP partner Pelagia – imported 24,000 tonnes of Mauritanian fishmeal and fish oil between 2017 and 2020 – making it the fifth largest importer in the period. Pelagia’s CEO, Egil Magne Haugstad, is also the current president of IFFO.

Leading aquafeed companies on the FIP – Skretting and Cargill – told the Financial Times they source “small amounts” from Mauritania. Skretting and Cargill say they source from one of two factories, which are recognised as working to improve the fishery by MarinTrust. Cargill states that it sources sardines, while Skretting sourced sardinella in 2022.

Royal Canin has stated it will only source from the Mauritanian FIP when its “fish oil is MarinTrust certified”.

Beginnings of Regulations

Mauritania has rules in place to protect key fish species and improve collection and sharing of data. But while fisheries advocates have welcomed better transparency, enforcement is limited.

Since 2021, for example, Mauritania has stipulated that 20 percent of all fish brought into a factory must be frozen and set aside for human consumption. This rule was meant to help address the drastic drop in small fish consumption, for example in Senegal where it has halved in 10 years. But an official at the government research institute IMROP informed DeSmog that the set-aside frozen fish is exported to Asia, Europe, and Morocco.

As early as 2016, the Mauritanian government set a quota for fishmeal factories to limit production using whole fresh fish to 2,000 tonnes of fishmeal per year, with the remainder made from byproducts. But this does not seem to have been upheld.

A study published in March 2024 said 95 percent of fishmeal and fish oil is made from whole fresh fish (consistent with previous reports). Yet Mauritanian exports increased sharply after 2016, and the average production recorded in 2017 by the five FIP partner factories averaged at 10,660 tonnes – more than five times higher than the limit.

The rule also stated that the factories must reduce fishmeal production by 15 percent each year until 2019. Instead, Mauritania’s fishmeal and fish oil exports tripled between 2010 and 2020.

Since May 2021, round sardinella have been banned for use in fishmeal production in Mauritania, shifting the fishmeal fishing effort to sardines instead, which are not yet “fully exploited”, by the FAO classification.

A MarinTrust report from 2021 confirms the fishmeal industry is using greatly reduced volumes of round sardinella – a fact confirmed to DeSmog by FIP representative and statistics head at IMROP, Cheikh-Baye Braham, who said now “fish meal is mainly produced from byproducts and sardines, which are not widely eaten locally”.

But the same MarinTrust evaluation also “fails” the FIP controls relating to the composition of catches, and “landings declaration by species”. Meanwhile, a 2023 evaluation of the fishery by SFP states that illegal, unregulated and unreported fishing of sardines in Mauritania “warrants concern”. And despite the FIP and the government’s regulations, round and flat sardinella are still classified as overexploited by the FAO, as of 2022.

“I can understand the rationale behind industry, who have capital, looking to support fisheries governance in West Africa, and the Mauritanian government, who want a sustainable fishery, engaging with them,” says environmental social scientist Christina Hicks, professor at the political ecology group at Lancaster University.

“But fisheries management is always hard, particularly when fishing effort is driven by global market forces. It has taken 20 years of intensive fisheries management in nations with considerable resources and capacity to reverse stock declines.”

Hicks was not convinced the measures in Mauritania were equal to the scale of the problem. “Neither the capacity for intensive fisheries management nor meaningful engagement seems to be in place, as fishing has continued after the stocks were declared as overexploited and key actors do not feel represented. The risk is they legitimise the continued overexploitation of this crucial stock,” she said.

Sustainability Claims

Cheikh-Baye Braham from the Mauritanian FIP stressed to DeSmog that “regulation has been strengthened considerably in recent years”.

He added: “Any factory who would like to join can become a FIP participant. The objective is to be inclusive. Anything the FIP does is by its very nature voluntary. Regulated sustainability is the role of the government of Mauritania.”

The SFP told DeSmog that the presence of a FIP “indicates that various stakeholders have come together to fix issues in a fishery. It is not a claim of sustainability, and should not be described as such.

“All the members of the Mauritania FIP fully recognize problems in the fishery, which is identified as “poorly managed” in the most recent SFP report on reduction fisheries.”

Yet the sustainability and sourcing policies of the world’s biggest four aquafeed producers, Cargill, Skretting, BioMar, and Mowi, all state that they source from “certified fisheries, or FIPs”.

A former factory employee in Mauritania told DeSmog: “All the factories in Mauritania are trying to get into the FIP to get access to the European markets.”

Skretting told DeSmog in a statement: “Since our involvement in the small pelagics Fishery Improvement Project (FIP) we have continuously decreased our purchases from uncertified materials in Mauritania. From 2024, and in line with our Marine Ingredients Sourcing Policy, we will only purchase ingredients coming from the FIP.” It added that it shares its sourcing at the Ocean Disclosure Project and in its annual Sustainability Report.

The MSC told DeSmog in a statement: “There are no MSC certified fisheries in West Africa and we are not involved in the Mauritania fishery improvement project (FIP).”

For Belhabib, the fishmeal industry is fundamentally unsustainable. “It’s taking fish, a very good source of food, from the mouths of people in impoverished communities where the fish stocks are already not doing great. It’s environmentally wasteful. It’s not sustainable – it’s unethical.

“Having representation from the small-scale communities of West Africa, the people whose livelihood depends on these fish, is absolutely necessary. We have to stop thinking about them as just stakeholders. And think about them as rightful owners of the resource.”

The map was updated in August 2024 to include Biomar as a partner of the FIP.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Calculation methodology. 1) DeSmog took the reported volumes of fishmeal (FM) and fish oil (FO) produced in Mauritania in 2023 (FM = 71,370 t/ FO = 17,645t), which is equivalent to 350,000 tonnes of fresh fish, according to the 20:1 ratio of whole fresh fish required to make fish oil. 2) We took the recommended portion size of 100g of fish / person/ per day (= 36.5kg/ person/ yr)by EAT-Lancet, based on Hicks et al. 2019. 3) The upper limit of 9.6 million people assumes fish is eaten whole (100%). The lower limit of 6 million is a conservative estimate using the UN FAO’s edible portion sizes (62%) 4).The final sum = 350,000,000 kilos fresh fish/ year/ divided by 36.5 kilos/ per capita consumption. This methodology follows that used by Feedback in its Blue Empire report.

[2] DeSmog took the reported volumes of fishmeal (FM) and fish oil (FO) produced in Mauritania in 2023 (FM = 71,370 t/ FO = 17,645t), which is equivalent to 350,000 tonnes of fresh fish, according to the 20:1 ratio of whole fresh fish required to make fish oil.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts