After the Biden administration’s bipartisan infrastructure law was passed, the administration hailed the bill’s $4.7 billion package to cap orphaned oil and gas wells as a move to tackle “super-polluting methane emissions,” saying it will combat the climate crisis and create jobs. But it is possible that, without tight rules, these public funds could be spent in ways that contradict those goals — and go to the very entities that enabled these environmental messes in the first place.

Though the administration claims it will establish safeguards, currently there are no rules to compel state oil and gas regulators to use the federal funds in a way that prioritizes plugging the inactive and supposedly ownerless wells that are emitting the most methane, or even any methane at all. The law’s current implementation also offers no assurances that the new jobs promised for oil and gas industry workers will materialize, although it is a stated goal of the law.

Before the bill was signed into law last November, decarbonization consultant and self-described gonzo policymaker Megan Milliken Biven warned against granting billions of dollars to state oil and gas regulators to tackle America’s orphan well problem, advocating for a strong federal solution instead. Now in an attempt to safeguard the funds in what she describes as an imperfect bill, Biven is advocating for a set of rules she devised to govern the law’s implementation before the funds are spent.

“State regulators controlled by the oil and gas industry helped create this crisis,” said Biven when I met her in January 2022. “Are we really that naive to think the same puppets will fix it?”

Biven is a Louisiana native and a former U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management employee who founded and runs True Transition, an organization committed to making sure oil and gas workers have a seat at the table during the energy transition. She warns that without rules in place, it is possible that state oil and gas regulators — who have cozy relationships with the industry they regulate — could opt to clean up sites that clear the way for new carbon-emitting fossil fuel projects. She is also concerned that these same state regulators could select contractors who hire temporary workers or even prisoners to undertake the work, resulting in few, if any, permanent well-paying jobs.

Former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu, appointed by Biden to coordinate the implementation of the infrastructure law, holds the power to impose federal rules that ensure state regulators spend the money in a way that reflects the program’s goals to reduce methane emissions and create jobs. So Biven is determined to make sure her “Methane Memo,” which lays out a plan to safeguard the funds, makes its way to him.

Who Writes the Bills That Become Law?

Addressing the orphan well problem nationwide will be a massive undertaking. In 2018, only 2,372 orphan wells were plugged in the United States. At this rate, it would take nearly 900 years for states to plug the estimated 2 million abandoned oil and gas wells across the nation. This number grows every year as well owners walk away from ones that are no longer profitable. The new funding has also prompted the documented number of orphan wells being reported to rise radically in some states, since the amount of money states will receive is in part based on how many orphan wells they have.

More than a year ago, in a January 2021 Current Affairs article, Biven introduced her answer to this orphan well crisis: the “Abandoned Well Act” (AWA). This model piece of legislation she wrote calls for realistic bonding requirements that ensure well owners have enough money to plug a well when they are ready to walk away, and levy fees on the oil and gas industry to pay for future cleanups. Her solution calls for dismantling state control over regulating oil and gas wells, and for creating a federal workforce of oil and gas workers to locate, decommission, and monitor abandoned wells. While the AWA gained attention, it was never presented in Congress.

Instead, the portion of the infrastructure bill concerning orphan wells that is now law was written in large part by the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission (IOGCC), an organization closely linked to the fossil fuel industry. The law includes $2 million for the organization to consult with the federal government, making it a go-to resource for Landrieu when it comes to setting guidelines for spending the orphan well funding.

The IOGCC refers to itself on its website as a “multi-state government agency” but an Inside Climate News investigation built a case for the organization as a shadow lobby that played a leading role, along with Halliburton, in creating what is known as the Halliburton Loophole. This exempts the oil and gas industry from U.S. Environmental Protection Agency enforcement of the Safe Drinking Water Act as applied to fracking, “and is seen as what opened the Pandora’s Box for industrial high volume slickwater horizontal drilling in the United States,” as Steve Horn explained in a 2016 article he wrote for DeSmog.

Understanding who is pushing for federal funding to go to state oil and gas regulators who let the crisis blossom under their watch — and pushing back against federal guidelines to govern the spending of the funds — illustrates just how important it is to set meaningful guidelines on how the money is spent, Biven explained.

Biven described orphan wells as “an inevitable consequence” of allowing the oil and gas industry, and organizations like the IOGCC, to spend decades writing regulations. “Everything from the easy threshold to produce oil and gas in the United States, nonexistent environmental enforcement, plugging extensions, inactive and idle well policies, tax treatment, and finally financial security regimes conspire to produce this outcome.”

“In general it’s going to be a bitch to administer [the program] and there’s no reason to have 30 plus definitions of a single thing.”

– Megan Milliken Biven

Biven came up with suggested rules to govern the funding in a “Methane Memo” that, if adopted, will result in the federal money being used for the law’s climate and job goals. It points out deficiencies in the bipartisan infrastructure law’s handling of orphan wells and proposes nine solutions.

The first step addressed in the memo creates a national definition of an orphan well, rather than letting states set their own criteria. It recommends orphan wells be defined as “a well for which no operator or no predecessor operator can be located.”

“In general it’s going to be a bitch to administer [the program] and there’s no reason to have 30 plus definitions of a single thing especially when some states define an orphan well as when an operator is ‘unwilling’ to plug,” Biven explained in an email. The memo adds that not only will one federal definition make the program easier to implement, it will also protect against “fraud and abuse at the state level, where operators already exploit broad ‘orphan’ criteria.”

The memo recommends other forms of national oversight, including a national database to transparently track orphan wells and how the money to plug them is spent, as well as creating national plugging and restoration standards rather than letting states set their own. It also calls for repealing plugging extensions; setting uniform production thresholds for wells; better training, staffing, and funding for state inspection programs; and creating in-house plugging programs that will bring down costs when dealing with emergencies connected to the wells.

Methane Without Measure

Separate from the infrastructure bill, the Biden administration’s plan to reduce methane emissions from orphaned wells states that “priority will be given to the identification and plugging of super-emitters to maximize methane reductions that will be achieved under the program.” But, currently, many states lack the tools to look for and measure methane.

This concerns David Levy, owner of Petrotechnologies, a company that makes specialty parts for the oil and gas industry. In his spare time, Levy flies a small plane and monitors oil fields in southwestern Louisiana, transforming his flying hobby into an act of stewardship as he documents environmental hazards like oil spills and toppled storage tanks at well sites.

He was recently appointed to be a commissioner for the Louisiana Oilfield Site Restoration Program (OSR). As part of the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (LDNR), the OSR is responsible for selecting which orphaned wells from the state’s growing list of more than 4,000 are plugged, as well as which operators can bid on, and receive, jobs to plug the wells.

The commission is made up of 10 members, two from LDNR and eight appointed by the governor, primarily representatives from oil and gas industry advocacy organizations including the Louisiana Oil & Gas Association, the Louisiana Mid-Continent Oil & Gas Association, and the Louisiana Landowners Association (a group primarily representing subsurface mineral rights owners). It also has members from national environmental organizations and an at-large appointee, the seat Levy now fills.

Levy was dumbfounded to learn that in evaluating which wells to plug, OSR doesn’t consider which are emitting the most methane unless the amount of methane emitted is so extreme that it can be detected without instruments.

He says it is critical to measure methane emissions and factor those measurements into decisions about which orphan wells to plug first if the goal really is to reduce the methane leaking from them. In the absence of that, he has not been able to ascertain any logical process for prioritizing which wells get plugged first, and has questions about why the current sites were chosen from the state’s long list. This process that doesn’t account for methane emissions, he warns, creates a system that is easily gamed.

Patrick Courreges, communications director for LDNR, confirmed on a call that the department doesn’t have any tools to identify methane emissions. He says the application to get the federal grant money from the bipartisan infrastructure law only asks states to identify the number of orphan wells, the average cost per well to plug them, and the estimated unemployment levels in the oil and gas industry. He confirmed that measuring methane emissions from orphan wells is not part of the criteria the federal program is currently using when allocating the first round of funds.

While LDNR doesn’t have tools to measure methane emissions or spot them with optical imaging gear, regulators do watch out for methane leaks, and those findings do play into the site selection process of the OSR, Courreges explained.

“If we spot an obvious leak, we’re going to shut it down,” he said, explaining that they find them by listening for detectable noises and checking for signs of bubbling at well sites. “As far as something you’re going to need special detectors to pick up, no, we’re not set up for that. We’re set up to deal with immediate emerging risks.”

If ranking methane emissions is mandated, Courreges said LDNR wouldn’t be opposed to that, but the agency would probably need some input from state legislators to make that possible.

“I know in Appalachia that there’s a lot of interest in finding and plugging abandoned wells and orphan wells because they interfere with new drilling.”

– Amy Townsend-Small

Biven believes that resorting to smell-and-bubble tests to root out leaks is an inadequate way to monitor for methane, whether from orphan wells or active ones. Amy Townsend-Small, an associate professor of environmental science at the University of Cincinnati, agrees that the ability to identify methane emissions is critical if the money earmarked to plug orphan wells will make a meaningful impact.

“My research has shown that not all of abandoned wells are a source of methane and certainly not all are a significant source of methane,” Townsend-Small said on a call. “Most emissions come from a few sources.”

If site selection for plugging wells does not require identifying and quantifying methane emission, she fears taxpayer funds could be spent in a way that leads to more globe-warming emissions, instead of cutting them.

“I know in Appalachia that there’s a lot of interest in finding and plugging abandoned wells and orphan wells because they interfere with new drilling,” she said. So it is possible, she warned, that federal money — taxpayer money — could end up being used to plug orphan wells that would pave the way for new oil and gas wells in the area, which would lead to more climate pollution and benefit private companies.

Similarly, Biven pointed out that along the Gulf of Mexico some orphan wells could inevitably need to be plugged before companies such as ExxonMobil can develop a planned carbon capture and sequestration project. Biven and Townsend-Small say that without rules governing these funds, there would be no guardrail to stop private companies from steering regulators to plug wells to industry’s benefit, leaving the orphan well program open to abuse.

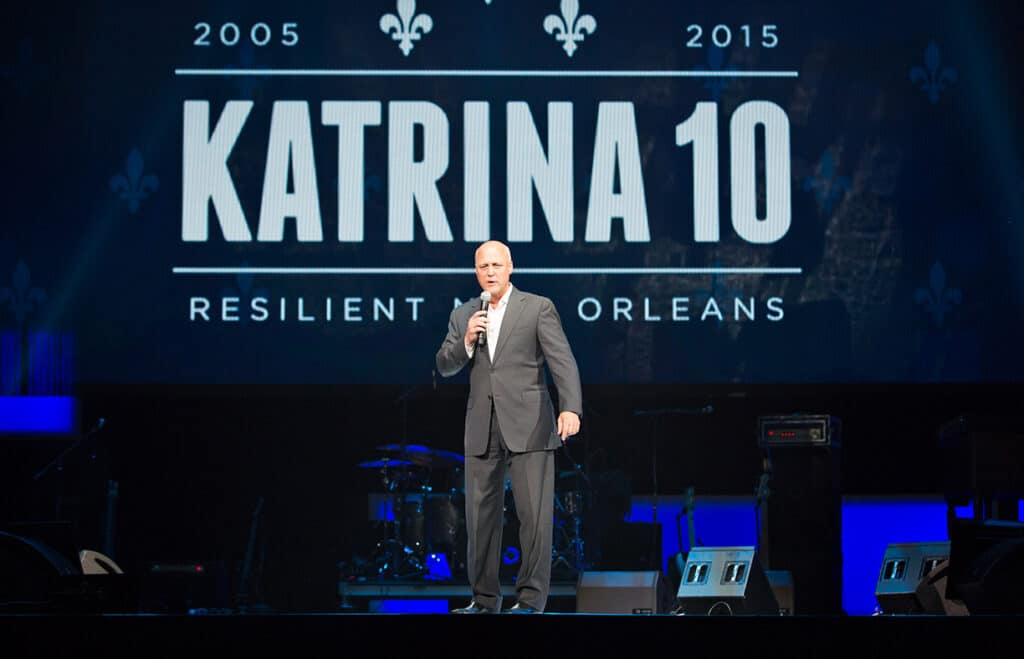

Is Mitch Landrieu up for the Job?

Mitch Landrieu, Biden’s infrastructure coordinator, could put in place these federal safeguards Biven is seeking. She thinks he has an opportunity to exert brave leadership, but questions whether he will.

Biden’s choice of Landrieu as the nation’s infrastructure czar dumbfounded many in New Orleans. While the president hailed Landrieu’s success in revitalizing the city after Hurricane Katrina, New Orleans failed to fully deal with many key infrastructure issues, to the point that some federal funds from FEMA languished so long the Department of Homeland Security directed FEMA to take them back.

In addition, some Louisiana-based environmental advocates also have expressed concerns about Landrieu having a conflict of interest. His sister Mary Landrieu is a former U.S. senator from Louisiana who has shown deep support for the oil and gas industry.

After she left office, Mary Landrieu became a lobbyist at Van Ness Feldman, which represents clients from the fossil fuel industry. In 2019, she sparked outrage when she spoke in support of the controversial Bayou Bridge pipeline at a public permit hearing. This January, she started serving on the leadership council for Natural Allies, a nonprofit coalition that advocates for natural gas to play a significant role in transitioning to a clean energy future, despite the clear links between the industry’s methane emissions and global warming. And among her list of fossil fuel industry clients are companies, including natural gas producer Venture Global, poised to seek permits for projects along the Gulf Coast where orphan wells will need to be cleaned up first.

I tried to contact Mitch Landrieu to ask if he had created rules to govern the bipartisan infrastructure law’s efforts to plug orphan wells and create jobs, but was unsuccessful. I asked the Department of the Interior the same questions and to be provided Landrieu’s contact information.

Tyler Cherry, the press secretary for the Department of the Interior, replied but didn’t provide Landrieu’s contact or offer a statement from him. Cherry simply wrote, “We don’t have anything to add on these questions for now, but we’re happy to stay in touch as the program continues to be implemented.”

Biven is hopeful that if she can meet with Landrieu and present the “Methane Memo,” offering guidance that could help ensure this public funding will be in line with Biden’s promise to tackle the climate crisis, then methane emissions can be tackled in a meaningful way.

“Landrieu can either punt to the state programs that helped create this crisis in partnership with the oil and gas industry; or he can lead and establish national standards such as actual methane measurement before and after plugging, or impose real regulatory reforms to prevent a new wave of orphaned wells, and build the foundation for a true national energy and methane mitigation policy,” Biven told me in an email. “Mitch Landrieu has the power and authority, but will he use it?”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts