The drizzle thickened over a working-class neighbourhood in northeast London on a cold June evening, as activist Delia Mattis stood waiting for friends, parka hood pulled up against the biting mist, clutching a sack full of campaign leaflets.

For the next two hours, the small group walked door to door distributing anti-waste incineration flyers in a community that was largely unaware it sits within the radius of a smokestack plume of a municipal waste incinerator, or MWI, one of five across the city.

Mattis, founder of Black Lives Matter Enfield, has become a central figure in a broad coalition of activists fighting to stop the planned replacement of an incinerator in the southeast corner of the borough.

She stands out for being one of the few people of colour within this predominantly white, middle class movement — a reflection of environmental activism in the UK more broadly.

“The movement isn’t diverse because Black people or people of colour don’t feel comfortable in white spaces,” said Mattis. It is getting better, she said, “but it’s a slow process.”

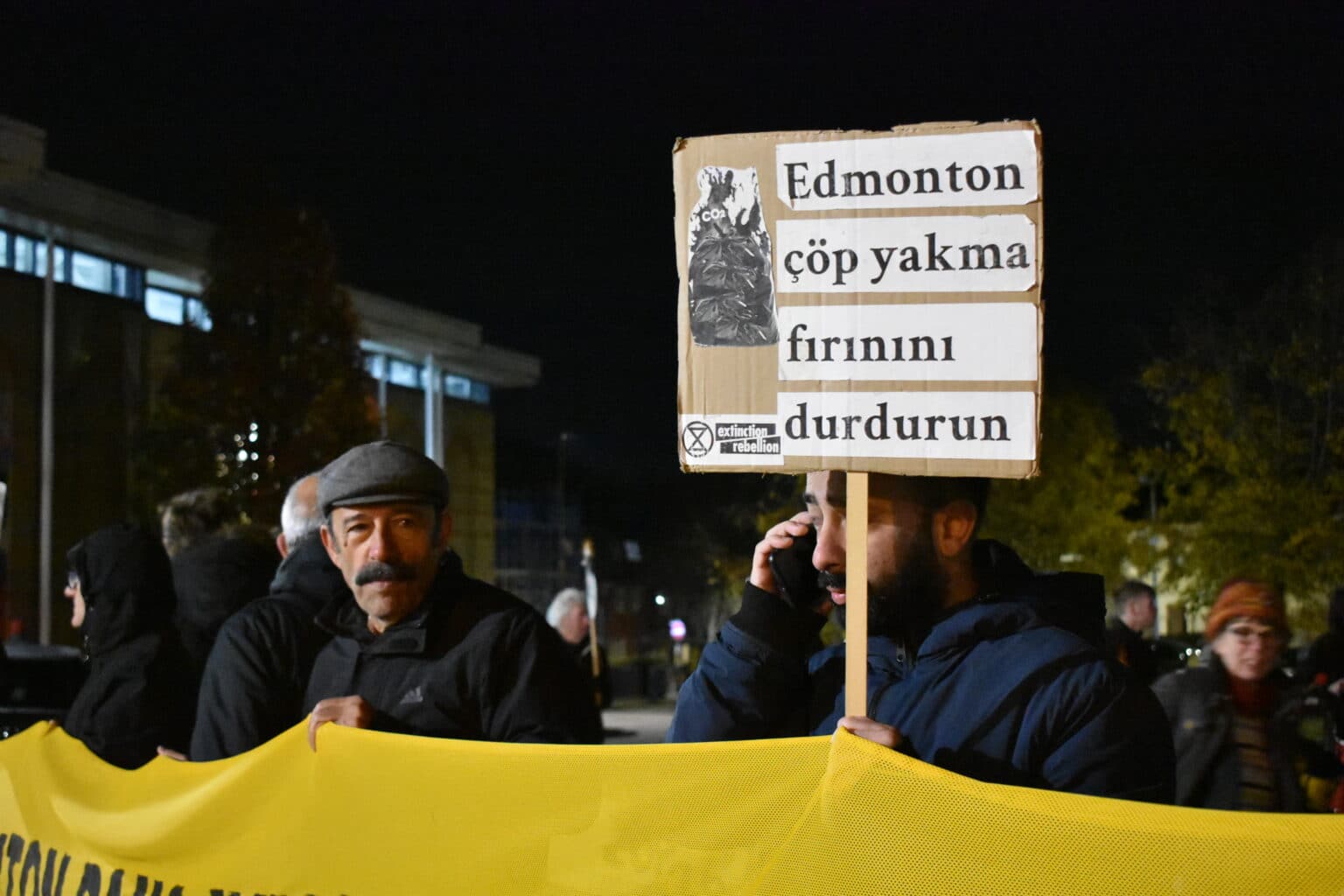

The incinerator, officially called the Edmonton EcoPark, is situated in an industrial pocket of Enfield that is among the 20 percent most deprived neighbourhoods in the UK with a population that is nearly 60 percent Black and minority ethnic, including a large Turkish-speaking community.

Promoting Environmental Justice

Carina Millstone, an environmental campaigner who spearheaded the creation of the Stop the Edmonton Incinerator Now (STEIN) coalition, of which BLM Enfield is a member, initially approached other local, largely white, environmental and civic organisations several years ago to raise awareness about pollutants from incineration.

Although air pollution from the incinerator could affect wealthier neighbourhoods miles away, Millstone learned that the most affected communities are Black and brown communities in Edmonton, spurring the recognition that as a group of white activists, “we could not progress the campaign with any legitimacy without really getting the people of Edmonton onboard.”

This acknowledgement is an early step in grappling with exclusion in environmental movements in the UK writ large. Nonetheless, the STEIN coalition itself is regarded by some as a small measure of success when it comes to inclusion in the environmental justice movement.

“I think it’s fair to say that the Edmonton campaign is one of the most ethnically diverse anti-incineration campaigns in the 20 years or so that I’ve been involved with the movement,” said Shlomo Dowen of the UK Without Incineration Network.

As a gathering of varied interests and actors, the coalition has organically begun to address at least some of what researchers have found for years: there are rigid mechanisms that act to reinforce divisions and boundaries in environmental movements, preventing active inclusion.

In addition to simply not feeling welcome in white spaces – digital and physical – as Delia Mattis said, a multitude of other factors have played a role in whether, and how, locals nearest the incinerator became involved in the campaign.

Language barriers, transience and a perceived lack of emotional connection to a neighbourhood, white privilege, immigrant status, lack of access to technology, and overly complicated campaign messaging are among them.

One of the key means of facilitating agency in underrepresented groups in Edmonton’s case was making sure campaign information was published in Turkish. Another was ensuring long-standing local civic organisations and trade unions knew about STEIN — a particular challenge during the pandemic, according to Asli Gul from Day-Mer, a decades-old organisation supporting north London’s Turkish and Kurdish residents, often in face-to-face settings.

The campaign has grown so much in the last three years that when a collection of activists from across the city, including Extinction Rebellion London, blocked entrances to the EcoPark on Monday, the group was more demographically representative of the Edmonton area than it otherwise would have been.

Millstone credits the degree of inclusion the coalition has achieved with “letting go and letting people take it on for whatever issue they are most interested in, so racial injustice or lack of community [consultation] … And letting other people take full credit for different bits and take it forward as they see fit.”

The Spectre of Landfill

On Thursday, the North London Waste Authority, the EcoPark’s governing body, is expected to vote on whether to award the construction contract for the incineration facility to Spanish multinational Acciona, the only bidder for the project. Work has already begun on a resource recovery facility at the site to process recycling.

Campaigners are calling for a pause-and-review of the plan based on a reassessment of value for public funding.

The NLWA argues that without the rebuild, the half a million tonnes of rubbish it processes each year will go to landfill – something the UK government began taxing in the late 1990s under EU regulations.

Subsequently, the number of MWIs in the UK mushroomed. A 2013 study found there were 25 MWIs able to produce energy operating in the UK. As of 2020, there were 54 operating with 16 more in late commissioning stages or under construction, according to consulting firm Tolvik. The energy recovered from burning waste is used to create electricity and heat that is sold to utility providers.

The spectre of landfill and its attendant methane production is something that makes some Edmonton residents reluctant supporters of the plan. Malcolm Prior, now in his late 80s, lives near the plant and worked at it for four years in the 1970s.

“I’m totally against landfill,” said Prior. “If you could avoid incineration, I’d say yes, do it tomorrow. But it’s not practical…. If everyone was like the campaigners, if everyone washed everything out, if everyone put plastics clean for recycling, there wouldn’t be a problem.”

In a statement to DeSmog, the NLWA said it is calling on the national government to mandate behavioural change to cut the volume of waste it has to deal with. Its requests include making recycling compulsory, banning single-use and nonrecyclable plastics, launching a deposit return scheme for plastic and glass bottles, holding manufacturers accountable for their packaging, and banning built-in obsolescence of devices to encourage repair and reuse.

The topic of environmental racism still looms large around Edmonton. When the existing plant was built in the late 1960s, the immediate population was still largely white, though it was shifting.

For Black activists it can seem as though the fight for environmental equality is under a two-pronged attack. On the one side there is the continued siting of a waste incinerator in a predominantly immigrant and Black neighbourhood. On the other is an environmental movement that has historically excluded them.

To beat the former, Delia Mattis said the climate justice movement needs to “amplify black voices and listen to what we have to say and make an effort to include us and our issues.”

“For my own capacity, I have to measure the amount of time I give to these predominantly middle-class white groups because I constantly have to remind them to raise the issue of environmental and institutional racism. It can be quite draining always having to be the one telling people to check their privilege.”

Parsons’ work has been published in Reuters, Malheur Enterprise, Anthropolitan, The Fourth Revolution, PBS NewsHour, and The Peregrine Dame.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts