Today’s eco-conscious consumer is no stranger to net zero pledges. There are “net zero” pensions, “net zero” fuels, even “net zero” mobile networks.

Thousands of companies have hitched themselves to the carbon-neutral bandwagon, from fossil fuel producers like BP and Shell, to other household names including United Airlines, Dell, Burger King, and Vodafone. Some companies say they’ll decarbonise by 2040, others as early as 2022.

But there are very real concerns about how these companies are going to meet their goals, with many relying on purchasing carbon credits generated by others’ efforts not to pollute, rather than reducing their own emissions as much or as fast as they can.

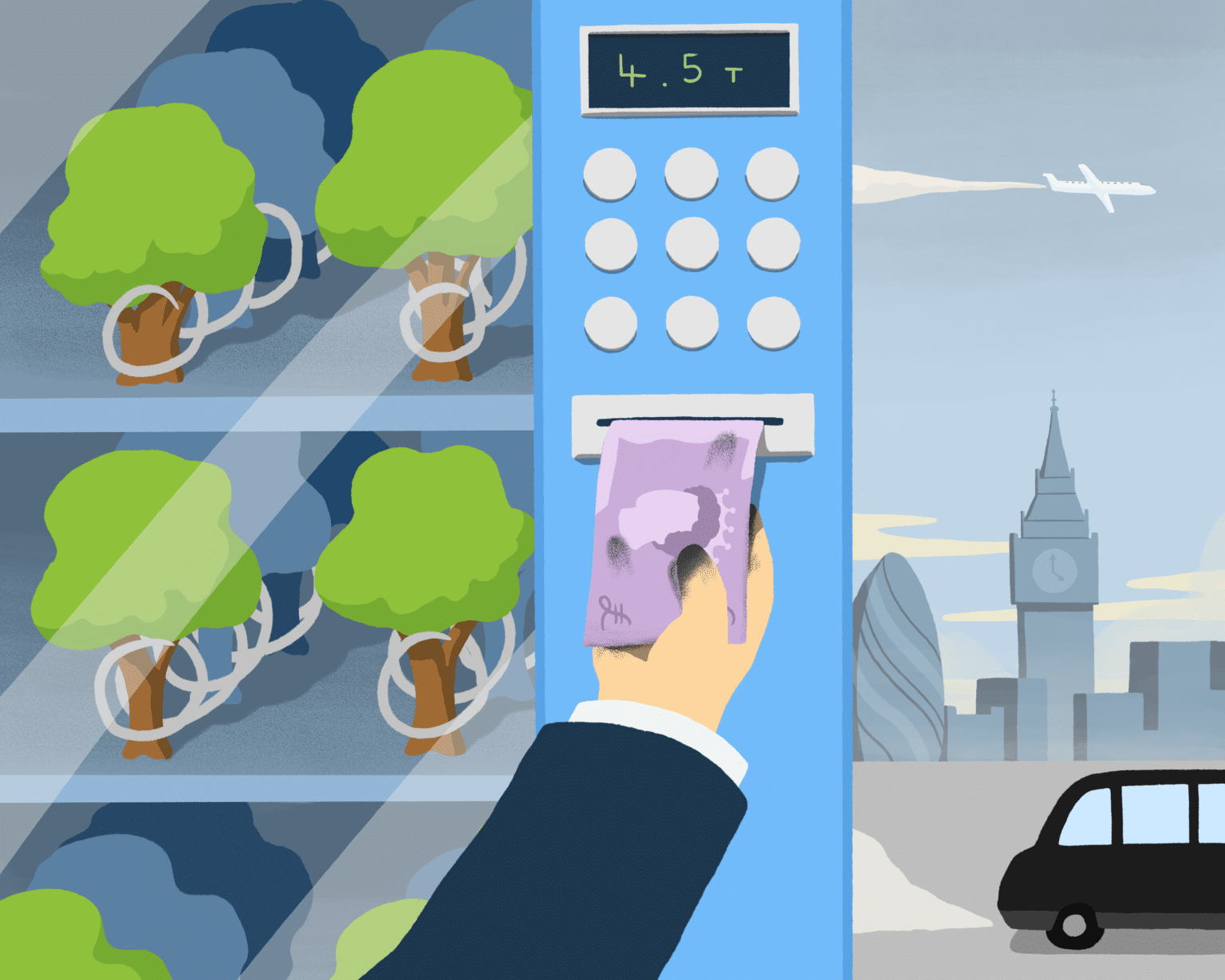

These actors are increasingly turning to voluntary carbon markets (VCMs) to offset their emissions. Unlike compliance carbon markets used by political entities like the EU, the UK or the state of California, VCMs allow companies and individuals to offset their greenhouse gas emissions on a voluntary basis outside of mandatory schemes.

In both types of market, one carbon credit is bought to “offset” one tonne of carbon dioxide equivalent, in theory capturing greenhouse gases in one location to avoid, remove or replace them in another. Compliance markets have long been plagued by concerns over their environmental effectiveness, and their use by companies and governments to “greenwash” – present an outwardly green image while continuing to pollute.

Voluntary markets have not fared much better, earning a reputation as the “Wild West” of offsetting due to their volatility and unpredictability. Green groups are concerned they offer a “get out of jail free card” for polluters, pushing focus on offsetting emissions rather than reducing them.

Yet the voluntary carbon markets model has recently enjoyed a new lease of life — and is being pushed hard by a particular set of actors, each with their own interest in seeing the offset credit market boom.

The Taskforce

At the heart of efforts to grow this controversial market is Mark Carney, former governor of the Bank of England, who last year launched the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM). This taskforce, set up with Bill Winters, chief executive of Standard Chartered bank, aims to create a “transparent, verifiable and robust” marketplace as a basis for this expansion.

And it’s already made waves. In the first eight months of this year, voluntary carbon markets saw a near-60 percent increase in value from last year, a growth attributed by market analyst EcoSystem Marketplace to corporate net zero ambition and growing interest in carbon markets to align with Paris Agreement targets of limiting global heating to 1.5C by the end of the century.

As well as providing a way to cut emissions, at least on paper, it’s also a market which has the potential to be very profitable. Carney has estimated it could be worth up to $100 billion a year by 2050, as businesses increasingly look to the marketplace to offset emissions that are harder to abate elsewhere, including those from cement, steel, container shipping and aviation.

But the taskforce’s initial recommendations have been met with hostility. Critics have warned that the VCM could become an international greenwashing exercise through polluters using cheap offsets to avoid cutting emissions.

The members of this taskforce, which include oil majors, banks and airlines, have also come under scrutiny, with campaigners questioning whether polluting corporations with a history of pursuing problematic offset projects are best placed to help decide the rules that regulate the industry.

‘Global Offsets Hub’

For the UK government, the Taskforce is crucial to the UK’s efforts to make the country “a global offsets hub”, providing banks and businesses with a route to aligning with the Paris Agreement.

The newly revamped VCM was referenced in the UK government’s long-awaited “Net Zero Strategy”, published just weeks before the COP26 climate summit. The 367-page document highlights aspirations for turning the UK into a leader in high-quality voluntary carbon markets – while noting they should be used in addition to, rather than as an alternative to, rapid decarbonisation.

“The government is closely following the important work of various sector-led initiatives including: the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets (TSVCM); the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative; UK VCM Forum; and, the Financing UK Nature Recovery coalition,” it adds.

Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak has said little publicly about the Treasury’s involvement in these initiatives, though both he and the Treasury have played some part in their creation.

Earlier this year, Sunak appointed Clara Furse, former London Stock Exchange Group chief executive, as chair of the Voluntary Carbon Markets Forum. This, according to its website, was designed to implement the framework recommended by Carney’s taskforce “to ensure UK-based firms and branches of global firms based in the UK can best promote the potential for scaling carbon markets”.

It also created the new independent governance body in September, which on Friday was named the Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Markets (IC-VCM). Furse took up a seat on the Senior Advisory Council of this new governance body, joining Mark Carney, Bill Winters and President and CEO of the Institute of International Finance (IIF), Tim Adams.

The Treasury also gave seed funding to the Green Finance Institute (GFI), a coalition of organisations from the financial sector. This is part of an alliance of UK environmental and business groups that launched the Financing UK Nature Recovery, an initiative to deliver “high-integrity markets for nature” and “mobilise capital towards nature-based solutions across the UK”.

The GFI is run by Environment Agency chair Emma Howard Boyd, a Global Ambassador for UN’s “Race to Zero” and “Race to Resilience” campaigns for COP26. The GFI has been appointed to lead the IC-VCM’s executive secretariat, which includes the British Standards Institute, the International Emissions Trading Association and the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. Also collaborating on Financing UK Nature Recovery is the Broadway Initiative, a coalition of business, environmental, professional and academic groups collaborating on net zero solutions, which counts the GFI as a partner.

The IC-VCM was created as independent from the Taskforce, and operates outside of government regulation. It is led by 22 representatives and supported by a host of experts and a coalition group of 250 organisations working to finalise the Core Carbon Principles, the long-awaited standards designed to help set a global benchmark for carbon credit quality.

According to the taskforce, these are “legal principles to guide the market and the criteria for carbon credit integrity”. These principles are expected to be rolled out gradually over the course of 2022, and only standard setters approved by the IC-VCM will be able to sign projects off as CCP-compliant

Like the TSVCM, the integrity council is formed by a mixture of banks, NGOs, standard setters and businesses. Jeff Swartz, director of climate at oil major BP, also has a seat at the table.

A spokesperson from BP said that the oil major aims to reach emissions reductions goals set for 2030 without relying on offsets, but does “support these offsets and are active in these markets”.

A Taskforce spokesperson told DeSmog the CCPs would be “based on projects that have a clear, measurable and direct impact in reducing carbon emissions and that also offer environmental and social integrity”.

“It will also take forward the Taskforce’s vision that organisations trading on the VCM should follow a clear hierarchy – to first reduce their own emissions, followed by regular and transparent reporting — and only then, trading any remaining emissions on the VCMs.”

Despite launching the private sector-led initiative, Carney has made clear he does not oppose government oversight, but believes that it is the responsibility of governments to step up their regulation of businesses to tackle the climate crisis. “We need clear, credible and predictable regulation from government,” he said back in July, adding that financial free markets would not reduce greenhouse gas emissions alone.

Management consultancy McKinsey has also been heavily involved in the taskforce, which it has provided with “knowledge and advisory support”.

McKinsey has recently been criticised by its own employees for its work with big polluters. The firm has a long history of consulting on forestry and offsetting schemes, facing regular criticism from campaigners for its analysis of the environmental impact of such measures.

Nonetheless, in January, McKinsey and the World Economic Forum (WEF) produced “Consultation: Nature and Net Zero”, a report which claimed to “build on” the work of the taskforce, and cited the rapid growth of natural climate solutions in the voluntary carbon markets. It has itself invested in the success of the VCM through the acquisition of the boutique sustainability firm Vivid Economics, which frequently collaborates on reports with the World Economic Forum.

Voluntary Carbon Markets and COP26

Once considered an unregulated outlier, voluntary carbon markets are featuring prominently at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow. And a set of politicos closely tied to the UK government will be busy promoting the market’s prospects as a climate solution at the meeting.

One event co-hosted by the UK government and Unilever explores the role of VCMs in “raising climate ambition” through addressing “issues of social and environmental integrity” and demonstrating “business ambition for investment in high quality Natural Climate Solutions”.

Rules around Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, one of the last undecided components of the “Paris rulebook” largely covering carbon markets, are expected to be advanced at COP26. According to the TSVCM’s “final report” in January 2021 the rules determined in the Article 6 negotiations, “will influence companies’ use of carbon credits.”

The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI) – a “multi-stakeholder platform” which featured in the Net Zero Strategy – has recently published guidance on developing “high integrity voluntary use of carbon credits”. According to its website, various members of its team will speak at a dozen COP26 events, including one on “high integrity VCMs”.

Taskforce co-founder Carney will be a major presence at the summit, as UN Special Envoy on Climate Action and Finance, chair of Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ), and finance advisor to UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

Johnson has also appointed a team of elite political players to work behind-the-scenes on the role of VCMs in the global climate negotiations. That team includes Nigel Topping, former CEO of nonprofit climate change coalition We Mean Business, as the UK’s High-Level Climate Champion for Climate Action, and Conservative MP for Arundel and the South Downs Andrew Griffith, as the UK’s Net Zero Business Champion.

Topping outlined the relationship between the three different roles in a session with the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Committee in June. “What we do is work to mobilise more ambition and action in support of the three pillars of the Paris Agreement: mitigation, so the Race to Zero; resilience, so the Race to Resilience; and private finance, working closely with Mark Carney’s team on the Glasgow Finance Alliance for Net Zero (GFANZ). All of those work very closely with Andrew and the COP26 Unit.”

GFANZ was set up earlier this year to help the global financial sector “transition to a net zero economy”. The group, which represents more than $70 trillion in assets, has reportedly struggled to persuade top banks to align their investments to the International Energy Agency’s roadmap on how to transition to a net zero energy system by 2050.

Despite the stated ambitions of these groups, campaigners remain sceptical about the role organisations and actors close to the government are playing in helping rejuvenate the voluntary carbon markets.

Louisa Casson, climate campaigner for Greenpeace UK, told DeSmog: “Major polluters are trying to find a way to avoid taking real action to tackle the climate emergency, by scaling up voluntary carbon markets that facilitate offsetting and make it easier for companies to announce ‘net zero’ climate pledges without doing the hard work of actually cutting their emissions.”

“Providing legitimacy to offsetting schemes that delay, undermine or distract from real decarbonisation is at odds with UK ministers’ goal to ‘keep 1.5C alive’ in Glasgow. Clubbing together with oil companies and big banks who want to use voluntary carbon markets to profit from business as usual is not credible climate action.”

The Banker’s Interest

These “big banks” are set to contribute significantly to the evolving voluntary carbon markets. Barclays, ICBC, HSBC, LLoyds, Santander, and NatWest are among the 29 banks within the 250 Taskforce members, as well as Commerzbank, Asian development bank and Rabobank.

This surge of interest can be explained through the market’s significance to the financial sector. The VCM offers banks a way to offset their Scope 3 emissions, which derive from a corporation’s upstream and downstream value chain – suppliers and distributors – as well as business travel, leased assets, and bank lending exposure.

The two founders of the Taskforce have been publicly confident about the integrity of the market. Winters has defended criticisms of the Taskforce, saying that a unified carbon market with high quality carbon credits and legal standards is integral to “allow participants to trade with confidence”. Carney, meanwhile, has claimed the VCM is a “necessary market in the transition to net zero” — while also saying it needs to be a $50-$100 billion market to work.

Axel Dalman, associate oil and gas analyst at not-for-profit think tank Carbon Tracker explained: “If you believe that carbon prices will rise in developed markets, and even the most dogmatically pro-fossil fuel company does, then it seems like a good investment to buy offsets, and there will certainly be demand for them.”

This could explain why the taskforce is sponsored by the International Institute for Finance (IIF) – a trade association for the global financial industry, whose members include banks such as HSBC, Barclays, Standard Chartered and Morgan Stanley. Tim Adams, IIF’s President, has been appointed member of the Senior Advisory Council on the Taskforce’s new governance body, and Sonja Gibbs, IIF’s chief executive officer and Managing Director has also joined its board of directors.

Banks have also begun developing their own infrastructure in response to the Taskforce’s needs. Standard Chartered has joined with Singapore-based DBS Bank and investment holding company Singapore Exchange to launch Climate Impact X, a global exchange and marketplace for carbon credits, by the end of the year. The exchange models its system on criteria set out by the taskforce, focusing initially on Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) projects, to “propel the development of new carbon credit projects worldwide”.

Chris Leeds, who is responsible for carbon markets trading strategy and product development for Standard Chartered and a member of Climate Impact X’s management team, will be among the board of directors on the IC-VCM.

The taskforce has also sparked a pilot voluntary carbon market, “Project Carbon”, a platform created by COP26 sponsor NatWest, along with Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, National Australia Bank and Itaú Unibanco in July. The platform, which enables buyers to trace which projects carbon credits come from, is aligned with the rules created by the taskforce, to “remove current barriers to voluntary carbon offset purchasing”.

While the financial sector’s interest in the voluntary carbon markets can be explained, the sheer level of interest shown by banks is unexpected. “If you look at the money that’s being traded in carbon markets compared to the volume and the money that’s being traded on the financial market and other commodities, it is just completely ridiculous,” said Gilles Dufrasne from not-for-profit association Carbon Market Watch.

“So, why would banks really want to be involved? The only logical explanation I see is that they expect a really strong growth and they do think that it’s going to become a profitable business.”

Setting Standards

A boom in the voluntary carbon markets could prove catastrophic for cutting carbon emissions if the credits traded aren’t sufficiently robust, however.

A recent report by Trove Research and UCL found that the voluntary carbon markets could be entirely supplied by “nature-based solutions” for the next ten years, due to their relatively low cost and availability. This, however, would put increased pressure on controversial carbon offset projects that rely on the avoidance or reduction of deforestation.

Standard-setters have responded to companies’ demand for credible offsets by creating rules to ensure these climate plans work. The Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) – a coalition between the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), the United Nations Global Compact, World Resources Institute (WRI) and WWF – is perhaps the most prominent of these, aiming to enable companies to set emission reduction targets in line with leading climate science.

The SBTi appears central to the Taskforce’s success, which has said it intends to use the initiative’s robust standards to decide which companies will be able to participate in the voluntary carbon markets. In a consultation report in May, the taskforce explained it was working with various stakeholders, including the SBTi and the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative, to develop a target validation criteria, which would allow companies to have their targets approved by the SBTi, as well as “user friendly guidance for setting net-zero targets.”

Last week, the corporate climate target setter introduced a higher bar for companies to follow. Under new rules, companies working with the initiative will now have to cut direct and supply chain emissions by at least 90 percent by 2050.

Speaking to DeSmog, Alberto Carrillo Pineda, co-founder of the SBTi, said that “companies cannot use carbon credits or other types of offsetting mechanisms to meet their targets – they have to reduce emissions.” Under the initiative, corporations would be unable to use carbon offsets for the first ten years of their plans, and thereafter only up to a maximum of 5-10 percent of the group’s total emissions.

Pineda added that he was unaware of the IC-VCM’s Core Carbon Principles, despite their expected significance for companies operating within the newly expanded voluntary carbon markets. He explained that, though the technical director of the SBTi Cynthia Cummis is a member of the advisory board, the SBTi “institutional relationship” with the new governance body.

The SBTi is also supported by Nigel Topping’s We Mean Business and the Climate Pledge Fund, a corporate venture capital fund that uses carbon offsets in its approach to reaching net zero. The Climate Pledge Fund has put up $2 billion to invest in sustainable technologies and market infrastructure to ensure high-quality projects.

The SBTi shares a significant common ally with the Taskforce through the World Resources Institute, one of the 13 founding members of the IC-VCM. In particular, Frances Seymour, a distinguished fellow of the World Resources Institute, is central to developing the IC-VCM’s plans.

Seymour has conducted research and writing on forest and governance issues and advised WRI leadership on major initiatives including Global Forest Watch, the Global Restoration Initiative, the Food and Land Use Coalition, and Cities4Forests. She also sits on the expert advisory group of the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative.

In a recent blog post, Seymour discussed the “alphabet soup” of initiatives that had sprung up around the voluntary carbon market, as well as the corporate buyers seeking expert advice regarding what kinds of credits they should purchase. “If we get this right, this new private sector demand could finally help realize the promise of REDD+ market-based finance at scale,” she wrote.

Seymour is also the founder of the international initiative, Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART), which works with the Lowering Emissions by Accelerating Forest Finance (LEAF) initiative. This was launched by the UK, Norway and the United States to work with businesses such as Amazon, Airbnb, Bayer, McKinsey, Nestlé, and Unilever to provide $1 billion to protect tropical forests.

Dufrasne, of Carbon Market Watch, is concerned that issues around dodgy carbon accounting have not been settled.

“We need to channel finance to forest conservation on a large scale, and we cannot use this as an excuse to continue polluting,” he told environmental news platform Mongabay after the LEAF initiative was announced.

“An emission reduction should only be counted once,” Dufrasne added, “and the new coalition should more clearly explain how they will ensure this. The risk of double counting the reductions, once by the country where they take place and once by the company buying the credits, remains.”

While the SBTi sets the standards for companies, credit verifiers like Verra and Gold Standard provide accreditation by which credits can be traded. Though these varifiers were established to ensure quality in the industry, a recent investigation by Unearthed found that Verra, which is represented on the IC-VCM’s board of directors, was “overhauling its methodologies to help the market scale-up” and that its projects could not produce enough carbon savings to justify their claims.

Verra, however, disagrees, stating that its standards to date have been able to meet the challenges presented by the rapid growth of voluntary carbon markets. “The largest challenge that we have faced is optimising our internal operations to handle the influx of requests to register projects and to issue credits, as our paramount concern has always been, and will continue to be, the integrity of what we certify,” a spokesperson said.

Though Verra has publicly commented that it welcomes the work of the TSVCM, it did not agree the Taskforce would be crucial in determining whether carbon credits represent good value for the climate.

The current promotion of voluntary carbon markets as part of the solution to climate change was allowing governments, polluters and banks most responsible for global heating a free pass, Rachel Rose Jackson, from non-profit campaign group Corporate Accountability, told DeSmog.

The UK wasn’t the only country “driving this agenda” Jackson said, but “a prominent driver through their COP26 presidency as well as the Mark Carney-led Taskforce – an initiative that some of the world’s largest polluters have helped to shape”.

“What’s most problematic is that hundreds of billions of dollars are being spent not to rapidly and justly transition economies to renewable energies, keep fossil fuels in the ground, and implement real solutions today, but instead to advance a self-serving agenda that relies on risky schemes and dangerous, unproven technologies- putting millions of lives at risk,” she added.

A government spokesperson said: “Voluntary carbon markets are an important element of climate change mitigation, when strict environmental and social safeguards are met. Many developing countries plan to use the carbon market, and the UK is working on laying the foundations for a credible and responsible global carbon trading system.”

All other organisations and individuals referenced in the piece have been contacted for comment, and had not responded by the point of publication.

Editing by Phoebe Cooke and Rich Collett-White. Additional research by Michaela Herrmann.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts