In February last year, the head of a leading global meat industry body gave a “pep talk” to his colleagues at an Australian agriculture conference.

“It’s a recurring theme that somehow the livestock sector and eating meat is detrimental to the environment, that it is a serious negative in terms of the climate change discussions,” Hsin Huang, Secretary General of the International Meat Secretariat (IMS), told his audience. But the sector, he insisted, could be the “heroes in this discussion” if it wanted to.

“We cannot continue business as we have done in the past,” he went on. “If we are not proactive in helping to convince the public and policymakers in particular, who have an impact on our activities – if we are not successful in convincing them of the benefits that we bring to the table, then we will be relegated to has-beens.”

Huang’s speech points to an industry nervous about its role in a carbon-constrained future. In the face of mounting evidence of the livestock industry’s climate impacts and a growing array of meat alternatives, the sector has developed a multi-pronged PR strategy that seeks to legitimise not only the industry’s current activities but also its plans to scale up production — despite clear warnings from scientists that this could scupper efforts to meet climate targets.

DeSmog conducted a five-month investigation into the meat industry’s PR and lobbying, reviewing hundreds of documents and statements by companies and trade associations. Our research shows how the industry seeks to portray itself as a climate leader by:

- Downplaying the impact of livestock farming on the climate;

- Casting doubt on the efficacy of alternatives to meat to combat climate change;

- Promoting the health benefits of meat while overlooking the industry’s environmental footprint;

- Exaggerating the potential of agricultural innovations to reduce the livestock industry’s ecological impact.

This article was published alongside new additions to DeSmog’s Agribusiness Database, where you can find a record of companies and organisations’ current messaging on climate change, lobbying around climate action, and histories of climate science denial.

The Climate Impact of Meat

Today’s meat industry is dominated by a few multinational giants, including JBS, Tyson Foods, Vion, and Danish Crown, with access to markets across the world. In step with rising global demand, meat production has more than quadrupled in the past sixty years.

Despite this tremendous growth, forecasts indicate that the world is still far from reaching “peak meat”. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which represents many of the world’s biggest economies, and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) predict that global meat production will continue to rise in the coming decade as incomes increase in developing countries.

But that trend sets the world on a collision course with the climate targets laid out in the Paris Agreement. A study published in Science last year found that even if emissions from fossil fuels ceased right away, projected eating habits would make it impossible to keep global average temperature rises to 1.5C.

And a more recent study from New York University (NYU) looked at how meat companies could blow through the climate targets of their countries of origin. The European Union’s largest pork producer Danish Crown, for example, is set to consume 42 percent of Denmark’s emissions budget under the Paris Agreement by 2030 in a business-as-usual scenario.

It’s in this context that meat companies have ramped up their efforts to market their products as climate-friendly, says Kristine Clement, campaign lead of agriculture and forests at Greenpeace Denmark. The industry wants to continue its rapid growth, but is terrified that “politicians will stand up and say, ‘No, we can’t continue this endless production of meat,’” she explains.

‘New Narrative’

Meat producers casting themselves in an environmentally friendly light isn’t a new phenomenon. But increased public pressure for companies to act in a climate-conscious way has caused a step-change in the industry’s PR efforts.

According to Jennifer Jacquet, associate professor of environmental studies at NYU, and a co-author of the study looking at meat companies’ carbon footprints, the first high-profile revelation that the livestock sector was operating beyond ecological limits and having significant negative environmental impacts came in a 2006 FAO report titled Livestock’s Long Shadow.

Since then, meat industry players have shifted from emphasising the supposed sustainability of organically-produced meat to painting meat as an answer to ecological challenges like climate change.

At a virtual conference in March, for instance, the Animal Agriculture Alliance (AAA), a US-based industry group, announced plans to “change the narrative and position animal agriculture as a solution to reducing our environmental footprint and improving our planet for generations to come.”

For Jacquet, though, such promises are little more than reputation management. “That’s what these people in these positions are paid to do”, she says, referring to trade associations such as the IMS and AAA. She adds:

“They’re paid to comfort us. They’re paid to get us to not think hard and deeply about the industry. They’re paid to assuage our worries. And they’re paid to tell regulators: ‘Don’t worry, we’ll self-regulate. We’ll do a good job. You don’t need to worry about us. We are good actors.’”

Jennifer Jacquet, Associate Professor of Environmental Studies

Meat companies themselves have also stepped up their climate-friendly advertising. Danish Crown relaunched its website in 2019, pledging to set “a new direction towards a more sustainable future” with a “new brand and narrative” designed to “make it clearer to customers and consumers that Danish Crown has started this transformation.”

In 2020, the company ran a large-scale campaign across TV, radio, newspapers, and billboards, insisting that its pigs were “more climate-friendly than you think.” The same year, it put stickers on its pork products, describing pigs slaughtered by the company as “climate-controlled.”

Greenpeace Denmark’s Clement argues terms like “climate-friendly” or “climate-controlled” may mislead consumers into thinking that pork produces few emissions, or even that it’s beneficial to the climate.

Danish Crown told Greenpeace that it stopped using the “climate-friendly” line after criticism from consumer organisations. The company has never announced the decision publicly, though, a move Clement says is unacceptable: “They have spent millions of kroner to get this message out in people’s faces, and they have not communicated anywhere that they have accepted the critique and stopped using it.”

The company apparently has no plans, however, to withdraw the “climate-controlled” labelling, recently claiming that a voluntary certification program it runs for its suppliers and which forms the basis of the labelling is “reasonably robust”.

The company’s refusal to withdraw the second campaign and publicly retract claims made during the first has so angered environmental groups in Denmark that in June, three filed the country’s first climate lawsuit over Danish Crown’s advertising slogans.

According to Rune-Christoffer Dragsdahl from the Vegetarian Society of Denmark, one of the plaintiffs, even if the industry manages to cut emissions as much as it claims, pork would “still be much more climate-damaging than plant-based alternatives”, and it’s therefore misleading to describe it as climate-friendly. Dragsdahl hopes the lawsuit will deter other meat companies from spreading similar narratives. “Someone has to draw a line in the sand before this gets out of hand and just becomes completely confusing for consumers,” he says.

But Danish Crown is standing by the campaign. The company did not respond to DeSmog’s requests to comment for this story, but its communications director Astrid Gade Nielsen told Danish media: “We believe that our campaign is a strong program based on what our farmers do on the farms.”

Campaigns run by the AAA and Danish Crown are just two examples of the way in which the meat industry is increasingly turning to a playbook long used by other polluting sectors such as Big Oil and pesticide manufacturers, with the campaigns ultimately causing “confusion and delay,” NYU’s Jacquet argues.

Meat Industry Playbook

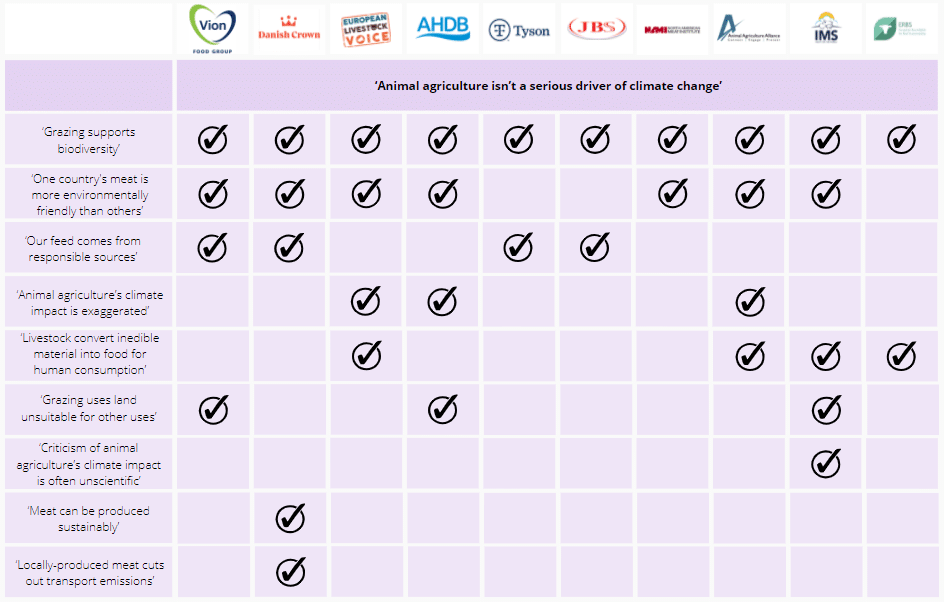

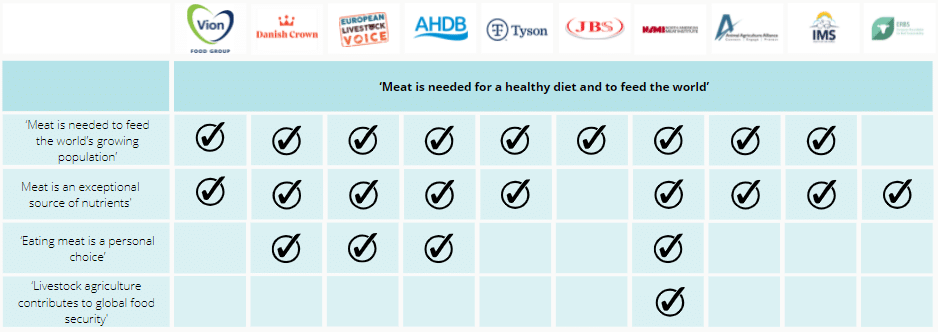

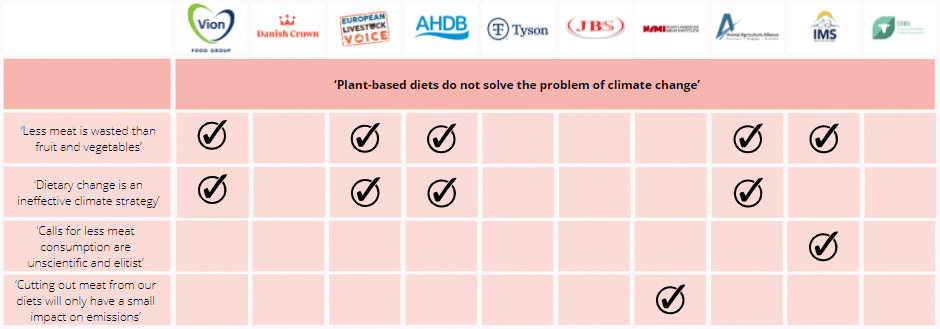

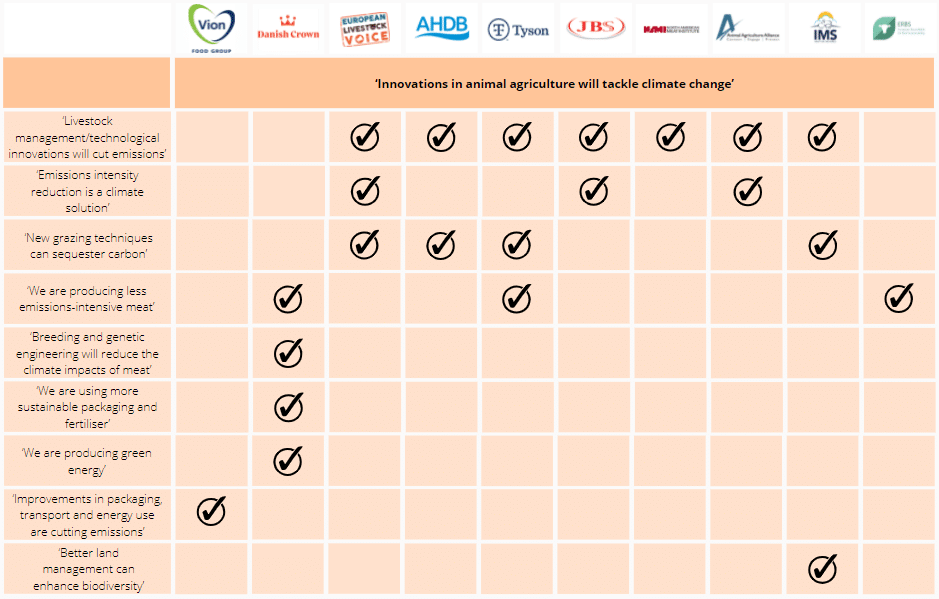

Through a major review of the PR materials of 10 key meat industry organisations, DeSmog has identified a number of tactics being employed by industry players again and again.

All organisations in this investigation were contacted by DeSmog for comment. IMS and JBS responded and you can find their full comments here. AHDB responded to technical questions, and you can find its answers in its profile.

All other organisations did not respond to DeSmog’s requests to comment.

Underreporting Emissions

A popular means by which producers play down the impacts of their products is to narrow the scope of the activities they count towards their emissions.

The AAA calls U.S. animal agriculture “a model for the rest of the world,” claiming that the livestock sector is only responsible for four percent of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. But the Environmental Protection Agency estimate on which this is based does not factor in land use when calculating agriculture’s share of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions — an omission that significantly decreases the figure.

Land use and land-use change are so-called Scope 3 emissions: indirect emissions that include, in the case of livestock farming, cattle grazing and crop cultivation for animal feed production. Studies show these activities represent the majority of the sector’s emissions, yet many meat companies exclude them when calculating their carbon footprint.

The AAA did not respond when DeSmog asked about its emissions claim.

Not all meat companies avoid talking about their Scope 3 emissions, however. JBS has recently announced a target of achieving net-zero emissions by 2040 that includes indirect emissions. It told DeSmog: “As a global company with complex value chains, we understand the challenge of establishing Scope 3 emission reduction targets.”

“While this is a challenge that companies of a similar size also face throughout our industry and other important sectors, we are taking decisive steps to set credible Scope 3 emissions targets,” it explained, adding that JBS works with the voluntary Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) to set its climate targets.

“As a leading global food company, we recognize the importance of reducing our environmental impact to combat climate change,” it told DeSmog.

The non-profit GRAIN, which advocates for small-scale farming, and the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP), a US-based sustainable farming research organisation, have however found that meat giants JBS, Tyson Foods, Danish Crown, and Vion have all, at one time or another, hugely under-reported their annual emissions.

The discrepancy between the numbers is all the more striking considering that the organisations calculated emissions using the FAO’s Global Livestock Environment Emissions Assessment Model (GLEAM), which was shaped in part by the FAO’s Livestock Environmental Assessment and Performance (LEAP) Partnership, a multi-stakeholder initiative that includes meat and dairy industry groups.

Companies also use different emissions estimates to back up different claims, DeSmog’s investigation finds.

As part of its “pigs are more climate-friendly than you think” campaign, Danish Crown quoted a study from Aarhus University, claiming that one kilo of Danish pork produced only 2.8kg of carbon dioxide-equivalent in 2016, down from 3.8kg eight years before. But in an opinion piece published in 2020 in the newspaper Altinget, its CEO Jais Valeur referred to a World Resources Institute (WRI) study concluding that one kilo of Danish pork produces 10.8kg of carbon dioxide emissions.

The study was commissioned by Landbrug & Fødevarer, an organisation representing the Danish agriculture sector, to compare livestock emissions between countries, finding Denmark was among the lowest-emitting for pork and dairy.

The difference between the emissions estimates again resulted from different calculation models. Unlike Aarhus University, the WRI took land-use-change and the carbon opportunity costs associated with meat production into account. So while Danish pork producers generally don’t use the higher WRI estimate, Greenpeace’s Clement says that “they still use the report to say that ‘we are amongst the best in the world.’”

The IMS’ Huang defended its stance on the emissions on the livestock sector when contacted by DeSmog, saying it “does not make specific (quantitative) claims about emissions for meat companies or any particular organization — the main role of IMS is to promote sustainability, not certify or police it. Our commitment for actions to reduce climate impact do not rely on predictions from any particular model, but rather on concrete actions that can be applied in real life.”

Meat to Feed the World

Major producers also work to justify the industry’s expansion by portraying meat as indispensable to feeding the growing global population. But critics question how necessary that expansion is, and point out that it could be done in different, more climate-friendly ways.

Four companies analysed by DeSmog, JBS, Tyson, Vion, and Danish Crown, claim to be contributing to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal of achieving Zero Hunger by 2030.

But the UN does not advocate for the expansion of the kind of large-scale, industrial meat production the companies conduct, arguing in a recent discussion paper that the emphasis should instead be on supporting small-scale farmers, whose livelihoods could be threatened by the expansion of multinational meat giants.

That hasn’t stopped the industry presenting itself as a solution to world hunger, however.

In a video released in 2020, Vion’s CEO Ronald Lotgerink stated that “in 2050, we have to feed 10 billion mouths. All those people have the right to safe, quality food.”

Danish Crown is similarly blunt, declaring that the climate impact of meat “does not mean that the company will be producing less meat”, because in 2050 “there will be approximately 10 billion mouths to feed.”

Likewise, the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), an arm’s-length body connected to the UK’s Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs, calls the UK “one of the most sustainable places in the world to produce beef and lamb” and claims that setting any limit on livestock production would be “a misguided and meaningless” climate mitigation strategy since livestock farmers “produce vital, nourishing food for a growing population.”

The UN describes the health and environmental implications of consuming animal products as “complex” and works to ensure that low-income groups have access to animal-based foods but argues that other, wealthier populations need to eat less of them. The FAO declares that it is particularly committed to supporting small-scale livestock farmers in developing countries—an agricultural group that has shrunk dramatically in countries like the U.S., where giant corporations now dominate the market.

When contacted by DeSmog, the IMS’s Huang pointed to the same UN paper to defend the industry’s position, stating that “there is a substantial body of evidence that meat and livestock sourced food will be needed to feed the growing population,” especially in poor and developing countries. Reducing the consumption of animal-sourced foods in “some segments of the population in richer countries would be desirable,” Huang added.

“We do agree with FAO on the need to better support small-scale livestock farmers in developing countries,” he said, adding “more effort is clearly needed here.”

Dismissing Dietary Change

While the industry promotes meat as a solution to world hunger, it has simultaneously sought to undermine the concept that significantly reducing meat in diets, or replacing animal products with non-meat alternatives, is an effective emissions reduction strategy.

Meat producers’ fears about the rise of alternatives is understandable. The availability of plant-based products has surged in recent years, and various types of cultured meat are under development. According to the consultancy AT Kearney, meat alternatives could swallow up more than half of the global meat supply by 2040 — a forecast that aligns with the planetary health diet advocated by the EAT-Lancet commission, an interdisciplinary scientific committee, which recommends global consumption of red meat to halve by 2050.

Confronted with these new rivals, the meat industry argues that reduced meat consumption would do little to tackle climate change.

For instance, Vion claims that “eating less meat will not necessarily contribute to more sustainability,” while the North American Meat Institute (NAMI), a US industry group, and the European Livestock Voice (ELV), an EU-level campaign launched by livestock interest groups in 2019, both argue that removing animal products from people’s diets would only reduce US emissions by 2.6 percent.

All three groups back up their claims with a 2017 study by researchers at Virginia Tech’s Department of Animal and Poultry Science and the US Dairy Forage Research Center that has been criticised by researchers from multiple fields for using what they consider an unrealistic scenario design.

Other meat groups have dismissed the findings of the EAT-Lancet report. The AAA warned in a statement released after the report’s publication that drastically limiting meat and dairy consumption would have “serious, negative consequences” for planetary and human health, with the IMS referring to the study as “elitist,” “biased,” and “not scientifically well-founded.”

When contacted by DeSmog, the IMS replied that they were “far from alone” in voicing this type of criticism but none of the critics it named supported the organisation’s claim that increased meat production is needed to feed the world's growing population. Vion, NAMI and ELV did not respond to DeSmog’s requests to comment on this story.

The way in which the industry has gone on the defensive is hardly surprising, says NYU’s Jacquet. The sector is being challenged on its environmental and health impacts, as well as food security, which “suggests eating meat compromises food security for others”, she explains. And it’s therefore to be expected that the industry will resort to “rhetorical devices” that are “defensive against all those lines of attack.”

Technological Fixes to Save the World

Alongside undermining the alternatives, the meat industry has also been eager to paint a futuristic, technologically advanced picture to justify its continued growth. Like the fossil fuel and pesticides industries, it regularly points to innovations that it says will soon lower the sector’s emissions drastically. Some go as far as claiming these will enable the industry to go fully carbon neutral.

JBS’s CEO Gilberto Tomazoni announced last year that the company had already taken “a giant step” towards a more sustainable production process thanks to an array of technologies and that it had “a huge capacity to produce more without devastating anything.” In addition, meat industry groups such as the AAA and AHDB promote various climate innovations, ranging from anaerobic digesters and precision feed management to new slurry and manure management technologies, which they say significantly reduce the industry’s climate footprint.

But environmental campaigners have criticised manure management technologies such as anaerobic digesters, which they argue help large-scale factory farms to continue operating “under the guise of mitigating climate change,” pointing out that methane-capture technologies fail to address the majority of the industry’s emissions. Precision agriculture has also been promoted by agrichemical industries as a climate change solution, despite questions about the efficacy of the techniques in tackling climate impacts.

When asked about these criticisms, the IMS’s Hsin Huang said there was “no single silver bullet solution” and that the industry would therefore “need a variety of technologies.” Livestock producers were undertaking “considerable efforts”, he said, to improve how animals are fed, bred, and managed to produce more meat from fewer animals.

But the Vegetarian Society of Denmark's Dragsdahl says there is another negative effect of relying on such technology. Denmark’s agricultural sector is heavily indebted and investments in technologies such as biogas digesters can push livestock producers even further into the mire, he argues.

For Dragsdahl, adding new technological innovations to the country’s industrial agriculture sector is the equivalent of “throwing bad money after bad money” because the technologies do not address the fundamental problems caused by the sector. “We just have too many animals,” Dragsdahl says, referring to Denmark’s colossal livestock population. “The sector invests a lot of money in these technologies instead of just investing the money in a transition to something that creates many fewer problems for our country.”

A key pillar of this supposedly climate-positive future for the industry is the concept of regenerative agriculture — an approach also heavily promoted by pesticides producers.

Regenerative agriculture seeks to restore natural habitats and reverse climate change by restoring soil health and improving its ability to store carbon. Pioneered by groups including small-scale indigenous and Black farming communities in the US, the concept has come to play a curious role in the meat industry PR playbook. According to its advocates, the fact that the soil where cows and other ruminant animals graze can sequester carbon has the potential to transform the livestock sector into a climate hero, rather than the villain many environmental campaigners consider it.

For example, the AHDB claims that improved grazing management “can sequester tons of atmospheric carbon in soils,” while the ELV repeats claims made by US beef industry group National Cattlemen’s Beef Association President Jerry Bohn that improved ranchland and pasture management can “more than offset” cattle methane emissions.

Researchers are unconvinced, however, with Sonali McDermid, associate professor of environmental studies at NYU, who co-authored the industry carbon footprint paper alongside Jacquet, arguing it is far from certain that the approach can neutralise industrial meat production’s enormous climate impacts. While there is a lot of “positive press” around the idea, “evidence is still limited that it can scale to meaningfully sequester carbon,” she explains.

A Winning Playbook?

So far, the meat industry seems to be having considerable success with its climate-friendly communications strategy.

This could be, in part, because it is benefitting from a general lack of media scrutiny. According to an analysis by researchers from Oxford University, Stanford University, and the State University of New York, elite media outlets in the US and UK rarely reported the link between the consumption of animal-based foods and climate-change between 2006 and 2018. The study’s authors observed that when the media did report on the topic, it put a much higher emphasis on the impact of individual consumer choices than the responsibility of large-scale meat corporations such as Tyson.

This failure to connect the issues can have knock-on effects on consumer behaviour. According to Greenpeace’s Clement, meat companies like Danish Crown benefit from a lack of public understanding about environmental issues to spread their messaging. The company conducted an opinion poll before launching its 2020 pork campaign, showing that only one out of five Danes find it easy to make sustainable choices when they shop. This fact, Clement says, allows the company's communications to “misinform consumers”. Danish Crown did not respond to the allegation when approached by DeSmog.

Like the tobacco and fossil fuel industries before it, the meat industry is engaged in a PR battle, with journalists struggling to mediate.

Jan Dutkiewicz, a Policy Fellow at Harvard Law School researching large-scale conventional meat production, is frustrated by media coverage that aids the meat industry by uncritically reporting unverified claims about its climate impact — a situation reminiscent of mistakes made when communicating the fundamentals of climate science:

“If you have virtual consensus on one side and a few people over here, many of whom received funding from the meat industry, that should be reported. It shouldn’t be seen as two equal interlocutors presenting equally valid opposing opinions.”

Jan Dutkiewicz, Policy Fellow, Harvard Law School

When presented with these criticisms of the meat industry’s climate communications, the IMS’s Huang defended the livestock sector’s role in a carbon-constrained future by saying it does “not claim to be perfect” and that it recognises the “need to improve” and “find more or better solutions.”

He added: “Constructive criticism is welcome, and indeed necessary in order to advance. Moreover, as with other sectors, any assessment must take an integrated and holistic view as the hallmark of achieving sustainability: that means looking at the environmental (including impacts on climate change), socio-economic (livelihoods), and nutrition (health) impacts, in specific country and regional contexts. Trade-offs are inevitably involved but searching for best (or even win-win-win) solutions, informed by actual practices in countries, is key to the IMS stance, based on robust evidence.”

“Our strong belief, based on the science, is that livestock and animal source food benefits people and the planet: livestock is a valuable contribution to sustainability,” he said.

But as it stands, there is a gap between what the meat industry is reported to be doing and what it is actually doing to address its environmental impact, Jacquet argues. For her, the amount of positive media attention companies like JBS and Tyson receive just for making commitments to reach net-zero emissions is “astonishing”.

“Those words don’t seem to have associated actions as yet,” she says. “We all have to demand more than just words. We need action as well."

This investigation was covered by the Independent

Edited by Rich Collett-White and Mat Hope.

Please note this work and all related parts of this investigation are © DeSmog UK Ltd 2021. These materials are not licensed under Creative Commons.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts