In a recent post, I sought to explain, from a motivational standpoint, why it is that climate deniers can reject the overwhelming evidence that humans are causing the Earth to warm. We already have reason to think their motivations are not scientific, e.g., not driven by a quest to understand the truth about the atmosphere. Rather, climate denial seems closely linked to conservative and libertarian politics—the sense that the free market simply couldn’t have made such a mess of things; and the deep distrust of large scale government solutions that involve intervening in the economy.

We also know that the selective attention to biased information sources plays an important role. For instance, watching Fox News correlates closely with being less trusting of climate scientists, and with being misinformed about whether scientist think the Earth is warming.

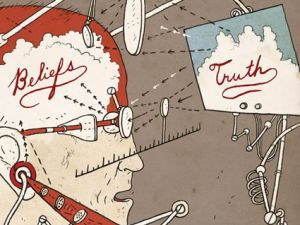

But there’s another key factor. And it happens to be the subject of a major feature story of mine that just came out in Mother Jones magazine, entitled “The Science of Why We Don’t Believe Science.” Here, I discuss a phenomenon referred to in the political psychology literature as “motivated reasoning”:

The theory of motivated reasoning builds on a key insight of modern neuroscience (PDF): Reasoning is actually suffused with emotion (or what researchers often call “affect”). Not only are the two inseparable, but our positive or negative feelings about people, things, and ideas arise much more rapidly than our conscious thoughts, in a matter of milliseconds—fast enough to detect with an EEG device, but long before we’re aware of it. That shouldn’t be surprising: Evolution required us to react very quickly to stimuli in our environment. It’s a “basic human survival skill,” explains political scientist Arthur Lupia of the University of Michigan. We push threatening information away; we pull friendly information close. We apply fight-or-flight reflexes not only to predators, but to data itself.

We’re not driven only by emotions, of course—we also reason, deliberate. But reasoning comes later, works slower—and even then, it doesn’t take place in an emotional vacuum. Rather, our quick-fire emotions can set us on a course of thinking that’s highly biased, especially on topics we care a great deal about.

Consider a person who has heard about a scientific discovery that deeply challenges her belief in divine creation—a new hominid, say, that confirms our evolutionary origins. What happens next, explains political scientist Charles Taber of Stony Brook University, is a subconscious negative response to the new information—and that response, in turn, guides the type of memories and associations formed in the conscious mind. “They retrieve thoughts that are consistent with their previous beliefs,” says Taber, “and that will lead them to build an argument and challenge what they’re hearing.”

In other words, when we think we’re reasoning, we may instead be rationalizing. Or to use an analogy offered by University of Virginia psychologist Jonathan Haidt: We may think we’re being scientists, but we’re actually being lawyers (PDF). Our “reasoning” is a means to a predetermined end—winning our “case”—and is shot through with biases. They include “confirmation bias,” in which we give greater heed to evidence and arguments that bolster our beliefs, and “disconfirmation bias,” in which we expend disproportionate energy trying to debunk or refute views and arguments that we find uncongenial.

Yes, that’s right: The mental processes that lead to climate denial, and to cleverly arguing back against any new study that comes out supporting the scientific consensus, may be largely automatic and rooted in subconscious emotional responses, which in turn call to mind, from memory, a battery of standard arguments—and which also motivate new ones. The emotions would be generated by one’s strong political perspective—and, notably, intelligence is not necessarily any protection against motivated reasoning. Quite the contrary:

Republicans who think they understand the global warming issue best are least concerned about it; and among Republicans and those with higher levels of distrust of science in general, learning more about the issue doesn’t increase one’s concern about it. What’s going on here? Well, according to Charles Taber and Milton Lodge of Stony Brook, one insidious aspect of motivated reasoning is that political sophisticates are prone to be more biased than those who know less about the issues. “People who have a dislike of some policy—for example, abortion—if they’re unsophisticated they can just reject it out of hand,” says Lodge. “But if they’re sophisticated, they can go one step further and start coming up with counterarguments.” These individuals are just as emotionally driven and biased as the rest of us, but they’re able to generate more and better reasons to explain why they’re right—and so their minds become harder to change.

Clearly this applies to the rejection of climate science—but motivated reasoning can occur on any topic where there are strong beliefs and motivations, and even (or perhaps especially) in one’s personal relationships. No one is immune. In the article, I further use motivated reasoning to help explain diverse phenomena ranging from vaccine denial to the persistence of the belief that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction.

But if this is really what’s going on—climate change is an emotional issue, e.g., highly politicized, and that’s driving the generation of skeptic arguments—then it follows that refuting skeptics scientifically might not always work. Rather, we may need to depolarize the issue, come up with solutions that they can accept—and get everybody to calm down.

There’s much more about motivated reasoning, and the implications, at Mother Jones. From now on, because I think there’s real explanatory power here, I’ll be including references to motivated reasoning in much that I write about climate change denial.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts