Earlier this year, I grew uncomfortable with attempts to link the massive tornado destruction that we saw in the U.S. to climate change. As I explained then—based on an interview with Harold Brooks, one of our top experts on tornadoes and climate—the evidence just doesn’t support this assertion. We can’t show that tornadoes have gone up, or gotten worse. Nor can we show that the theory or models predict that they should in a warming world.

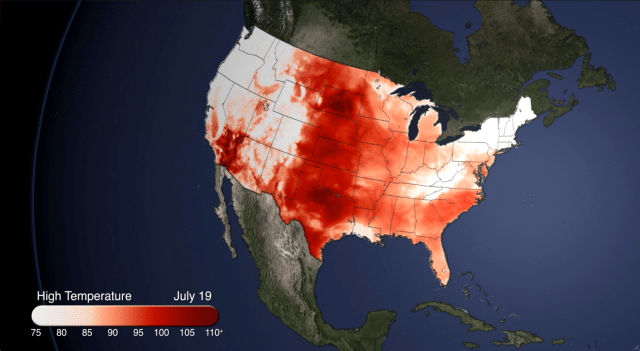

However, we’ve just experienced a staggering U.S. heat wave (visual here), and that makes it seriously time to talk about the link to climate change, and not shut up any time soon.

First, let’s review the heat wave, thanks to the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang:

Nationally, 1,966 daily high maximum temperature records have been broken or tied so far this month (through July 23). Sixty-six of those records were all-time maximum temperature records.More impressive, however, are the figures for highest minimum temperature records. Because of the extremely high humidity levels during this heat wave, a whopping 4,376 record highest minimum temperature records were broken or tied through July 23. Of those minimum temperature records, 158 were all-time records.

While the tornado-global warming linkage is among the hardest of cases to make, the heat wave linkage is among the easiest. It is just fricken obvious that on a warming planet, the chance of greater heat extremes goes up, because the dice are loaded in their favor. NOAA itself reports that overall, the U.S. was .5 degrees Celsius hotter from 1981-2010 than it was from 1971-2000, leading the agency to talk about a “new normal” for U.S. temperature.

Similarly, the IPCC says of U.S. heatwaves unequivocally:

Severe heatwaves, characterised by stagnant, warm air masses and consecutive nights with high minimum temperatures, will intensify in magnitude and duration over the portions of the U.S. and Canada where they already occur (high confidence) (Cheng et al., 2005). Late in the century, Chicago is projected to experience 25% more frequent heatwaves annually (using the PCM AOGCM with a business-as-usual emissions scenario, for the period 2080 to 2099) (Meehl and Tebaldi, 2004), and the projected number of heatwave days in Los Angeles increases from 12 to 44-95 (based on PCM and HadCM3 for the A1FI and B1 scenarios, for the 2070 to 2099 period) (Hayhoe et al., 2004).

Then there’s NASA climatologist Gavin Schmidt, who told Media Matters that it’s

…very probable that any particular heat wave happening now will be shown to have become more likely because of global warming…Of all the different extreme events that can happen, the partial attribution of heat waves to ongoing climate change is one of the easier connections.

What this means is that now—not during the May peak of tornado season—is the time to once again try to rally the public to care about climate change.

The seasonality of public concern is annoying, or even downright irrational, but it’s also very real. Just look at the public opinion data from Yale and George Mason: When people are asked either about whether “The record heat waves last summer in the United States strengthened my belief that global warming is occurring” or whether “The record snowstorms this winter in the eastern United States make me question whether global warming is occurring,” their answer is, basically, “Yes.” Actually, to be precise, 54 percent somewhat or strongly agree with the former, while 47 percent somewhat or strongly agree with the latter—and they’re surely not all the same people. Still, this just hints at the pliability of public opinion on this issue when the weather changes.

That’s why summer is always the time to talk to the public about global warming, and we need to recognize that other parts of the year probably aren’t as good.

And lest you think this too obvious to bear mentioning, never forget: In 2009, the IPCC held an absolutely critical meeting in a snowy December in Copenhagen.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts