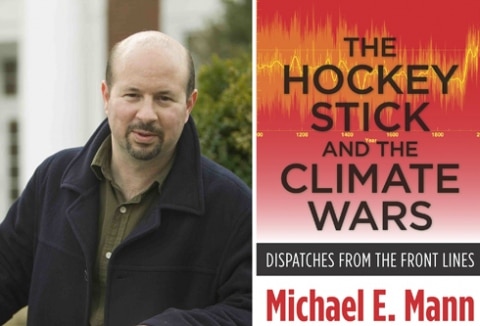

This is a review of The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches From the Front Lines, by Michael Mann.

I first became familiar with the name Michael Mann in the year 2003. I was working on what would become my book The Republican War on Science, and had learned of two related events: The controversy over the Soon and Baliunas paper in Climate Research, purporting to refute Mann and his colleagues’ famous 1998 “hockey stick” studyJames Inhofe, at which Mann testified. Inhofe tried to wheel out the Soon and Baliunas work as if they’d dealt some sort of killer blow against climate science. In fact, just before the hearing, several editors of Climate Research had resigned over the paper.

I went on to stand up for Mann, and his work, in Republican War. Little did I know, at the time, that he himself would become the leading defender of his scientific field against political attacks.

Recently, Mann came out with a new book about his travails entitled The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars: Dispatches From the Front Lines, detailing his decade long battle against political attacks and misrepresentations. The response has been all too predictable. For months, conservatives have been giving it one star reviews on Amazon.com, some of which suggest that they probably haven’t read it.

What is most fascinating to me is that the science the right is attacking Mann over—principally, the 1998 hockey stick study and its 1999 extension, as prominently exhibited in 2001 by the IPCC—is relatively old news. Indeed, and as Mann himself explains in the book, “attacks against the hockey stick…were not really about the work itself.” That work has been supported by other researchers—there is now a veritable “hockey team,” Mann notes—and anyways, the case for human caused global warming never depended on the validity of the hockey stick alone. It was always just one part of a far broader body of evidence.

Thus, conservatives who fixated on Mann, and continue to do so, tell us through their own actions that this is not really about scientific inquiry at all. If it was, then they’d be doing something quite different from giving Mann one star Amazon reviews.

But of course, climate researchers have been making observations like these for years. It hasn’t mattered nearly as much as it should, though, because they’ve often lacked the communication skills to get their point across. If anything, their scientific training has tended to hobble them in a brass knuckles fight such as this one. And that, to me, is where Mann’s new book matters the most: It shows that he has developed the communication skills to match his unquestionable scientific talent–and moreover, that he has done so because the right forced him to.

That’s why Mann is such an inspiring example for all who care about the climate issue—and why his book is required reading. From the early “hockey stick” battles all the way up through “ClimateGate” and the Ken Cuccinelli inquiry, Mann didn’t give an inch. He didn’t back down; to the contrary, he showed what toughness actually means. And in the process, from the founding of RealClimate.org in 2004 up through the publication of this book, he evolved into a passionate communicator and advocate. Having had him on my podcast Point of Inquiry and heard him lecture, I can assure you that many scientists should take a lesson from him.

Through all this, Mann emerged as a charismatic example of what we should all strive for in the face of ideological adversity and unfair attacks. Mann himself has a powerful analogy for all of this in the book, one that shows just how much he has developed as a communicator and an advocate. He calls it the “Serengeti Strategy,” based on what he saw on a vacation in Africa:

Among the most striking and curious scenes I saw that day were groups of zebras standing back to back, forming a continuous wall of vertical stripes. “Why do they do this?” an IPCC colleague asked the tour guide. “To confuse the lions,” he explained. Predators, in what I call the “Serengeti strategy,” look for the most vulnerable animals at the edge of a herd. But they have difficulty picking out an individual zebra to attack when it is seamlessly incorporated into the larger group, lost in this case in a continuous wall of stripes. Only later would I understand the profound lesson this scene from nature had to offer me and my fellow climate scientists in the years to come.

To be sure, the book is not simply about how Mann was forced to fight back against misrepresentations, and even congressional and legal inquiries. It’s also his personal story. He started out as a math geek trying to program a computer to play tic-tac-toe, like in the movie War Games (ah, the Eighties!). He ended up pursuing paleoclimatology out of intellectual interest and fascination; he never imagined he would end up as much a political combatant as a researcher.

Despite my praise for Mann and his book—and I even gave it a cover blurb—I do have some differences with him. For instance, I think that here and in his public comments, Mann tends to focus too heavily on the idea that resistance to climate science, and his research, is corporate driven. Or as he puts it in the book: “well organized, well-funded, and orchestrated.” In contrast, I have increasingly come to think it is primarily ideological—driven by libertarian individualism, and those who embrace this view and its associated emotions—and the corporate connection is secondary (though often real). I thus think that focusing on it too much misleads us as to the nature of the opposition, which has grown so ideological at this point–and so driven by gut emotion–that it does the traditionally pragmatic business community no favors. If anything, it is out of synch with its own presumptive allies.

But this difference doesn’t matter when it comes to defending scientific reality. There, I stand with Mann, because he taught me through his own example how to do so. And you should as well.

How? Start by buying his book

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts