The next time I gas up my car, I will have a lot to think about after watching the new documentary film, Delta Boys, now available for digital download release starting today at Sundance and iTunes, and on DVD at Amazon.com.

The film chronicles the plight of the people of the Niger Delta in Nigeria, the fifth largest supplier of oil to the United States. Despite the wealth generated by this oil extraction, the majority of Niger Deltans live on less than a dollar a day and lack even basic public health and sanitation services.

Nigeria suffers the equivalent of an Exxon Valdez oil spill every year, as it has each of the last 50 years of oil exploitation. “The wealth underground is out of all proportion with the poverty on the surface,” in the words of The New York Times.

The film brings to light the Niger Delta people’s ongoing struggles against multinational oil corporations and one of Africa’s most corrupt governments. While most of the revenue from oil development flows to the Nigerian government in the form of royalties, in the rural Delta villages where the drilling actually takes place, there are no water or sewage systems, no schools, no hospitals, no adequate roads, and no real job opportunities outside of joining one of the rebel militias.

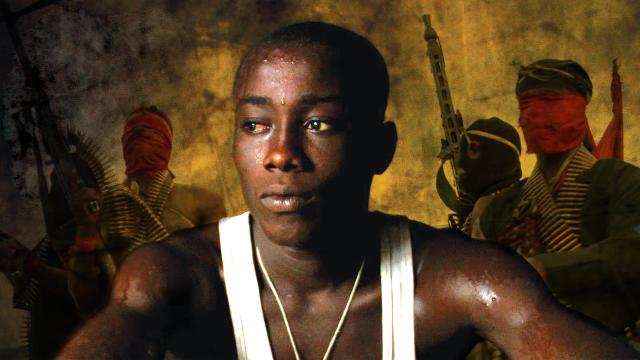

Meet the Delta Boys – armed rebels who zoom around the Delta in high-speed motor boats, sabotaging oil infrastructure, blackmailing the oil companies, kidnapping workers, and tapping into their pipelines to feed a lucrative but dangerous black market in oil they claim is rightfully theirs.

Nigeria has expelled many journalists for investigating the nation’s oily conflict zones. But that didn’t deter a Brooklyn-based filmmaker from defying the odds to capture the intriguing story of the Delta Boys.

I recently spoke with Andrew Berends, the courageous filmmaker behind Delta Boys, about what drives him to such dangerous places to document the stories of the people living through such hellish conditions.

Listening to his accounts of making two wartime documentaries in Iraq, it’s clear that he’s no stranger to danger. He’s willing to risk his own hide in these places in order “to close the distance” between Americans and their overseas sources of oil.

Berends: “It’s such an important story. It’s about where our oil comes from. It’s about the environment. It’s not just a local story in Nigeria. To me, it has global importance. The conflict there is largely driven by the fact that the world, and the West in particular, is so dependent on oil, and we have this desire for oil to flow as cheaply as possible.

And it’s not just for gasoline for our cars, but everything we consume, we’re so dependent on oil. But the result of this dependency, while at the same time we’re not wanting to pay any more than we absolutely have to, is that people suffer in places like the Niger Delta. It’s a direct result of our addiction to this resource that they happen to have. “

Berends says the harsh reality is that there is plenty of money flowing to the local governments in the Delta, but it isn’t being appropriated for much-needed infrastructural development, education and job creation. Instead, it is enriching a few opportunists and thuggish mafia dons while the villagers struggle to survive.

Berends: “Corruption is rife in the federal government, the local government, among the militants, it’s a big problem. The only place where I don’t observe some degree of corruption is in the villages. Not to say that everything’s perfect there, but it’s the only place where you feel you’re a little more grounded in decent humanity.”

Delta Boys includes many interviews with villagers who rely on the fish, forests and fruit trees for subsistence. In what I found to be one of the most powerful moments in the film, Berends speaks with a fisherman who is unwilling to join the rebels, or to steal or cheat to make a living. “I will only struggle,” he says, as the camera points to the oil-contaminated waters the man tosses his fishing hooks into every day.

The fisherman seems rather lonely in his moral objection to the militias and gangs. Of course, that could be because the militias have slaughtered innocent fishermen just like him, accusing them of being informants for the government or oil companies, despite zero evidence. The rebel camps make the neighboring villagers nervous and vulnerable. When the government decides to battle the militants, the villagers suffer most in the crossfire. They become refugees in their own backyards.

Meanwhile, the rebel lifestyle looks comparatively comfortable, with 3 square meals a day, cigarettes and plentiful booze provided by the leaders. “It beats the prison yard,” says Chima, one of the central characters from the camp run by the “Godfather,” Ateke Tom, who rules his rebel army with an iron fist.

Most of the boys seem happy enough, at least until several are viciously flogged for failing to adhere to their camp’s militant discipline. A whole-body caning is the consequence for falling asleep through patrol duty, or firing a weapon in camp.

That’s not the only source of tension. Since the militant camps are comprised of individuals from vastly different villages, religions and cultures, there isn’t a true cohesion. They hail from broken families, with little or no education, and essentially no opportunities to earn an honest living. So they’re drawn to the rebel camps, where they get high and pretend to be powerful, even though they live essentially in captivity given the strict, cult-like rules. One scene depicts the consequences of a quarrel between two boys from different backgrounds – they’re forced to fight each other until they’re exhausted.

“I have friends, but I have no friends. We are just like gangsters, ” Chima says at one point, noting that they are only “brothers in business.”

Watching Delta Boys, you’d be forgiven for feeling empathetic to the rebel cause, at least for a minute. The militants claim they’re witnessing a theft of their local resources, which they feel should be fueling their own local economies, not those of the corrupt Nigerian government and multinational oil companies. But the rebel leaders are also rather despicable characters, thriving on greed and power.

As I watched the film, I couldn’t help but see some parallels between what’s happening in Nigeria and what’s happening here in North America. Granted, the problems are far more acute in the Niger Delta, but the symptoms of petropolitics are all around us.

Anybody heard of disaffected aboriginal and rural communities in North America angry that government has failed to secure their fair share of resource wealth, or to safeguard their health and environment from fossil fuel disasters? Wouldn’t that sound familiar to, say, the Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation, the Yinka Dene Alliance, or other communities battling against the expansion of Alberta’s tar sands?

How about the peaceful Keystone XL protesters in Texas who’ve been pepper-sprayed, tased, and otherwise bullied by TransCanada’s hired police thugs? Or perhaps the residents of fracked Pennsylvania who’ve endured the gas fracking industry’s use of military psychological warfare tactics to divide their communities?

Our collective thirst for oil and gas is turning Canada and the United States into petrostates beholden to the interests of multinational oil corporations. Although not as acute as in Nigeria, we see the threats to the environment, public health, human rights and community resilience right here at home.

While the film does an incredible job of providing a window into the life of the Niger Delta militants and the surrounding villagers, there is no word from the real villains, the multinational oil companies like ExxonMobil and Royal Dutch Shell who pollute the Delta with zero accountability to its inhabitants.

The lack of industry perspective wasn’t an oversight on Berends’ part. Although his primary focus was filming life in the rebel camps, he did attempt to interview company officials, and even hoped to spend time on a drilling rig to provide a look at the life of the workers. Needless to say, the companies weren’t interested in accommodating such a spotlight on their activities, nor was the Nigerian government. “They don’t want this story told.”

They nearly succeeded.

After filming for eight months in the Niger Delta, Berends was captured by the Nigerian Army, detained by the government for ten days, accused of espionage and expelled from the country. His friends in the film community rallied grassroots supporters and assistance from 10 U.S. Senators to pressure the Nigerian government to release him. While he says he never felt personally threatened as far as his physical well-being, the Nigerian government clearly hoped to chill his resolve to complete the film.

And if he weren’t so dedicated to the project, it might have worked. It wasn’t an easy task to pull off. While Berends received some financial support from the Sundance Institute Documentary Film Program, Cinereach and The Gucci Tribeca Documentary Fund, he still had to raise over $16,000 through Kickstarter to help fund the final stages of the film’s production. And, in a sign of how difficult it is to make important documentaries like this compared to fluffy entertainment films, Berends still had to dig deep into his own savings to make Delta Boys a reality.

I’m glad he did, and every American (or anyone else) who watches Delta Boys will see how much hard work went into making it.

Berends: “Will the film make an inch of difference? I don’t know. But if it helps make people a bit more aware about our oil addiction, and about how people treat each other, hopefully we’ll be more thoughtful about our energy use.”

Delta Boys is available for digital download release starting today at Sundance and iTunes, and on DVD at Amazon.com. Look for it on Netflix, Hulu and elsewhere in the new year.

Image Credits: Andrew Berends

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts