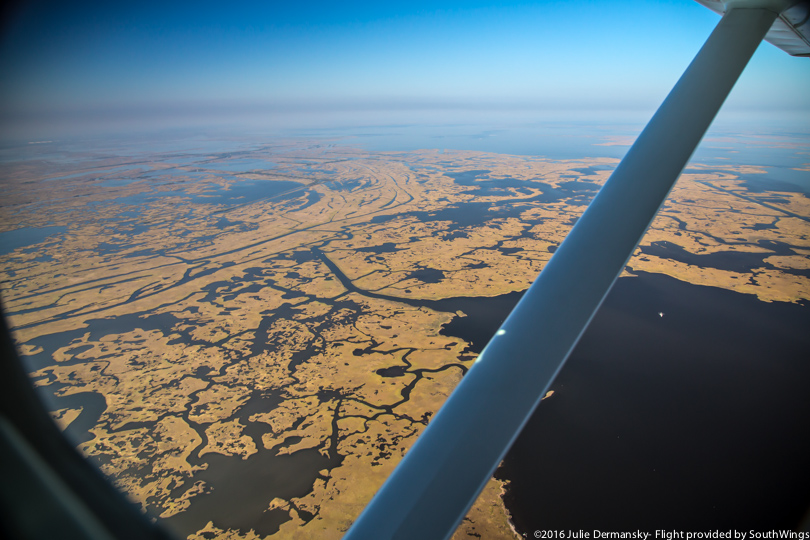

The Louisiana coast loses a football field’s worth of land every 38 minutes. This staggering rate of land loss has been brought on by climate change and coastal erosion accelerated by human activities, including water diversion projects and damage done by the oil and gas industry.

It is also a problem that is best seen from the sky. Thanks to the nonprofit conservation organization SouthWings, I was able to photograph the state’s troubled coast for DeSmog during a flight on November 15, 2016.

“Flying out along the Louisiana coast and seeing the tattered wetlands from above with your own eyes make the scale of the threat posed by coastal land loss feel strikingly real and immediate,” Meredith Dowling, SouthWings associate executive director, told me while discussing the group’s work.

The organization offers flights, piloted by volunteers, with the goal of expanding the public’s understanding of the biodiversity and ecosystems of the American Southeast. “To have a pilot point at a map that shows where land should be and look down and see only water, that sticks with you,” she said.

Oil and gas industry site near the mouth of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana.

Dowling is based in New Orleans. For her, the state’s land loss is personal.

“Coastal land loss and climate change threaten the future of coastal Louisiana and all of us who call this place home,” she said. “Having independent eyes monitoring our critically important ecosystems and reporting bad actors to regulators helps protect us all from those who would illegally pollute our land and waterways.”

During my flight, I photographed active and abandoned oil and gas industry sites that have been named in lawsuits, filed by parish governments, which are making their way through the court system.

Plaquemines, Jefferson, Vermilion, Cameron, and St. Bernard Parishes have filed multiple suits against oil and gas companies which operate, or used to operate, in their parishes.

The parishes allege that the companies did not comply with rules spelled out in the permits that allowed them to work in the wetlands, or operated without permits at all, hastening coastal erosion. The permits require companies to restore the areas they impacted to the original condition when work is complete — a requirement overlooked by the industry for years. The lawsuits aim to provide some of the funds needed to repair and restore the coast.

Oil and gas industry site in Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. The state is losing 100 yards of coastal land to erosion every 38 minutes, with oil and gas industry practices contributing to this problem.

Oil and gas industry site near the mouth of the Mississippi River in Plaquemines Parish.

Former Republican Governor Bobby Jindal’s administration tried to squash the parish lawsuits, but current Democratic Governor John Bel Edwards’ administration supports them.

Gov. Edwards has alerted coastal parish governments that if they do not sue oil and gas companies for environmental impacts to their parishes, the state may do so on their behalf.

Aerial view of Terrebonne Parish, one of the Louisiana parishes that didn’t opt to sue the oil and gas industry for environmental damages from past practices.

The straight lines of human activity still cross the wetlands of Terrebonne Parish, where they are visible from the sky.

But despite Gov. Edwards’ attempts to hold industry accountable for the harm already caused to the coast, he is simultaneously welcoming new fossil fuel energy developments along that same coast and lavishing the industry with tax incentives.

On December 21 he announced that Venture Global LNG will be building a liquified natural gas (LNG) facility, which will also export LNG, in Plaquemines Parish. The $8.5 billion LNG complex will be able to export 20 million metric tons of LNG per year and is expected to offer 250 jobs with an average yearly salary of $70,000.

But Anne Rolfes, founding director of the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, thinks that the state should be considering more than just the LNG facility’s ability to create decent-paying jobs. Her organization advocates for the state to move away from the fossil fuel industry and instead develop sustainable energy projects.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” Rolfes told TV station WDSU, “To be on the one hand grappling with coastal destruction, and the other hand preparing to build a huge facility on that very same coast.”

Similarly, the Obama administration recently gave mixed signals on climate change and fossil fuel development.

On December 22, it released a draft climate science report, which maintains that climate change is primarily caused by humans releasing greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. On the same day, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management announced that the agency will offer “more than 48 million acres offshore Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama for oil and gas exploration and development, in a lease sale that will include all available unleashed areas in the Central Planning Area.”

Rolfes isn’t counting on the state’s congressional delegation or the incoming Trump administration to protect Louisiana.

“One thing we can see in this post-election world is that people are upset and are in the streets,“ Rolfes wrote in a press release after Donald Trump’s victory in the presidential election. “We will harness this energy for real action on climate change, on accidents, for an end to drilling in our Gulf of Mexico ― for all the things we have to do if we want to leave our children a planet they can live on.”

The photos here are a reminder of Louisiana’s predicament: An area the size of at least three football fields vanished from the Louisiana coastline while I wrote these words.

As for the Trump administration soon taking the helm, Dowling said SouthWings remains undaunted. “We have seen politics threaten to undermine environmental protections before, and we will persevere.”

Golden Meadow, Louisiana, in Lafourche Parish, one of the coastal parishes that opted not to sue the oil and gas industry for past practices that failed to restore coastal wetlands.

A natural gas flare is visible at an oil and gas facility in Plaquemines Parish.

Infrastructure dots the waters and disappearing coastal land of Plaquemines Parish.

Industrial buildings line the fragile coast of Plaquemines Parish.

The oil and gas industry has long been building on the coastal land of Plaquemines Parish, though that activity has contributed to the disappearance of that fragile land due to coastal erosion.

Plaquemines Parish is one of the Louisiana parishes suing the oil and gas industry for failing to restore coastal wetlands affected by the industry’s practices, a requirement long overlooked.

An aerial view of Lafourche Parish reveals the disappearing remains of its coastal lands. This parish decided not to participate in the lawsuits against the oil and gas industry for failing to restore coastal wetlands, a practice which is helping shrink the remaining coastal lands.

Island Road leading from Isle de Jean Charles to Pointe au Chien, in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana.

Main Image: Golden Meadow, Louisiana, in Lafourche Parish.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts