Scattered throughout Coos County, situated on Oregon’s southern coast, are signs reading “Save Coos Jobs, Vote No on County Measure 6-162.” The signs were put there by Save Coos Jobs, a political action committee (PAC) with more than $358,500 in funding from Canadian-based energy company Veresen’s Jordan Cove Energy Project and other natural gas interests.

Measure 6-162 will go to vote in a May 16 special election. If passed, it would block what could become Oregon’s top greenhouse gas emitter: Canadian energy company Veresen’s proposed multi-billion dollar Jordan Cove Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) export facility and its associated 232 mile Pacific Connector gas pipeline.

Though the funding to defeat the “Coos County Right to Sustainable Energy Future Ordinance” is pouring in from out-of-state contributors and a PAC whose treasurer works for a government relations firm in Portland, Oregon, opponents have centered campaign messaging around fears that the measure could endanger “our community’s” economic future.

“If passed by voters,” Save Coos Jobs claims, “[the measure] would send a signal to the rest of Oregon and the world that Coos County is essentially ‘closed for business.’”

According to Jordan Cove LNG, the project would create 175 permant jobs. Environmental impact statements have predicted slightly fewer, at 150, along with an estimated 2,000 temporary construction jobs.

Hans Radtke, a natural resource economist who has served on the Oregon governor’s Council of Economic Advisors since 1993, told DeSmog:

“These construction jobs tend to be very specialized — people move with the jobs. So you bring in people who have just been in the Dakotas. When you see these jobs come in, you see license plates from other states.”

While he acknowledged that the LNG project will support some local jobs such as in restaurants, he questioned the extent. “How much of that money is actually going to stay [in Coos County]?” Radtke asked. The permanent jobs created, he said, would be highly automated and consist substantially of security jobs.

“I would not put my money on this project being built,” he added.

From Project Denied to Trump White House Boost

The fight over the terminal has been an ongoing saga in the Northwest.

When it was first proposed, private property owners who refused to give up their land became a first line of defense. In response, the project sued to overturn Oregon’s “landowner signature requirement,” which requires projects using eminent domain to get property owners’ sign-off when a waterway on their land is altered. The lawsuit was dropped after Veresen successfully pushed legislation through the Oregon legislature to expedite the permitting process and soften the signature requirement.

Conservation groups fought tooth and nail throughout the state and federal environmental permitting process and local activists have pressured Oregon Governor Kate Brown and Senators Wyden and Merkley to oppose it. But the decision to approve the project ultimately was left to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which, in a rare move, denied the project in 2016.

With the change of federal administration, however, the project is getting another chance.

Veresen CEO Don Althoff was one of the 24 CEOs who met with President Donald Trump in February to discuss American manufacturing. After a March follow-up meeting with White House officials, Althoff told Bloomberg News he was confident the project would be built.

“We talked about what it would take to get the project built and get it going,” Althoff told Bloomberg following the meeting. He said the White House is going to help him “get through the permitting process as quickly and as efficiently … the message to us [from the White House] was, ‘hurry up, get going.’”

Shifting Coos County’s Economy

The project’s 2016 defeat was the result of a multi-pronged opposition. However, throughout that process, a small group of activists called the Coos Commons Protection Council — a local branch of the Oregon Community Rights Network — remained wary of relying on FERC and the regulatory process. Now, with this fossil fuel-friendly White House, their ordinance many be a last line of defense against the LNG terminal.

Beyond merely opposing the natural gas project, the ordinance sets a new vision for economic development in the county.

“We the people of Coos County,” it reads, “have experienced substantial population loss in recent decades due to ill-advised and non-sustainable development policies … [we] have experienced firsthand the harmful effects of unchecked resource extraction.”

Coos County is struggling economically. “When the country gets a cold, [economically speaking],” Radtke, the economist, said, “Coos County gets pneumonia.”

To enforce the “right to a sustainable energy future,” Measure 6-162 states, “the people of Coos County have the right to adopt laws and policies to secure that right,” and “that right shall include the authority to require the development, production, and use of sustainable energy.”

This out-of-the-box ordinance defies numerous deep-seated legal doctrines. “If this measure becomes an ordinance,” a pro-Veresen editorial reads, “our county commissioners can expect to see numerous lawsuits that allege a ‘taking’ of property rights and/or assert violations of the U.S. Constitution’s Commerce Clause (Article I, Section 8, Clause 3).”

Earlier this year, local ordinances in California and Florida have seen similar challenges. There, recently passed local ordinances to regulate rent, raise the minimum wage, and ban hydraulic fracturing (fracking) have already been challenged by private corporate lobbies on similar grounds.

The Coos Commons Protection Council knows it is picking a fight. That’s why the measure states “corporate claims to regulatory takings or future lost profits shall not be considered property interests under this ordinance.”

“We are envisioning a new legal paradigm where communities trump corporations, not the other way around,” said Mary Geddry, a lead petitioner with the Coos Commons Protection Council and Oregon Community Rights Network board member. “We are not trying to hide that.”

Fossil Fuel-Funded Lobby Group at Work in Oregon

In response, Republican state Representative Cliff Bentz, who has received funding from Koch Industries and several oil and gas companies, introduced a bill to prevent municipal control of the fossil fuel industry. As the newspaper Street Roots reported, the bill (HB 2480) itself states that Bentz introduced it “at the request of PacWest,” a large lobbying firm that has worked on behalf of the oil and gas industry in Colorado. (Gas from Colorado would flow through Jordan Cove.)

Pac/West created a front group called Coloradans for Responsible Energy Development to oppose numerous local and state ballot initiatives critical of the fracking industry and to “shift public opinion in favor of energy development.” The group was funded by two energy companies with large gas fields in Colorado — Anadarko Petroleum Corporation and Noble Energy.

Pac/West also managed Protect Colorado, another oil and gas industry funded group, which successfully pushed a state constitutional amendment to make it harder for Coloradans to amend the state constitution through the state ballot initiative process — after anti-fracking and community rights groups advanced the nation’s first fracking-related state ballot initiatives.

Under the bill the lobbying firm is pushing in Oregon, cities and counties would be prohibited from enacting “any charter provision, ordinance, resolution or other provision related to regulating the expansion of infrastructure for the primary purpose of transporting or storing fossil fuels.”

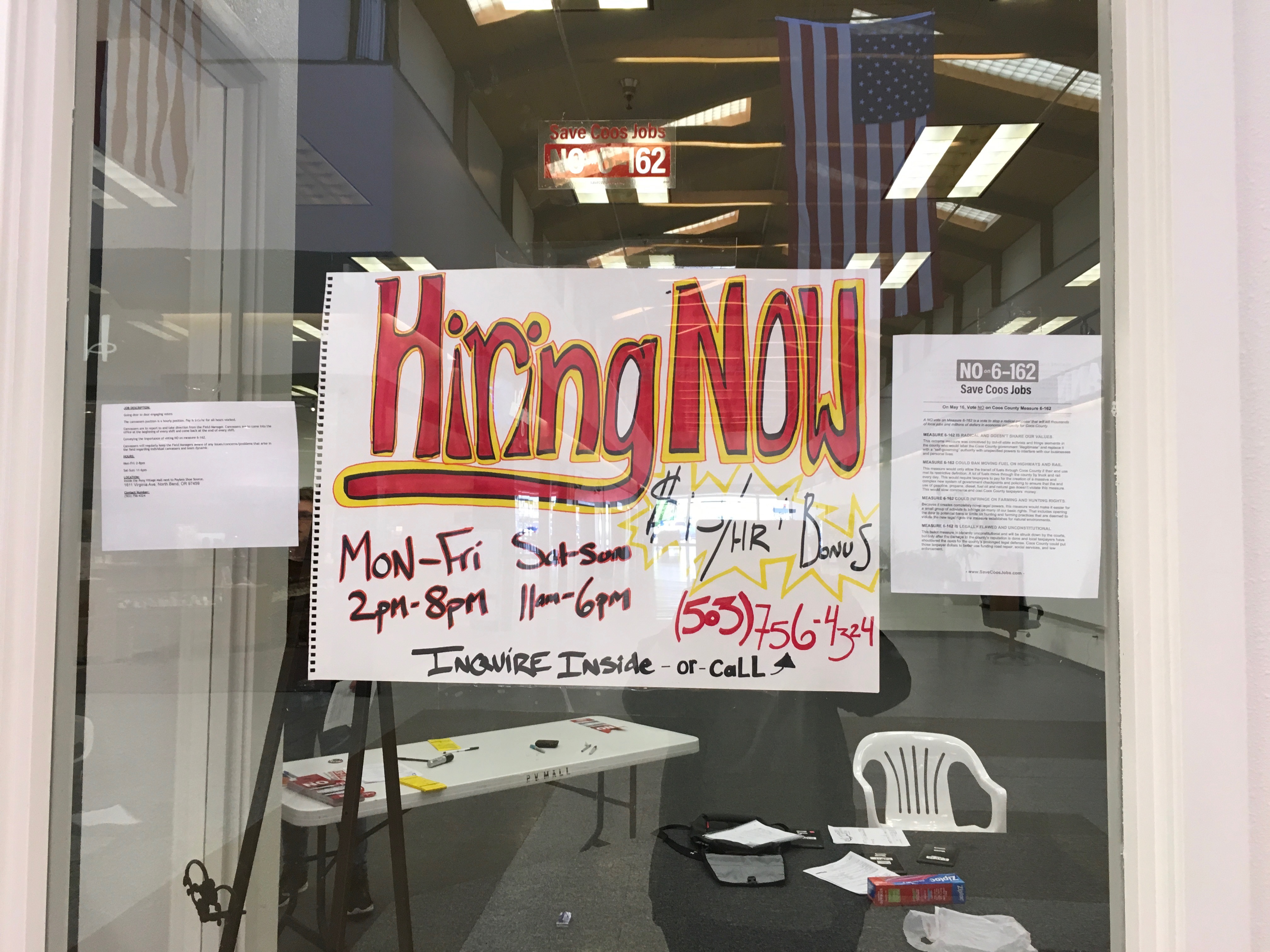

A sign advertising $15 per hour jobs campaigning against Coos County Measure 6-162, which would prevent the opening of the Jordan Cove LNG terminal and associated gas pipeline. Credit: Marry Geddry

With the May 16 vote in Coos quickly approaching, campaigns are in full swing.

The oil and gas industry-backed Save Coos Jobs Committee has hired a “national signature gathering and field company” and is paying campaigners $15 per hour to oppose the measure.

Meanwhile, proponents of Measure 6-162 have received not quite $10,000 in contributions, and have set up an phone banking system for local and other volunteers to help.

“The amount of money we are seeing coming in against our ordinance, proves the point of why we need an ordinance like this,” Geddry told DeSmog.

Read the Dirt helped support the production of this article.

Main image: A rally opposing the Jordan Cove LNG project, June 14, 2016 in Salem and Eugene. Credit: Original photo by Francis Eatherington, CC BY–NC 2.0

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts