“As an American I’m not going to come here and tell the British how to put together a campaign and win, I can only share our experience. And our experience has been that to win you have to develop a strategy at the local level.”

Wenonah Hauter is telling me how anti-fracking campaigners in the UK can keep the shale gas industry out of town. And she should know.

Hauter has been involved in environmental campaigns for decades, starting out at the Union of Concerned Scientists in the early 1990s before moving to groups with a greater focus on citizen action.

The organisation she founded in 2005, Food and Water Watch, was the first US organisation to call for a national ban on fracking. The group was instrumental in getting the state governments of New York and Maryland to ban the practice in 2014 and 2017, respectively.

Fracking is not just about shale gas, “it’s about how we’ve lost our political power”, she tells me between mouthfuls of a Greek salad she’s squeezing in between two of many public meetings she’s been invited to in a short tour across the UK.

We’re in a light, modern restaurant in Preston, chosen largely for its proximity to her next appearance: a late-night coffee shop on the high street.

Earlier in the day she was with the protesters on the frontline at shale gas company Cuadrilla’s controversial site at Little Plumpton, 10 miles to the west.

Anti-Fracking Movement

Companies have been trying to frack in the UK since 2011. Due to a combination of local and national opposition, the industry has yet to get going. But the current government seems determined to make the shale gas industry in the UK a reality.

In 2016, the Communities Secretary Sajid Javid overruled Lancashire County Council’s rejection of Cuadrilla’s plans. With the national government behind the project, Cuadrilla are hoping the Little Plumpton site will be the first of many in the UK.

The company’s activity at the site has been the subject of daily protests. Hauter was there to offer words of encouragement, as well as advice.

“I think that the movement here is at a little earlier stage of development,” she tells me, “so it takes time to build a movement.”

“I think people are still looking for their way for how this is going to be beat, that’s my impression. And figuring out how to maybe have some more coordination.”

“I’m fully confident that the UK will develop a mature strategy that will be a winning strategy to beat it.”

When I visited the site a couple of months previously, I was surprised at the way in which fracking had become secondary to other issues: democracy, localism versus an overbearing national government, and the questionable treatment of peaceful protesters by the police.

Hauter agrees: “The police are acting as a private security force for Cuadrilla.”

She says she joked with the protesters that “the jobs being generated by fracking are police and security jobs.”

“The local media is not doing its job. Because if it even asked simple questions about how is all of this waste from all of these projected drill sites going to be dealt with here, it’s obvious they don’t have any plan.”

The Frackopoly

It’s this message that she hopes to spread around the country as she promotes her new book, Frackopoly – a 368-page analysis of the US shale gas industry, what it means for the environment, and what it represents politically.

“The narrative is we did away with our anti-trust laws, and the oil industry is one example of how public policy has been bought and paid for and shaped our political system. That’s really the ‘opoly’. It’s using fracking as an example of that,” she says.

That’s not an easy subject to communicate, she concedes. “It’s really hard to talk about the ‘opoly’ part of the problem. It doesn’t resonate with people.”

The only way to do that is through concrete examples, she argues. Like the way Enron stitched up the gas markets in the US (which features heavily in the book), or the way the Koch brothers fund climate science denial to further their corporate interests, or even the way in which Cuadrilla or US chemical giant INEOS are approaching the UK market, she tells me.

At one point, she compares the process of companies venturing into a market that isn’t expected to be plentiful or particularly beneficial to the UK‘s economy as a Ponzi scheme.

“I just can’t really imagine that they think that there’s going to be a lot of gas that comes from here. I think a lot of it is they want to see the investments, they want to build the infrastructure. It’s all about this gambling with the financial services.”

But persuading people they are being played by dark money, with companies finding ways to funnel cash into institutions without the public noticing, isn’t enough, she says. You’ve also got to make people care.

That means moving beyond targeting the companies trying to frack, and making broader appeals to the public and officials that sit in positions of power.

“I think it would be good if the movement here got more politicised.”

“When organising — whether it’s electorally or around issues — you have to look at people’s self-interest. And self-interest isn’t necessarily greedy and selfish, it’s why people would want to devote time to this. It’s because these are issues that impact themselves and the people they love.”

Those messages are particularly important when those in power are determinedly on the side of the companies.

A Trump Look-alike

Theresa May’s Conservative party was the only one to support fracking in its manifesto before last week’s general election, so Hauter sees little hope in the new government taking on the industry.

And that allegiance between government and industry can have impacts beyond energy or climate issues.

“I think [Theresa May] is very dangerous, a Trump look-alike.”

“It’s hard to deal with just environmental issues if you’re not dealing with economic issues. The pie is getting small because of austerity measures and the right wing’s attempt to defund government across Europe and the US has to be dealt with.

“Because we just look back in history to see it’s easy to target immigrants, it’s easy to target people who are different than you, and we need to be promoting policies that have fairness for everyone.”

I spoke with Hauter just before the general election in June 2017, with her maintaining hope that “there’s a wake-up here in the UK about the existing government in the same way we need a wake-up in the US”.

I ask, if she were to come back in a year, what would she hope to see?

“I would have hoped that the industry has been halted, stopped in its tracks. That public officials would actually look at some these issues and do their job. That the media would start covering this properly.

“And – because we know these things don’t happen magically – that the anti-fracking movement would be stronger, better coordinated, better resourced. Because this is a long-term battle, not just about fracking. It’s about getting off fossil fuels and onto renewables and energy efficiency.”

In short, it’s about winning. Something Hauter knows about, and something that — after four decades of campaigning — she’s not finished doing yet.

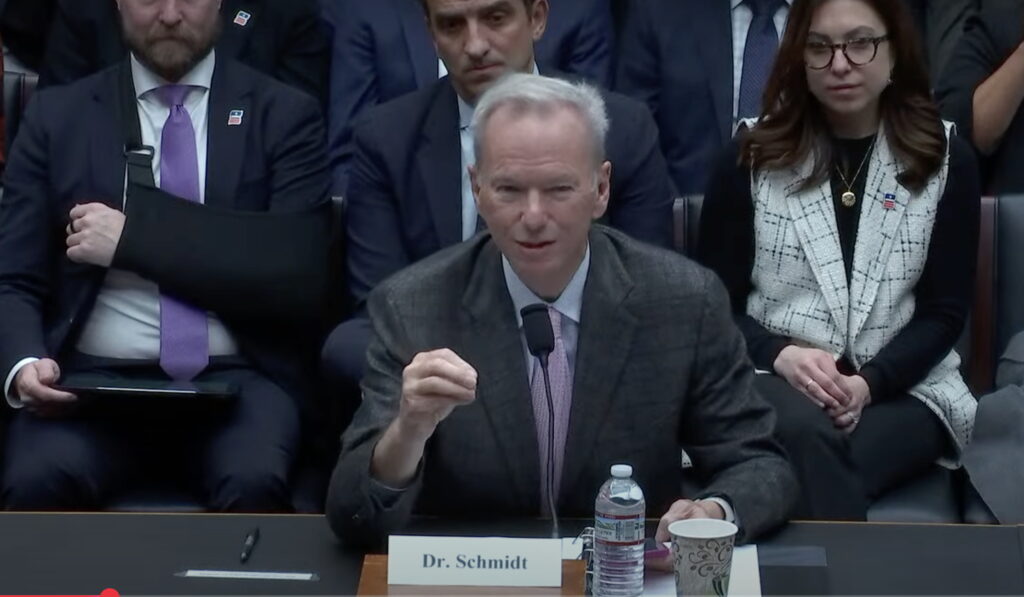

Main image credit: Wenonah Hauter

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts