The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has been called a “deafening” alarm and an “ear-splitting wake-up call” about the need for sweeping climate action. But will one more scientific report move countries to dramatically cut emissions?

Evidence, so far, says no. Countless scientific studies have been published since the 1970s on the dangers of climate change, many offering similar projections. And social science research shows that showing people research doesn’t work. So, if more reports and information don’t spark action, what will?

In a recent study led by the University of Massachusetts Lowell Climate Change Initiative, we identified a promising approach: Playing a game called the World Climate Simulation, originally developed by the nonprofit organization Climate Interactive, in which participants play delegates at international climate change negotiations.

We examined how this experience affected more than 2,000 participants from nine countries, ranging from middle school students to CEOs. Across this diverse population, people who participated in World Climate deepened their understanding of climate change and became emotionally engaged in the issue. They came away believing that it was not too late for meaningful action. These emotional responses were linked to a stronger desire to learn and do more, from reducing their personal carbon footprints to taking political action.

How It Works

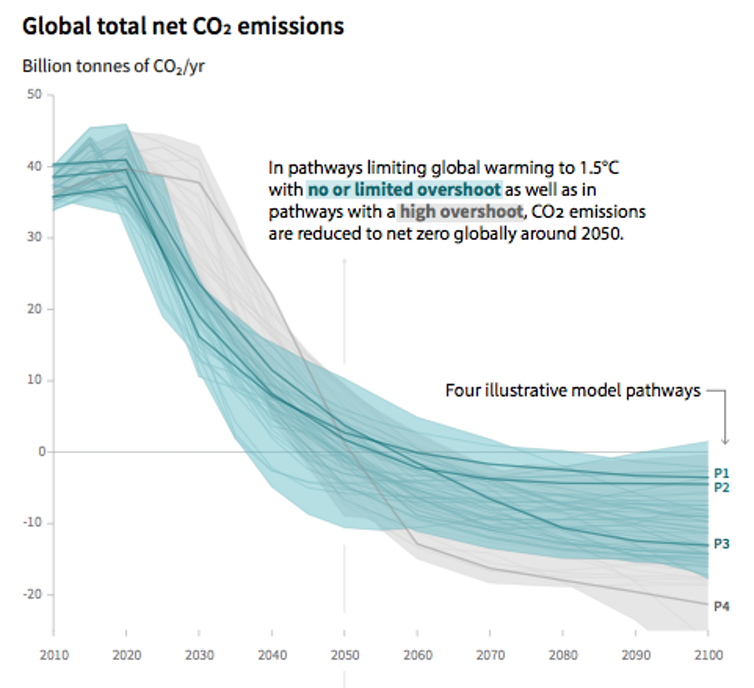

Participants in World Climate take on the roles of delegates from different countries or regions and are charged with reaching an agreement to limit warming to no more than 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit. Each delegation offers policies to manage its own greenhouse gas emissions. They also pledge either to support or request money from the Green Climate Fund, which was created to help developing countries cut their emissions and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Each group’s decisions are entered into C-ROADS, a climate policy model that has been used to support actual negotiations, immediately showing them the expected climate impacts of their choices. First round results usually fall short as participants resist making deep cuts to their own region’s emissions, demand more money from the Green Climate Fund, or assume the pledges they and others have made are enough to meet the global goal. When those pledges are not enough, the simulation shows everyone the harm that could result.

Participants then negotiate again, using C-ROADS to explore the consequences of more ambitious emission cuts. As in the real world, people learn through trial and error until they succeed. But unlike the real world, there is no cost or risk of failure.

For many players, the impact is deep and personal: “I feel like I was a part of something way bigger than myself. I am going to look for ways on campus to get involved,” one undergraduate participant said afterward.

“Since the simulation, I … have been continually thinking about the effects of our consumption and how it affects others,” a high school educator reflected.

Play Together, Not Just With the ‘Usual Suspects’

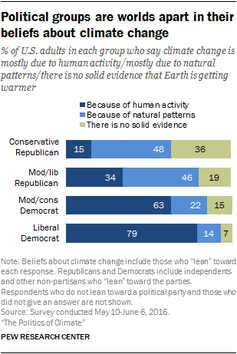

Climate change has become highly politicized in the United States, with political orientation often determining people’s views, rather than science or data. For example, conservatives who oppose international agreements or government action to address the problem often react by denying that climate change is real, or is caused primarily by human actions, or poses a grave threat to our prosperity, security and health.

Overcoming this barrier has proven to be extremely difficult, yet is essential for effective action. We were therefore quite surprised to find that World Climate is effective with Americans who are free-market proponents – a political view linked to denial of human-caused climate change. World Climate also has a bigger impact on people who were less inclined to take action or knew less about climate change before the simulation than those who were already engaged.

While most Americans say that climate change is important to them, they don’t talk about it in their daily lives. World Climate is a richly social experience that breaks down this “spiral of silence.” As participants negotiate, they talk about the issues face to face. They discover shared concerns, which creates an opportunity to move on to the important next step: Doing something about them.

Getting to Scale

Mitigating the threat of climate change requires science-based, grassroots action at scale. And as the IPCC report makes clear, there’s no time to waste. However, telling people about the threat doesn’t work. They have to learn for themselves; our research shows that World Climate can help.

Everything people need to run World Climate, including the C-ROADS model, is freely available online. The program is aligned with U.S. national education standards and has also been designated as an official resource for schools in France, Germany and South Korea. It is adaptable and relevant to academic disciplines ranging from physics to ethics.

Since mid-2015 World Climate has been played by more than 46,000 people in 85 countries, including students, community groups, executives, policymakers and military leaders. More than 80 percent said it increased their motivation to combat climate change, regardless of their political orientation or prior engagement with the issue. Our research shows that World Climate acts as a climate change communication tool that enables people to learn and feel for themselves – experiences that together have the potential to motivate action informed by science.

For most of history, experience has been humans’ best teacher, enabling us to understand the world around us while stimulating emotions such as fear, anger, worry and hope that drive us to act. But waiting for experience to show how disastrous the impacts of climate change could be is not a realistic option. Just as pilots train in flight simulators so they can save passengers when real emergencies strike, people can now learn about climate change through simulated experience and become motivated to address it, instead of suffering the real-world consequences of inaction.

Co-authors of the study described in this article included J.D. Sterman, MIT Sloan School; T. Franck, E. Johnston and A.P. Jones, Climate Interactive; E. Fracassi, Instituto Tecnologico de Buenos Aires; F. Kapmeier, Reutlingen University; K. Rath, SageFox Consulting Group; and V. Kurker, UMass Lowell Climate Change Initiative.

Juliette N. Rooney-Varga is Associate Professor of Environmental Science at the University of Massachusetts Lowell.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts