Just before the November 2024 election, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released its flagship annual report on global energy markets – and the agency’s forecast suggested a new era was dawning.

Over 150 years of growth in demand for fossil fuels has nearly reached its end, the IEA’s forecasts showed for a second year in a row. Fossil fuel demand will peak by the end of this decade, the organization affirmed, concluding that clean energy like wind, solar, and storage look increasingly capable of driving fossil fuels out of global energy markets – and soon.

That would be relatively positive news for the climate – but for fossil fuel producers, that message posed a major threat, given that even the prospect of stagnating demand on the horizon could chill investment.

But in recent months, artificial intelligence (AI) proponents have begun talking up the idea that AI and data centers can drive a surge in fossil fuel demand, prolonging the fossil fuel era – big tech’s earlier climate pledges notwithstanding.

After successfully convincing Saudi Arabia, the world’s second-largest oil producer, to relax regulations and support AI development, tech industry advocates are now bringing that same promise of endless fossil fuel demand to the world’s largest oil producing country, the U.S.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

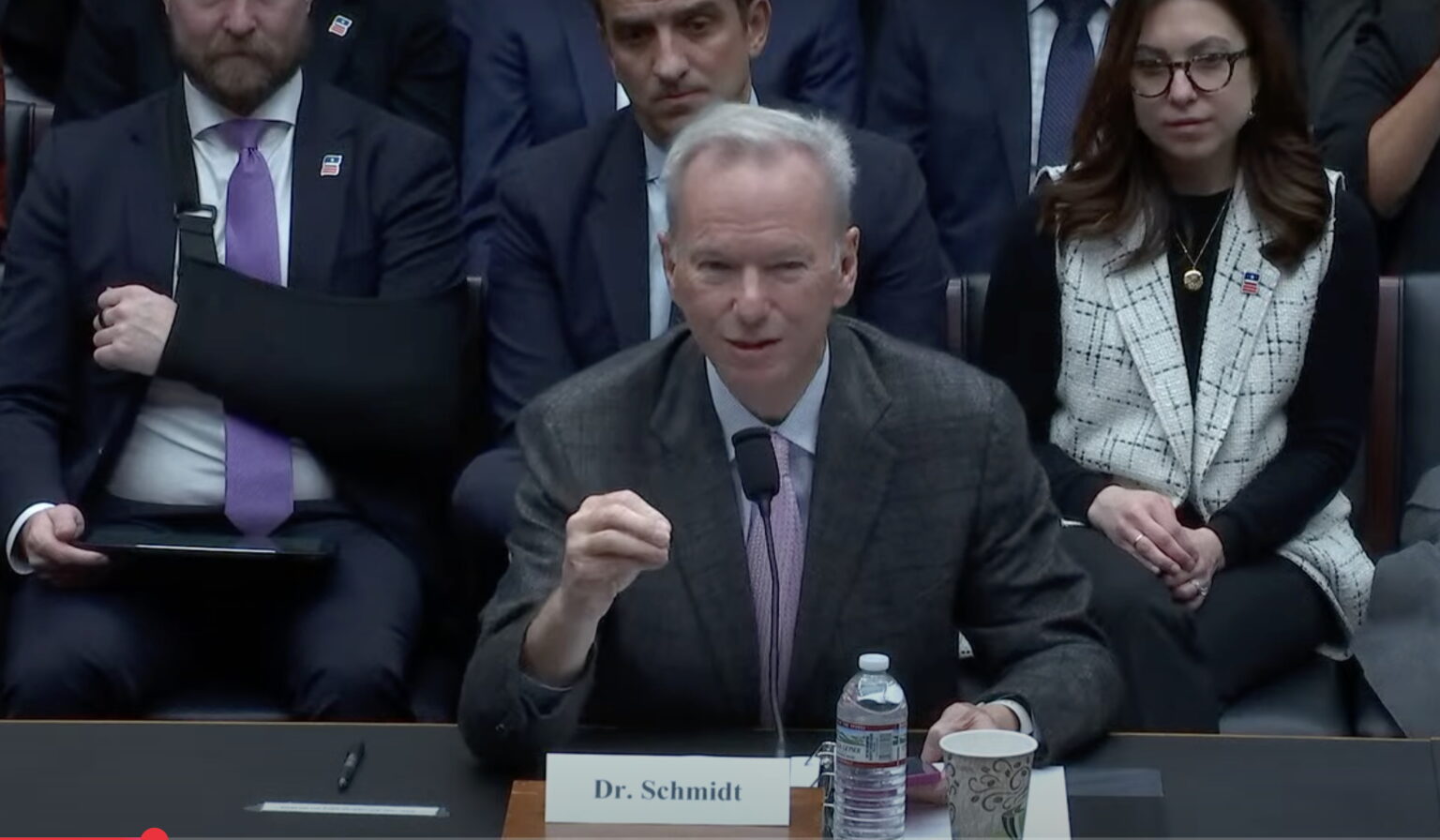

“We need energy in all forms,” Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google, now chair of the pro-AI think tank, Special Competitive Studies Project, told a Congressional hearing on April 9. “Renewable, nonrenewable, whatever.”

Schmidt, whose organization published a roadmap on AI for the Trump administration, was testifying before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce.

Schmidt has a history of shaping U.S. laws on AI, previously serving as chair of the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence, which under his watch wrote legislative proposals that later became law. The committee’s hearing on AI was inspired, according to its chair, Rep. Brett Guthrie (R-KY), by Schmidt’s recent work.

“If you think about it, it’s going to take enormous energy to beat China to AI,” Guthrie said as the hearing kicked off, emphasizing his desire to make AI rules that would endure beyond the next two to four years. “Dr. Schmidt, you said all energy resources are needed,” he said, “and then AI will develop solutions to deal with climate change.”

Climate experts have warned that it’s not that simple. AI is at best a double-edged sword for the climate — in part because the technology requires so much energy.

Just the day before the House Committee on Energy and Commerce’s hearing, Trump signed a raft of executive orders promoting coal, the latest in a volley of executive orders and administrative moves to deregulate and subsidize fossil fuels, citing AI demand expectations.

Schmidt has carried the same promise to top Saudis – drawing a similar positive response.

Saudi Arabia’s climate plan – which earns a failing grade from climate watchdogs – involves the use of carbon offsets and net-zero math, including the country’s Voluntary Carbon Market, backed by Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund (PIF), the nation’s sovereign wealth fund.

Before Trump took office, the U.S. earned slightly better marks than the Saudis – meaning that the more the U.S. follows the path forged by Saudi Arabia, under the influence of AI advocates, the worse the climate impacts can be expected to be for the entire world.

‘We’ll Take Everything You’ve Got.’

Earlier this year, President Trump appeared in person to give a presidential address launching the Future Investment Initiative (FII) Priority conference in Miami, which was attended by roughly 10,000 representatives from companies and organizations around the world.

On the conference’s final day, Schmidt held a “special conversation” with Saudi Arabia’s Yasir Al-Rumayyan, chairman of Saudi Aramco’s board of directors, the governor of PIF, and chair of the FII.

“We are very well positioned to be a major modern champion when it comes to AI, for the following reasons,” Al-Rumayyan told Schmidt during the panel.

“One, we have the political will. With that comes all easing the regulations,” Al-Ramayyan said.

Two, he said Saudi Arabia has the funds to be invested; and three the nation has people, “Saudis and otherwise.”

“Four, which is the most important — and I remember when we started talking about AI, everyone was looking at the AI stack and they were forgetting the most important element — which is energy,” the businessman continued. “And energy we have so much of.”

“We can use it all,” Schmidt responded. “AI people, we’ll take everything you’ve got.”

The friendliness between AI boosters like Schmidt and Saudi officials comes despite a host of concerns outside experts raised during the conference over the Saudi PIF’s record on human rights.

“Our warning is: This fund is directly associated with human rights abuses and is facilitating human rights abuses,” Nicole Widdersheim, deputy Washington director of Human Rights Watch, told reporters outside the conference, citing the 2018 murder and dismemberment of journalist Jamal Khashoggi at the Saudi consulate in Istanbul. The Saudi government has denied U.S. allegations that crown prince Mohammad bin Salman approved Khashoggi’s killing.

Widdersheim also pointed to human rights issues faced by foreign workers in Saudi Arabia. “The fund has led the massive investment of these huge mega economic projects domestically inside Saudi Arabia,” she noted, like Saudi Arabia’s Neom project. “These investments have attracted and recruited immigrant workers from all over the world who paid exorbitant fees to come there and work, and who work under extreme heat exhaustion and unsafe conditions,” she said. “Many have died. They are not earning their salaries when they’re working there and then when they die, their families are not even compensated.”

Voluntary Carbon Market: Same Oil Tricks

Many big tech companies have historically balked at building out new fossil fuel infrastructure, given the growing climate impacts.

At the conference, Al-Rumayyan himself hastened to point out that the energy Saudi Arabia produces isn’t all oil and gas.

“And the good thing, it’s not fossil fuel-based energy only,” he told Schmidt. “It’s renewable. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is really big. And it works very well with solar energy. Wind is also there. We have some spots — one of the best spots for wind turbines.”

PIF also owns 80 percent of the Saudi company, Voluntary Carbon Market (VCM).

“One of the things we think of Saudi Arabia as is a petrol state,” Riham ElGizy, the CEO of VCM, said during a side panel at the FII Priority conference. “But we forget Saudi Arabia is one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change.”

“The impact of desertification has extended heat waves,” she said. “That’s why you find a lot of companies aware of climate change. They are taking action and they want to participate.”

Carbon markets like VCM operate by offering buyers the chance to offset their emissions by buying “credits” for greenhouse gas reductions elsewhere.

VCM is a path for developing nations, regardless of credit score or high interest rates, to add liquidity to their financial portfolios as 60 percent of climate finance is borrowed. Through gaining points in the market from meeting climate pledges, global shifts in energy use and types of energy are expected to follow. However, with kickbacks from pledges followed through, the use of fossil fuels can sustain without negatively disturbing a country’s carbon score.

But experts say the industry’s been plagued by questionable math and a lack of transparency.

“There has been a lot of integrity issues coming out,” ElGizy acknowledged at the conference. “Navigating around that, we needed to double down in scrutiny. We have no room for mistakes in this.”

In November, VCM auctioned off carbon credits it said were created from a range of projects, including efforts to capture methane from landfills “from across the Global South,” an Ethiopian forest restoration project, and an unnamed U.S. company that VCM says is “aiming to capture, inject and embed carbon dioxide into fresh concrete.”

Saudi plastics makers, petroleum refiners, energy traders and others were among the buyers, according to VCM.

‘Insufficient’ Climate Policies

Its first three auctions included enough carbon credits to cover the emissions produced by six million cars in one year, the company says – which, using U.S. federal estimates for vehicle emissions, would imply VCM has auctioned off credits offsetting nearly 10 million tons of carbon dioxide per year since it launched in 2022.

That 10 million tons, however, represents a vanishingly small fraction of the carbon produced each year by Saudi oil. Roughly 3.3 billion barrels of crude flowed out of Saudi Arabia in 2024 – enough oil to spew about 1.4 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the Earth’s atmosphere last year, based on federal greenhouse gas equivalencies.

Climate Action Tracker, a scientific project that compares countries’ climate policies against Paris Agreement standards, rates Saudi Arabia’s climate policies as “critically insufficient,” which means the country’s climate policies “reflect minimal to no action and are not at all consistent with the 1.5°C temperature limit.”

“Saudi Arabia has not implemented any policies that would substantially bring down its greenhouse gas emissions and reduce its reliance on fossil fuels,” the group says. “Previously announced plans to cut emissions through expanding renewable energy are failing to materialise. Despite its ‘Vision 2030’ diversification plan, initiated nearly a decade ago, the Saudi economy remains highly dependent on the production, use and export of hydrocarbons.”

And in fact, Saudi Arabia’s national oil company, Saudi Aramco, said at the PIF conference that it has “stayed the course” throughout the energy transition — the implication being the company has little intention to shift away from fossil fuels.

Fahad Al-Dhubaib, an Aramco senior vice president, emphasized the national oil company’s carbon capture and hydrogen plans, plus the company’s “carbon intensity” (an often-critiqued measure of how much pollution is generated from its own operations, shifting the focus away from the climate-altering pollution that comes from burning that oil).

But the company’s first objective, Al-Dhubaib said, is “How do we meet the increasing energy demand?”

Artificial Demand

The AI industry, of course, has been on a meteoric rise since ChatGPT was first released to the public in 2022.

“In the past few years, AI has gone from an academic pursuit to an industry with trillions of dollars of market capitalisation and venture capital at stake,” the IEA wrote in a report released April 10.

But as a share of global energy demand, AI remains still just a tiny sliver, the IEA noted, reflecting about 1.5 percent of world electrical consumption in 2024.

AI is expected to continue to expand faster than other sectors – but the IEA predicts the lion’s share of that demand can be met with renewable energy, which the agency noted enjoys a number of advantages over fossil fuels, including faster deployment, lower costs, and smaller climate impacts.

By 2035, the agency projects renewables’ electrical generation will grow by over 450 terawatt hours to meet data center demand – compared to 175 terawatt hours for natural gas.

There could be climate advantages from an AI boom, the IEA noted.

“Energy innovation challenges are characterised by the kinds of problems AI is good at solving,” it wrote. “For example, only 0.01% of next-generation solar PV materials have been experimentally produced, leaving a huge set of possible materials still to be explored. AI could allow scientists to dramatically accelerate the process of finding and testing promising materials, battery chemistries and carbon capture molecules.”

That said, it’s not clear that the biggest barriers for a renewable energy buildout at this point are technological, given the advantages the IEA noted that wind, solar, and storage already enjoy over natural gas.

In fact, as the nation’s power grid expands, public policy could play an even bigger role, potentially overshadowing advantages that renewables might have over fossil fuels.

“House Republicans are poised to vote on a budget resolution that would set the stage to repeal the energy tax credits incentivizing well over 90 percent of the electricity generation poised to come onto the grid,” Frank Pallone, ranking member of the Energy and Commerce committee noted at the committee’s April 9 Congressional hearing, referring to tax credits for renewable energy.

It’s also far from clear that the tech industry will prove to be as hungry for fossil fuel power as some predict. First, advances in AI technology could drive energy consumption down. Concerns are emerging that the technology may not fully live up to the hype, at least from investors’ standpoints, with Alibaba Group chairman Joe Tsai telling a Hong Kong investment summit in March that data construction may have already reached “the beginning of some kind of bubble.” Plus, the Trump tariffs have injected extraordinary levels of uncertainty into global markets, leaving some experts wondering if the upheaval could derail an AI boom.

When it comes to domestic AI policy, U.S. Republicans have signaled their intent to look beyond European institutions as they think about energy policy and AI demand. “I believe you said in your presentation, Europe has chosen not to grow,” Rep. Guthrie said to Schmidt at the April 9 hearing, “so we can’t look there as an example.”

And indeed, it seems, the path on AI and fossil fuels that the Trump administration is taking the U.S. down just might look strikingly similar to the one forged by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts