UPDATE (April 15, 2025 1:11PM PDT): Since this story was published, Balico has requested the withdrawal of its application to rezone about 760 acres of land to allow it to build a natural gas power plant and data centers. The company’s request to withdraw its rezoning request will be on the agenda for Tuesday night’s public meeting, a Pittsylvania County spokesperson said.

“In all my days here, this is the biggest black eye that Pittsylvania County has experienced,” says Amanda Sink Wydner, leader of the local opposition to plans for a massive new power plant and data center complex in Chatham, a small town in southern Virginia.

On April 15, the county government will vote on whether to rezone hundreds acres of farmland to heavy industrial use, which would allow Balico LLC, a natural gas power developer, to proceed with the project. As planned, it would have the biggest power demand of any data center complex in the world, according to rankings from Data Center Magazine.

The plans have left county residents deeply divided, says Wydner, between those who see the project as a threat to their rural way of life, and those who envision it as an economic opportunity that will increase tax revenues.

The Town of Chatham, the Chatham Garden Club, the NAACP Pittsylvania County Branch, and local community groups Concerned Citizens Chalk Level, Friends of Whittles, and the Coalition for the Protection of Pittsylvania County have voiced their opposition.

Some opponents say that the conflict is not about data centers themselves, but where to site them: on farmland or in established industrial parks.

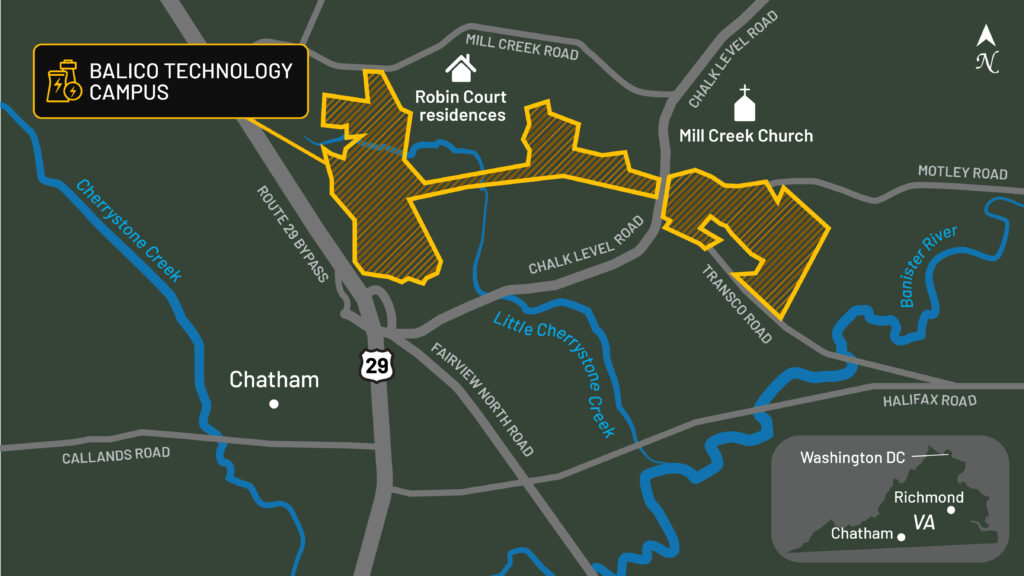

Most locals first heard about the plan in October, when Balico made its initial request to rezone more than 2,200 acres (890 hectares) of agricultural land for an 84-building data center campus. By that time, Balico had signed contracts with various landowners willing to sell their land that gave the company special power of attorney to request the rezoning on their behalf, according to documents shared with DeSmog by residents, who obtained them via a freedom of information (FOI) request.

The documents showed that Balico has been meeting confidentially about the project with county officials, local landowners, Virginia state representatives, and other major stakeholders since at least as far back as December 2023.

Opponents of the project have criticized a nondisclosure agreement between Pittsylvania County and Balico, signed on December 13, 2023, alleging a lack of transparency on the part of local officials.

Pittsylvania County Director for Economic Development Matthew Rowe says that nondisclosure agreements are standard practice when companies want to discuss doing business in the county, because they give county officials a seat at the table “so they can directly learn every intricate detail possible as they weigh a given proposal and determine if it meets the needs and expectations for county residents at-large.”

“The process is working as it’s designed,” says Rowe. “The county wants to explore any and all opportunities for its residents, while also respecting the right of due process for any potential private individual or entity pursuing a rezoning and/or special use permit. Pittsylvania County’s elected officials review every single project on its own merit.”

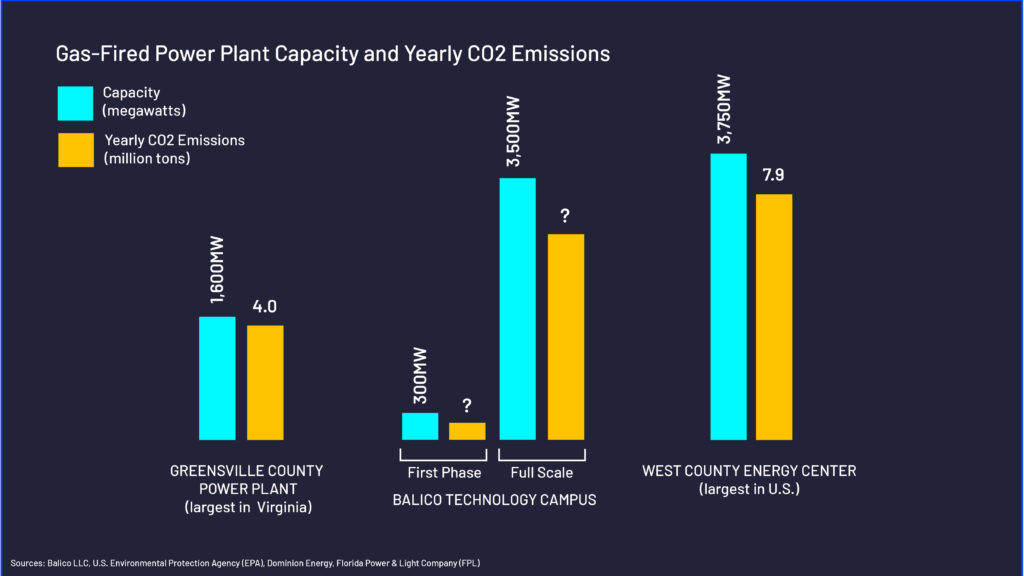

In November, Balico downsized its rezoning request to about 760 acres (308 hectares) — but left the size of the original plan’s 3,500-megawatt gas-fired power plant unchanged. If built, it will be the second-largest gas fired power plant in the United States and the largest in Virginia, rivaling the entire power demand of northern Virginia’s “Data Center Alley,” where over 200 data centers carry 70 percent of worldwide internet traffic, the Oxford American has reported.

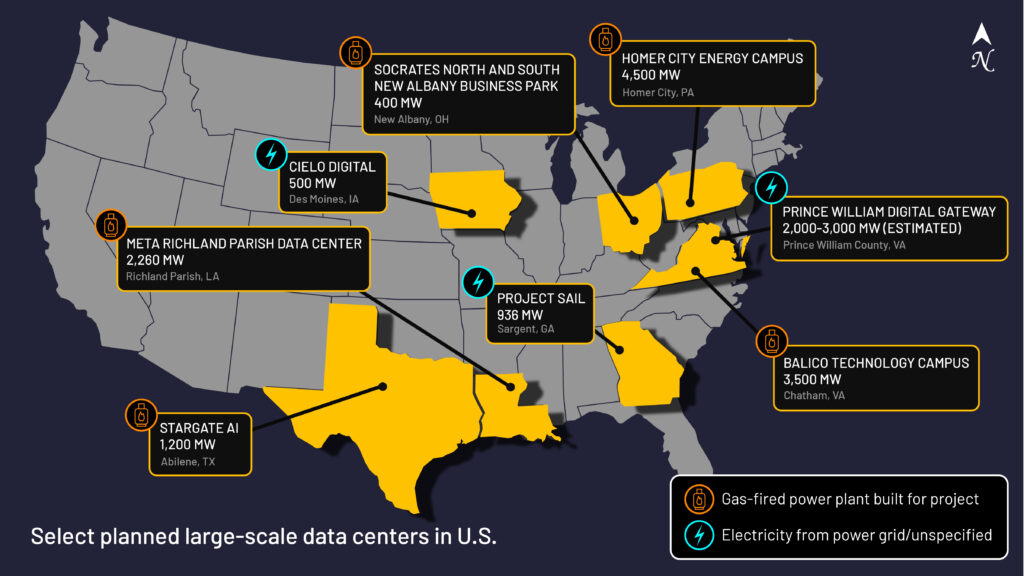

Balico’s proposed data center is part of a data center boom in suburban and rural communities across the United States, spurred on by massive investments in artificial intelligence (AI), and often fueled by a natural gas industry hungry for new customers. Developers are in search of land, water, energy, and regulatory support to build a new generation of massive gigawatt-sized data centers in states including Maryland, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Louisiana, and Texas.

With the power demand from the data center build-out rapidly increasing, new natural gas, nuclear, and renewable energy projects are being planned nationwide to fuel the surge. A U.S. Department of Energy report published in December estimates that between 2023 to 2028, the growth of artificial intelligence could triple data center power demand from 4 to 12 percent of total national power demand.

Dominion Energy, Virginia’s largest electricity producer, projected in a 2024 report that the state’s overall power demand will double by 2039. Ed Baine, a senior Dominion Energy executive, termed this “the largest growth in power demand since the years following World War II.” Data center growth is largely driving the surge. The report lays out an “all the above” approach for sourcing that energy.

President Donald Trump is making AI development a top priority. “We’re letting people build their own power plants. A lot of them are being built with the AI and beyond the AI,” Trump said at an April 10 cabinet meeting. “They couldn’t believe it when I told them that we’re going to get you your approvals very fast.”

‘A Troubling Message’

The scale of Balico’s plans has left some Chatham residents stunned. Wydner, the local opposition leader, recalls that during an informal meeting in October with the county community development commissioner, two of her elderly neighbors burst into tears when they saw maps of Balico’s extensive plans. “There was a feeling of hopelessness, frustration and misunderstanding in the room,” Wydner said.

Among the concerns of hundreds of local residents opposed to the project: bulldozing over farmland, unsightly buildings, air and water pollution, heavy construction traffic, constant noise from data center operations, and the guzzling of millions of gallons of water a day, needed to cool both the power plant and data center servers.

In a video posted to Facebook, a 16-year-old county resident told the board of supervisors during a public meeting that Balico’s project “sends a troubling message to the next generation.”

Noting risks to the local community, including depreciating land value, loss of farmland, impacts on farm animals and wildlife, and increased emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other air pollutants, the teenager said: “It will be a struggle for younger people such as myself to call this county my home in the future if we cannot take control of this problem before it spreads like wildfire.”

Balico did not respond to multiple requests for comment concerning the environmental impacts of its plans. The company wrote in a March 28 Facebook post that the project has been “designed to integrate seamlessly with the existing community” and “will preserve the area’s peaceful atmosphere.”

Local supporters of Balico’s plans can be found in the town of Hurt, 19 miles to the north of Chatham. Hurt’s mayor, Gary Hodnett, has been a vocal supporter of the project, noting the improvements that Balico says it will make to the town’s water infrastructure, including a new water treatment plant, as well as the tens of millions of dollars of projected tax revenue.

At a March public meeting, Hodnett told the Pittsylvania County board of supervisors that “you have an opportunity to bring development to our county, something you should savor,” adding that, “We are geographically the largest county in the state, and yet we remain among the poorest.”

On December 3, the Town of Hurt announced its support for the Balico project and released a letter of intent to supply two million gallons of water a day to the data center campus.

Big Bets

While many data center projects are led by big names in tech such as Amazon and Microsoft, smaller developers with no known experience in the data center industry, like Balico, are also pitching multi-billion dollar investments.

Balico LLC was incorporated in 2005 and registered to the address of a residential townhouse in Herndon, a Washington suburb, according to Virginia state business records. According to Fairfax County property records, the townhouse was owned until 2023 by Balico CEO Irfan Ali. Balico’s public address leads to an office building near Dulles International Airport.

Balico has its roots in the natural gas industry. Ali previously worked on the development of a large-scale coal power project in Pakistan (which appears not to have been constructed) as well as other natural gas power projects in the U.S. Timothy Seibert, the president of a large Ohio natural gas pipeline contractor, has made repeated appearances alongside Ali on calls with county officials in the past year. Balico did not reply to a question about his involvement with the company.

During a January public meeting in Pittsylvania County, Balico attorney Steven Gould stated that the company has seven employees. “As Balico undertakes larger development projects, that number will grow,” said Gould, “The company is set up to flex as project needs dictate.”

Ali is also the founder and CEO of a company called CarbonKerma, which sells CO2 pollution offsets, a business he describes on his LinkedIn profile as “promoting climate pragmatism.” Milton Catelin, who was the secretary general of the International Gas Union, an industry trade group, from 2022-2024, is listed on CarbonKerma’s website as a member of its board of advisors.

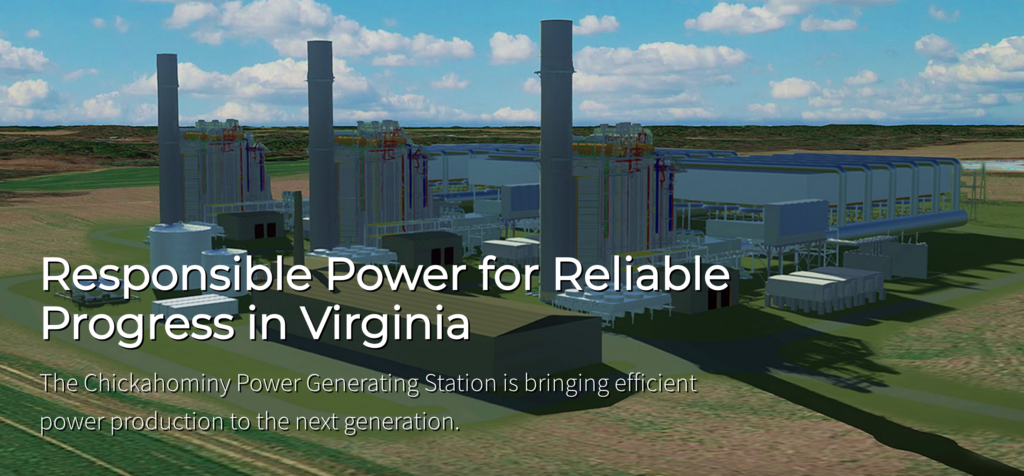

A former executive at North Carolina-based power company Congentrix, Richard Gray, was involved in Balico’s ultimately unsuccessful effort to develop a 1,600-megawatt gas-fired power plant in Charles City County called Chickahominy Power, according to call transcripts obtained in the FOI request. It is unclear whether he is involved with the project in Pittsylvania County.

The project also included construction of a natural gas pipeline in five Virginia counties.

At the time, Balico did not disclose the source of the money behind the Chickahominy Power project, which had the support of the Charles City County board of supervisors. “I am the investor, and the investors behind this are multinational institutions that cannot be named,” Ali told the Richmond Times Dispatch in 2021.

State lobbying records show that in 2019-2020, Balico spent $12,500 on lobbyists to weigh in on Virginia laws regulating pipelines, electric utilities, and CO2 emissions.

In 2020, a Charles City County citizen group called C5 mustered opposition against the Chickahominy Power project, in which “1,199 individuals commented or participated in the public hearing on the ‘Special Exception’ for water to supply the Chickahominy gas plant,” according to the group’s website.

In Louisa County, which was in the path of the Chickahominy Pipeline, the board of supervisors challenged Balico’s proposal during a contentious October 2021 public meeting, according to video of the event on the county website, asking the company’s representative why public officials had not been informed before the company started contacting local residents to conduct surveying work on their land.

“I’ve been in business for 42 years, sitting on this board for four. That’s the worst presentation I’ve ever seen in my life,” one of the supervisors told Balico’s representative.

Balico dropped the Chickahominy Power project in 2022, after the Virginia State Corporation Commission, which regulates utilities, denied the company’s request for an exemption from the agency’s rules regulating the construction of pipelines.

Balico’s search for an alternative location to develop a major gas power project led it to Pittsylvania County, where two major natural gas pipelines intersect. Letters, emails, slide presentations, site plans, and call transcripts dating between December 2023 and October 2024, obtained under the FOI request, document Balico’s efforts to get key county decision-makers to support the project.

In an early e-mail exchange, dated December 7, 2023, Ali asked Rowe, the Pittsylvania County director for economic development, “to keep our enquiries [sic] as quiet a possible” to develop the power and data center project.

“My experience has been that if word gets out to various political factions in Richmond” — Virginia’s state capital — “they start organizing right away and come up with delaying tactics,” Ali added.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

Ali suggested in a June 3 conference call with Pittsylvania County officials that a changing political climate had improved Balico’s chances of success in building a large gas-fired power plant.

“The difference though… this time from last time, is that we have the entire government, state government, ready to support us,” Ali said during the call, adding that “the governor’s office is on board,” according to a transcript.

Virginia’s governor, Glenn Youngkin (R), supports expanding the state’s data center industry, saying in a January address that it has brought 74,000 jobs and $9.1 billion to the state.

On May 22, in a meeting titled “Project Ballyhoo Discussion,” Balico met with Darrell Dalton, who at the time chaired the county board of supervisors, as well as then-vice chair Robert Tucker, who now leads the board along with other county officials. In the following months, Balico would meet with county officials regarding rezoning requirements, along with state environmental regulators, according to the documents, which show Balico’s concerns over potential opposition and the company’s efforts to engage with state lawmakers.

Notes from an August 8 meeting between Balico and the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, a state agency known by its acronym VADEQ, say that: “Concerns were raised about opposition from anti-fossil fuel groups, leading to discussions on project phasing versus a single large permit project.” A transcript of the meeting was not provided.

Another document indicates a meeting titled “Coffee with Delegates Marshall and Phillips, Balico LLC” on August 22, 2024 at the Institute for Advanced Learning and Research in Danville, and lists Virginia state delegates Danny Marshall (R) and Eric Phillips (R) as attendees. This meeting was followed by a request by Balico to the state delegates on August 30 for a “meeting to discuss necessary changes needed to the utilities act.” Marshall and Phillips’ offices did not respond to requests for comment.

That meeting, originally set for September 13, appears to have been cancelled, but further documents show that Balico continued to communicate with the state delegates, informing them in October of a major gas deal signed for the project and the importance of legislative support. The exchange also included Chief Stephen Adkins of the Chickahominy Indian Tribe, whom Balico referred to as a “partner” in the project in a May 16 email to county officials. Adkins did not respond to a request for comment.

In January, Philips voted against a bipartisan bill requiring data center developers to submit an assessment of noise, land, and water impacts of proposed facilities before obtaining rezoning approval. Marshall was absent for the vote.

In March of this year, the state’s General Assembly passed the bill, which is the only survivor out of more than two dozen bills introduced this year concerning data center planning. Gov. Youngkin has since proposed an amendment that would weaken the legislation, according to reporting by Virginia Public Radio, likely pushing any moves to implement the bill into 2026.

Concerns raised by Virginia residents about the growing presence of data centers range from local environmental impacts to climate-heating CO2 emissions, as well as the strain that data center power demand is putting on Virginia’s grid, often leading to increased electrical costs.

Data center and power companies such as Balico are increasingly looking to bypass the power grid by bringing natural gas directly from the gas wells to the power plants. The fracked gas for Balico’s project in Pittsylvania County would come from the shale formations of the Appalachia region of the eastern U.S., taking advantage of a well-established fracking industry and gas pipeline infrastructure.

On July 8, Pittsburgh-based EQT, a major gas producer, signed a letter of intent with Balico to supply gas to the planned Pittsylvania facility, according to a document obtained through the public records request. EQT owns the recently completed Mountain Valley Pipeline, a 303-mile-long (488 km) pipeline that begins amid the fracking wells of West Virginia and terminates in Pittsylvania County.

In a 2024 interview with Hart Energy, an energy industry trade publication, EQT CEO Toby Rice called the artificial intelligence boom, a significant driver of the surge in data center projects, a “really amazing technological revolution” that will be “powered by Appalachian gas.”

Fueled by EQT’s shale gas, the full-scale 3,500-megawatt power plant described in Balico’s revised rezoning request could become one of the largest sources of CO2 emissions in the U.S.

A similar-sized gas-fired power plant in Florida — the 3,750-megawatt West County Energy Center, built in 2009 and currently the nation’s largest — produced 7.9 million tons (7.1 million metric tonnes) of CO2 in 2023, the last year on record from the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) emissions database. That’s the equivalent yearly CO2 emissions of about 1.5 million cars, according to EPA figures.

.

For the first phase of its operations, Balico plans to power the growing data center site with 300 megawatts generated by what are known as “aeroderivative gas turbines” — which are designed similarly to jet engines — until the larger 3,500 megawatt facility is built.

In a March 24 Facebook post, Balico said that new natural gas power plants pollute less than “filling your car up at a gas station.”

Opponents on Edge

Since November, local residents have packed into monthly board of supervisors meetings, united under the slogan “No data centers, no power plants in rural neighborhoods.”

Now many are on edge ahead of Tuesday’s rezoning hearing, uncertain of what the outcome will be. In anticipation of an overflow crowd, the meeting has been moved from its usual location to Chatham High School.

In January, the Pittsylvania County Planning Commission unanimously recommended that the board of supervisors reject Balico’s rezoning request, noting a “lack of transparency by the applicant, the timing of the proffers being submitted, concerns about the availability of water, the size of the power plant and that the project does not align with the County’s comprehensive plan.”

The county board of supervisors has granted Balico two extensions since Feburary to rework its proposal, further worrying the projects’ opponents.

In a statement to the Chatham Star Tribune published on April 4, Pittsylvania County spokesperson Diana McFarland said that the county has “historically allowed rezoning applicants the freedom to postpone a public hearing or vote on their application” and that “the County is providing Balico, LLC with the same courtesy it has granted rezoning applicants in the past.”

If it goes forward, this will not be Pittsylvania County’s first big data center project to win rezoning approval. In July, Anchorstone Advisors SOVA LLC obtained approval from the county to rezone 950 acres (380 hectares) near the town of Danville, 16 miles south of Chatham, to build a 200-megawatt data center campus.

While Anchorstone’s proposal passed with far less public opposition, the wide-ranging community debate about the Balico project has raised questions about the future of Pittsylvania County’s rural character.

Large-scale solar power installations already cover thousands of acres of county farmland, feeding power to other parts of Virginia — all the way to Arlington, a northern Virginia suburb of Washington that is home to Amazon’s corporate headquarters.

Some rural residents see the intensifying competition for land as a wake-up call to preserve their way of life.

“All I’ve heard in the past months is money, money, money,” said Darrell Campbell, pastor of Mill Creek Community Church, at the board of supervisors meeting in March. “I think the issue is location, location, location.” The border of Balico’s planned data center campus would be only a half a mile away from the church.

“Robbing Peter to pay Paul doesn’t work”, Campbell told the officials. “We have to be very careful what we ask for. We may get it and we may very well have to pay for it.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts