On a clear day overlooking the inner harbour of Prince Rupert, a northwest British Columbia town home to Canada’s third largest port, chances are you’ll see a spurt of water coming from the surface of the ocean.

“I’ve lived here my whole life and every once in a while, you might get a glimpse of a humpback, but there have been so many humpback whales lately in the harbour, I’ve never witnessed that in my life. It’s a sign that our waters are healthy and abundant,” says Arnie Nagy, a member of the Haida Nation.

Traditionally, Nagy is known as Tlaatsgaa Chiin Kiljuu, or Strong Salmon Voice, because of his years fighting to ensure the survival of the fishing industry and wild salmon on B.C.’s North Coast as a member of the United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union.

He fears that the latest threat to the region’s healthy waters could come from Ottawa. Pierre Poilievre, the federal Conservative leader and the man who might become Canada’s next prime minister — if he can overcome newly minted Prime Minister Mark Carney who is surging in the polls — has long advocated for a west coast energy corridor to ship Alberta oil to Asian markets.

In 2021, Poilievre voted in favour of a private members bill, Bill C-229, that would have repealed B.C.’s North Coast tanker ban to make way for an oil port, saying in a speech to Parliament that he was opposed to “the wrong-headed decision of the Liberal government to ban the shipments of clean, green Canadian energy off the northwest coast of British Columbia.”

In mid-March, CEOs of Canada’s largest oil companies sent an open letter to Poilievre and other national political leaders claiming that “the federal government’s Impact Assessment Act and West Coast tanker ban are impeding development and need to be overhauled and simplified.”

During a recent meeting between Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and Prime Minister Mark Carney, Smith laid out nine non-negotiable demands to avoid what she called an “unprecedented national unity crisis.” One of those demands was for the next federal government to commit to “lifting the tanker ban off the B.C. coast.”

Poilievre called Smith’s demands “very reasonable,” yet he hasn’t offered specifics on his position as Canada heads towards a federal election on April 28, and didn’t respond to a media request from DeSmog seeking to clarify his current views on repealing the ban. Some local First Nations are ready for a political battle if he forms government and moves to allow oil tankers.

“I truly believe people are willing to rise and fight when they see injustice,” Nagy said. “This community is still willing to stand up and defend this place. Governments will do whatever they have to do to weaken that type of connection. And as I’ve always said, I’ll fight till my last breath.”

Devastating Oil Spills

Nagy isn’t a newcomer when it comes to protecting the coast from oil tankers.

When Enbridge proposed its Northern Gateway bitumen pipeline and export project in the mid-2000s, Nagy traveled to Ottawa to speak with cabinet ministers about the devastating impact an oil spill could have on B.C.’s north coast.

That threat includes destroying wild salmon runs that number in the tens of millions and support countless communities and livelihoods along the Skeena and Nass rivers, two of the largest salmon producing rivers in Canada.

A repeat of the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster, when an oil tanker ran aground and ruptured off the coast of Alaska and released over 10 million gallons of crude oil, is one worst-case scenario. But even smaller spills can damage the ecosystem.

In 2016, the Nathan E. Stewart, a tugboat with 110,000 litres of diesel fuel on board, ran aground in the Heiltsuk Nation’s coastal waters near Bella Bella. The spill shut down a robust clam fishery worth $200,000 a year and impacted clam beds, sea cucumbers, abalone and other food sources that have still not recovered in the years that followed.

Despite those risks, political momentum for oil exports on B.C.’s north coast is growing.

In the wake of U.S. President Donald Trump’s tariff war on Canada, which sends about 97 percent of its oil exports to the U.S., conversation on how to get Canadian oil to tidewater for access to Asian markets have refocused on decade-old proposals to ship oil from B.C.’s North Coast.

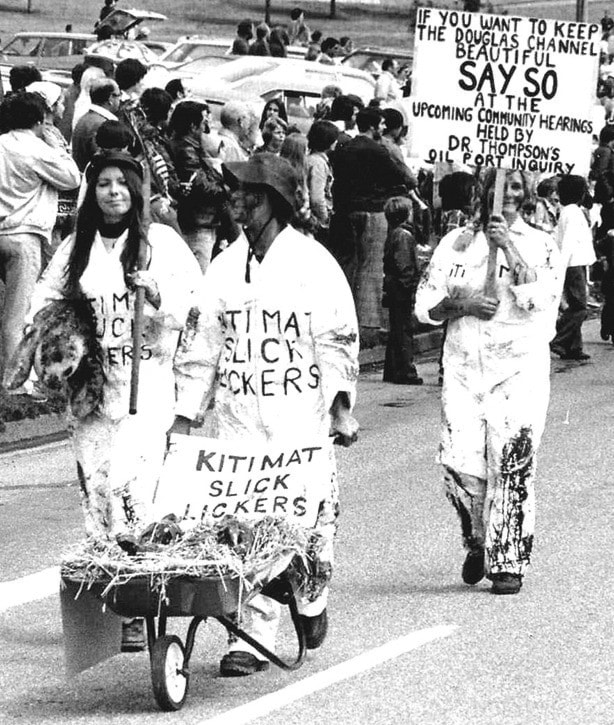

Yet worries about oil port proposals in the region go back to the 1970s West Coast Oil Ports Inquiry, which determined that the sensitive ecology of B.C.’s North Coast should remain off limits to large oil tankers.

The Exxon Valdez disaster, which took place 1,200 kilometres north of Prince Rupert, solidified a voluntary moratorium on oil tanker traffic through B.C.’s central and north coast.

But in 2006, during a boom period for Canada’s oil sands in northern Alberta, Enbridge proposed a 1,177-kilometre (731 mile) pipeline that would carry 525,000 barrels a day of heavy bitumen from Bruderheim, Alberta to an export terminal in Kitimat, B.C. for Asian markets.

What ensued was a decade-long conflict that consumed the region, culminating in a plebiscite in the town of Kitimat where nearly 60 percent of the community voted to oppose the oil port.

“Back then, we were all united against Enbridge, which was the power we had,” says Cheryl Brown, a member of the grassroots organization Douglas Channel Watch, which spearheaded the anti-Enbridge campaign in Kitimat.

Although Stephen Harper’s federal Conservative Government approved Northern Gateway, nearly every coastal municipality and First Nation from Haida Gwaii to Prince Rupert and Kitimat passed resolutions to oppose the ill-conceived project.

In 2016, former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government revoked Enbridge’s permits, effectively canceling the project altogether.

Further solidifying environmental protections for the region, the federal government enacted Bill C-48 the Oil Tanker Moratorium Act in 2019. This legislation prohibits oil tankers carrying large quantities of crude oil from docking along British Columbia’s central and northern coastlines. The act aims to preserve the region’s delicate marine ecosystems and respect the wishes of Indigenous populations.

Poilievre Backs Tanker Ban Repeal

Since then, a Conservative member of parliament from Alberta, James Cumming, has been calling for the repeal of the tanker ban. “Bill C-48 is an overt attack on Alberta’s resource sector,” Cumming said in 2021. “Some have suggested that my bill, Bill C-229, is a waste of a private member’s bill, but frankly, given the absolute sorry state of this country, it is anything but a waste. This bill would right a wrong and fix an incredibly discriminatory piece of legislation.”

Poilievre has in the past wholeheartedly supported repeal of the tanker ban, speaking out in favor of Cumming’s bill in 2021 and saying while he was campaigning to become Conservative leader the following year that prohibiting tankers is an “anti-energy” position.

As the threat of U.S. tariffs intensified in January, opposition to the expansion of hydrocarbon exports through northwest B.C. seemed to be waning among some of the Indigenous community’s most fervent opponents.

On January 21, Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of BC Indian Chiefs (UBCIC) held a press conference during which he seemingly voiced potential support for the Northern Gateway pipeline project through Northwest, B.C., a project he had previously fought against.

“We are staring into the abyss of uncertainty, the climate crisis and the American threat,” Chief Phillip said in Vancouver. “I would suggest that if we don’t build that kind of infrastructure Trump will and there will not be any consideration for the environment or the rule of law.”

As a longtime opponent of the Northern Gateway project, Chief Phillip’s comments were shocking and confusing to many, including Heiltsuk chief councillor, Marilyn Slett, who said at the time that “Our people were on the front lines and fought hard to successfully stop the proposed Northern Gateway pipeline. The environmental risks to our territories were and are too great. Nothing has changed and we are not going to back down.”

Chief Phillip soon walked back his statement saying, “there is no room for fossil fuel expansion”.

Still, the conversation caught the ear of Alberta Premier Danielle Smith who called for the “immediate construction of Northern Gateway.”

‘Remain Completely Opposed’

But that might not be as easy as it sounds.

For one there is the hurdle of the tanker ban, which would need to be repealed before any oil port proposal could be considered. Then there is the issue of local communities and First Nations.

To date, not one North Coast community has supported plans to build an oil port and it would seem those sentiments still hold strong.

Chief Yahaan, also known as Donnie Wesley, represents the Gitwilgyoots Tribe of the Nine Allied Tribes of the Tsimshian Nation near Prince Rupert. Yahaan is an old commercial harvester and led the charge against Pacific Northwest LNG when it proposed to build an LNG terminal over Lelu Island and Flora Bank, a major hub for millions of Skeena salmon.

Yahaan says although unity among the nations has waned since the Northern Gateway days, any attempt to build an oil port that would further threaten the fishing industry would still be met with opposition.

According to Joy Thorkelson, the North Coast representative for the United Fishermen and Allied Workers’ Union, the united front which stopped Enbridge the last time, is still alive and well and would shut down any attempt to reinvigorate the idea of oil tankers traversing these waters.

“We would remain completely opposed to any offshore oil transportation,” Thorkelson said.

Prince Rupert mayor Herb Pond can see the economic value in such a project for his cash-strapped town of 12,000. Yet he acknowledges that “a crude oil pipeline to Prince Rupert is a long shot.” Pond added, “It was a hard push the last time…I think there’s far more likelihood that they will find ways to increase the capacity of the existing Trans Mountain pipeline.”

Down in Kitimat the prospect is much the same. LNG Canada, the largest single energy project investment in Canadian history, is preparing to ship out its first tanker of liquefied natural gas before the end of the year.

Although super tankers will be navigating the narrow Douglas Channel from Kitimat to reach the open ocean, those tankers will be filled with LNG not bitumen, which to the Haisla First Nation is an important distinction.

That nation sees LNG as a means of economic development, which is why the Haisla are not only investing in LNG Canada but also developing their own LNG export facility, known as Cedar LNG, which just received $200 million from the federal government, signalling the Liberals’ support for the project.

Yet in 2019, Haisla Chief Councillor Crystal Smith spoke in favour of the tanker ban, stating in a Vancouver Sun op-ed that, “Haisla are not quick to offer endorsements for any projects when it comes to our territory. We firmly opposed the Northern Gateway bitumen pipeline proposal, which did not meet our conditions or our standards,” she wrote.

“But we’re not talking about oil or bitumen. Coastal GasLink is natural gas, and it should not be confused. A natural gas pipeline will always be a natural gas pipeline.”

Following Chief Stewart Phillip’s remarks on Northern Gateway, the Haisla issued a statement reiterating its opposition to all oil ports in its territories.

“Our position as a community related to a bitumen pipeline through our traditional territory has not changed since previous Haisla leadership and councils opposed the Northern Gateway project over a decade ago. We firmly believe that we can support economic diversification in our territory for the benefit of our members, as well as the country as a whole, without sacrificing our values,” the statement said.

Poilievre Doesn’t Offer Details

Phil Germuth, the mayor of Kitimat, was a councillor ten years ago when the community voted to oppose the Northern Gateway project, even grilling former Northern Gateway CEO John Carruthers during one council meeting about leak detection and spill response.

Now Germuth says if any oil products are to be shipped through his community, he’d like to see them be refined products, not raw bitumen. “If other countries can’t get their resources from us, they’re going to go get them somewhere else, that is a fact,” Germuth said. “If they’re not coming from Canada, then somebody else is getting that opportunity.

Enbridge says it has no plans to re-engage on Northern Gateway, after spending $500 million on a project campaign that essentially went nowhere.

“We currently have no plans to develop Northern Gateway. Our current effort is focused on leveraging our pipeline in the ground and our existing rights of way,” Jesse Semko, spokesperson for Enbridge, said in a statement. “There’s lots of capacity there that is efficient and less disruptive to communities and the environment.”

Still, with 25 percent U.S. tariffs now in effect on steel and aluminum across the country, and 10 percent on energy, the discussions to build pipelines east and west are growing.

Poilievre has been vocal about his intentions to expedite energy infrastructure development, especially under current tariff threats. But he hasn’t directly mentioned reviving Northern Gateway.

In January 2024, when asked during a radio interview if he would support an oil export pipeline and facility on B.C. North Coast, the Conservative leader said he wouldn’t comment on a project that didn’t exist anymore.

“I haven’t heard any proposals for an oil pipeline since Northern Gateway,” Poilievre said. “So I can’t comment on proposals that don’t exist. But we’ll definitely keep an eye on it.”

Instead Poilievre has pledged to repeal legislation he deems obstructive, such as the Impact Assessment Act, Bill C-69, which he argues hampers energy projects.

During an interview with the B.C. news outlet Northern Beat, Poilievre stated, “I will give rapid permits for pipelines so that we can get our energy to market.” Recently, the Conservatives issued a press release calling for the “full repeal” of “the West Coast Tanker Ban.”

But at this point, that might be easier said than done.

Paul Bowles, a retired professor of economics and international studies at University of Northern British Columbia who studied the impact of the Northern Gateway project on local communities says a lot of the market access talk back then is the same discussion today.

However, in today’s economic and environmental climate it would still take about a decade from start to finish to see a major pipeline project come to fruition, given that governments, communities and especially First Nations would all need to agree on a path forward.

But because the opposition was so strong against Enbridge’s oil pipeline a decade ago, Bowles finds it hard to believe it would be a simple task to see it get built today.

“The David and Goliath parallel metaphor is a good one,” Bowles said. “What struck me was that the very strength of being David was the local roots and the fact that it was so local. It was people talking about their local areas, the local watershed, the local channel, the salmon and the importance of the way of life.” And that hasn’t changed.

For those that live off the coast, there is a saying which represents everything they stand for: “When the tide is out, the table is set.” Nagy believes that as long as the coast remains healthy and without oil tankers, communities and villages will survive for another millennia.

“We fought tooth and nail to preserve the coast from the damages of oil and gas exploration tankers, pipelines, and fish farms so things are becoming healthier, and we see it by the creatures that are affected first,” Nagy said.

“In a clean environment, the food chain is undisturbed, and you can witness it. But when you start polluting and damaging all those ecosystems, you get nothing.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts