It was a Friday when the phone rang in the office of a New Zealand-born accountant named William Gaston Walkley. On the other end of the line was Terry Southwell-Keely, deputy chief of staff at the Sydney Morning Herald, who had just received a cable from Standard Oil of California announcing that oil had been found at a place they were calling Rough Range-1.

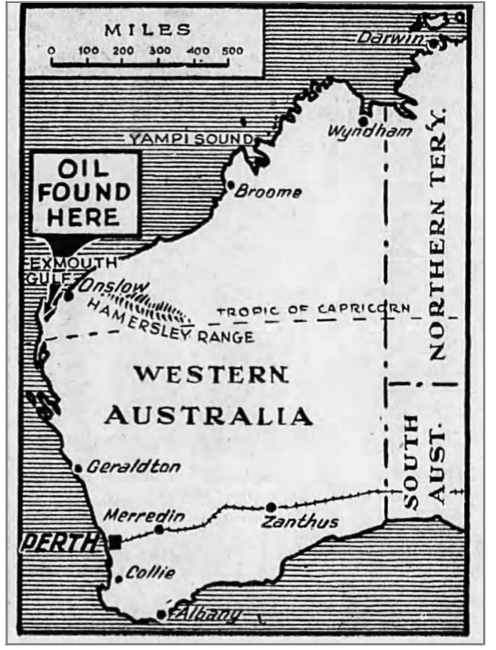

Southwell-Keely had called Walkley to congratulate him on his success. The drill site was out on the far west of the Australian continent, about 1,000 kilometers north of Perth, one of the most isolated capital cities in the world. Getting to this point had taken considerable work, dedication and hustle. Walkley’s company had been scouring the Australian landscape since 1948 for a good place to drill. Now, in November 1953, the first major oil discovery had been achieved and it would give birth to the new Australian industry.

But Walkley — who had been the driving force behind the operation — had no idea that the discovery had even taken place.

“This is the first I’ve heard about it,” Walkley said. “I’ll phone and ring you back.”

The find would go on to make Walkley Australia’s answer to John D. Rockefeller.

New documents obtained by DeSmog from the papers of John W. Hill, founder of public relations firm Hill & Knowlton, show how the New York-based PR agency smoothed the way for a massive expansion of the U.S. oil industry into Australia.

As a globe-trotting influence peddler, the firm was a pioneer in soft power and the dark arts of public relations. It had built its business on making sure the press, government and the public didn’t just get the facts, but received what its clients thought were the right facts. In carrying out this task, Hill & Knowlton would teach local industry how it was done, entrenching public relations practices that continue around the world.

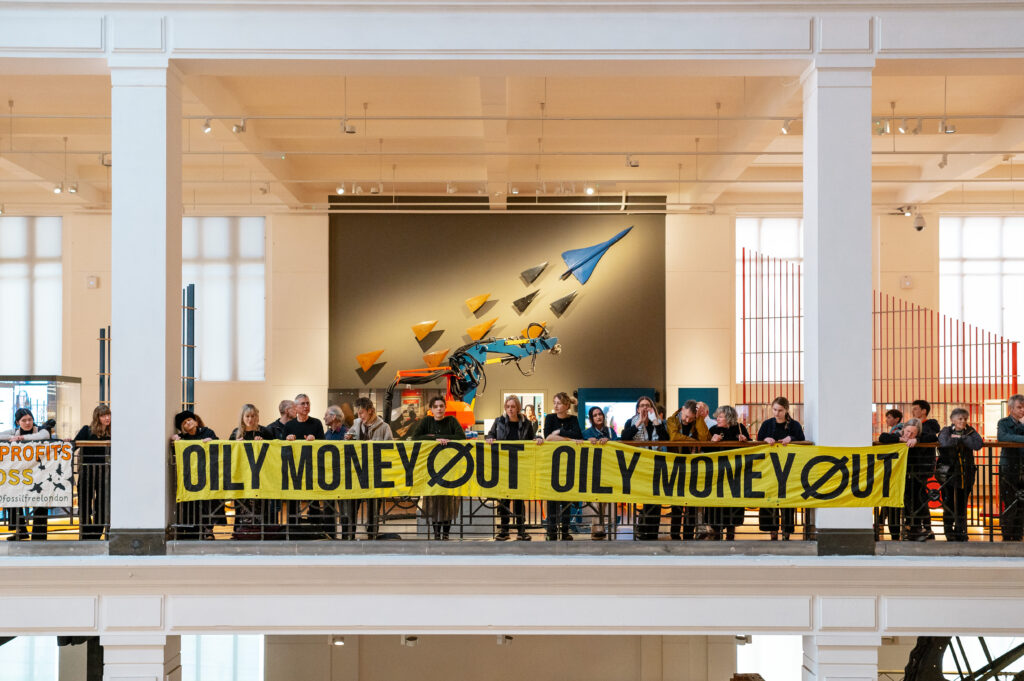

The legacy of this early work by Hill & Knowlton and other firms around the globe endures today, prompting United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres to accuse advertising and PR companies of serving as “enablers to planetary destruction” by having “aided and abetted” a campaign of climate denial and greenwashing on behalf of their fossil fuel clients, the “godfathers of climate chaos.”

“Many in the fossil fuel industry have shamelessly greenwashed, even as they have sought to delay climate action — with lobbying, legal threats, and massive ad campaigns,” Guterres told an audience in New York last June.

“They have been aided and abetted by advertising and PR companies — Mad Men — remember the TV series — fuelling the madness. I call on these companies to stop acting as enablers to planetary destruction.”

“The Company Must Derive Specific Benefits”

The year Walkley moved to Sydney, eight oil wells a day were being drilled in east Texas alone but there was nothing much happening in Australia. The prevailing geological theory at the time was that the ancient Australian landscape was “too old for oil,” which forced the country to rely heavily on fuel imports.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

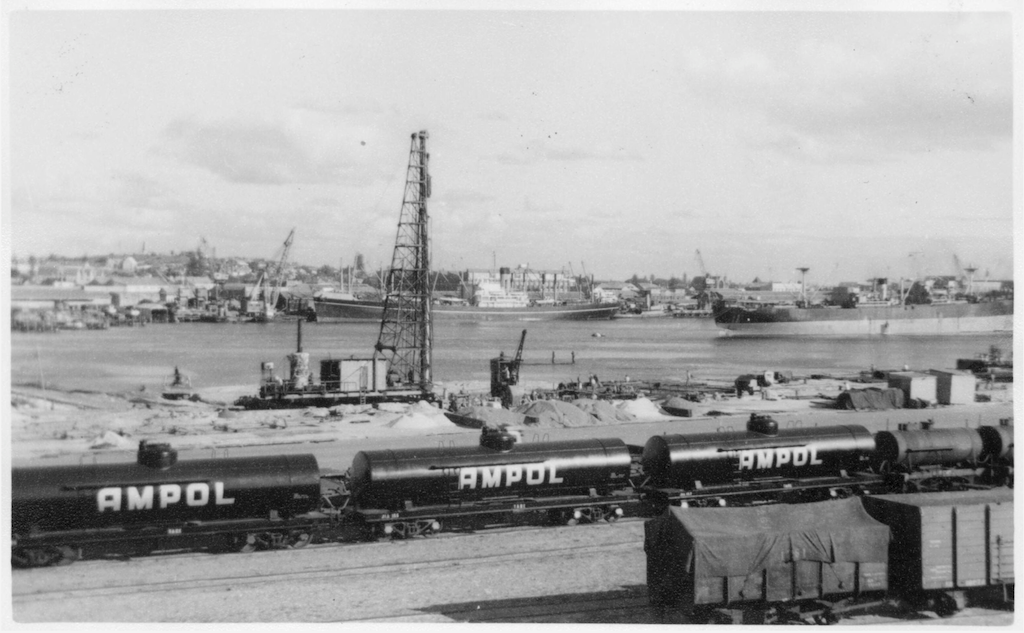

In 1935, Walkley had migrated to Australia from New Zealand to help co-found the Australian Associated Motors Petrol Company (Ampol), which went on to build a network of blue and red-branded petrol stations across the country.

It wasn’t enough, however, to own the nation’s petrol pumps. Walkley wanted the field and the refinery, too. To get it, Walkley had roped a U.S.-based company called Caltex into a joint venture they named “West Australian Petroleum” (WAPET). Ownership of WAPET was split 80-20 between Caltex and Ampol. Caltex was itself a partnership between U.S. oil companies Standard Oil of California and Texaco (both now Chevron).

The Australian government had been more than happy to bless the WAPET project and to encourage the exploration effort. Australia had nearly found itself cut off as Imperial Japan tore through Southeast Asia during World War II and in the aftermath, achieving “energy independence” had become a national priority.

News of the oil find at Rough Range-1 on November 1, 1953, would generate national headlines and revive a flagging search for oil. But in a move that was emblematic of how the U.S. companies saw their Australian counterparts on this new frontier, Standard Oil of California appeared to have kept information about the discovery to itself for a month.

The company had its agents bring back samples to their U.S. labs for testing to make absolutely sure this was a genuine, bona fide oil discovery. When they finally made it public, it surprised everyone — including their business partner, Walkley.

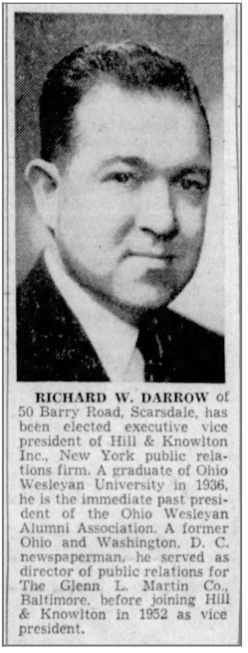

Newspapers across the country carried headlines of a new oil boom, but Walkley reacted with anger as he felt credit for the work went to Caltex and its American operators. Walkley’s personal papers reveal that he blamed one man: Richard ‘Dick’ Darrow.

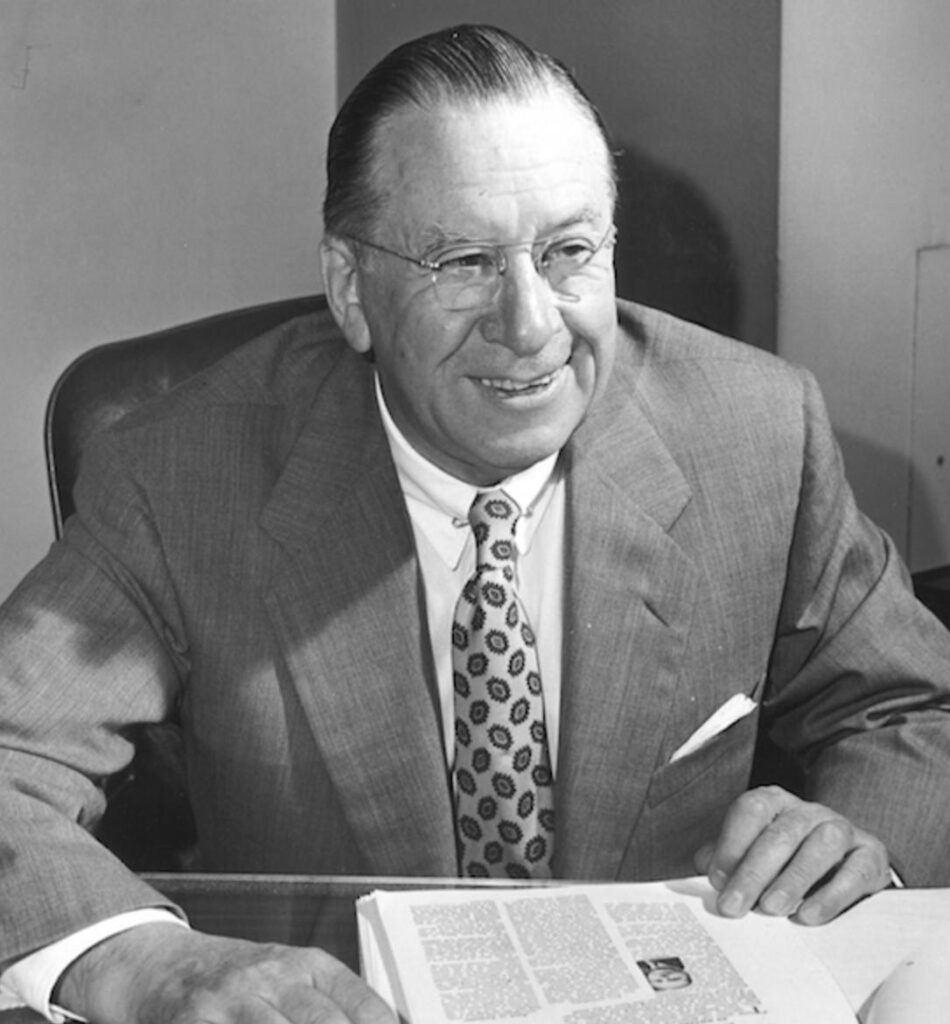

A former U.S. newspaper and radio journalist turned spinner, Darrow served as right-hand man to John Hill, the Hill & Knowlton founder, and later became his successor. Darrow had earned his place in this social circle by serving as a trusted overseer of Hill & Knowlton’s biggest accounts. He had responsibility for clients in the tobacco, oil, gas, and consumer goods businesses, to name a few, and in this capacity he was able to take successful strategies developed among one industry group and apply them to another.

Though it is commonly thought that Big Tobacco wrote the playbook for how to muddy the waters around emerging science, the oil industry had been developing PR strategies to downplay the harms of air pollution for years. By 1953, Hill & Knowlton were masters of that playbook and Darrow was one of its chief evangelists. After the first studies linked cigarette smoke to cancer, Darrow joined a crisis meeting of American tobacco producers at Christmas-time 1953, and later helped them model their industry association, the Tobacco Industry Research Committee, in part on the American Petroleum Institute (API).

When it came to working with oil companies, newly-discovered documents from 1954 show Darrow helping to modernize Texaco’s public relations strategies using insight and experience informed by his work with Standard Oil of California. Darrow would draw on these insights and from Hill & Knowlton’s decades-long PR experience working with some of the U.S.’s most powerful industries, when advising Texaco on how to create events that would allow its executives to schmooze the press, a request the company asked Darrow to treat “as confidential information [that] in no way should be mentioned or indicated to anyone outside those addressed.”

When it came to the creation of scholarship programs, for example, Darrow advised Texaco that Hill & Knowlton’s general policy on education was threefold: “(1) that Industry has an obligation to aid Education, (2) that the program must satisfy the recipient institutions, (3) that the Company must derive specific benefits.”

It was this experience that would influence his advice on similar programs with Standard Oil California and Texaco’s joint venture Caltex in Australia. If Caltex was going to push an expansion into frontier territory like Australia, it was only natural that Hill & Knowlton would position itself to serve as midwife to a new branch of the oil industry. The oil and PR industries had grown up together in the U.S., the evolution of each inextricably connected to the other. Now, as they expanded out into Australia, American PR professionals would use their well-honed methods to help build a modern Australian oil industry.

“A Long-Range PR Program”

In an interview two years before his death in 1977, John Hill recalled how the idea to expand into Australia was conceived when his firm pitched Caltex company executives on the need for a global survey of its operations. It was 1953 and the company had PR problems in Australia, he said. Caltex was already under fire over the price of fuel when it began work on building a refinery just outside Sydney the same year, costing 42 million United States dollars — roughly equivalent to US$494 million or $749 million Australian dollars in 2024 — when it came under attack for its negative environmental impact. Hill & Knowlton, it was suggested, could help address these and other issues if it were allowed to dispatch its agents across the globe to gather intelligence.

“The approaches and procedures utilized in one country do not necessarily apply in another,” the Hill & Knowlton pitch document cautioned. “For that reason a careful study of each key area would be required to develop the basis for judgment regarding the most effective steps to be taken.”

It wasn’t until April 1953 — roughly the same time Texaco paid out its first billionth dollar in dividends to the descendant of a major Texaco financier — that Hill & Knowlton sought a direct arrangement with Caltex to manage its affairs in Australia. Caltex had largely adopted Texaco’s “we-get-along-best-by-telling-’em-nothing” policy in response to public controversies, and Hill & Knowlton was quick to suggest it had cost the company opportunities.

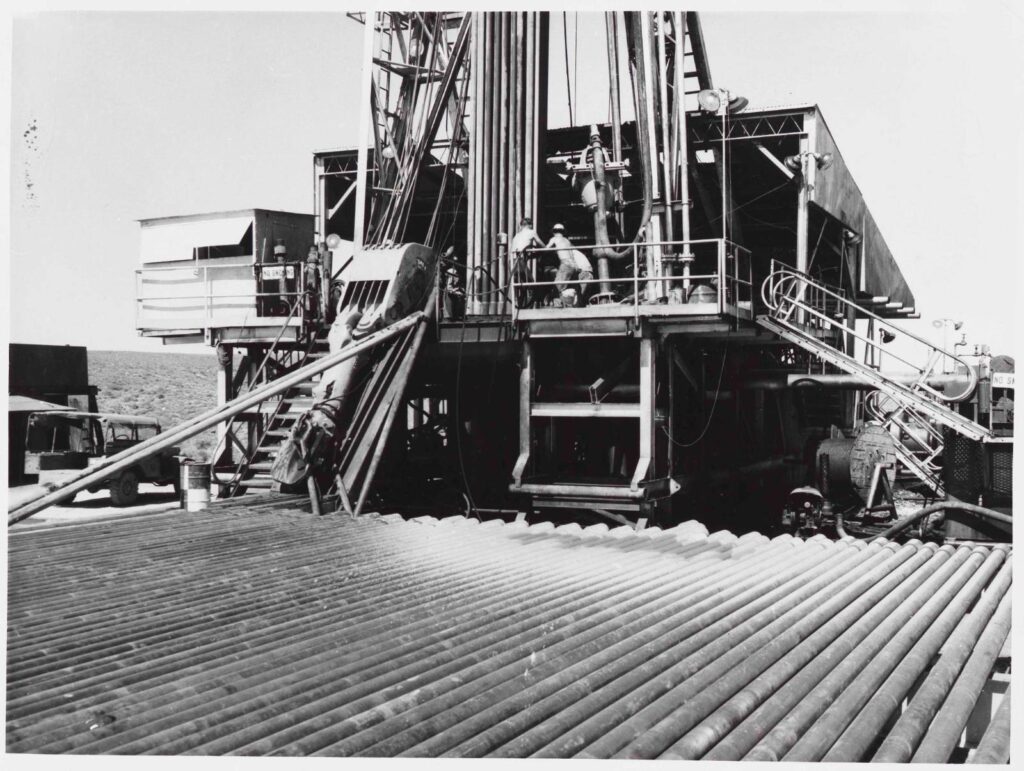

Darrow was Hill’s pick to handle Australia, and the responsibility would place him in the country at Rough Range-1 around the time oil was found. What was supposed to be a three-week trip, however, turned into a three-month tour that left the firm’s executives back in New York short-staffed — Darrow’s clients at Texaco complained bitterly about his absence.

The purpose of the trip, according to an internal memo, was to scope out potential new recruits to represent the firm on the ground in Australia, generate a nimble public relations plan to enable Caltex’s Australian executives to respond to changing circumstances, as well as to “develop machinery and agreed policies for handling any eventualities affecting WAPET” and “protect Caltex public relations interest in Australia generally.”

But there was a problem. Keeping the samples of Australia’s first ‘black gold’ a secret — even from Walkley — combined with Caltex’s habit of running everything through its offices in New York, had inflamed a basic Australian nationalism. Oil meant wealth in any language, but now that it had actually been found it looked like the Americans were coming to claim their plunder.

Darrow’s internal memos attributed the conflict to “a mistaken analysis” by a West Australian government official incorrectly labeling the samples as a mineral called ozokerite instead of petroleum that “led to an impression that there had been a willful holding back of the facts.” Whatever the truth, the damage was done, as public accusations hit the Australian press that Standard Oil of California had simply been trying to manipulate its share price. Now Caltex wanted Hill & Knowlton to fix the mess.

“Mr. Butterworth [Caltex’s vice president of government and public relations] feels that Caltex has a public relations job to do in Australia,” Darrow reported in an internal memo following a meeting with Caltex. “In the face of present agitation becoming more accelerated, however, he believes that it will be necessary to develop a long-range program and lay some groundwork to protect Caltex’ [sic] interest in WAPET.”

According to another internal Hill & Knowlton memo authored by Darrow, part of this long-range PR program would include “material” to be developed in the U.S. “from parent companies, API and other sources which can be utilized by the Australian press, helping to educate the public there on the capabilities of Caltex organization, the true nature of oil development costs and time factors, etc.”

Darrow responded to the situation by creating an information-sharing arrangement and having all WAPET parties agree to simultaneously coordinate any future releases. The smart play, he recognised, was to let Ampol and Walkley take the spotlight and, despite some reservations, Caltex threw its support behind Walkley’s aggressive publicity drive.

And Walkley went for it. Relying on Australian parochialism, a personal touch, and good, old-fashioned insider trading, Walkley pointed to what local reporters called WAPET’s “iron curtain” approach to dealing with the press, an ironic reference to the Soviet-era Iron Curtain, and blamed the Americans for the lack of transparency.

Prior to the find, Walkley had already organized and paid for one chartered press flight out to Rough Range-1, which had “gained Ampol much favorable publicity and continuing good will.” Now that oil had been found, he had plans for a second press trip. Walkley also proposed the company present oil samples to the West Australian cabinet and even Queen Elizabeth II during her visit to Australia that year — a plan Hill & Knowlton encouraged.

But reporting back to Hill & Knowlton management on March 11, 1954, Darrow described Walkley’s practice of encouraging finance reporters to buy Ampol shares, as a means to ensure they were personally invested in what happened to the company, as simultaneously useful and risky, since the firm’s clients were nervous about unrealistic expectations provoking wild swings in the share price.

“The Sydney press has a more active interest in West Australian oil developments than any group outside W.A. itself,” Darrow wrote. “This is traceable, in considerable measure, to Ampol’s active publicity work, its press tour of last fall and Mr. Walkley’s personal acquaintance and regular contact with numbers of journalists. Many of them have bought Ampol Exploration shares.

“The Sydney press, like the Stock Exchange, is frequently stirred by rumor reports predicting new successes — or disasters.”

Insider trading — the misuse of inside information that could have a material impact on the price of shares — was not illegal at the time, but this social compact between the industrialist and the press, though beneficial to Caltex, also made the executives nervous. With Caltex holding majority ownership of WAPET, the Americans generally acted as if they owned it, and would have preferred to ignore their Australian business partners, but Walkley refused to fall into line.

The American executives were aware how bad things could get. They had enjoyed long careers in oil and had lived through booms and busts. Many had witnessed the 1929 stock market crash that had led to the Great Depression. By tying his personal success to the financial wellbeing of the Australian media, Walkley was playing a dangerous game. In a crash, Australia would look for someone to blame and Darrow knew Caltex made for a good villain.

“We are an easy target, being big and being American. Ampol could not, and might not try to, protect the Caltex interest in case of such attacks,” he wrote. “In West Australia, the effect could be serious. The newspapers are adequately powerful and sufficiently steamed up on the subject, to create a public reaction which could make it difficult, if not impossible, for the Government to continue its present degree of cooperation.”

In one report from February 1954, Darrow described Ampol as “an unreliable partner, PR-wise, because of its own ambitions,” darkly concluding that Hill & Knowlton and Caltex “must prepare our own show accordingly” — but even if there was risk, Darrow also recognized opportunity.

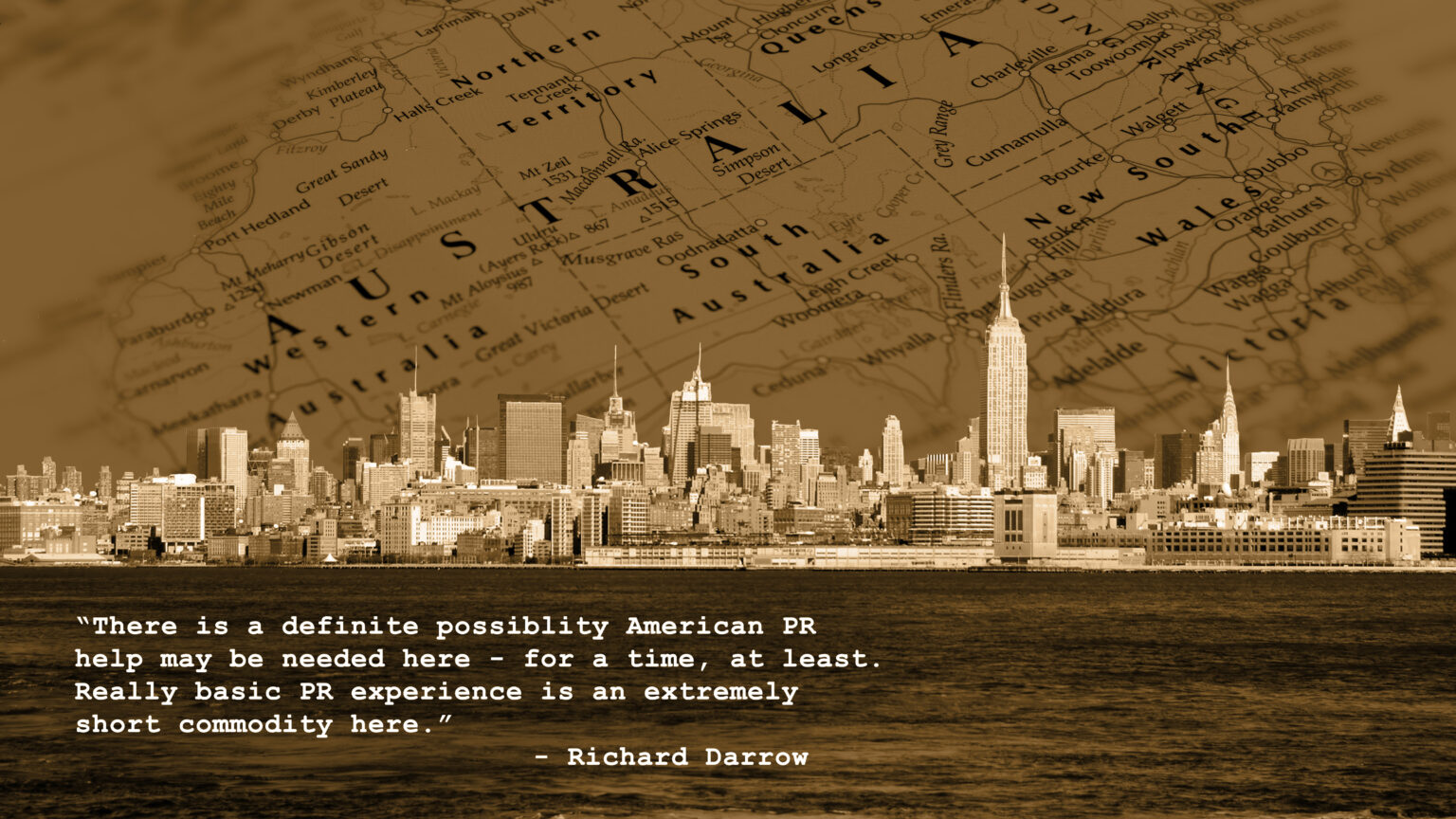

“There is a definite possibility American PR help may be needed here — for a time at least,” he said. “Really basic PR experience is an extremely short commodity here.”

When Darrow’s tour was over, an internal memo dated April 23, 1954, briefed Hill & Knowlton staff on his success: “A few days later, Dick Darrow returned to the office after a 40,000 mile Australia-New Zealand trip for Caltex. His extensive travel in those two countries included an 850-mile overland trek with West Australian newspapermen from Perth to Exmouth Gulf where a Caltex subsidiary is drilling for oil. He blames his sunburn on that journey, plus ‘essential’ seagoing conferences with newspaper editors and an enforced two-day layover in the Fiji Islands for engine repairs.”

As it happened, that same memo also outlined Hill & Knowlton’s creation of the Tobacco Industry Research Committee and the logistical steps it took to support the campaign to spread uncertainty and doubt about the science linking smoking to cancer.

“Small Thinkers at the Australian End”

Australia, in truth, meant little to John Hill. With his firm serving as the vanguard of American capitalism from its office in the Empire State Building, Hill had looked at a map of the world and sized up Australia as a country with no real industrial base 1,300 miles away, on the opposite side of the planet.

Worse, Australians had no vision. At one point the firm’s services would be sought by Australia’s oldest industry association, the Australian Petroleum Exploration Association (APEA), today known as Australian Energy Producers, but a quote for a 5,000 Great British pounds-a-month retainer was rejected by the association as “too dear.” APEA later wrote back asking what Hill & Knowlton “could do for [GBP] £500.”

Australia might be rich in sunshine, but its people were cheap. Hill wanted to be making million-dollar deals in fine restaurants, not haggling over the price of a dollar with a crop of cashed-up ‘bogans.’ In one letter, in April 1955, Darrow also complained about the “small thinkers at the Australian end, unused to public relations and historically inadequate promoters of Caltex interests” who “are tending to press for budget cuts where budget increases are more nearly the right answer.” The more WAPET’s Australian officers sought to cut costs, the more Hill & Knowlton worried that sooner or later, their services would no longer be required, either.

Hill would later write that he “would not shed a tear” if his firm’s Australian branch closed — but Australia mattered to Darrow. In a report back to Hill dated March 14, 1954, Darrow wrote of the potential in the rapidly industrializing country.

“This is a big country which appears likely to grow more and faster than it ever has before, particularly if oil in the West and uranium in central area and west justify transportation and communication which will open up all the other mineral possibilities, etc. known to be present,” he said.

Overall, Darrow had enjoyed his time in Australia, and Hill & Knowlton had already decided to expand into the country in February 1954. It wasn’t until July that year, however, that the company managed to open its Sydney office.

Headed by George E. McCadden, former Australian manager for United Press and “the only American newspaperman based in Australia since 1947”, the firm’s Australian branch initially had three clients: Caltex Oil (Australia), Australian Oil Refining Ltd and WAPET.

From its vantage point in its Sydney offices, the firm would offer a suite of programs, first to Caltex companies and then to others. Hill & Knowlton existed to bend public opinion in their clients’ interest by supplying carefully approved information — so-called “basic facts.” It was these “methods, techniques” the firm planned to export from the U.S. to Australia through a holistic program involving government relations, community relations, charitable activities and sponsorships, school activities (aiming to reach “into the homes of Australians”), employee indoctrination, and efforts to encourage industry cooperation.

One vector of attack for the company was through existing organizations such as the Petroleum Information Bureau (PIB), founded in 1952, and later the Australian Petroleum Exploration Association, founded in 1959.

“We have found in our own work with associations in a number of industries that a public relations committee can be very useful in the job of program planning on one side and program interpretation to the members (you might call it ‘internal public relations’) on the other side,” Darrow advised.

Just over a week later, McCadden replied confirming that he had been appointed Caltex’s representative at the PIB and that he would be “increasingly involved in industry matters” for Caltex.

Hill & Knowlton’s PR operating procedures for Caltex (Australia) explicitly encouraged this activity through “all possible co-operation”.

“It will be helpful to the over-all position of Caltex Oil (Australia) if the petroleum industry develops an adequate public information program. Caltex should give all possible co-operation to that end, including drawing on its own public relations counsel at Sydney and New York for suggestions of how to best accomplish this.”

The firm’s bespoke PR Program for WAPET would also reset Caltex’s relationship with the press by promoting outward transparency and engagement, ensuring carefully targeted information reached “the hands of selected media representatives, including editorial writers, financial editors and news executives.”

As in its U.S.-based work for the tobacco, gas, and chemical industries, becoming the “primary source of information” for the press on subjects vital to its clients’ interests acted as the lodestar for Hill & Knowlton’s Australian operations.

Guided by Darrow and the agency’s New York office, George McCadden set to work executing a program that would prove hugely successful. In the meantime, however, the firm had another problem: Walkley had begun to stir up trouble — again.

“An Extremely Obstinate Inflexible Individual”

From the beginning, Walkley’s chief complaint was that Darrow had been too good at his job and all the credit had gone to Caltex and its American owners for the discovery at Rough Range-1. In retaliation, Walkley unsuccessfully lobbied executives at Standard Oil California and Texaco to pull Darrow from any future work involving Australia.

His anti-Darrow campaign failed but resulted in a compromise settlement that divided WAPET’s PR responsibilities between Ampol’s own public relations firm, Public Relations Associates, and Caltex’s representatives, Hill & Knowlton. For good measure, Walkley hired Terry Southwell-Keely, the Sydney Morning Herald journalist who had broken news of Australia’s first major oil strike to Walkley, to coordinate Ampol’s public relations activities.

With a desk inside WAPET, Southwell-Keely gained unparalleled access into Hill & Knowlton’s operation — a dynamic that prompted the U.S. PR firm to consider Southwell-Keely an industrial spy and earn him Darrow’s loathing. In one later report, Darrow described Southwell-Keely as a “pestiferous candidate for a public relations connection with WAPET through us” and accused him of overseeing a “hatchet job” against a Caltex executive upon the firm’s arrival in Australia.

“[Southwell-Keely] will bear careful watching because he is an extremely obstinate inflexible individual with an extremely narrow view of public relations and a commitment to Mr. Walkley’s outlook on publicity and promotion,” Darrow said.

Otherwise, Hill & Knowlton was happy to promote its arrival on Australian shores as the birth of public relations in Australia. During his Australian tour, Darrow observed that the country’s public relations operators only came in two “varieties”: publicists and political fixers. Hill & Knowlton on the other hand, offered its clients a bespoke all-in-one service. In a 1955 article titled “Australians Adopting American PR Methods,” McCadden bragged to “Editor & Publisher” magazine that growing American investment had brought awareness of public relations as an industry which meant “all Australian firms also are becoming public relations conscious.”

If Australian business wanted access to these skills and insight, the implication went, they would have to go through Hill & Knowlton to get it.

Southwell-Keely, who remained Ampol’s chief of public relations through the 1960s, appeared to draw insight from his time in the firm’s orbit at WAPET. As Belinda Noble, a former Australian journalist who now monitors public relations firms and their work with fossil fuel producers through CommsDeclare, said of Ampol: “They sponsored everything that moved.”

The red-and-blue Ampol branding defined Australia of the post-war period. Following the example of Hill & Knowlton’s U.S. clients, the company gave its name and logo to sports tournaments, artist’s vehicles, radio programs, race car drivers, and symphony orchestras. Walkley even gave his name to Australia’s equivalent to the Pulitzer Prize — The Walkley Awards. Not only did this ensure positive relations with the press, but it allowed him to identify potential candidates to recruit as public relations officers.

“Ampol’s Australian playbook borrows heavily from global Big Oil as described by Antonio Guterres, but leans more heavily to the local ‘good guy’ image where the brand is seen as integral to sports Australians love from surf life saving, to motorsports to rugby league,” Noble says.

“In Australia, Ampol is not perceived as negatively as an Exxon or a Chevron, but that is changing as we recently successfully pressured the Walkley awards to drop Ampol as an award sponsor.”

Despite this trend, Ampol still has seven ad and PR agencies on its books that are ignoring the calls from the UN, by taking fossil fuel money while the earth burns.”

On a per capita basis, Australia is a larger emitter of CO2 than China, Russia, or the U.S. As a major producer of coal and natural gas, the country ranks second in the world for the climate damage caused by its energy exports, according to an analysis commissioned by the University of New South Wales.

“The Hard Fact”

Walkley and Darrow would die the same year, within weeks of each other, but the tricks of the trade they had established would be carried forward through the subsequent decades by their corporate successors.

Caltex counterparts would play an active role in the global disinformation campaign to spread uncertainty and doubt about the science of climate change. As of November 16, 1989, Texaco was a member of the U.S.-based Global Climate Coalition (GCC), corporate America’s primary vehicle for climate denial, which aimed to become “the focal point for business research and policy questions associated with climate change,” inundating the press, politicians, and the public with industry-funded science denying the reality of greenhouse gas-induced climate change. By 1995, executives from both Caltex partners, Texaco and Chevron (formerly Standard Oil of California), served on the GCC board of directors.

Australian fossil fuel producers also participated in this campaign. Like a Russian doll, Australian companies tended to leave most lobbying, government relations, and public relations activity to their industry associations, which were in turn members of larger industry alliances. This allowed them to pool resources and intelligence, and coordinate public messaging — an echo of the strategy Darrow suggested to Hill & Knowlton’s Australia representative, George McCadden, in 1954.

Ampol was a member of the Australian Institute of Petroleum (AIP), which in 1989 produced policy papers actively casting doubt on the science of climate change. AIP was, in turn, one of 14 industry associations which made up the Australian Industry Greenhouse Network (AIGN), a broad industry alliance that mobilized over the next decade to undermine or delay efforts to address climate change, including defeating a proposal for a carbon tax and pressuring the Australian government not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol. AIP remains a member of AIGN.

Hill & Knowlton, Caltex, and Ampol were contacted for comment on this story.

It would be a long time before Australian industry was organized enough to participate in any global campaign to delay climate action. Even with American financial might and know-how, it still took Walkley until 1967 to realize his vision of building a successful oil company.

In April that year, West Australian Premier David Brand turned the valve to officially open the oil flow at Barrow Island, marking the start of WAPET’s commercial operations at the site. During his speech, he heaped praise on Walkley and, in a private letter sent the same day, he tied the success of Australia’s first oil baron to the success of his state.

“No-one can deny the hard fact that away back you had sufficient courage and faith to promote the idea and backed up your belief by going to America and risking your reputation and goodwill by urging overseas interests to invest in the search for oil in this country,” Brand wrote.

“What has happened is history but to my mind the name of W.G. Walkley must always be associated with whatever success in oil production we have in Western Australia.”

They were flattering words, but they ignored how, somewhere behind Walkley, concealed within his considerable shadow, stood Richard Darrow and Hill & Knowlton.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts