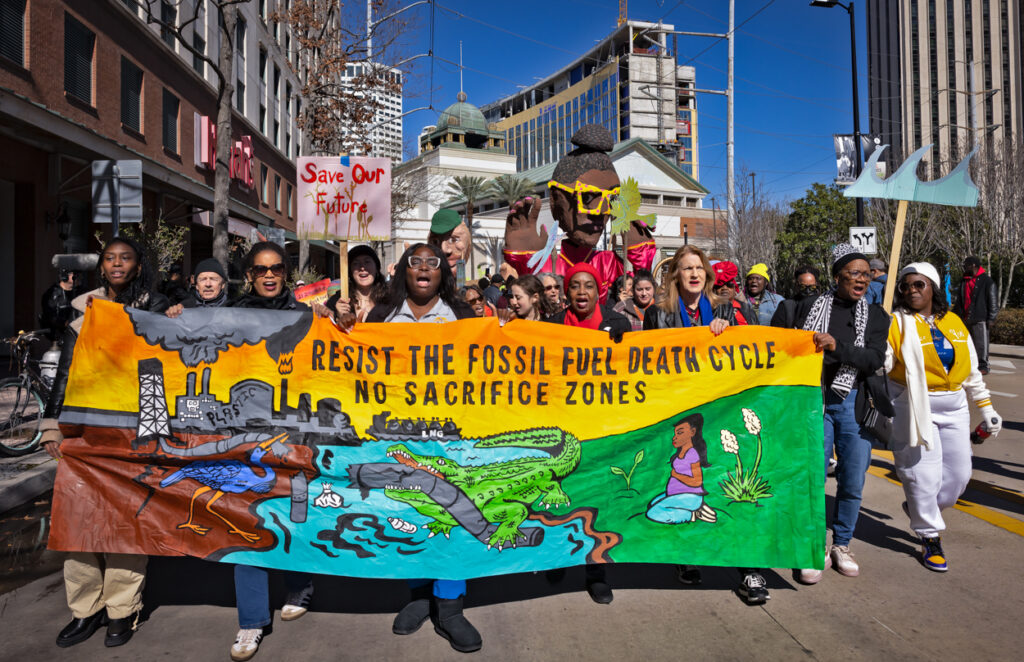

As the year began, the climate movement had its sights set on reining in the sprawling liquefied natural gas (LNG) export industry that’s been transforming the Gulf Coast since 2016. Author and activist Bill McKibben proclaimed “a massive win” early on. But that victory proved to be short-lived. From start to finish, the future of LNG in the United States would take a wild ride in 2024. As the year winds down, we reflect on some of the major moments in policy, the courts, and protest alongside Louisiana-based multimedia reporter Julie Dermansky’s photos of the LNG expansion, the people and places the boom is affecting, and the advocates pushing to limit those impacts.

On January 26, the Biden administration announced a pause on approving new LNG exports to countries without free-trade agreements while the Department of Energy (DOE) updated its economic and environmental criteria for authorizing export approvals. The White House framed the move as part of “the most ambitious climate agenda in history.” After the administration announced the pause, McKibben and others canceled a rally against Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass 2 (CP2) project and other LNG exports that was planned for early February. “Oh, and there’s no need to come to DC for the sit-in next month, which has been called off,” wrote McKibben, celebrating the move. Environmentalists had labeled CP2 a “carbon bomb” for its eventual 20 million metric ton capacity and identified it as LNG project public enemy #1.

But less than six months later, the landscape had changed significantly. Not only had a federal judge in Louisiana struck down the pause on new DOE export applications while the agency finished updating its guidelines, but the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), a federal agency politically independent of the Biden administration, handed the highest profile LNG project, CP2, its essential construction permit with little fanfare.

Meanwhile, U.S. LNG exports continued rising to record-breaking levels from existing facilities along the Gulf Coast. The pause on new LNG export approvals did nothing to turn off the current tap of fracked natural gas, composed primarily of the powerful greenhouse gas methane, that’s being supercooled for easier transport overseas. In fact, the United States, now the world’s top LNG exporter, shipped out four percent more LNG during the first half of this year, during the pause, than the same period last year, according to Clark Williams-Derry, an energy finance analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA).

In September, opponents filed a legal challenge to CP2 arguing that FERC failed to account for the project’s full environmental justice and climate impacts once it is built in Cameron Parish, Louisiana. Elida Castillo, a newly sworn-in representative of her community in Taft, Texas, has witnessed firsthand how living near existing LNG terminals can nearly destroy ways of life — to say nothing of adding the five more proposed or under construction along the Gulf Coast. That’s why Castillo, former Program Director for Chispa Texas, a program of the League of Conservation Voters, has continued showing up on the frontlines of that fight this year, both in the U.S. where LNG export terminals are being built and expanded and in Germany where some of that LNG ends up.

In early December FERC agreed to set aside its approval on CP2’s construction while it updated its environmental impact analysis. “I, along with the fishermen in Cameron, Louisiana, know firsthand how harmful LNG exports are, and see the total disregard they have for human life as they poison our families and seafood,” said Travis Dardar, Indigenous fisherman of Cameron, Louisiana, and Founder of FISH – Fishermen Involved in Sustaining our Heritage. Dardar’s group is among those challenging FERC’s approval of CP2.

The German government recently announced it would shutter a major LNG terminal that imports much of its gas from the United States, calling into question the continued financial and political support for the many new LNG export terminals that continue to go into production along the Gulf Coast.

This year is going out with the Biden DOE’s justification for the LNG export approval pause: its long-awaited study on how shipping natural gas abroad affects American consumers, contributes to pollution, and impacts local communities. Among the agency’s findings was that if the massive build-out kept up, it would inflate utility bills across the nation by an average of $122.54 a year, but rise to nearly triple that for some households. In addition, the report noted, “[m]ultiple studies have found that natural gas production, transportation and export facilities tend to be sited in areas that are disproportionately home to communities of color and low-income communities.”

Environmental and consumer advocates see this report as a potential armor in the courts against President-elect Donald Trump’s promise to swiftly reverse Biden’s pause on LNG export applications.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts