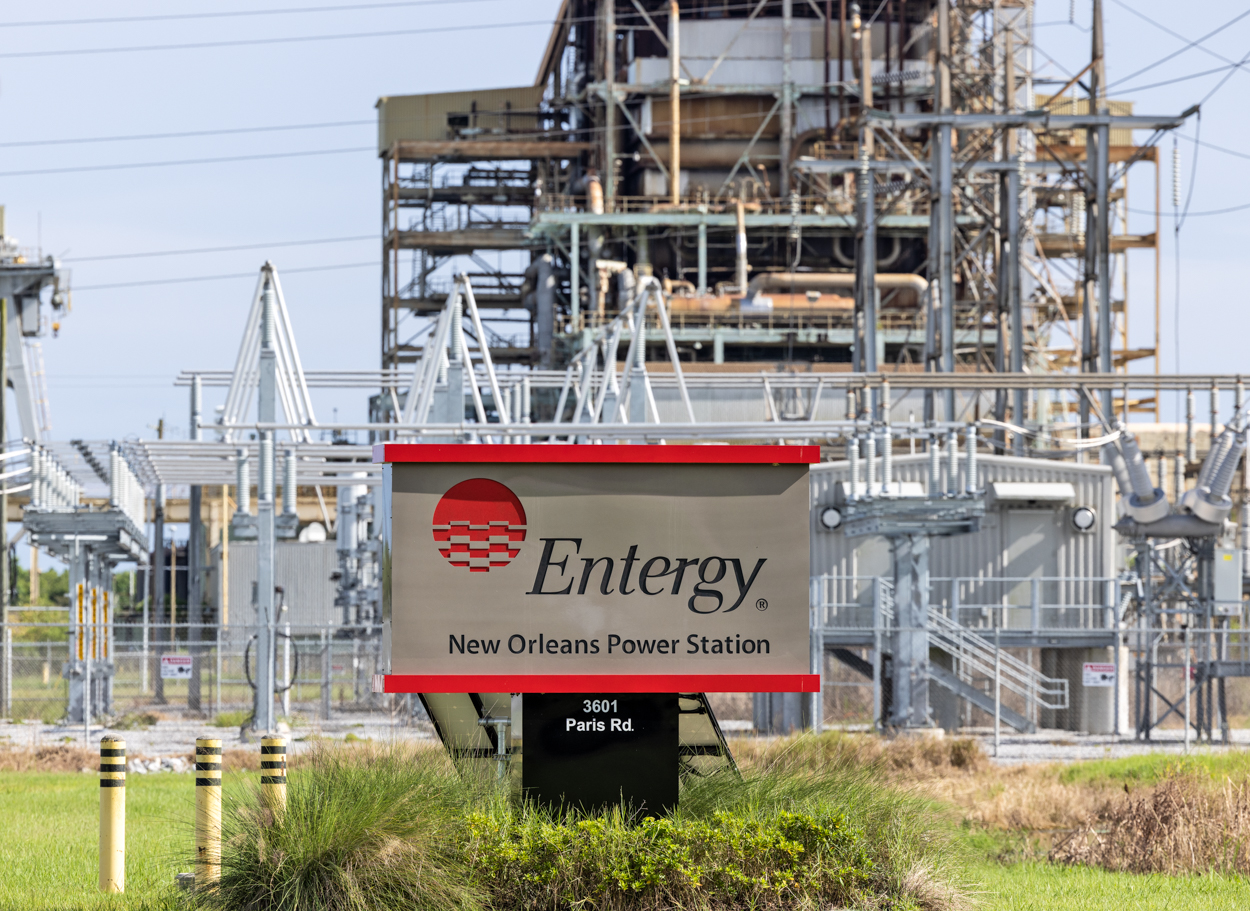

Earlier today, New Orleans City Council unanimously approved the sale of the city’s natural gas distribution system to a private equity firm. Delta State Utilities (DSU), a new subsidiary of Bernhard Capital Partners, will pay $484 million to take over gas distribution systems of Entergy New Orleans and Entergy Louisiana. Bernhard also plans to purchase systems in other states: CenterPoint Energy in Mississippi, and Emera in New Mexico.

Jack Reno Sweeney of the New Orleans Democrat Socialists of America spoke in opposition to the sale at today’s meeting, decrying the City Council’s “shameful capitulation to private equity,” and calling council members’ claims that the sale will allow investment in cleaner energy an “egregious lie.”

Other commenters called the sale a “disaster,” a “charade,” a “tragic parody of governance,” and a terrible Christmas gift, noting that the vote came near the holidays with little opportunity for public engagement. As the motion was approved, cries of “shame” rang out in the chambers.

The sale is a blow to New Orleans ratepayers, as bills are expected to rise on average $31 next year as a result. But it also points to a broader concern: As private equity firms snap up utilities and oil and gas assets, they are largely shielded from local regulation and public pressure to decarbonize.

A Clean Energy Loophole

In 2021, New Orleans passed the Gulf South’s first clean energy standard, legally mandating the complete elimination of fossil fuel use for electricity by 2050. But the mandate applies only to the city-regulated electric utility, Entergy New Orleans, and will not apply to the gas utility being purchased by DSU. Sweeney said the sale creates a massive loophole circumventing the city’s renewable portfolio standard, to Bernhard’s benefit.

The City’s own Office of Resilience and Sustainability (ORS) also opposed the sale. “This deal will place an undue burden on low- to middle-income households, particularly those who are unable to afford the costs of electrifying their homes,” said Greg Nichols, deputy chief resilience officer, in a prepared statement. Nichols added in an email to DeSmog that the City Council could still take actions to address emissions from the gas utility, and that his office is “concerned about DSU’s role in the potential expansion of fossil gas use and infrastructure, which run counter to the City’s long-term climate action goals.”

Councilmember Jean-Paul Morrell said that he doesn’t “take ORS at their word.”

Private equity firms bought at least $25b in fossil fuel assets from the public markets through 2021 and 2022. An October report that examined the energy portfolios of 21 leading private equity firms found that 67 percent of their energy portfolios are invested in fossil fuels, and the carbon footprint of the firms’ investments exceeds the emissions of all global flights taken in 2019.

Private equity firms don’t have the same federal financial reporting requirements that publicly traded companies have, and don’t have state regulators motivated to keep rates low. This “lack of public accountability creates the very real possibility that efforts to curb regional carbon dioxide emissions will become more difficult in the years ahead,” warned Dennis Wamsted, an analyst with IEEFA, in a report last year.

Nichole Heil, senior research and campaign coordinator at the Private Equity Stakeholder Project, says private equity will typically do whatever they can to increase short-term revenue while minimizing costs, and “for things like utilities and where we get our energy from, this has led to spills and accidents.” Shortcuts are especially concerning when it comes to methane gas, which is 28 times more heat-trapping than CO2. Recent studies suggest methane leaks are far more common than previously estimated.

Louisiana is already one of the most burdened states in the country when it comes to energy costs, and prices are predicted to rise further as a result of skyrocketing LNG exports. LNG export terminals are also frequently backed by private equity: One such terminal in Louisiana is already accused of leaks and repeated permit violations.

A ‘Death Loop’ for Pensioners

For low- and middle-income households in Louisiana, the sale is poised to raise rates among families already burdened by energy costs. In 2023, Entergy New Orleans disconnected about 19 percent of the city’s households for bill non-payment. “The people most affected will be the most vulnerable in the city,” Jesse George of Alliance for Affordable Energy told Desmog.

George is also concerned that Delta and Bernhard will be motivated to prolong the use of natural gas in the city. Alex Hurley, a project manager with Global Energy Monitor, likewise warned that the firm will likely be “hostile” to any efforts to get off gas, “if not publicly, then behind closed doors,” he told Desmog.

Monique Harden of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice also commented to the City Council that while businesses and high-income households can afford to electrify, that will leave low-income households to shoulder more of the costs as private equity seeks to extract profits.

DSU is a newly created subsidiary. Private equity firms often create companies this way so they can act as a buffer against any future legal and financial liability, said Dustin Duong, research associate with the Americans for Financial Reform Education Fund, adding that “whatever recourse might need to be taken against Delta in the future, for whatever violation, Bernhard might not be caught in the crossfire.”

Louisiana pensioners will also be affected: This summer, the Municipal Employees Retirement System of Louisiana allocated $25 million to Bernhard Capital Partners Fund III, which is managed by Bernhard. “They’re taking workers’ money and putting it into a project that ultimately harms the very same workers, in a kind of death loop,” warned Duong. “Louisiana workers are paying for their own electricity rates to go up.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts