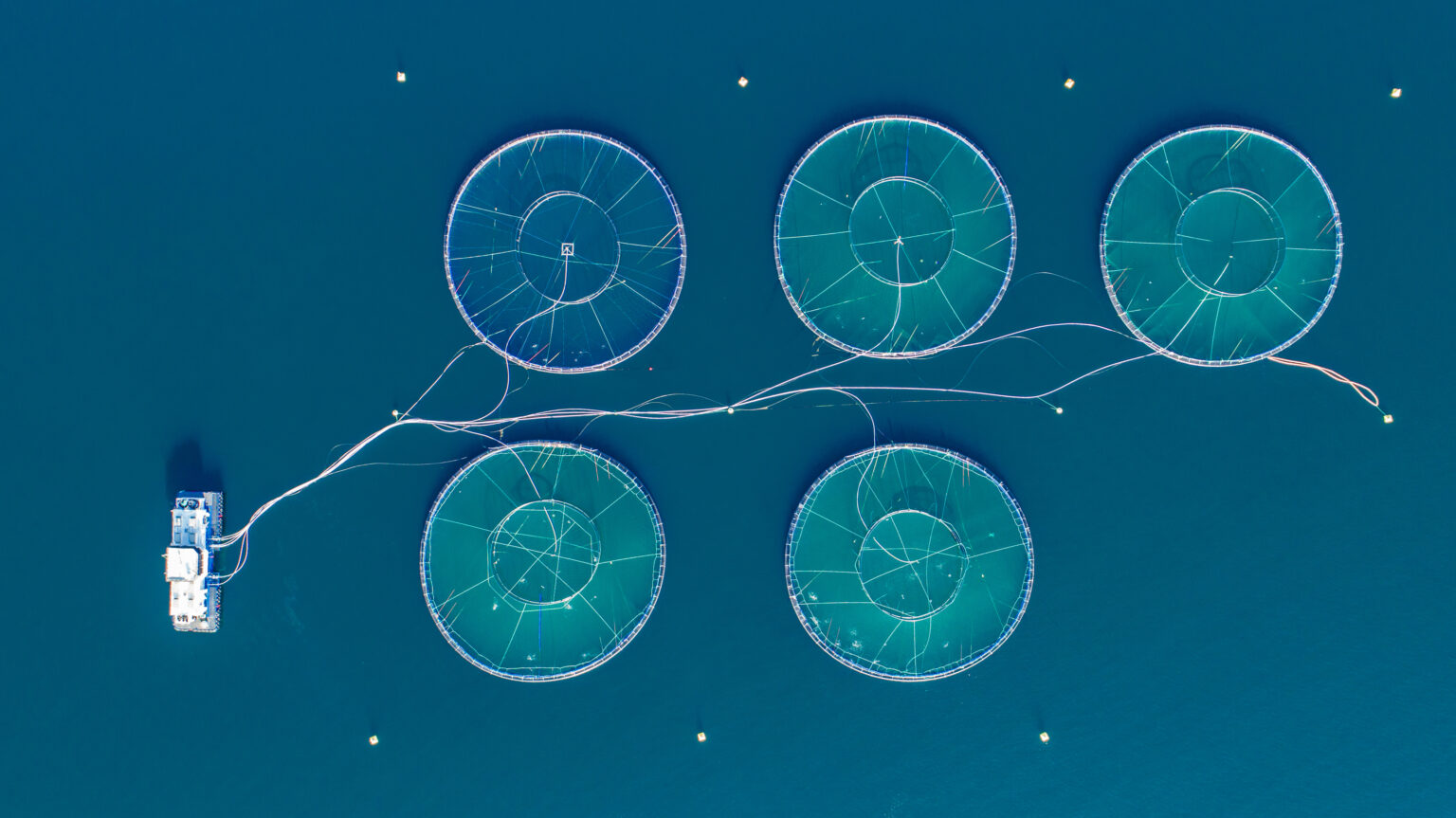

Aquaculture is the world’s fastest growing food sector – one that proponents have long argued can help conserve wild fisheries. The argument goes that farming seafood instead of catching it will provide respite to over-fished species at sea.

Farmed fish themselves also need to eat, however. And some of the world’s most valuable species, like salmon and trout, are fed on fish from the ocean.

In fact, according to a new study, published in October in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances, kilo-for-kilo, carnivorous fish such as salmon and trout eat far more seafood than they provide.

These results suggest that, contrary to the aquaculture’s sustainability claims, the global fish farming industry uses as much as 307 percent more wild fish than previously reported.

A separate review, published in the same journal, found that while the sector has repeatedly claimed to be reducing its hunger for wild-caught fish, it was using “misleading and … often inaccurate” figures, which downplay its demand.

Every year, 23.4 million tonnes of wild-caught small fish – including sardines, sandeels, and mackerel – are ground into fishmeal and fish oil, most of it destined for inclusion in feed for carnivorous farmed seafood like salmon, trout, and shrimp.

The rising demand for fishmeal has been linked to overfishing in India, Vietnam, and other countries where lower fish populations means less food for humans and animals in ocean ecosystems.

“What we understand about carnivorous fish farming has relied on the most optimistic data,” said Jennifer Jacquet, an environmental scientist at the University of Miami and co-author of the study. “The picture is not as rosy as previous studies led us to believe”.

Read DeSmog’s new database entries on salmon feed producers Cargill Aqua Nutrition and Skretting, which, together with Mowi and Biomar, produce most of the world’s salmon feed.

Depleting Wild Fisheries

To determine how much wild fish was consumed by farmed fish, a research team led by Spencer Roberts, a doctoral student at the Rosenstiel School in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy at the University of Miami, estimated the quantities of wild caught fish –and cereal crops – needed for different types of aquafeed, based on publicly available data.

Roberts and his team determined that farmed salmon consume up to six times their body weight in wild fish by the time they go to market, while shrimp eat up to one and a half times their body weight in wild fish. The figures challenge industry claims that both farmed species consume less, or equal to what they produce.

Salmon and shrimp are some of the most popular farmed marine animals among consumers in the Global North. In 2022, global salmon sales were worth more than $21 billion, while the shrimp market is estimated at almost $74 billion in 2024.

The impacts of these industries have been repeatedly underestimated by those in the sector, according to the second study, co-authored with researchers from environmental advocacy group Oceana.

This team, led by Patricia Majluf, an environmental scientist with the Center for Environmental Sustainability at the Cayetano Heredia University, reviewed scientific literature on the use of wild-caught fish in aquaculture. The researchers found that contrary to the industry’s claims that it is helping to “feed the world”, aquaculture is depleting wild fisheries that would otherwise be used by coastal communities.

Aquaculture is “primarily being used to produce high-value, globally traded seafood that benefits only the few who can afford it,” the researchers stated.

Both studies concluded that aquaculture almost never produces more calories or nutrients than it consumes, contradicting the industry’s claim that large-scale fish farming is essential to nourishing a growing human population.

When contacted by DeSmog, IFFO, a trade group that represents the interests of the marine ingredients industry, declined to comment directly on the findings of the two recent studies.

“On net, it is very clear that the industry destroys food”, said Roberts. “It’s not feeding the world, but actually starving people”.

Competition for Food

Campaigners have long accused the aquaculture industry in West Africa of competing with human food needs, driving overfishing, and threatening fishworkers’ livelihoods.

In Mauritania, Senegal, and the Gambia, fishmeal and fish oil factories funnel nutritious small fish away from the local population. The small fish provide essential – often irreplaceable – micronutrients like zinc and iron, and provide employment to tens of thousands of women fish workers. Pressure on these already overexploited and declining stocks puts them at risk of collapse.

As fed-aquaculture production continues to grow, demand for fishmeal and fish oil increases. Between 2010 and 2020, fishmeal and fish oil factories expanded exponentially along the West African coastlines. During the same period, fish consumption per person in Senegal halved, with quantities of highly nutritious pelagic fish (the main local seafood) dropping from 16 to 7 kilos per year.

Much of aquaculture’s fish oil demand is driven by rich countries’ hunger for farmed salmon, which consumes 44 percent of the world’s fish oil.1According to calculations made by DeSmog based on a 2022 report published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and a 2022 study.

A portion of this is sourced from North-West Africa, where salmon giant Mowi and salmon feed producers Cargill Aqua Nutrition, Skretting, and Biomar all sourced fishmeal and fish oil in 2023, according to company reporting.

Norway, the world’s largest salmon producer, is the destination for most North-West African fish oil. Feedback, a food and farming campaign group, estimated that the volume of West African fish fed to Norwegian salmon in 2020 could have instead provided up to 4 million people with a year’s supply of fish sufficient to meet their nutritional needs.

“Farming of species such as salmon and seabass is not only damaging ocean ecosystems, it’s also hurting communities that rely on fishing for their livelihoods, and harming food security in some of the poorest regions of the world,” according to Feedback industrial aquaculture campaigner Amelia Cookson.

In response to a request for comment, Mowi told DeSmog via email that it no longer sourced from West Africa.

Skretting told DeSmog that it sourced from the region, and stated that it was actively involved in multiple stakeholder initiatives with the aim “to improve the environmental and social impacts of our operations”.

“Skretting is committed to continuously drive improvements across its supply chain,” it said. “For maximum impact, we need to work together and find solutions through collaboration with partners throughout our value chain”.

Skewed Numbers

According to both studies, the aquaculture industry has downplayed its impacts on wild fish stocks by using estimates that rely on averages that calculate feed use by all seafood farming, rather than just carnivorous species.

Since non-fed farmed species like mussels and oysters subsist on microscopic organisms naturally occurring in the water, including different farmed species in calculations makes it appear as if carnivorous farmed species are consuming less fish per kilo produced.

In addition, industry figures only account for the number of fish harvested to be turned into marine ingredients. But according to the study led by Roberts, many more fish are killed as by-catch or in a process known as “slipping”, when vessels that catch a higher number of fish than their allowed quotas allow unwanted fish escape – but up to 99 percent of escaped fish die in the process.

Another issue with industry figures concerns the industry’s treatment of trimmings. These are fish parts such as heads and tails, offcuts from fish caught for human consumption that are usually characterised as waste, and therefore excluded from calculations of wild fish usage.

For example, the global fishmeal and fish oil lobby group IFFO calls trimmings an “environmentally friendly way of recycling waste products”, and says that over half of fish oil and a third of fishmeal globally are made from trimmings, rather than whole fresh fish.

However, Roberts’ study found that in some regions, due to rising demand for fishmeal, the market for trimmings is so profitable that it is driving fishing, and is not a byproduct.

The sector has historically defended its demand for wild-caught fish by arguing that these are not fish eaten by people anyway, but that is not always the case. In Senegal, according to the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, the industry is using fish previously consumed by local communities. Globally, up to 90 percent of fish used in fishmeal and fish oil could be directly eaten by people.

“Aquaculture producers [hide] behind crafty accounting to downplay fish farming’s impact on wild fish populations,” Cookson from Feedback said.

Aquaculture’s Impacts on Land

With the seafood industry growing, even efforts to reduce the amount of wild fish needed per kilo of fish farmed have come at an environmental cost.

The sector has been increasing its use of plant-based ingredients in feeds, in order to replace some of the fishmeal and fish oil used. Crops used in fish feed include rapeseed, soy, maize, and wheat farmed in countries around the world.

But while this switch might help limit overexploitation at sea, it adds to demands on agricultural land and water supplies.

The volume of crops eaten per kilo of farmed salmon doubled between 1997 and 2017. And with the industry trebling production, this means that six times more crops were used in total each year by the end of the period, Roberts and his team found.2Calculations by DeSmog using supplementary data in Roberts et al. 2024. Salmon production in 1997 was at 1,200,000 tonnes, using 650,000 tonnes of crops (each tonne of salmon consumed about half a tonne of crops). In 2017, salmon production was at 3,500,000 tonnes using 3,700,000 tonnes of crops (each tonne of salmon consumed about one tonne of crops).

In 2020, three of the world’s four largest salmon feed producers – Cargill, Biomar, and Skretting – sourced soybeans linked to recently deforested land in Brazil, according to data compiled by the environmental group Trase.

Advocacy organisations such as Rainforest Foundation Norway have criticised the aquaculture industry’s increasing volume of crops in fish feed and their links to deforestation and wild habitat destruction.

Skretting told DeSmog: “In 2023, 8 percent of our total soy purchases were untraceable or originated from high-risk regions without any certification, whereas 92 percent of our soy purchases in 2023 were compliant with our intermediate goals […] We are committed to sourcing 100 percent deforestation-free by the end of 2025”.

Biomar, and the Federation of European Aquaculture Producers (FEAP) did not respond to a request for comment.

- 1According to calculations made by DeSmog based on a 2022 report published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and a 2022 study.

- 2Calculations by DeSmog using supplementary data in Roberts et al. 2024. Salmon production in 1997 was at 1,200,000 tonnes, using 650,000 tonnes of crops (each tonne of salmon consumed about half a tonne of crops). In 2017, salmon production was at 3,500,000 tonnes using 3,700,000 tonnes of crops (each tonne of salmon consumed about one tonne of crops).

- 1According to calculations made by DeSmog based on a 2022 report published by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization and a 2022 study.

- 2Calculations by DeSmog using supplementary data in Roberts et al. 2024. Salmon production in 1997 was at 1,200,000 tonnes, using 650,000 tonnes of crops (each tonne of salmon consumed about half a tonne of crops). In 2017, salmon production was at 3,500,000 tonnes using 3,700,000 tonnes of crops (each tonne of salmon consumed about one tonne of crops).

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts