This story is the fifth part of a DeSmog series on carbon capture and was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

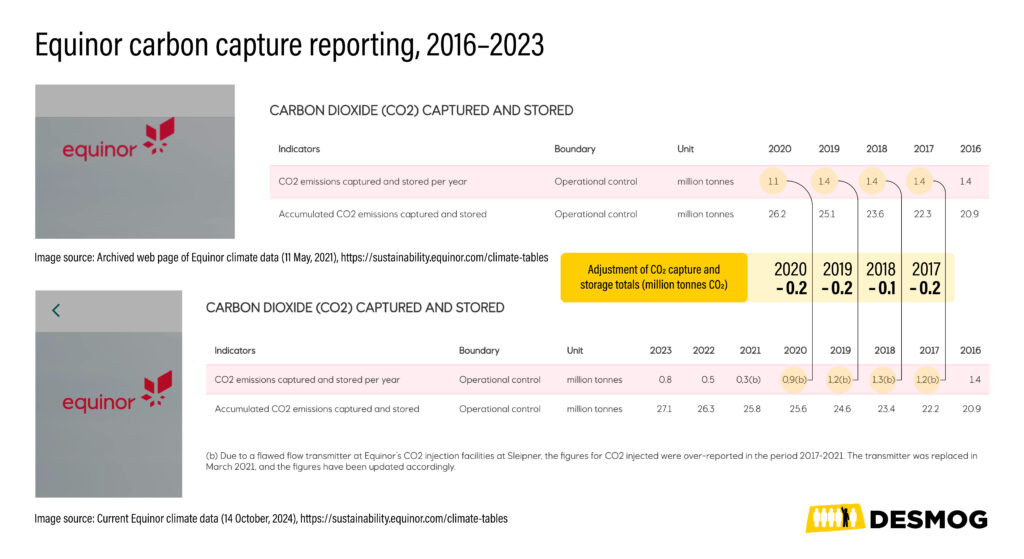

Norwegian oil and gas company Equinor has admitted over-reporting the performance of a flagship carbon capture and storage project by about 28 percent due to defective monitoring equipment, underscoring risks associated with plans to scale the technology as a climate solution, DeSmog can reveal.

In a footnote in its latest sustainability data, Equinor said a malfunction in equipment used to measure the amount of gas flowing through a pipeline at its Sleipner gas field in the North Sea had caused it to over-report the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) stored from 2017 to 2021.

“Due to a flawed flow transmitter at Equinor’s CO2 injection facilities at Sleipner, the figures for CO2 injected were over-reported in the period 2017-2021,” the footnote said. “The transmitter was replaced in March 2021, and the figures have been updated accordingly.”

Equinor did not quantify the extent of the over-estimates in the footnote on Sleipner. The 28-year-old project is often cited by carbon capture advocates as proof that it’s technically feasible to trap and store large quantities of CO2 underground.

A DeSmog review of publicly available company data conducted in October suggests that Equinor captured and stored a cumulative total of 1.6 million tonnes of CO2 at Sleipner from 2017-2019, compared to its initial estimate of 2.1 million tonnes — implying that it had previously over-reported the amount of gas stored during that three-year period by about 30 percent. [See note on methodology at the end of this story].

At the time, a lack of comparable data made it harder to estimate how much the company may have over-estimated CO2 capture at Sleipner in 2020 and early 2021, although partial numbers suggested that the figure was also about 30 percent.

In November, DeSmog obtained more precise data from the Norwegian Environment Agency, which collates figures supplied by the oil and gas industry.

Those new numbers showed that Equinor had reduced its estimate for the amount of CO2 stored from 2017 through March 2021 to 2.115 million tonnes from 2.700 million tonnes — a downward revision of 28 percent.

“Based on the assessment of available data from other relevant systems, we have no indication of measurement errors before this error in 2017, and none after the faulty equipment was replaced,” said Equinor spokesman Gisle Ledel Johannessen. “The injection system has been fully operational in the entire period. As an example, the last 5 years we have injected 99,7% of the CO2 that has been captured on Sleipner into the ground.”

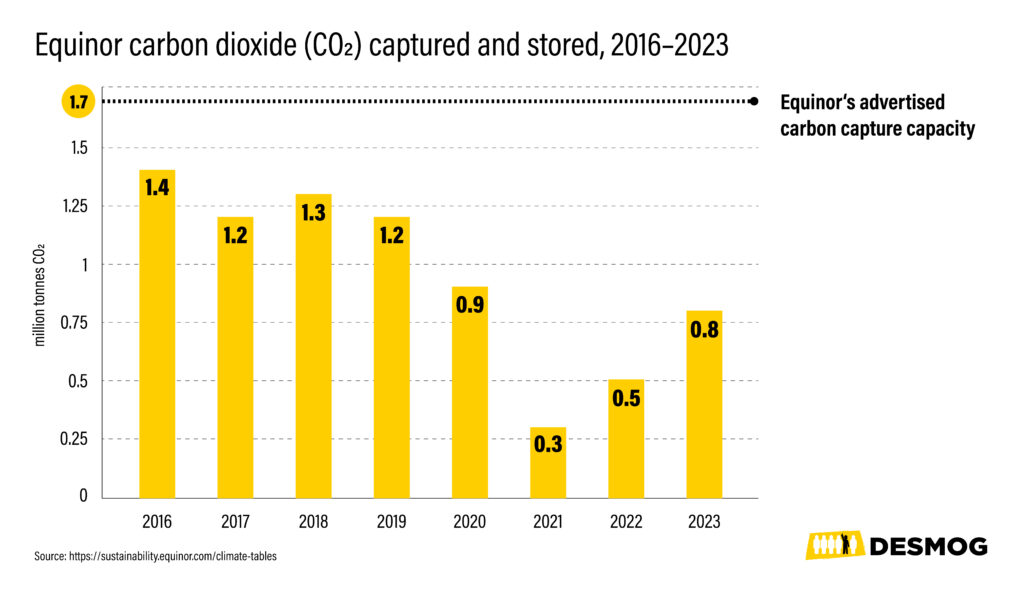

Until last month, Equinor said on its website that it captures about 1.0 million tonnes of CO2 at Sleipner each year, and a further 0.7 million tonnes from a similar project at the Snøhvit gas field in the Barents Sea. Figures in the company’s sustainability reports, however, suggest that it is routinely failing to achieve this level of capture.

In 2021, with the Snøhvit facility shut down due to a fire at the associated Hammerfest LNG (liquified natural gas) plant, Equinor captured and stored a total of 0.3 million tonnes of CO2, all at Sleipner, according to its annual sustainability report — less than 20 percent of the total advertised on its website. The figures subsequently obtained from the Norwegian Environment Agency yielded greater precision, putting the amount of CO2 captured at Sleipner in 2021 at 0.260 million tonnes.

Last year, with both CCS sites operational, Equinor captured and stored a total of 0.8 million tonnes of CO2, according to the company’s online sustainability data — about half the advertised total. About 0.106 million tonnes of this CO2 was captured at Sleipner, according to the Norwegian Environment Agency data.

The drop in CO2 capture and storage could be linked to waning natural gas production at Sleipner, said Grant Hauber, a researcher for the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis think tank, who wrote a 2023 report on Norway’s carbon capture projects.

“As production from the Sleipner field declines, the quantity of CO2 being handled declines,” Hauber told DeSmog in October. “Equinor has not disclosed if there is a practical minimum where the processing facilities are no longer effective in handling CO2.”

Johannessen, the Equinor spokesman, has since confirmed to DeSmog that the decline in Sleipner’s CO2 storage was due to reduced gas production at the field.

Separately, Hauber’s 2023 report showed that Sleipner and Snøhvit encountered unforeseen issues with CO2 storage, with Equinor having to drill a new CO2 injection well at Snøhvit between 2010-2016, and unpredictable underground CO2 migrations at Sleipner.

Johannessen said that the projects “have both had a long record of successfully storing the captured CO2 volumes, with nearly continuous injection histories” and that their track record was “excellent.”

“The CO2 stores at Sleipner and Snøhvit are globally recognised CCS projects which for several decades have demonstrated CCS as an important technology for storing CO2 safely and permanently under the seabed,” he added.

Troubled History

While Equinor estimates that 99.7% of CO2 captured at Sleipner was successfully injected over the past five years, the downward revision of overall capture amounts at Sleipner and Equinor’s frequent failure to run its two carbon capture projects at full capacity echo a long history of missed targets, cost-overruns and economic problems at CCS projects in North America and Australia. These challenges have convinced many environmental groups that fossil fuel companies primarily see the technology as a cover for continued expansion of oil and gas production, rather than a viable tool for curbing emissions on a global scale.

Nevertheless, Equinor has leveraged its experience at Sleipner and Snøhvit to position itself as a key player in the UK’s plans to ramp up carbon capture capacity with the support of £22 billion of subsidies announced by the new Labour government in October.

The Norwegian company is also partnering with France’s TotalEnergies and the UK’s Shell on the Northern Lights carbon storage project in the North Sea — a key component of the European Union’s target to boost carbon capture to meet its climate goals.

Equinor says that it aims to increase its CO2 storage capacity to 30 to 50 million tonnes by 2035 from projects planned in Norway, the UK, Denmark and the United States. That would require a massive build-out: Today, the world’s combined CCS capacity amounts to about 50 million tonnes of CO2 a year.

Although the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) sees a significant roll-out of carbon capture to meet net zero targets, it has also warned of the dangers of over-reliance on the technology.

“The [fossil fuel] industry needs to commit to genuinely helping the world meet its energy needs and climate goals — which means letting go of the illusion that implausibly large amounts of carbon capture are the solution,” wrote Fatih Birol, IEA executive director, in the introduction to a report on clean energy transitions for oil companies published in November.

Oslo-based think tank Bellona, which also sees a role for carbon capture, emphasised the importance of companies providing reliable capture data.

“Bellona believes that reliable monitoring, reporting and verification is important. It is clear we need CCS, and we need to be able to trust that the system works as it should,” said Olav Øye, the organisation’s senior advisor for industry and climate.

Releasing CO2 into the Atmosphere

Equinor (then known as Statoil) began capturing carbon in 1996 at the CO2-rich Sleipner field in the North Sea to reduce its exposure to a new Norwegian tax on CO2 emissions.

The company promotes its carbon capture operations as a key part of its clean energy strategy, with CCS featuring in its advertising campaigns. Nevertheless, Equinor’s records indicate that its Sleipner facility did not capture and store the majority of the field’s CO2 emissions in recent years, but rather released them into the atmosphere.

While CO2 is captured and stored during the processing of natural gas at Sleipner, a larger amount of CO2 is emitted from gas-burning turbines which power the drilling operations at Sleipner and several nearby gas fields.

Emissions from operations at the Sleipner field amounted to about 0.658 million tonnes of CO2 in 2023, according to Equinor’s sustainability reporting. That same year, in 2023, Equinor captured and stored a combined total of about 0.106 million tonnes of CO2 at Sleipner, implying that the Sleipner facility released more than six times the CO2 that it stored.

Company data suggests Sleipner may also have been one of the dirtiest offshore projects in Norway last year, when measured in terms of “CO2 intensity” — the amount of carbon dioxide released from oil and gas production per unit of energy.

Equinor lists the combined CO2 intensity the production area which includes Sleipner and the nearby Gudrun gas field at 19.1 kilograms of CO2 per barrel of oil equivalent, which was the third highest among 19 listed oil and gas production sites operated by Equinor in Norway. In April, Equinor announced a plan to electrify drilling in the Sleipner area, which the company says will reduce yearly emissions by about 0.160 million tonnes of CO2, which is equivalent to about a quarter of the 0.658 million tonnes of CO2 emitted at Sleipner last year.

The Snøhvit gas field has also proved highly CO2-intensive, even when its carbon capture facility has operated at maximum capacity, due to the energy needed to liquefy natural gas for export at the associated Hammerfest LNG facility on Melkøya Island.

Equinor reported 0.890 million tonnes of CO2 emissions from its Hammerfest LNG facility last year, making it the company’s third most polluting project overall, behind its Mongstad oil refinery and Oseberg gas field.

In August 2023, the Norwegian government approved the “Snøhvit Future” project, which includes plans to electrify operations at the LNG export plant with an approximate $1.2 billion investment announced from Equinor and project partners Petoro, TotalEnergies, Neptune Energy and Wintershall Dea.

The developers say that the new infrastructure will reduce emissions by an estimated 0.85 million tonnes of CO2 per year by 2030.

While additional CCS infrastructure was considered to reduce emissions at the LNG export plant, Trond Bokn, head of project development for Equinor, wrote in an article in the company’s online magazine that expanding carbon capture at Snøhvit to meet that target would have cost at least $3.4 billion — about three times the electrification plans.

While Equinor says that carbon capture would be too costly for the LNG export facility at Snøhvit, the company aims to apply the approach in other sectors in Norway and abroad, where government subsidies are available.

In September, Equinor inaugurated the Northern Lights offshore carbon transport and storage project near Bergen, its joint venture with TotalEnergies and Shell, which it says will store 1.5 million tonnes of industrial CO2 emissions a year from a cement works and waste-to-energy plant on the Norwegian mainland.

The majority of the project is financed by $1.19 billion in funding from the Norwegian government and an additional $141 million grant from the European Union’s Connecting Europe Facility fund.

Even if Equinor reaches its 2035 goal of storing 50 million tonnes of CO2 a year — a more than 60 times increase over the 0.8 million tonnes of CO2 the company captured and stored in 2023 — it would only offset about a fifth of the 262 million tonnes of CO2 emitted from its operations and burning its oil and gas last year, according to company data reviewed by DeSmog.

Note: This story, published on 28 October 2024, was updated on 18 December 2024 to reflect information subsequently obtained from the Norwegian Environment Agency and Equinor that showed the company over-reported its CO2 capture rates by about 28 percent, and not 30 percent as suggested by DeSmog’s analysis of previously available company data. There are additional figures and details throughout.

An earlier version of the story also included the following statement: “According to Equinor’s 2023 reporting, Sleipner emitted 658,000 tonnes of CO2, 41 times higher than Gudrun’s 16,000 tonnes — despite only producing about a third more natural gas — meaning the Sleipner field’s individual CO2 intensity would be much higher if reported individually.”

Equinor has since informed DeSmog that the Sleipner’s higher CO2 emissions intensity, caused by burning gas to generate electricity, would be at least partly offset by its role in providing elecricity to enable production at other fields, including Gudrun. DeSmog was therefore unable to determine the quantity of CO2 emissions attributable to gas production at each individual field in the Sleipner area, though the story’s finding that the area’s combined CO2 intensity is the “third highest” among Equinor’s 19 reported oil and gas extraction sites in Norway stands.

Methodology and Sources

Equinor initially reported that it had captured and stored a cumulative total of 4.2 million tonnes of CO2 over 2017-2019 according to a tally of yearly data from the company’s online sustainability data (see initial report: “Carbon Dioxide (CO2) Captured and Stored”; see current report for comparison).

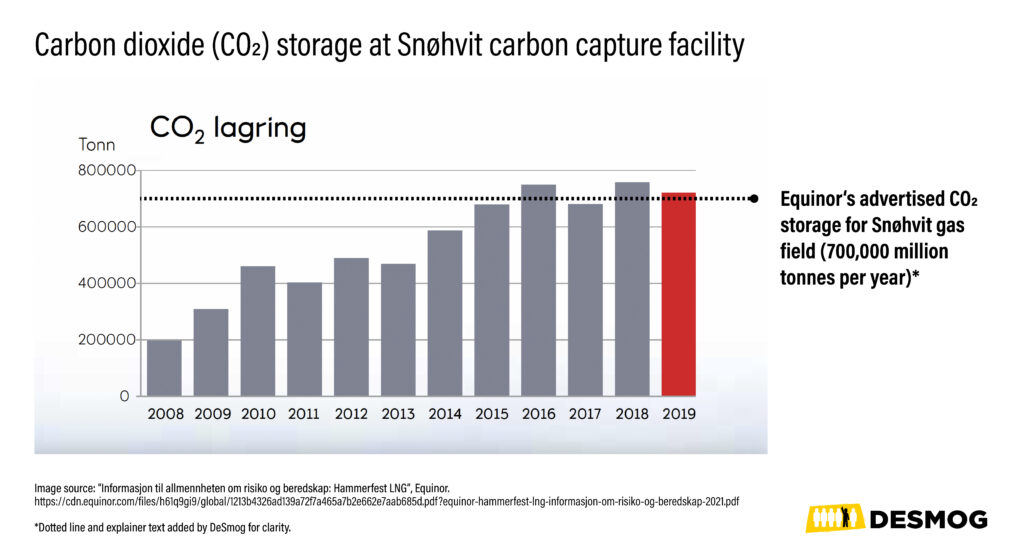

The company does not break down the amount of CO2 captured and stored from its two active CCS facilities at the Sleipner and Snøhvit gas fields in its sustainability data, but DeSmog was able to estimate the amount using a separate Equinor document related to the Snøhvit project. (see: “Informasjon til allmennheten om risiko og beredskap: Hammerfest LNG”, page 4).

A chart in this document (“CO2 Lagring” or “CO2 Storage”) indicates that Snøhvit was operating at a capacity of about 0.7 million tonnes of CO2 a year over the period 2017-2019, which equates to a cumulative total of 2.1 million tonnes of CO2 stored. Subtracting that figure from the total of 4.2 million tonnes of CO2 that Equinor reported storing during the period gives the remainder stored at Sleipner, also 2.1 million tonnes.

Equinor later revised its estimate for the cumulative total of CO2 stored over the period 2017-2019 for both sites down to 3.7 million tonnes, with all changes attributed to the flawed flow transmitter at Sleipner. That implies that Snøhvit would have still captured a total of 2.1 million tonnes of CO2 during this period, but Sleipner would have only captured a revised 1.6 million tonnes.

The difference between the 2.1 million tonnes of stored CO2 initially attributed to Sleipner and the revised figure of 1.6 million tonnes suggest that Equinor initially over-reported CO2 storage by about 31 percent during the period 2017-2019. Given that the company provided figures rounded to the hundred thousand, it was impossible to arrive at a more precise percentage.

DeSmog was not able to obtain specific CO2 capture and storage totals for Sleipner or Snøhvit in 2020, when Equinor initially reported 1.1 million tonnes of total CO2 stored, before revising that figure to 0.9 million tonnes. However, the total amount of over-estimation attributable to Sleipner — 0.2 million tonnes of CO2 — suggests a similar percentage of over-reporting as the period 2017-2019.

Equinor’s sustainability dataset also indicated over-reporting for Sleipner in early 2021, but DeSmog was unable to find comparable data to calculate the size of the overestimate. The company appears to have revised the totals sometime in 2022, based on a comparison of its yearly sustainability reports.

Equinor’s webpage “CCS: Carbon capture and storage — making net zero possible” says that the company captures and stores about 1 million tonnes of CO2 a year at Sleipner and its webpage “Snøhvit” indicates that the company captures and stores about 0.7 million tonnes of CO2 a year at the field.

Equinor’s yearly emissions total of 262 million tonnes of CO2 was calculated by adding up the company’s Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 emissions reported in its 2023 sustainability data.

DeSmog shared its calculations with Equinor. The company did not respond before publication of this story on October 28.

In November, DeSmog obtained more precise capture and storage data for Sleipner from the Norwegian Environment Agency, as supplied to the regulator by Equinor.

Originally Reported CO2 Capture and Storage at Sleipner:

2017: 679,000 tonnes

2018: 602,894 tonnes

2019: 648,521 tonnes

2020: 660,270 tonnes

2021: 307,223 tonnes (of which 108,906 tonnes were stored from 1/1/21 to 25/03/21)*

*The 108,906 tonnes of CO2 amount for 1/1/21 to 25/03/21 was calculated by DeSmog from available data (total over-reporting for 2021 was 47,276 tonnes of CO2, all of which was attributable to the period 1/1/21 to 25/03/21, added to the adjusted total of 61,632 tonnes of CO2 for 1/1/21 to 25/03/21 provided by the Norwegian Environment Agency).

Adjusted Reported CO2 Capture and Storage at Sleipner

2017: 557,468 tonnes

2018: 508,775 tonnes

2019: 481,647 tonnes

2020: 505,509 tonnes

2021: 259,947 tonnes (of which 61,632 tonnes were stored from 1/1/21 to 25/3/21)**

**Figures were provided by Norwegian Environment Agency for both the entirety of 2021 and the period 1/1/21 to 25/3/21

The original amount of CO2 reported over the period 1 January 2017 through 25 March 2021 was 2,699,591 tonnes.

The adjusted amount of CO2 reported over the period 1 January 2017 through 25 March 2021 was 2,115,031 tonnes.

Therefore, the amount of CO2 over-reported between the period of 1 January 2017 through 25 March 2021 was 584,560 tonnes, which reflects a 28 percent (27.63 percent) downward adjustment in the CO2 storage reported at Sleipner over that period.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts