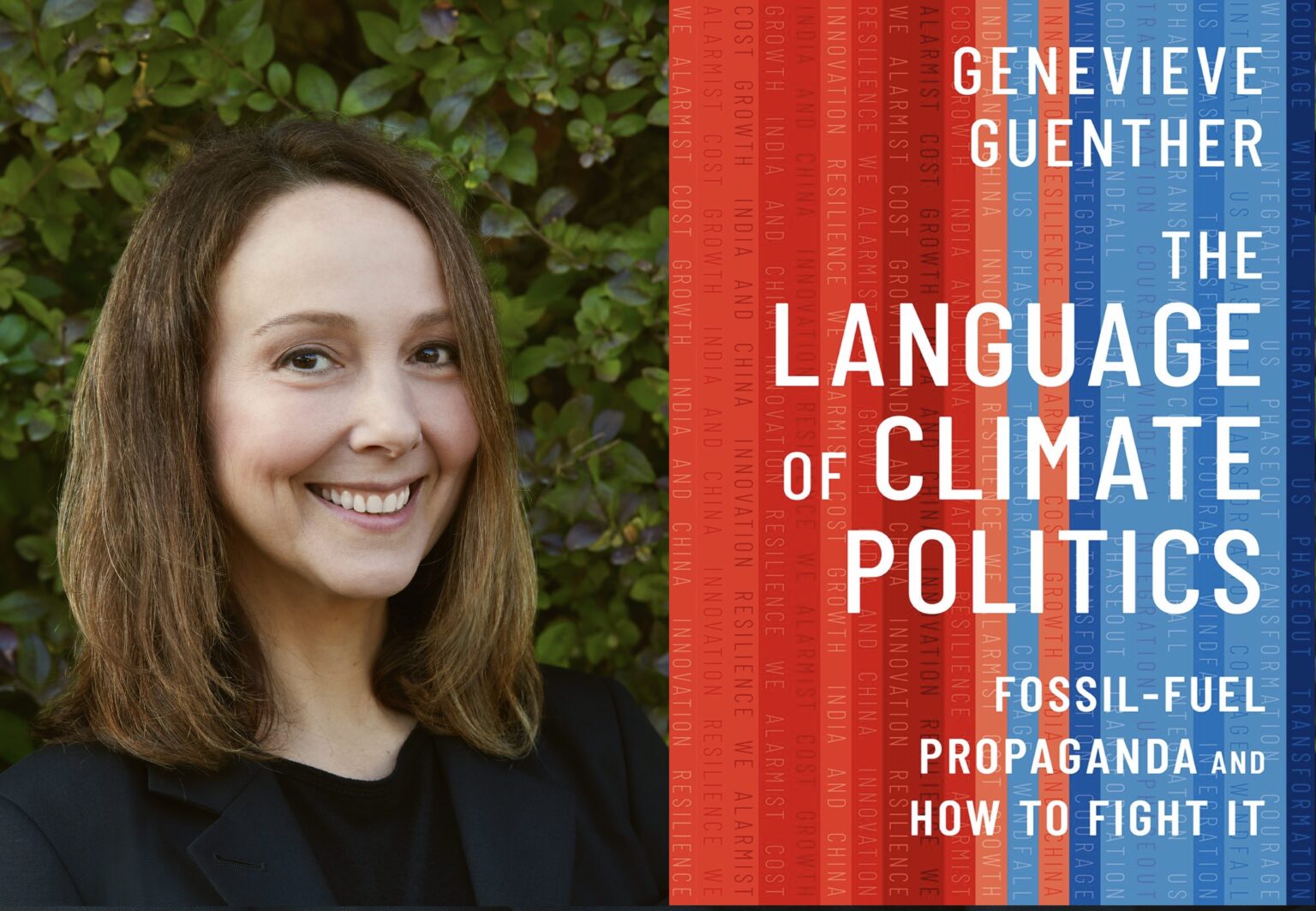

The idea that the climate debate can be neatly divided into two competing camps — with Republican deniers on the right and Democratic advocates on the left — is one of the many myths that Dr. Genevieve Guenther takes on in her new book The Language of Climate Politics. The reality, according to Guenther, a climate communications expert and founder of the advocacy group End Climate Silence, is that fossil fuel industry talking points permeate the political spectrum, contributing to a mainstream consensus that producing ever more oil, coal and gas is fine even as the planet burns.

One way to blunt this “new climate denial,” as she calls it, is better and more effective language that puts a phase-out of fossil fuels at the center of the climate action agenda. In an exclusive interview with DeSmog, Guenther explains how oil and gas companies weaponize the language of climate advocates, why it can be a waste of time trying to engage with Fox News viewers and what needs to happen to put truly transformative climate action at the top of political agendas everywhere.

This conversation has been edited slightly for length and accuracy.

Geoff Dembicki: From a big picture perspective, why does language matter when it comes to climate politics?

Genevieve Guenther: Well, language matters because in the broadest sense, it influences the way that we think, and how we think influences the way that we act.

The more focused answer is that there is a new climate denial circulating now, and it’s not exclusively focused on attacking science and trying to create doubt over the reality of climate change. What it’s trying to do is justify the continuance of the fossil fuel system. It does so by creating false and dangerous beliefs that we can keep using coal, oil and gas while still dealing with climate change. That new denial is created and maintained by language.

Is there an example from your book you can highlight?

We have to hit net-zero emissions within decades. Yet banks, politicians, business leaders and honestly most Americans, Republican and Democratic, support continuing to use fossil fuels. You see this in the polling, that most Americans support greater climate action. But if you ask them about fossil fuels specifically, even a full 48 percent of Democrats in some polls say we should keep using fossil fuels moving forward.

So what’s creating and sustaining these beliefs is a narrative that I dismantle and reframe in my book. And the narrative goes something like this:

Climate change is a problem, but it’s just something that we’re going to be able to manage. And to call it an existential threat is alarmist. It’ll cost too much to decarbonize our economy. And really, what we have to focus on is economic growth, because wealth is one of our greatest protectors against climate devastation. What we need to do is focus on fomenting innovation and increasing our resilience. And in any case, we shouldn’t act unilaterally because emissions are still rising in both India and China.

You spend a lot of time in the book examining and critiquing people who ostensibly care a lot about the climate crisis, including Democrats and even other climate change writers. Why is that?

The reason this narrative that I mentioned earlier is so entrenched, and the reason that it’s actually shaping the status quo, is that it seems to be something that both sides believe. Part of the reason for that is that the language of climate advocates has been weaponized by fossil fuel interests. There are advocates who are sincerely trying to promote climate solutions, but who still actually advance the same fossil fuel ideologies as the climate deniers.

For an example of that kind of person, I would point to William Nordhaus, the Nobel Prize-winning climate economist, who was a very early mover in the climate space. He was one of the first economists to recognize that climate change was real and that climate change was dangerous. But because he held a host of economic assumptions that were sort of grounded in the ideologies of the fossil fuel economy, he built a model that showed that we should keep using fossil fuels until the climate heats up by three degrees Celsius, because that would be economically optimal for the United States. Subsequent research disputed this. But here was a man who essentially handed talking points to Republican presidents justifying the U.S. pulling out of international climate targets because he told them, quite literally, that it was not in America’s economic interest to try to phase out fossil fuels and halt emissions as soon as possible. (Nordhaus denied his work is influenced by the ideology of the fossil fuel industry when contacted by DeSmog. We’ve included his response at the end of this post.)

This is the dynamic that I think is really important. It’s not just that there are ridiculous lies coming from the Right. There’s a mainstream narrative about how we’re supposed to solve the climate crisis. And that narrative is incorrect and dangerous.

Given all of that, who would you say is your ideal reader for this book?

Anyone who writes about climate or does climate organizing or researches climate or is a policymaker trying to write climate policy — everyone in the climate movement. But my ideal reader is a Democrat who knows that climate change is real and is concerned or even alarmed about it, but who has learned most of what they know about the climate crisis and its resolution through the mainstream news media.

The one institution that has done the most to advance this new climate denial, I argue in the book, is the mainstream news media, either because they are silent about the climate crisis and they fail to describe the dangers of climate change adequately, or because they actually use as sources the fossil fuel interests who are spreading this new climate denial.

What kind of political possibilities could you see opening up if more people disavowed this denial?

My theory of change that underlies the book is that there is currently very broad, but very shallow, support for climate action in the American electorate. And there is only minority support for phasing out fossil fuels entirely. And we’re not going to get any action on climate change until that changes. That’s one part of the theory.

The second part of the theory is that trying to address the so-called moveable middle and wake up people who are disengaged about climate change, or doubtful about it, or even just curious but who have it very low down on their sense of priorities — trying to wake those people up is kind of a waste of time. Because what we really need to do is move people who are already concerned. What we need to do is move the concerned into the category of the alarmed, and then mobilize the alarmed to become actively engaged in the climate movement. That’s what’s going to lift climate change to the top of the political agenda.

How do you get more people activated on climate change when people like Trump continue to dominate the news cycle?

There’s no way that enough effective climate language is going to filter through the New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and The New Republic to make a difference. We need organizing. We need new assumptions in academia. We need departments of climate change studies. We need a court system that’s on our side. We’re not going to do any of that without changing false beliefs. But at the same time, without the right messages, all of those other things will not happen. We need to talk about climate change without echoing our enemies’ rhetoric and normalizing their disinformation.

Even when there are strong social movements on climate, the oil and gas industry loves to co-opt their language. How do we defend against that?

Let me turn this question around. What do the words ‘net zero’ and ‘decarbonization’ imply? Do they imply that we have to phase out fossil fuels? No. They imply that we can keep using fossil fuels and build technologies that will enable us to balance out our emissions or somehow decarbonize extraction and combustion.

So I’m very aware that language is being co-opted every second. I have developed language in the book that cannot be co-opted, and that will not be weaponized, because it keeps the phase-out of fossil fuels at the center of the climate politics agenda. This language is specifically about how fossil fuel interests are happily destroying the only planet known to support life in order to make a little bit more money for a couple of decades.

And what about rightwing media? It seems like one of Fox News’ primary goals is to ridicule and discredit any kind of climate action.

When they see something they don’t like, they’re not shy about attacking it all. They’re good at it. Rightwing media is really a problem. And there’s nothing like it on the left, because the left still thinks of itself as a reality-based community and they don’t have a media propaganda arm for their party’s policies. That said, I am less worried about how Republicans and Fox News watchers feel about something like the Green New Deal, and more worried about how mainstream, affluent Democrats and independents might feel about it. To me, the larger problem is a residual commitment to neoliberal economic solutions like a carbon tax or carbon removal or bipartisanship.

We’re always going to have enemies, right? There’s always going to be another side that’s really opposed to saving the world. We need to transform the world, and there are going to be people who are opposed to that. So we need to understand that that’s the situation we’re in. We’re in a kind of life-or-death struggle. We need people who are 100% on board with the transformation of the world on our side, or else we’re never going to have the strength or vision that will overcome the money and the entrenched influence of the fossil fuel industry and its allies.

Response from William Nordhaus: “I have been advocating activist climate policies for decades, particularly the use of proven tools like cap and trade and carbon pricing. These have been derided by many environmentalists as ineffective with no viable substitutes. It is too easy to point the finger at researchers, where the real issues are structural, with weak international governance (the COP), poor instruments (such as subsidies), along with myopic political figures. The first step toward effective climate policies would be to devise an effective international governance structure such as the one that has been described as a climate club. Without strong governance, we will see decades more of a process where nations talk loud and carry no sticks at all.

“As to the work resting on the ideology of the fossil fuel industry, that is not only a hallucination (in the AI sense) but also nonsensical. Carbon pricing at levels I have proposed would not only curb emissions sharply but also reduce the value of fossil fuel companies. Fossil fuels constitute 82% of primary energy today, with only a small decline in that share over the last two decades. We need strong and effective carbon pricing policies to make a significant dent in that number.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts