Environmental groups are teeing up a legal challenge to new Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rules on pollution from chemical and plastics plants, citing concerns the EPA relied too heavily on lowball industry estimates as it sized up the risks to people’s health posed by ethylene oxide (EtO), chloroprene, and other toxic air pollution.

The EPA just announced the new rules in April, saying they’re intended to “significantly reduce” dangerous pollution from chemical plants and some plastics plants.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

But the Environmental Integrity Project, Earthjustice, Sierra Club, California Communities Against Toxics, Air Alliance Houston, and others filed suit this week in the federal D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, with attorneys for the groups telling DeSmog they believe the EPA’s rules remain too weak.

“The EPA’s underestimation of the risks posed by chemical facilities puts nearby communities in grave danger,” Earthjustice attorney Deena Tumeh said in a statement announcing the litigation. “By downplaying ethylene oxide emissions, the EPA fails to protect public health adequately.”

When contacted by DeSmog, the EPA declined to comment, citing pending litigation.

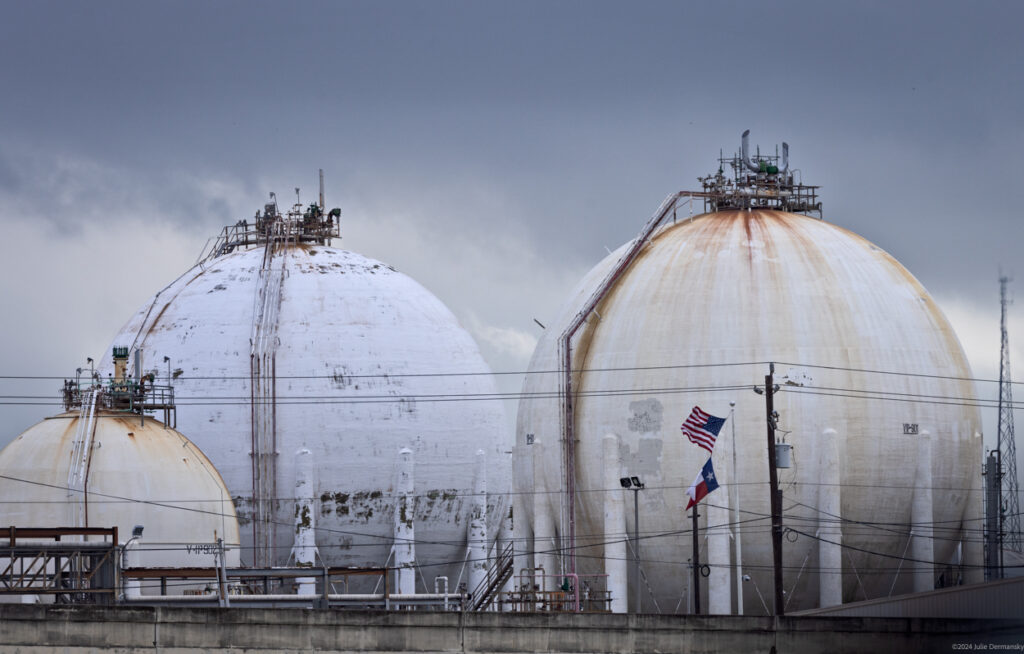

Roughly 200 plants, dotted across the country but heavily clustered along the Gulf Coast, are covered by the new rules. Those plants primarily make chemicals and “polymers and resins,” or plastics — and they release dangerous chemicals into the air in the process.

The new rules, years in the making, update Clean Air Act standards on a half dozen pollutants from those plants, including the highly carcinogenic EtO and benzene, chloroprene (used to make the neoprene that’s found in wetsuits), vinyl chloride (which was notoriously burnt off in the East Palestine, Ohio, train derailment), a vinyl chloride precursor known as ethylene dichloride, and 1,3 butadiene (used to make synthetic rubber).

The EPA has said its rule “will provide critical health protections to hundreds of thousands of people living near chemical plants.”

The environmental groups’ lawsuit comes shortly after Denka Performance Elastomers asked the D.C. Circuit to block the rules from going into effect in May. Denka, a Japanese company, alleged that the EPA allowed too little time for the company to slash chloroprene emissions from its LaPlace, Louisiana, operations, giving the company just 90 days, while other chemical manufacturers would be allowed two years to curb their emissions.

Denka’s claims have drawn public support from the state’s governor, Jeff Landry, and Louisiana attorney general Liz Murrill, who also filed a D.C. Circuit challenge, citing concerns that the Denka plant could be shut down.

Back in April, DeSmog first reported on concerns that loopholes in the rules, combined with plans from companies like Koch Industries to expand their operations, could mean Louisiana’s Cancer Alley won’t see a decrease in total toxic air pollution.

A July 16, E&E News investigation found that tightened EPA regulations governing hazardous air pollution from oil refineries – a similar set of rules to the ones covering chemical and plastics plants – successfully tamped down dangerous emissions from most of the 130 refineries reviewed. Dozens of other refineries, however – mostly located in communities of color – saw emissions rise. Troy Abel, a Western Washington University professor of environmental policy, faulted “less stringent rules enforcement in some states versus others.”

This week’s legal challenge to the rules for plastics and chemical plants doesn’t specify what criticisms the groups intend to raise before the court.

But attorneys for environmental groups behind the new lawsuit filed July 16 said that while EPA’s rule marks an improvement in many ways, it also contains some dangerous flaws.

“The basic structure of the rule is good, we just don’t think it runs far enough,” Abel Russ, a senior attorney for the Environmental Integrity Project, told DeSmog.

That, Russ said, is in part because the rules were built based on emissions estimates provided by industry — despite evidence that emissions are actually at least an order of magnitude higher than industry claims.

“EPA takes emissions estimates, which generally come from industry reports, and they assume that they’re accurate,” Russ said. The EPA then baked those estimates into its risk calculations, he added.

The problem is, when the EPA has checked industry estimates against actual fenceline data, Russ said, real-world emissions tend to be much higher than the estimates predict.

That, incidentally, tracks with new peer-reviewed research, published in the journal Environmental Science and Technology a few months after EPA’s rule was finalized. Researchers from Johns Hopkins University found that in over a dozen census tracts in Louisiana, median measured EtO concentrations were 22.7 parts per trillion (ppt). EPA’s model estimated levels would be 2.5 parts per trillion.

In other words, EPA’s estimates on EtO missed nearly 90 percent of the EtO that the researchers measured in the air.

In response to similar concerns raised during the public comment process, the EPA wrote that it “recognized” that “facility-wide emissions estimates” were generally not ”subjected to the same level of engineering review” as other estimates but that those numbers nonetheless “remain important for providing context as long as their uncertainty is taken into account in the process.”

“Even though EPA knows the estimates they’re using are wrong, they’re calculating risks and making a determination about the need to tighten standards further based on their risk estimates, which are all based on numbers that they concede are wrong,” Russ said.

Taking EPA’s numbers at face value, the rules still leave millions of people exposed to dangerous pollution from the plants.

EPA’s risk assessment shows over 6 million people will face elevated cancer risks even after EPA’s new rule goes into effect, Russ, who has a background in toxicology and is also director of the Center for Applied Environmental Science, pointed out — and that number is based on what the environmental groups say are lowball risk figures.

“I’m concerned that EPA has left a lot of people in harm’s way,” he told DeSmog.

Nonetheless, the fact that EPA acted on EtO and other chemicals still marks “an important step,” he told DeSmog.

The risks associated with EtO have proven divisive.

In Louisiana’s Cancer Alley, for example, many community groups praised the EPA as it announced it would act on EtO.

EPA administrator Michael Regan arrived in person to announce the new rules. On April 9th, flanked by a couple of longtime Louisiana Cancer Alley community leaders, during a small invitation-only celebration for the unveiling of the new rule, Regan said the agency’s recently finalized rule had been calculated to deliver the best possible outcome to frontline communities and that the rule would deliver the best possible potential outcome.

“We’re slashing EtO and chloroprene pollution by an astounding 80 percent, reducing elevated cancer risk for those living near these communities by 96 percent,” Regan said, adding that the rule will lead to the elimination of more than 6,000 tons of toxic air pollution.

But as the specifics have become clear, disappointment has grown. Concerned Citizens of St. John and Rise St. James Louisiana are among the plaintiffs now challenging EPA’s rule.

Concerns over the shortcomings in the rules have split the residents of St. John the Baptist who are concerned over the toxic air pollution, with some continuing to believe the EPA rules can meaningfully reduce pollution while others now see the rules as having too little impact.

Meanwhile, inside the D.C. Beltway, far-right politicos have raised very different concerns over EPA’s EtO rule-making.

Republican Louisiana Rep. Clay Higgins took aim at EPA Administrator Regan over the new toxic chemical rule, posting a photo of Regan on social media platform X. “This EPA criminal should be arrested the next time he sets foot in Louisiana. Charge his ass with extortion,” Higgins wrote under the photo on April 8. “Send that arrogant prick to Angola for a few decades.”

In response, Sen. Ed Markey (D) of Massachusetts slammed Higgins’ post, calling it a “racist dog whistle.”

“The only crime that’s been committed is the decades of negligence by fossil fuel and petrochemical companies,” Sen. Markey added.

The new litigation, filed in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, falls under the same Supreme Court that recently issued the Loper Bright decision, which tossed aside Chevron deference, a legal doctrine that historically gave administrative agencies like the EPA significant leeway over federal rules.

“Loper Bright changes things a little bit. We don’t know what the new level of deference is going to be,” Russ told DeSmog. “It’s a little bit disconcerting what we see coming from the Supreme Court.”

“But there are a lot of cases I’ve worked on over the years where we’ve challenged agency action and we don’t necessarily like the fact that they get deference. We want the court to look critically at what EPA did,” he added. “So maybe there’s a silver lining here.”

At the end of the day, much of the dispute comes down to how seriously the EPA should take discrepancies between industry estimates and real-world emissions levels.

“They don’t think it’s significant,” Russ said. “We disagree.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts