The UK is heading to the polls on July 4. Although it doesn’t get enough attention, the two major parties — the Conservatives and Labour — have chosen climate change and, in particular, fossil fuel production in the North Sea as a clear political dividing line for the electorate.

As polling day draws closer, and election fervour takes hold, we will see the forces of British climate obstruction in full effect. Influential individuals, organisations and media outlets that seek to block, dilute, delay, or even reverse climate policies will attempt to widen that political dividing line with a mixture of claims to be defending individual freedoms, putting growth first, being ‘climate realists’, or by displacing concerns about the UK’s responsibility to act on climate change through ‘whataboutism’.

The Conservative government, under Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, has pushed ahead with issuing hundreds of new oil and gas licences in the North Sea. The government was due to further reform the licensing regime so permits are handed out on an annual basis, all under the auspices of ‘energy security’, but the election has halted the bill’s progress through Parliament. Future licences are expected to yield just three weeks’ worth of gas per year.

Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Party, however, announced that it will end new licensing for oil and gas in the North Sea, with the very large caveat of honouring those already approved. But even this announcement ignited fierce resistance from the media, trade unions, Labour’s political opponents and some figures it deemed allies. The plan was labelled as “Thatcher on steroids”, “naive”, and risked “creating a cliff-edge” for industry and investment in and around the North Sea. In response to the vitriol, Starmer conceded that fossil fuels will continue to be used in the UK “for many, many years”.

This episode provides a useful insight into how climate obstructionism operates in the UK. In a new publication for the Climate Social Science Network (CSSN) based at Brown University, alongside Dr Ruth McKie and Dr James Painter, we identified three major channels through which obstructionism operates in Britain and the network of organisations that sustain it.

Financial Power

The first is the material. This speaks to the financial and structural power of the fossil fuel industry that allows it to use threats of capital flight and job losses to curry favourable policy conditions and fend off tax hikes that would dent profitability. It also speaks to party donations, where fossil fuel firms, or those that benefit from their expansion, provide funds to individual politicians or the wider party for access and a say over policy.

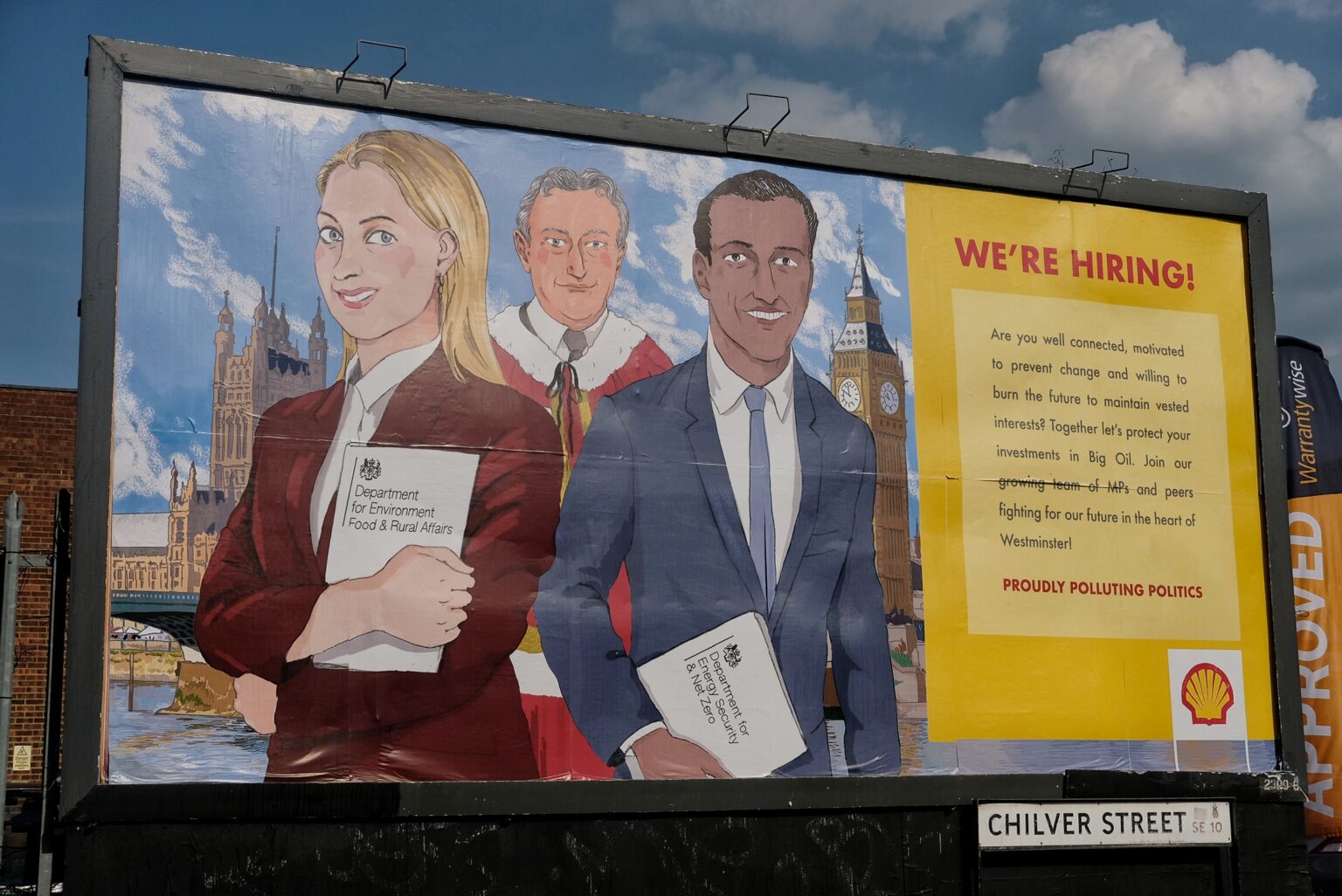

Since 2019, the Conservatives have received £8.4 million in donations from big polluters and those with direct links to fossil fuel production. The current Energy Security and Net Zero Secretary, Claire Coutinho, accepted a £2,000 donation in January 2024 from Lord Michael Hintze, a funder of the UK’s leading climate science denial group, the Global Warming Policy Foundation. Labour too have taken money from big polluters, most notably Drax, whose North Yorkshire power plant is the UK’s single largest source of emissions.

Alongside the material sits the institutional. The policy making process in the UK provides a multitude of opportunities for actors to shape policy, all within the bounds of proper procedure and due process. All Party Parliamentary Groups (APPGs), informal groups of politicians organised around key themes or policy issues, have provided an effective fora for obstructionist actors to garner access and shape policy. The rules governing APPGs often inhibit public scrutiny. Trade associations, and the companies they represent, can be omitted from official parliamentary transparency logs as only benefits in kind above £1,500 a year must be declared — a threshold many industry bodies claim not to meet.

Revolving doors between industry and government are another institutional means through which fossil fuel interests can determine policy. An investigation by The Ferret found that since 2011, 127 former oil and gas employees have gone into top government roles and been appointed to ministerial advisory boards. At least a dozen of these individuals were given roles in the North Sea Transition Authority, the organisation tasked with governing oil and gas production, as well as within departments responsible for writing energy and climate policy. Shutting this revolving door, or even just slowing it down through ‘cool-off’ periods, would go some way in curtailing obstructionism.

Climate Delay

The final, and perhaps most pronounced, thread of climate obstructionism in the UK is discursive, primarily promoted through the media. The right-leaning media in the UK, such as the Daily Telegraph and Daily Mail, have persistently opposed climate policy and action. This opposition used to be grounded in outright denial, where the integrity of climate science was disputed and denigrated. Now, though, a more pernicious form of discursive obstructionism is prevalent; that of climate delay.

Countless op-eds and articles have been published that acknowledge climate change but dispute the necessity of addressing it, the cost of implementing climate policy (both economically and in terms of national security), and the efficacy of green technologies such as wind turbines, electric vehicles (EVs) and heat pumps. These interventions, which are sometimes made by individuals with direct links to sceptic organisations or else use their framing, often push blatant untruths to the public, such as renewable energy pushing up household energy bills or solar panels jeopardising British farming. The media continues to both demonise climate activists and undermine public support for key climate policies.

In this election, watch out for climate obstructionism. While institutional channels may be curtailed due to purdah, others will pick up the slack. With all parties now firmly on an election footing, donations will become a crucial resource for knocking doors and getting out the vote in marginal seats. The sources of these donations, and the interests behind them, will bear the thumbprint of the fossil fuel industry. The media will increase its scrutiny of manifesto pledges and publish a litany of analyses. It is highly likely that Labour’s climate policy will be painted as a threat to national security, an insurmountable cost to the public purse, and reflecting the demands of both Vladimir Putin and Just Stop Oil simultaneously. The foundation of this framing has already been set.

What is less clear, though, is what comes after July 4. With a change of government comes a reconfiguration of interests and, for the winners, concessions will be made to those actors and constituencies that helped get them past the post. For the losing party, most likely to be the Conservatives, there may be an ideological reorientation that ends the cross-party consensus on tackling climate breakdown, making them the party of climate obstructionism that challenges the necessity of net zero and fights for more oil and gas.

This election might be the one that ends 14 years of Conservative rule, but it’s not likely to be the one to end climate obstructionism in the UK.

Freddie Daley is a Research Associate at the Centre for Global Political Economy at the University of Sussex.

Peter Newell is a Professor of International Relations at the University of Sussex.

They are the authors of a chapter in Climate Obstructionism across Europe, a new collection of essays analysing the organisations, politicians, think tanks and media outlets seeking to delay, derail and denigrate climate policy, produced by the Climate Social Science Network.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts