Fossil fuel interests spent millions of dollars in an effort to influence Colorado’s recent legislative session, a DeSmog analysis shows — and environmental advocates say the campaign helped to scuttle a raft of clean air bills.

Protect Colorado, a group that received more than $4 million from Chevron, Occidental, and other oil and gas interests, spent heavily to support pro-industry ballot initiatives before and during the session — a critical form of political leverage. Those efforts were aided by an extensive PR campaign spearheaded by the American Petroleum Institute (API), an industry group that spent an additional $3 million on lobbying, media buys, and digital ads from February through May, according to public financial disclosures. API lists Colorado’s three biggest oil and gas companies — Chevron, Civitas Resources, and Occidental — among its members.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts

In May, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis, a Democrat, announced that his administration had brokered a deal between those three companies, a handful of environmental groups, and regulatory agencies. The compromise was hailed as a “grand bargain” that balanced industry priorities with the need for environmental reforms in a state with mounting air pollution woes.

But several activists directly involved with the negotiations expressed frustration to DeSmog, saying that the industry’s intensive campaign — combined with the threat of a gubernatorial veto — resulted in weaker new protections than legislators had seemed poised to approve. Democrats control Colorado’s House and Senate by a broad margin.

“The ads were really detrimental to the narrative in our state,” said Margaret Kran-Annexstein, director of the Colorado chapter of the Sierra Club and one of the environmental leaders who brokered the deal. “I think that with more bravery from the governor, we may have had a different outcome.”

Kran-Annexstein and other advocates said the compromise bills were still a win for the environment, despite industry interference.

But in a text message to subscribers, Energy Citizens, the API-funded astroturfing group that took a central role in the ad campaign, claimed its own win.

“It’s clear that Energy Citizens made a HUGE difference!” it wrote. “Fortunately, the extreme anti-energy bills did not pass!”

Oil and Gas Sets the Stage

The fossil fuel incursion into the 2024 legislative session began months in advance.

In the spring of 2023, Safe & Healthy Colorado, a coalition of state environmental groups, launched a statewide ballot initiative to phase out new oil and gas permits by 2030. That effort failed to get enough signatures to proceed. But it appears to have inspired fossil fuel interests to get their own priorities on the ballot — a direct appeal to voters that was much better funded, and ultimately more successful.

Several similarly-worded measures sought to bar state and local governments — in the words of one proposal — from “discriminating against” certain forms of energy use.

The idea was to prevent rules that would restrict oil and gas extraction for health, environmental, or other reasons.

Representatives from West Group, a law and policy firm, proposed the first of these “energy choice” ballot measures in August. In November, Chevron and Occidental each gave over $1.4 million to Protect Colorado, an oil and gas industry advocacy group supporting the measures. That month, Protect Colorado spent over $2.2 million on consulting and signature collection for the effort, according to public documents. In the months that followed, Protect Colorado spent $1.2 million more on signature collection, plus more than $50,000 in legal fees to West Group.

Those efforts put environmental groups at an immediate strategic disadvantage heading into 2024’s legislative session.

The industry-backed initiatives “would have undermined building codes, they would have undermined clean heat requirements, they would have limited our ability to regulate utilities and made the adoption of electric vehicles much more challenging,” Sierra Club’s Kran-Annexstein said. “So we really saw them as existential threats to the state of climate progress in Colorado.”

“The threat of the ballot measures was the true sword of Damocles hanging over our heads,” said Jessica Goad, vice president of programs at Conservation Colorado, an environmental nonprofit. “Industry has unlimited funding to try to influence things on the ballot. They could have passed these measures.”

Soon after the 2024 legislative session kicked off in January, lawmakers introduced a suite of proposals intended to rein in ozone pollution from oil and gas activity, the very sort of bills the industry’s ballot measures seemed designed to block.

Ground-level ozone — the key component in smog — results when certain pollutants react with sunlight. In Colorado, emissions from fossil fuel extraction and processing are a major contributor. Ozone pollution is linked to shortness of breath, asthma attacks, and heart damage. Long-term exposure can lead to a range of serious health complications, according to the American Lung Association.

Communities along Colorado’s Front Range suffer from a “severe” ozone problem, according to a 2022 assessment by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, and the state has repeatedly failed to stay below federally mandated ozone thresholds in recent years. Between 2021 and 2023, Colorado health officials issued more than 140 “ozone action day” alerts, warnings issued to residents about high exposure levels.

Three of this session’s clean air bills came directly out of 2023’s Legislative Interim Committee on Ozone Air Quality, an effort by lawmakers to understand the root causes of ozone pollution and develop policy solutions. HB 1330 would have restricted new permits for oil and gas operators whose emissions contribute to the continued violation of federal air standards, while also blocking exploration in areas that disproportionately bear the brunt of the region’s ozone pollution. SB 165 would have mandated new rules for limiting air pollution from a range of sources, while empowering Colorado’s Air Quality Control Commission to require emission reductions during the peak ozone season. And SB 166 would have increased penalties for repeat violators of air pollution laws.

This legislative package was endorsed in February by a broad coalition of Colorado environmental groups. Two additional bills proposed that month were potentially even more far-reaching, though from the start they were also less likely to pass. HB 1339 would have prohibited greenhouse gas emission increases from the industrial sector, established a cap-and-trade program for the state, and mandated environmental justice representation on the state’s Air Quality board. SB 159, which mirrored 2023’s failed ballot measure, called for a phaseout of all new oil and gas permits by 2030, while also mandating much stricter requirements around the cleanup of oil and gas wells.

But fossil fuel interests had readied a well-funded counterpunch.

A $3 Million Advertising and Influence Campaign

Starting in early March, according to public financial disclosures, API spent heavily to target the legislative initiatives. It paid Main Street Media Group just over $2 million for TV and radio ad buys that started running March 1. According to data compiled by a veteran Democratic strategist and shared with DeSmog, the ads ran on network TV, cable, and FM radio stations between March 4 and May 8 in the Denver and Colorado Springs-Pueblo markets.

API also spent an additional $223,000 on ad production, digital media campaigns, direct mail, signs, banners, billboards, and “tele-town hall” consulting, according to financial disclosures.

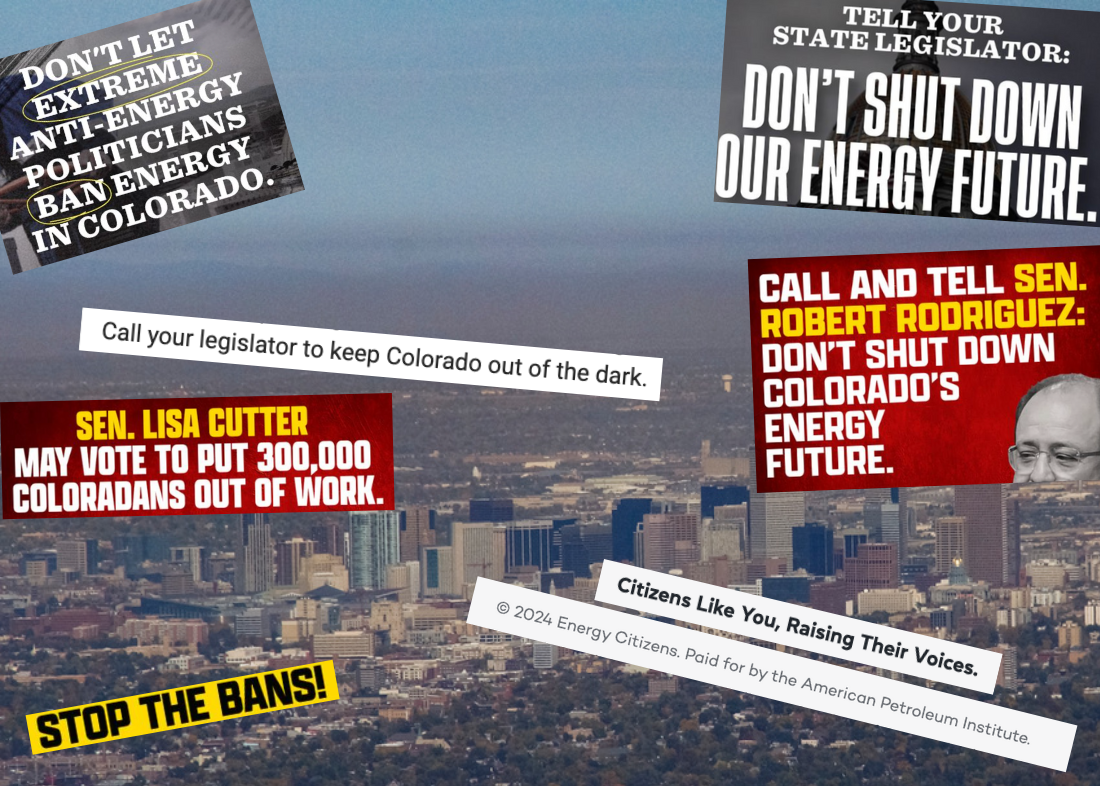

Many of the ads reviewed by DeSmog claimed that lawmakers’ proposals would cause power outages and increase dependence on foreign energy, misleadingly suggesting that they amounted to a de facto ban on oil and gas.

“Colorado politicians are pushing extreme bills that would leave Colorado struggling to keep the lights on, banning reliable energy without a plan to meet growing needs,” one TV ad claimed, directing viewers to a “Stop the Bans” page on Energy Citizens’ website that accused “a few politicians in Denver” of sponsoring “the most extreme anti-energy legislation in state history.”

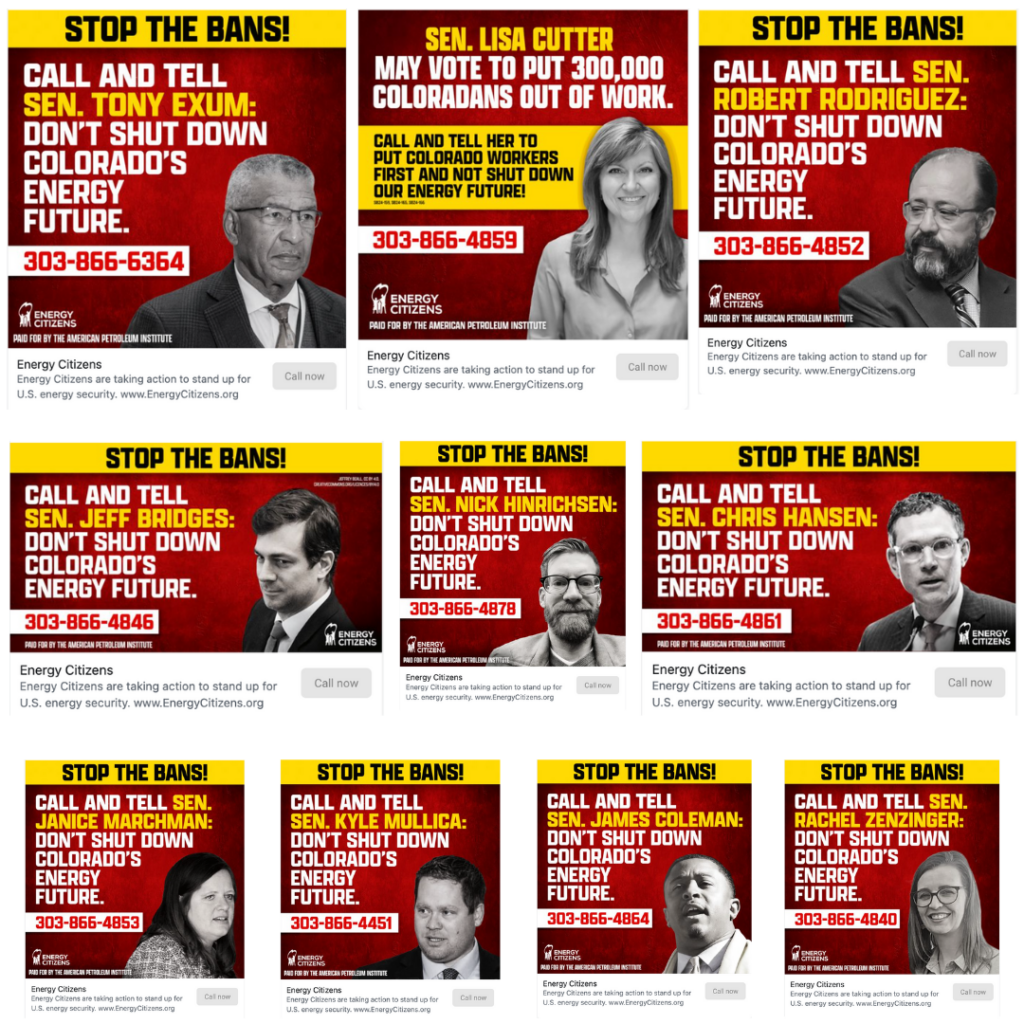

The digital campaign on the Google and Meta advertising ecosystems also promoted the narrative that a handful of radical lawmakers planned to shutter the state’s fossil fuel industry. Ads running on Facebook and YouTube often referenced specific legislators, asking the public to call and demand they “put Colorado workers first and not shut down our energy future.”

At the same time, Protect Colorado continued to fund additional “energy choice” ballot measures between December and March, according to state documents. In response, an environmental coalition filed three new countermeasures that month, including an initiative that sought to enshrine a legal right to a “healthy environment” for state residents.

In April, API spent heavily for a second straight month, paying $780,000 for TV and radio spots and nearly $100,000 on digital ads, social media, and billboards. By then, the bill to phase out new oil and gas operations by 2030 had already been rejected by lawmakers. But API’s campaigns continued to use “stop the bans” language in opposition to the more moderate bills.

“Politicians are pushing for a ban on oil & natural gas development,” claimed one ad that ran in April. “Call your legislator to keep Colorado out of the dark.” API-sponsored ads with similar themes were shown millions of times on Google and Meta platforms in April and May, according to a DeSmog review, weeks after SB 159 had fizzled.

Neither API nor Protect Colorado responded to requests for comment.

“A key part of their strategy was to paint really crucial legislation that would reform production of oil and gas development in the state — truly, just reform it, not phase it out or anything — as a threat to Coloradans, even painting specific lawmakers that supported those bills as extreme,” Kran-Annexstein said. “In reality, it was common-sense protections for communities and a reduction in some of the most polluting projects.”

Ean Thomas Tafoya, Colorado state director of the environmental justice nonprofit GreenLatinos, said the lawmakers who sponsored the clean air legislation were “tough as nails” throughout the process — he didn’t think the ad campaign spooked them. But it was, he said, “a flex on the amount of money that [fossil fuel interests] were willing to spend to win the ballot issues.” That reminder of how much cash the industry was willing to burn acted as an important source of leverage.

“Let’s not just pretend we live in a world where oil and gas ballot initiatives, and the spending of industry, doesn’t impact policy. It does,” Tafoya said. “There’s no ifs, ands, or buts about it.”

At the same time, industry groups and companies — including API, Occidental, and Civitas — mounted an influence campaign on Colorado’s Capitol Hill. According to data from the Colorado Secretary of State’s office, lobbyists working to oppose or amend the clean air bills outnumbered those supporting the measures by more than 2 to 1.

‘I Could See the Will … Dwindling’

Commerce City councilmember Renée M. Chacon, who participated directly in this session’s legislative negotiations as co-founder of the Indigenous-led environmental justice organization Womxn from the Mountain, said the industry’s advertising and influence campaign made clean air legislation a harder sell.

“The fear-mongering starts with the public grassroots on up,” she said. “So when legislators are coming in and hearing this on the news and the radio, and then we’re actually bringing the know-how telling them how it’s going to apply, they already have a stigma or a bias no matter what we technically say.”

About a month before the session ended, she said, “I could see the will kind of dwindling.”

Several advocates felt that environmental advocates weren’t only up against industry money, but also the likelihood of a Polis veto.

“It became clear pretty early on that he was not going to support the three bills that we were prioritizing as the ozone coalition,” Kran-Annexstein said.

Tafoya cited SB 165’s mandatory emissions reductions during the peak ozone season as one policy the governor’s office specifically opposed.

On April 29, the Polis administration announced that it had helped broker a deal. Chevron, Civitas, and Occidental would table their ballot initiatives — the “energy choice” measures they spent millions supporting that turned out to be an important bargaining chip. Environmental groups would stop pursuing their own ballot measures, while legislators would voluntarily kill the clean air legislation they had sponsored. All sides agreed to support the speedy passage of a pair of new bills, which delivered some environmental protections while also appeasing industry.

Together the new laws set emission-reduction targets to help reduce ozone pollution, require the state’s energy commission to appoint two liaisons from disproportionately impacted communities, and impose an additional fee on state oil production that would go toward funding public transit projects and land reclamation.

“In coming together, this diverse group agreed that costly, divisive ballot measures and legislation are not in the interest of the state,” Polis told reporters during a news conference at the Capitol that day. “It’s better to find a way to work together to have an outcome that everybody can live with and move the ball down the field in terms of achieving our goals.”

In an emailed statement, a Chevron spokesperson praised the compromise bills, calling them “a good outcome for Coloradans to provide the energy we need, economy we want, and environment we value.” The compromise, she wrote, “further builds on some of the country’s strongest oil and gas regulations developed in Colorado and enables us to remain focused on safely providing the affordable, reliable, ever-cleaner energy our state needs for heat, power, transportation, and our economy.”

Tafoya believed the original spirit of the session’s clean air bills was preserved, despite concessions at the negotiating table. At one of those early meetings in March, he wrote down 22 priorities. “Twenty of them made it in,” he said.

Others had mixed feelings.

The compromise bills, Kran-Annexstein said, “were not what we wanted to pass. They were not real reforms on permitting and real enforcement requirements coming from the government. But given the political circumstances that we were in, we saw it to be a net positive — we would be able to pass some important legislation and get rid of these ballot measures at a time when climate action is so urgent for all Coloradans.”

Chacon said too many environmental justice provisions in the original bills fell by the wayside in the compromise, citing that as one reason she dropped out of the process early. “It weakened the climate initiatives in Colorado, it weakened the ability to address equity priorities” for disproportionately impacted communities, she said. A provision in HB 1330 that would have restricted oil and gas construction permits in those communities, for instance, did not make the cut.

Chacon is also concerned that green groups so readily agreed to a three-year moratorium on ballot measures related to oil and gas drilling. Chevron, Civitas, and Occidental made the same commitment, but API — and other industry-funded groups — did not.

“Having a cooling-off period for the biggest green organizations in our states that do actually work with BIPOC organizations ended up weakening the climate initiatives that we needed to push, honestly,” Chacon said. “We’re not nearly going to have the lobbyists or the representatives or even the capacity to bring the same type of climate initiatives … because all of those big greens are now stepping down.”

It is unclear how the moratorium will be enforced. Between May 1 and May 10, after the “grand bargain” was finalized but before the bills were signed into law, Occidental donated $1.1 million to Protect Colorado, DeSmog found. This month, Protect Colorado spent $500,000 on TV and digital ads; public documents gave no further insight into the purpose of that spending.

Occidental did not respond to requests for comment.

In an emailed statement, Ally Sullivan, Gov. Polis’s deputy press secretary, said the governor was grateful that stakeholders worked to “put progress above perfect and move Colorado forward,” and called 2024 “a year of historic progress.”

“Hundreds of millions of dollars will now be invested to transition our transportation system away from fossil fuels and new regulations to addressing climate change and protecting Colorado’s clean air,” she wrote.

For its part, API — through its mouthpiece group, Energy Citizens — declared victory. A day after Polis signed the compromise bills into law, Energy Citizens sent out a celebratory text message to supporters.

“A suite of extreme anti-energy legislation officially met its demise in the CO General Assembly,” it wrote, before describing Energy Citizen’s central role in the outcome. “Onward!”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts