Over 160 experts and civil society groups are calling on the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) to remove carnivorous fish farming from its definition of “sustainable aquaculture” ahead of World Ocean Day on 8 June.

As industrial aquaculture expands globally, concerns are mounting among academics, fishing communities, and campaign groups about the environmental and social impacts of farming species like salmon, shrimp, and sea bass – carnivorous fish that are reared on wild-caught fish for feed.

The FAO has advocated for the growth of aquaculture and claims the sector can play a bigger role in feeding the world “sustainably” in the face of climate change and a growing global population – a stance the EU and salmon companies have eagerly echoed. But the signatories of the letter raised a host of concerns with large-scale fed aquaculture, and the hazards that farms can create for local communities around the world that are reliant on wild fishing and tourism.

Academic studies have also critiqued the aquaculture industry’s food security claims as “empirically inaccurate”. One 2020 paper published in Nature stated that high-market value, carnivorous fish species in particular will “remain inaccessible to low-income consumers and the food-insecure”.

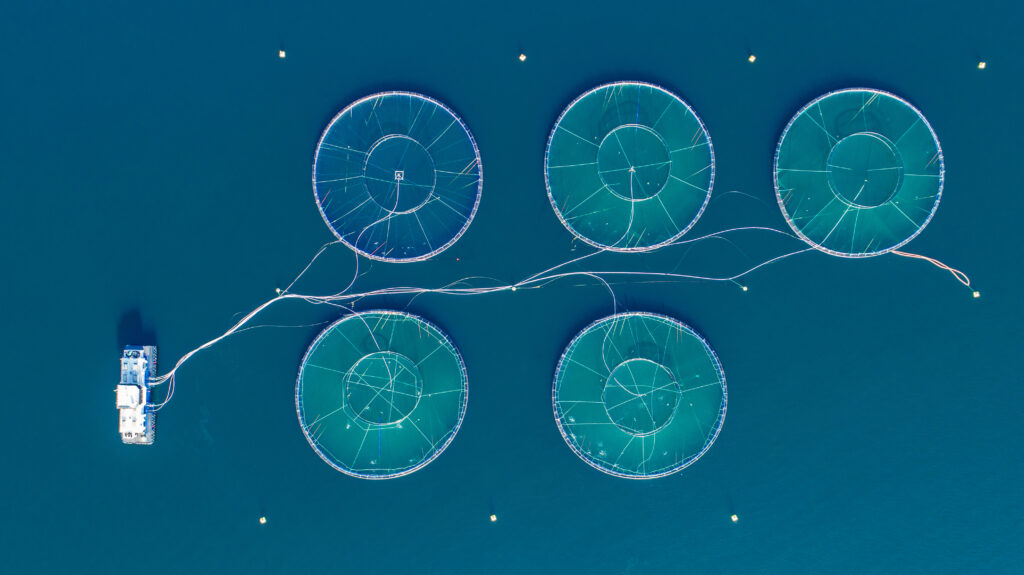

The group’s letter and petition – co-written by the Argentina-based Global Salmon Farming Resistance, Greek nonprofit Katheti, and the U.S. campaign group Don’t Cage Our Oceans – highlights the ecological dangers of industrial-scale, marine open-net pens in particular.

Fish producers use these pens to enclose and farm huge numbers of carnivorous fish – the fastest growing food sector in the world. The fish must eat aquafeed that contains fishmeal and fish oil that is made from wild-caught, nutritious pelagic (oily) fish, like mackerel, anchoveta, and sardines, much of which originates from the Global South. In some parts of the world, this puts industrial fish farmers in direct competition with local communities for nutritious, low-cost protein, which has led to accusations that the industry is re-routing nutrients away from the poor to feed consumers in the Global North.

The letter also takes issue with pollution from fish farms. Their operations pollute the surrounding marine environment with microplastics, antibiotics, and chemicals such as formaldehyde, as contaminated water flows through nets into the open sea. The resulting pollution harms local fishing and tourism in countries including Greece, Chile, Tasmania, Spain, and Scotland.

“There is a dire need to differentiate what is sustainable aquaculture, like seaweed or small scale bivalve farming, versus what is destructive,” Eva Douzinas, co-founder of Katheti and president of the U.S. Rauch Foundation, said in a statement.

“Fish farming of carnivorous species such as salmon, sea bream and sea bass (branzino) is proven to be wholly unsustainable. It is an industry that depletes the world’s wild fish stocks and destroys marine ecosystems, not sustains them.”

‘World’s Fastest Growing Food Industry’

Industrial aquaculture has skyrocketed around the world in the last two decades, increasing from just under 20 million tonnes of aquatic biomass produced in 1991 to more than 120 million tonnes in 2020, according to the FAO.

Aquaculture is a broad umbrella that encompasses everything from lower-impact seaweed, kelp, and bivalve farming, to intensive production of carnivorous fish, some species of which – in the case of salmon – require high volumes of fish oil to stay healthy and grow.

In December 2023, the FAO published a roadmap for meeting the UN Sustainable Development goal number two – “Zero Hunger” – without breaching 1.5 degrees of global warming.

In that report, FAO recommended “at least 75 percent growth in global sustainable aquaculture production compared to 2020 level” – a sharp increase that would see a dramatic rise in the number of wild-caught fish required to feed farmed fish.

But the same oily, pelagic fish targeted by the fishmeal industry can be a community’s only affordable source of protein and critical micronutrients, particularly in West African countries including Senegal and the Gambia.

The vast volumes of fishmeal and fish oil required by carnivorous fish farms make onlookers wary of such a rapid expansion of – and funding for – aquaculture without checks on what types of food are being produced. The EU, for one, has invested 1.4 billion euro into the industry since 2014, according to the EU Court of Auditors, despite the fact that farmed salmon alone – which only makes up 4.5 percent of seafood produced by the global aquaculture industry – now consume 44 percent of the world’s fish oil, according to calculations made by DeSmog (based on a 2022 report published by the FAO and a 2022 study).

“The headlong rush to expand industrial fish farming, a sector which is dominated by large agribusiness corporations, is deeply troubling,” Natasha Hurley, director of campaigns at food and environment campaign group Feedback, said in a statement.

“Our research shows that their feed sourcing practices are negatively impacting food security and robbing communities in the GlobalSouth of key nutrients and sustainable livelihoods.”

The letter to FAO also pointed out harsh environmental impacts from carnivorous fish farming in open-net marine pens. These include an increase in harmful algal blooms, pollution from debris left behind by fish farms, and the buildup of feed and faeces below nets that kill off seagrasses like the endangered Posidonia meadows, which are now recognised as critical carbon sinks.

“The bottom line is that in our current world there is NO farming of carnivorous fin fish which is environmentally sustainable,” the open letter stated.

“We need concrete, enforceable international standards for the remediation of damaged environments and the expansion of genuinely sustainable aquaculture options.”

Learn more about the global aquaculture industry in DeSmog’s Industrial Aquaculture Database, where we document major players’ stances on sustainability, information on fish feed supply chains, and lobbying records.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts