With its unparalleled purchasing power and exacting demands, fast food has long shaped agricultural systems in the United States, Europe, and China. But as major American fast food brands, like KFC, expand into so-called “frontier markets,” taxpayer-funded development banks have made their global expansion possible by underwriting the factory farms that supply them with chicken, a DeSmog investigation has found.

In all, the investigation identified five factory-scale poultry companies in as many countries that have received financial support from the International Finance Corporation (IFC, the private-sector lending arm of the World Bank Group), the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), or both since 2003, and that supply chicken to KFC. A sixth company has benefited from IFC advisory services but has not received financing.

A review of press accounts, financial disclosures, and the companies’ websites shows this support aided these firms’ KFC-linked operations in up to 13 countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe.

In Kazakhstan, both banks helped a Soviet-era poultry factory become a KFC supplier. In 2011, the IFC lent poultry company Ust-Kamenogorsk Poultry (UKPF) invested $2 million in refurbishing housing for chickens, among other projects. In 2016, the EBRD made a $20 million equity investment in the company’s parent, Aitas, to finance the construction of a new facility to raise and process poultry. In 2018, two years after announcing the financing deal, UKPF revealed it had become a supplier to KFC in Kazakhstan. The EBRD sold its stake in the company in 2019.

In South Africa, the IFC helped one KFC supplier bolster its operations across the region. In 2013, the bank loaned Country Bird Holdings $25 million to expand existing operations in South Africa, Botswana, and Zambia. Country Bird supplies KFC in all three countries, as well as Mozambique and Zimbabwe. Three years later, in 2016, Country Bird also became KFC’s sole franchisee in Zambia.

In Jordan, the EBRD’s technical support and a 2015 loan worth up to $21 million helped poultry company Al Jazeera Agricultural Company upgrade its facilities and expand its retail presence. Al Jazeera claims to produce half the country’s restaurant-sold chicken. It includes the local franchisees of KFC and Texas Chicken (known by its original name, Church’s Chicken, in the U.S.) as clients.

With this Global North-financed fast-food expansion comes a host of environmental, social, and health concerns in regions often unprepared to field them.

“It’s so clear that these investments are not consistent with any coherent notion of sustainable development,” Kari Hamerschlag, deputy director for the food and agriculture program at Friends of the Earth US, told DeSmog.

Providing Financial Security for Fast Food Suppliers

Both the IFC and the EBRD are financed primarily by the governments of developed countries for the benefit of developing countries. The IFC was founded in 1956 under the umbrella of the World Bank Group to stimulate developing economies by lending directly to businesses. Founded in 1991, the EBRD was formed to support Eastern Europe’s transition to a market economy. Since then, it has extended its geographic reach to include other regions.

Development banks often finance companies and projects in regions that more risk-averse commercial banks tend to avoid. The idea is to help grow a company’s operations and lower the risk for private sector investors.

Both of these development banks’ investments cover a range of sectors, including manufacturing, education, agribusiness, energy, and tourism. Because large agro-processors, such as poultry companies, can transform bushel upon bushel of local crops into more valuable products, like meat, they make especially attractive clients.

The world’s largest restaurant company, U.S.-based Yum! Brands, owns KFC, and calls the fried chicken powerhouse, which oversees more than 30,000 locations across the globe, a “major growth engine.”

“We must contest the rise of industrial poultry on multiple fronts, for the sake of animal and human labor and the environment that suffers to create a fried chicken leg wrapped in spiced breadcrumbs,”

Kari Hamerschlag, deputy director for the food and agriculture program at Friends of the Earth US

While Yum does not buy chicken or finance producers itself, like most fast food companies, it requires franchisees — the companies that own the restaurants carrying its brand names — to buy chicken from suppliers it designates. Suppliers tend to be large, vertically integrated operations, often complete with facilities for manufacturing chicken feed and processing and packaging chicken meat.

For poultry companies, a Yum contract is one of the most lucrative prizes attainable, as it virtually guarantees sales at quantities few, if any, other buyers can match. But even when Yum restaurants only account for a small portion of a producer’s overall sales, having a relationship with the fast food giant can make a poultry company more appealing to other buyers. As Bruce Layzell, KFC’s then-general manager for new African markets, said in a 2013 interview with the business magazine Africa Outlook, by becoming a KFC supplier, a poultry company can more easily go on to supply other discerning poultry buyers in its region, like hotels and supermarkets.

“Our suppliers are growing with us,” Layzell said. “We do a lot of work with them, bringing them up to standard … It is an upfront investment that might not be paid off in the short term, but the point is to get in early, lay down the right standards, and build a relationship.”

Even before landing a contract, aspiring KFC suppliers benefit from the assistance of Yum’s global staff of supply chain specialists, who offer advice on how to meet the company’s demanding health and safety standards and increase production to land a deal.

| Company | HQ | Region | Brands Served | Countries in which it Serves Brands | Supporting Banks | Type | Year |

| Myronivsky Hliboproduct (MHP) | Ukraine | Europe | KFC, McDonald’s | Ukraine | EBRD, IFC | Loans | 2003 (first) |

| Ust-Kamenogorsk Poultry (UKPF) | Kazakhstan | Central Asia | KFC | Kazakhstan | EBRD, IFC | Loan, Equity | 2011 (first) |

| Country Bird Holdings (CBH) | South Africa | Africa | KFC | Botswana, South Africa, Zambia | IFC | Loan | 2013 |

| Al Jazeera Agricultural Company | Jordan | Middle East | KFC, Texas Chicken | Jordan | EBRD | Loan | 2015 |

| Servolux | Belarus | Europe | KFC | Kazakhstan, Belarus, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, and Azerbaijan | EBRD | Equity | 2018 |

| Sedima | Senegal | Africa | KFC | Senegal | IFC | Advisory |

Fast Food’s Role in Global Agriculture

For a poultry company, a Yum contract and support from a development bank like the IFC can be mutually reinforcing. Formalizing supplier relationships can be a years-long process. Since both Yum and prospective suppliers tend to stay quiet during that time, it can be difficult to determine whether bank support preceded an arrangement with Yum. Nonetheless, bank support has at times coincided with a supplier’s international expansion.

In 2018, for instance, the EBRD purchased an equity stake in Servolux, a Belarussian poultry company, for $11.7 million to finance upgrades to one of the company’s processing facilities. Two years later, Servolux announced a “strategic partnership” with Yum to supply KFC in Belarus, Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Georgia, Armenia, Uzbekistan, Azerbaijan, and Russia. (Yum has since withdrawn from Russia and severed ties with the country.) The EBRD exited the company, along with all companies in Russia and Belarus in December 2022.

For another poultry company in Southern Africa, success, aided by the IFC, precipitated an entry into a new region. Two years after South Africa’s Country Bird Holdings received a $25 million loan from the IFC to expand existing operations in Botswana and Zambia, where it already supplied KFC, the company finalized a purchase of a Nigerian poultry company, Valentine Chickens and quickly integrated that company’s operations into Nigeria’s KFC supply chain.

Of the six companies DeSmog examined, four made arrangements with Yum after the banks announced their assistance.

The suppliers that benefited from bank support have proven essential to Yum’s expansion. Senegal, for instance, banned imports of frozen chicken in 2006, making local production essential to KFC’s entrance into the country. KFC found a producer, a poultry company called Sedima. Though Sedima was not a beneficiary of IFC financing, the bank “helped the company identify areas in which it could increase efficiency and provided strategic advice,” according to a 2018 report. One year later, KFC opened its first outlet in Senegal, with Sedima serving both as the supplier and franchisee.

Francis Owusu, a professor of community and regional planning at Iowa State University, told DeSmog that development finance institutions like the IFC and the EBRD should rethink how they invest in agriculture. The banks “feel it’s hard to work with small farmers because there are so many of them, they don’t have collateral, so it’s much easier to work with bigger institutions,” he said.

While the banks may tout the anticipated social benefits of their clients’ projects, they do not require their clients to see those benefits through, he added.

“They argue these companies are going to create jobs and sell products to people at a reduced price. As with every trickle-down idea, there’s no way to make sure the trickle down actually trickles down.”

While both Yum and McDonald’s regularly attempt to influence agricultural and trade policy in the United States to ensure a more favorable operating environment for their franchisees around the world, a review of lobbying disclosures in the United States found no evidence that either Yum! Brands or McDonald’s lobbied U.S. officials on matters related to the IFC or the EBRD.

But even, apparently, without involving themselves in bank affairs, the fast food industry has long been a factor in the United States’ interactions with foreign countries. U.S. diplomatic officials are regular guests at the opening ceremonies for American fast food restaurants in developing countries. At the opening of the Senegal KFC, for instance, Babacar Ngom, the founder of Sedima, cut the ribbon while flanked by the Senegalese Trade Minister, Aminata Assome Diatta, and Amy Holman, then Deputy Chief of Mission for the U.S. Embassy in Dakar.

Yum! Brands did not return a request for comment.

The Rise of Industrial Poultry in the Developing World

KFC is a natural, if incidental ally to the banks’ development agenda. It was the first international fast food brand to open in Africa, with a restaurant in Johannesburg, South Africa, at the height of apartheid in 1971, and the first to open in China, with a restaurant in Beijing, in 1987. In 1997, KFC’s parent company, PepsiCo, spun off the fried chicken giant along with Taco Bell and Pizza Hut to form a separate company, called Tricon, later renamed Yum! Brands. Financial analysts largely wrote off the new group’s prospects since the United States — its core place of business — was already saturated with fast food.

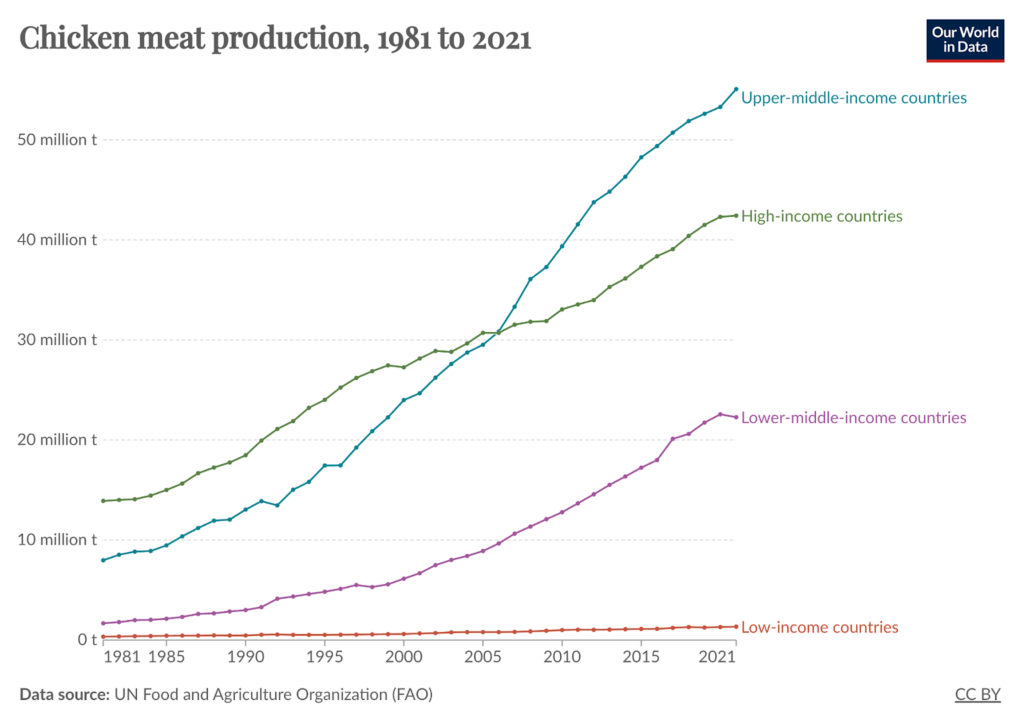

But as household incomes rose in developing countries, Yum found new customers to make up for any losses in its home country. Simultaneously, developing countries, led by Brazil and China, rapidly expanded poultry production.

In a matter of years, Yum went from a risky bet to a Wall Street darling by channeling the global poultry boom into its network of restaurants and satiating a rising appetite for American fast food. As then-CEO David Novak told investors in 2014, the opportunity for expansion in so-called “emerging markets” was “huge.”

“We have three iconic brands and while we have about 60 restaurants per million people in the United States today, we only have two restaurants per million people in the top ten emerging markets, including China and India,” he said. “This is a long runway for international growth and gives us tremendous confidence in our ability to continue our aggressive expansion for many years to come.”

At the time, there were about 40,000 restaurants in 125 countries in the Yum system. Today, the number of restaurants has increased to around 55,000, with developing countries accounting for most of the growth.

As development banks have invested in industrial poultry operations in these countries, finding suitable local suppliers has been easier than ever.

Hamerschlag, with Friends of the Earth US, says the development banks should not be so eager to finance livestock operations in developing countries. Large-scale poultry operations, she says, tend to be inefficient users of food crops, like corn, and the people who eat fast food tend to be food-secure middle and upper-class consumers.

Hamerschlag said the IFC typically claims its agricultural investments will enhance food security in developing countries, but that its investments in fast food suppliers showcase a habit of backing projects that benefit relatively well-off consumers instead of poor people. For that reason, helping to build fast food supply chains isn’t just a failure for the poor, she said. It also means undermining the health of developing countries.

“Through its lending, the IFC is, in effect, facilitating the expansion and growth of these fast food chains, which in turn increases access to what are arguably some of the most unhealthy foods,” she said.

Industrial poultry operations are also a startling contributor to climate change. Though the poultry industry is responsible for less greenhouse gas per unit of meat than beef or dairy, its effect on the climate is substantial. In 2015, broilers, or chickens raised for meat, contributed 368 million metric tons of CO2 equivalent to the atmosphere globally, according to an estimate from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) — almost six percent of agriculture-related emissions. (The figure includes both direct emissions from manure and indirect emissions related to the production of feed and energy use at farms.) As a 2020 Guardian investigation found, the EBRD’s and IFC’s backing of industrial meat and dairy threatens to undermine their recent commitments to fighting climate change.

The global ascent of fast food and meat, more generally, is also one of the major reasons certain diet-related health conditions once unique to the United States and a few other developed countries have been cropping up in developing regions, like Africa, where local health systems are poorly equipped to treat them. From 2000 to 2016, the global obesity rate increased by 4.4 percent, according to an FAO estimate. In West and Southern Africa, the rate was substantially higher.

“As taxpayer-funded entities, IFC and EBRD should require that the recipients of its low-cost financing are avoiding negative environmental and social impacts — not worsening them,” Kelly McNamara, a Friends of the Earth US policy analyst, said. “In the food sector, they should invest in companies that support local farmers to produce healthy, sustainable food for the populations who are most vulnerable to food insecurity — not in companies that are profiting from the expansion of urban fast-food chains.”

Global Industry, Local Problems

Neither the IFC nor any of the listed poultry companies returned requests for comment. In response to questions from DeSmog, an EBRD spokesperson said the bank “only works with companies which have a strong sustainability record and are willing to improve their environmental and social practices as well as significantly reduce their carbon footprint. All our projects are structured to meet EU environmental principles, practices, and standards and to address the causes and consequences of climate change.”

Supporters of large-scale meat and poultry operations say they benefit communities by giving local farmers a market for their crops and by lowering the cost of meat, to the benefit of consumers.

But some projects backed by development banks have drawn serious complaints from their neighbors.

From 2003-2022, the IFC and the EBRD provided Ukrainian poultry giant Myronivsky Hliboproduct (MHP) with more than $600 million in loans — support that helped the company become one of the largest agro-processors in Ukraine. After Yum entered Ukraine in 2012, MHP began supplying the nation’s KFCs through a chicken processing plant near Kyiv. In 2020, that plant began supplying Ukrainian McDonald’s and another plant, further west in Vinnytsia Oblast, joined the fast food company’s list of certified suppliers.

But years of relentless growth, underwritten by the IFC and the EBRD, have taken a toll on Vinnytsia’s environment and its residents. In complaints filed with both banks’ independent review mechanisms, neighbours of the sprawling complex alleged that MHP’s open-air manure pits have polluted the air and water, killing fish and jeopardising the health of local residents. (The resolution process is ongoing. MHP has denied wrongdoing.)

As MHP joined the war effort by supplying food to Ukrainians in their hour of desperation, the IFC and the EBRD stepped up their investments, committing an additional $230 million to refinance bonds and keep the company running.

In response to questions regarding MHP, the EBRD spokesperson said, “MHP is a long-standing client of the Bank, and as such abides by our stringent social and environmental standards. Being the biggest producer of poultry meat products and one of the top edible oil producers in Ukraine makes it a company of vital importance to Ukraine’s and global food security. MHP also plays a crucial social and economic role in Ukraine, which becomes especially important while the country is at war. It should also be noted that MHP’s key poultry production facilities in Ukraine obtained permits to export their products to EU countries and passed the assessment by relevant authorities of compliance with the EU requirements (including animal welfare requirements).”

Ukrainian KFCs, meanwhile, have also remained open for business. As a note posted on the KFC Ukraine website reads, KFC’s suppliers, or “background heroes,” in Ukraine are almost entirely local companies.

The Future of Food Is Chicken

Poultry already holds the top spot among global meat production. Given its myriad cost efficiencies, adaptability across regions, religions, and cultures, and its relatively low emissions per unit of meat when compared to beef or pork, we can only expect chicken to take up an even greater role in humanity’s diet in the future, says Ambarish Karamchedu, lecturer in international development education at King’s College London. But fulfilling a rising global hunger for chicken — raised on factory farms — will inevitably come with a steep cost for biodiversity and for people, he says.

As Karamchedu told DeSmog, the global rise of chicken means developing countries will account for an increasingly large share of the world’s poultry production and consumption, complete with all the pollution and inhumanity the industry entails.

It’s a trend that will likely continue with help from taxpayer-funded development banks such as the IFC and the EBRD, both of which have already pumped billions of dollars into efforts to bring industrial chicken operations into low and middle-income nations.

These taxpayer-supported banks are financing much more than just a fast food chain’s global dominance. But the world does not have to accept that fate, Karamchedu told DesSmog.

“We must contest the rise of industrial poultry on multiple fronts, for the sake of animal and human labor and the environment that suffers to create a fried chicken leg wrapped in spiced breadcrumbs,” he said.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts