While two dozen carbon capture projects are proposed in Louisiana, figuring out exactly where companies plan to inject carbon dioxide underground for storage is a bit of a mystery. That’s because a state law passed in 2021 regulating carbon capture includes a provision allowing companies to claim a wide range of project information — including location — as trade secrets.

The state law mirrors a federal provision that also allows companies to classify the location of their injection site as “proprietary business information” (PBI), which means that, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the most the agency can say without violating PBI status is the parish or county where carbon dioxide will be injected into deep geological formations.

As a result, people concerned about these projects are unable to evaluate their potential for harm until the time-limited public commenting period, which no project in Louisiana has reached yet. Take for example, the case of David Levy, who served on Louisiana’s Oilfield Site Restoration Commission and was concerned about a potential conflict of interest with a carbon capture and storage (CCS) project proposed by ExxonMobil.

Levy has been trying to figure out why the Department of Energy and Natural Resources (DENR) spent more than $900,000 plugging and cleaning up an orphaned wastewater well site on ExxonMobil’s property in Vermilion Parish, about 40 miles southwest of Lafayette, before more polluting and dangerous orphaned well sites. He suspected that Exxon asked the state to clean up the well site in preparation for a carbon capture project in the parish. But Levy was unsure of the exact location where the project’s Class VI injection well — used for long-term storage of carbon dioxide deep underground — would be drilled.

DeSmog filed a public records request for communications between DENR decision-makers and ExxonMobil staff to find clues as to why the state prioritized the saltwater disposal well, called Freshwater City, and if it had anything to do with Exxon’s future plans to store carbon in the parish. The internal emails DeSmog received in response didn’t prove ExxonMobil directed the state to clean up a well abandoned by a smaller, bankrupt oil company on its property. But the records did show locations Exxon considered for their carbon capture project: on state lands, beneath White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area and Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge.

As DeSmog tracked down the location of Exxon’s carbon injection site, the project changed locations and was later put on hold. Still, the proposed project raises red flags about the lack of transparency surrounding CCS permitting in the state, even when projects are proposed for state lands.

Levy was selected to sit on Louisiana’s Oilfield Site Restoration Commission in 2021 because of his knowledge of the oil and gas industry. He owns a company called Petrotechnologies, which designs specialty tools for wells. But he eventually resigned from the commission in December 2022 after coming to believe that the state was selecting orphaned well sites for restoration using state funds based on political favors for well-connected landowners. Emails uncovered by DeSmog’s public record request left Levy with even more questions.

“I don’t know why they want to do this on state lands. It makes no sense either,” he said. “If that place being cleaned up gets tied to CCS in any manner, then it was just a gift to Exxon.”

Freshwater City, the saltwater disposal well plugged by the state, was orphaned in 2015 when its last owner and operator Black Elk Energy went bankrupt. When Hurricane Laura swept through Louisiana in 2020, the storm made a mess of the well site, displacing massive storage tanks and scattering pilings.

Levy says it does not make sense that the state prioritized such a costly site restoration when the well did not appear to be as much of a public health or climate threat as orphaned well sites actively leaking methane. “They spent a very small amount plugging that well,” Levy said. “All the work was to get the tanks within Exxon’s property. So that was the cost. Not the well, which makes it even more bizarre.”

In July 2021, the state sought reimbursement from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) for disposing of the tanks and plugging the well in the wake of Hurricane Laura. Ultimately, FEMA did not agree to reimburse the state for cleaning up the site.

Still, the state paid a company named Gulf Inland Contractors to clean up the site, which the firm completed in April 2022. Before Black Elk, Freshwater City had four previous owners. Louisiana collects fees on oil and gas production to fund its program of plugging wells left behind by oil and gas companies that go belly up. The state has the authority to sue previous owners of orphaned wells to recoup the cost of plugging and abandoning them when the costs exceed $250,000.

Yet, in the case of Freshwater City, the state failed to do so, despite the bill draining nearly $1 million from the orphaned well fund, which typically pulls in just $15 million to $16 million a year.

Storing Carbon on State Land

Less than two weeks after the well was plugged, ExxonMobil’s Joe Coletti confirmed via email that the company had received a signed Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA) from DENR’s attorney, Blake Canfield, regarding a carbon capture project that ExxonMobil could build about 10 miles away from the orphaned wastewater site. The oil giant wanted to take CO2 captured from the largest polluter of greenhouse gases in the state — the CF Industries ammonia manufacturing facility in Donaldsonville, Louisiana — and transport it via pipeline to be stored in state-owned lands in Vermilion Parish.

DENR’s spokesman Patrick Courreges said it is not unusual for the agency’s attorney to sign an NDA with a company when it relates to representing the state’s mineral rights as a landowner. “It can be a protection private companies ask for to ensure their negotiation positions aren’t shared with potential competitors,” he said.

While the company has been hush-hush about where the carbon would be injected, an email from Colleti to DENR staff on May 9, 2022 included a draft operating agreement to store CO2 in deep geological formations beneath White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area and Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge. Exxon proposed that the company would pay $75 per acre to the state for the first two years and $50 per acre after that to inject CO2. The project could inject up to 10 million metric tons of carbon dioxide per year into the state-owned lands. Louisiana’s Mineral and Energy Board voted to move forward with negotiations with the company on May 11, 2022.

But when DeSmog recently asked DENR about the project, the state said the proposed location had changed. To where, the state couldn’t say.

“That one gets a little tricky — our Injection and Mining folks have a Class VI application from ExxonMobil in so they know the proposed site location, but we can’t put it out there yet because the state law that enabled our rules also included the provision that means we have to abide by the federal definitions of trade secrets/business confidentiality on these,” Courreges wrote in an email. But the location of Class V wells, which are being used to test injection pressures for CO2 storage, are not considered trade secrets, nor are the locations of proposed oil and gas wells.

The EPA’s Region 6 Press Officer, Joe Robledo, confirmed that the EPA — which regulates the storage of carbon dioxide in every state but Louisiana, North Dakota, and Wyoming — doesn’t release the exact location of Class VI wells before the public commenting period either. “The highest level of site resolution we can provide without violating [proprietary business information] status is at the Parish level,” Robledo wrote in an email. “At this time, we are unable to release additional location details.”

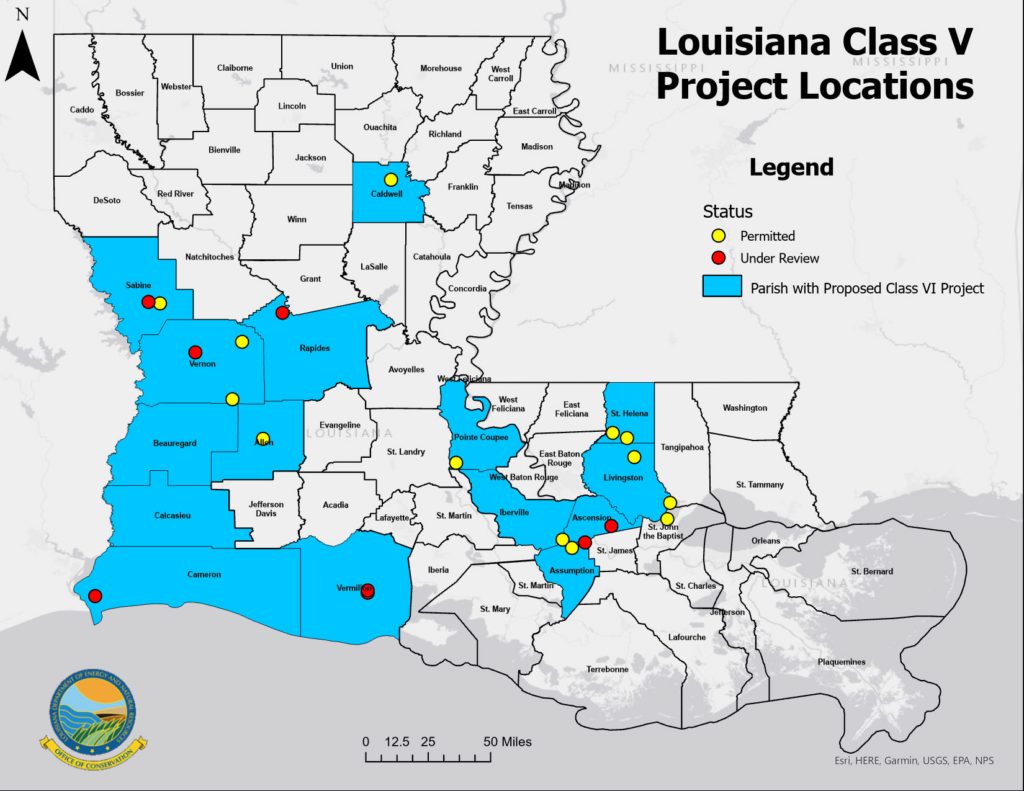

After DeSmog sent questions to DENR about the location of Exxon’s Class VI and Class V wells, the agency published a map of Class V well project locations in Louisiana. These approximate well locations are near where companies plan to inject CO2, as companies will want to test near the final project location.

The state never notified nearby landowners or the public that Exxon was thinking about injecting carbon on state-owned land. Why the company would want to pay to build the CCS project on public land when it owns 125,000 acres in the parish is unclear. One explanation could be that it has to do with Exxon limiting their liability, said Jane Patton, the U.S. Fossil Economy Campaign Manager for the Center for International Environmental Law.

“It is really troubling to me that Exxon, a very large landowner in Louisiana, is trying to use state-owned, protected lands for the injection of CO2,” Patton said. “The public wasn’t the one who profited off the emissions of the CO2 to begin with. So then to try to put the dangerous accumulated pollution in public land after you’ve made an awful lot of money on it, that just seems like foisting all of the bad and none of the good on the public.”

Colleti, who directs Exxon’s Gulf Coast carbon capture ventures, did not respond to questions about why the company wanted to inject CO2 into public land, when it owns land nearby. Since May 2022, the company has not taken any further steps to finalize an agreement with the state for pore space under White Lake Wetlands Conservation Area and Rockefeller Wildlife Refuge. On March 1, Exxon clawed back permit applications for two Class V test wells in Vermilion Parish, telling regulators that the company was reviewing its portfolio after acquiring Denbury, a CCS firm specializing in enhanced oil recovery, last November.

Vermilion Parish is no stranger to oil and gas activity. There are more than 130 well bore holes within five miles of where Exxon planned to drill its two test wells in the parish, said Scott Eustis, Healthy Gulf’s Community Science Director. Each of those holes into the earth could have become avenues for CO2 to escape the geological formation where Exxon wanted to trap the CO2 underground, he said.

Without information about where CO2 injection wells will be located, Eustis said it’s not possible to notify local landowners of the potential risks to their drinking water or assess if there are pathways for leaks, such as underground faults. In areas with underground salt domes, like Vermilion Parish, CO2 leakage and pressure can extend up to 12 miles away from the injection site, according to research by the University of Texas at Austin. A new report commissioned by the nonprofit Environmental Integrity Project warns of the risks of proposing carbon disposal wells in areas dense with abandoned oil and gas wells.

“Class VI applicants cannot keep the locations of the underground plume secret, and also have a comment period,” Eustis said. He questioned how his organization could warn the public about the potential safety hazards of pollution in such a short time frame. Most projects in the state only require a 30-day commenting period. “The risks extend far from the injection site, and can affect hundreds to thousands of landowners, although we hope that will be unlikely,” he said.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts