This story is the first part of a DeSmog series on carbon capture in Europe and was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s flagship plan to slash the country’s carbon emissions is a public relations gift for an industry accustomed to being cast as a climate villain.

Touring oil and gas facilities in Scotland last summer, Sunak praised the “vital” role the sector would play in delivering his government’s pledge to siphon millions of tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) pollution from planned new power plants and industrial sites — and bury the planet-heating gas under the North Sea.

Oil majors Shell, ExxonMobil, BP and others are vying for a promised £20 billion in subsidies to kick-start these carbon capture and storage (CCS) projects. Now, ministers and fossil fuel executives are united in portraying such companies as gatekeepers to the “clean” technologies of the future.

However, documents unearthed by DeSmog show the industry has spent two decades studying how carbon capture and storage technologies could be harnessed to recover billions of additional barrels of North Sea oil — not just for storing carbon dioxide (CO2).

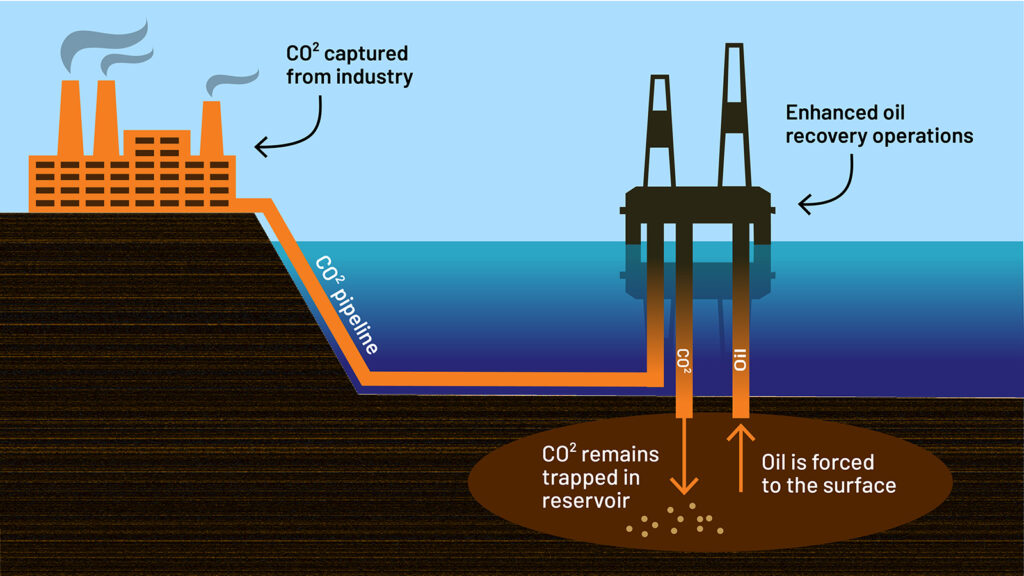

The research focuses on a long-established technique known as “enhanced oil recovery” (EOR) — in which drillers pump CO2 into already developed fields to force remaining trapped crude to rise to the surface, potentially extending a deposit’s lifespan by decades. Pioneered by West Texas oilmen in the early 1970s, the approach has mostly been deployed onshore in the United States and Canada, and more recently in China, throughout the Middle East, and off the Brazilian coast.

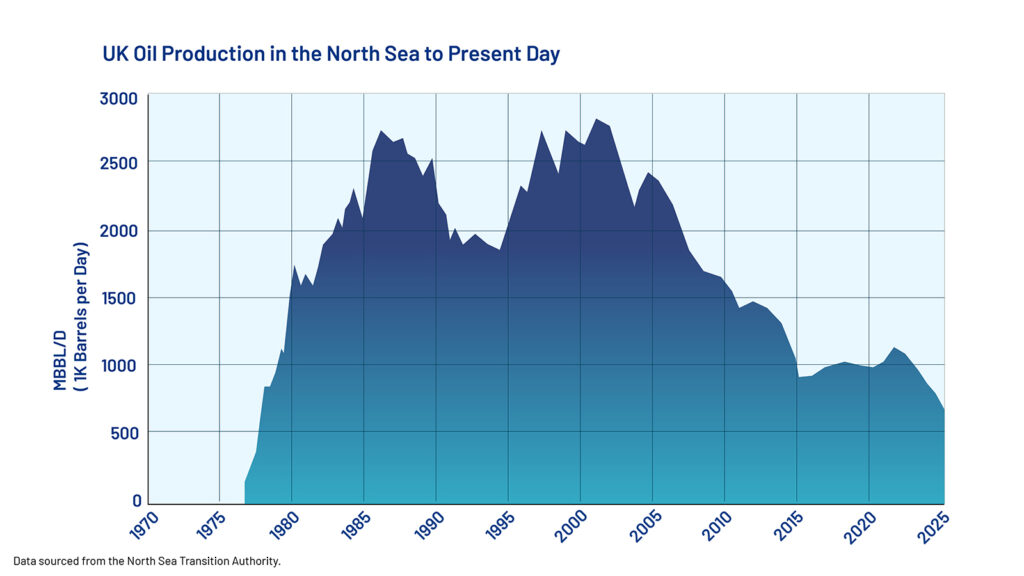

With North Sea oil output in steep decline, enhanced oil recovery could squeeze out an additional three to six billion barrels of oil, the studies reviewed by DeSmog suggest — a significant reprieve for an industry that has pumped about 47 billion barrels since production began in the mid-1970s.

“[Enhanced oil recovery] has the greatest potential for improving North Sea production,” stated a report published in June 2015 by Scottish Carbon Capture and Storage, a research partnership comprised of four universities, whose study was funded by the Scottish government, Shell and several other companies.

“The prize of additional oil is similar, between 3,000 million [three billion] and 6,000 million [six billion] barrels across UK and Norway,” the report found. “That is equivalent to 2 or three super giant oilfields.”

‘Fundamentally at Odds’

With time running out to deploy enhanced oil recovery before the industry begins decommissioning redundant drilling platforms, climate advocates fear the planned new carbon capture projects will serve primarily to prolong business as usual. Prime Minister Sunak’s moves have sharpened those worries.

Even as Sunak backed carbon capture, he took the seemingly contradictory step of unveiling a plan to authorise more than 100 new oil and gas drilling licences during his Scottish visit — pledging to “max out” opportunities in the North Sea.

The decision drew fierce criticism from climate campaign groups and scientists, who warned that expanding oil production would cancel out the impact of the government’s carbon capture plans many times over. Regulators have since approved drilling at the UK’s largest untapped reserves in the Rosebank field, which holds an estimated 300 million barrels of oil.

Shell, Exxon, Norwegian state oil company Equinor, industry associations, and government officials issued various statements to DeSmog saying they had no plans to use enhanced oil recovery to boost oil and gas output in the North Sea.

However, given the oil industry’s long history of misleading the public over what it knew about climate change, and attacking climate science, climate advocates are wary. The fear is that companies will make good on their years of research by using enhanced oil recovery to grab the last drops of oil and gas — then abandon pledges to spend decades, and many billions of dollars, injecting hundreds of millions of tonnes of CO2 into the exhausted wells.

“While no plans for offshore [enhanced oil recovery] in the North Sea have been publicly announced yet, there’s reason to be concerned about the number of offshore CCS projects in the region that plan to use depleted oil or gas wells for carbon storage,” said Lindsay Fendt, a researcher with the Center for International Environmental Law, and co-author of a report on the risks of offshore carbon storage published last November.

“Extracting oil is fundamentally at odds with the climate action these CCS projects claim to advance. But if companies can make more money selling the oil in these depleted wells than they can just storing industrial carbon waste in them, it’s hard to believe that they won’t try,” she said.

Industry is aware that such concerns could undermine public support for carbon capture, according to a memo written by officials at Ofgem, the UK gas and electricity regulator, dated October 26, 2022, and obtained by DeSmog via a Freedom of Information request.

The heavily redacted memo featured the header, “Mainstreaming of CCS (how to get the public on board),” which summarised themes that had emerged during a conference staged by the Carbon Capture and Storage Association, an industry group.

Underneath the header, a bullet read: “CCS cannot be seen as a way to continue business as usual (in particular in relation to concerns over enhanced oil recovery).”

Long History of Research

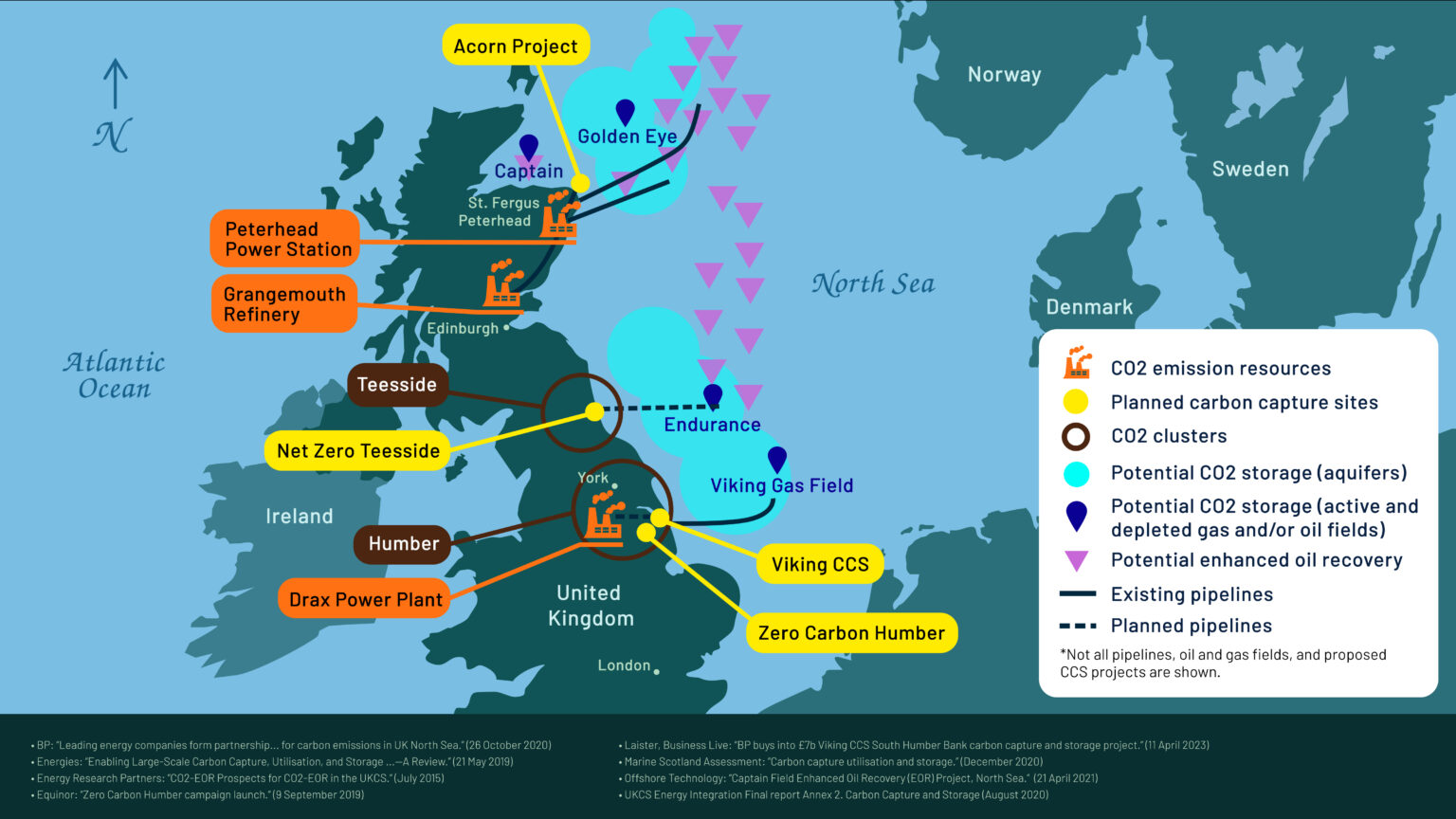

The UK’s carbon capture strategy rests on four planned capture clusters in Scotland, the industrialised Humber and Teesside regions on England’s east coast, and a site near Liverpool. These projects form the main pillars of the government’s plan to boost carbon capture capacity from zero today to 20 million tonnes by 2030 — one of the most ambitious roll-outs of the technology anywhere in the world.

Sunak used his Scottish visit to back a long-planned project northeast of the oil hub of Aberdeen, known as Acorn, which is owned by Shell and Harbour Energy. Acorn aims to pipe up to five million tons of CO2 to be captured from the St Fergus gas terminal each year for injection into partially depleted oil and gas fields more than 100 kilometres offshore.

Sunak also greenlit a project known as Viking, which is designed to transport and store CO2 emissions captured from the heavily polluting Humber region, home to the Drax biomass-burning power complex. A joint venture between Harbour Energy and BP, the project will use existing and newly built pipelines to send some 10 million tonnes of CO2 per year for storage in the Southern North Sea Viking gas fields.

Since the early 2000s, oil companies have worked with the government, researchers, and trade groups to show how CO2 captured from such projects could be used to squeeze more oil out of dwindling North Sea fields, while permanently storing the gas, the documents reviewed by DeSmog, and published on Climate Files, show.

But there has always been one big obstacle to implementing this vision: the UK’s failure to build any carbon capture capacity — despite two decades of trying.

In a 2003 white paper setting out the UK’s climate strategy, then Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Labour-led government set a target to reduce emissions by 60 percent by 2050, using carbon capture and storage to clean up the then coal-dominated power sector. The paper proposed setting up a consultation aimed at establishing an offshore demonstration project to show how the captured CO2 could be used to slow the long-term decline of North Sea oil production.

“We will therefore set up an urgent detailed implementation plan with the developers . . . to get a demonstration project off the ground,” the white paper said.

In 2005, BP proposed to convert the existing Peterhead gas-fired power plant near St Fergus in Scotland to run on hydrogen made using North Sea gas. The plant would have captured the resulting CO2, and then injected the gas into the offshore Miller oil field to extend production by two decades.

“This project offers this country an unrivaled and rapid opportunity, once sanctioned by government, to demonstrate CCS technology on a substantial scale and will give the United Kingdom the chance of becoming a global leader in the whole area of CCS and low carbon energy generation,” BP staff wrote in a memorandum to Parliament.

The plans never materialised.

In 2007, the Labour government launched a carbon capture and storage demonstration competition. Then in 2009 it announced a commitment to support up to four similar demonstrations over the following decade to enable “wider deployment” of CCS through the 2020s. The Conservative-Liberal coalition reaffirmed these commitments after it assumed power in 2010.

As with many carbon capture projects elsewhere in the world, cost-overruns proved fatal. The government cancelled the first demonstration competition in 2011 because it could not be funded within its £1 billion budget. A second £1 billion competition was launched in 2012 but cancelled four years later due to concerns about future costs for consumers, ratepayers, and the Treasury.

‘Profitable Business’

Despite the stalled progress, throughout 2013 and 2014, then Prime Minister David Cameron’s Conservative-led government began developing new strategies to boost oil and gas production from the North Sea, including the potential use of CO2 captured from coal-fired power plants for enhanced oil recovery.

Meanwhile, industry pressed its case that using captured CO2 to extend the life of North Sea oil and gas fields could raise the additional revenue needed to finance a rapid roll-out of carbon capture projects.

“CO2–[enhanced oil recovery] is the most significant method by which extra oil production can be combined with beneficial use of the CO2 captured by CCS at power plants and industry.”

CO2 Storage and Enhanced Oil Recovery in the North Sea: Securing a low-carbon future for the UK

In June 2015, Scottish Carbon Capture and Storage, the independent research group, published the industry-sponsored report (cited above) arguing that enhanced oil recovery could extract an additional three to six billion barrels of oil. An accompanying video (below) identified about 20 offshore sites deemed suitable for the technique.

“CO2–[enhanced oil recovery] is the most significant method by which extra oil production can be combined with beneficial use of the CO2 captured by CCS at power plants and industry,” the report found.

The report’s authors mapped out a scenario where enhanced oil recovery could be used to economically extract a billion barrels of oil while storing approximately 550 million tonnes of CO2 — roughly the annual emissions of Pakistan today.

To make the approach carbon negative, the systems used to capture the CO2 from industry, pipe the gas offshore, and then inject it into oil wells, would have to be kept running for years after the last oil was pumped from that field. The goal would be to both offset the emissions from burning that additionally produced oil, and then continue to fill the now former oil reservoir with captured CO2.

In a supporting presentation, Stuart Haszeldine, a professor of carbon capture at the University of Edinburgh, and director of Scottish Carbon Capture and Storage, argued that carbon capture and enhanced oil recovery could “be combined, profitably and environmentally.”

“CO2 injection can become a climate solution if you continue the CO2 injection beyond the oil production,” Haszeldine told DeSmog in an interview last November. “You could spend another five, 10 or 15 years just injecting neat CO2 for total storage, making the whole system become carbon negative. Inevitably this will need clear regulation which is strongly enforced to ensure that oil and gas producers do not evade their responsibilities.”

Critics of that argument fear oil companies will see little incentive to undertake the costly business of storing more CO2 than is needed to push out the last oil and gas from any particular field.

“It looks like a green concept,” said Aled Fisher, North Sea senior research campaigner at Oil Change International. “But when you build out loads of capacity and infrastructure, and then you realise there isn’t either enough carbon, or money for storing the carbon, you end up with an incentive to do [enhanced oil recovery].”

Despite such concerns, the UK’s Climate Change Committee, an independent body that advises the government on tackling climate change, also considered whether selling CO2 for enhanced oil recovery could help finance carbon capture projects.

“Funding [for carbon capture and storage] should be accompanied by a strategic approach to infrastructure development,” the committee wrote in a report on scenarios for decarbonising the power sector published in October 2015. “That . . . should also include consideration of the potential for Enhanced Oil Recovery.”

The Climate Change Committee told DeSmog earlier this year that it had “not developed this position further.”

‘Narrow Time Window’

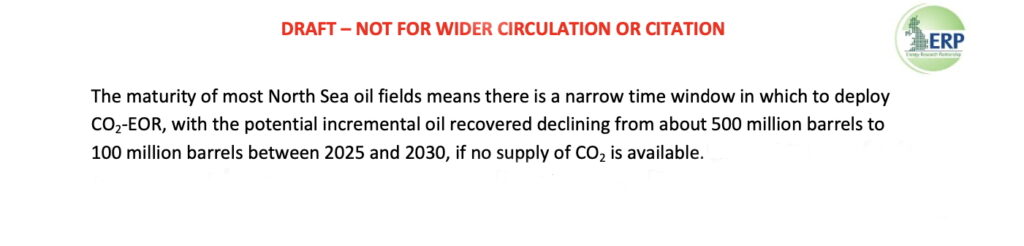

Meanwhile, the Energy Research Partnership, a public-private industry group with a steering committee chaired by a Shell executive, concluded in a draft report that injecting CO2 could theoretically recover an additional six billion barrels of North Sea oil — with storage space for more than one billion tonnes of CO2. The authors cautioned, however, that less than 10 percent of that recoverable oil would likely be economical to extract.

Nevertheless, the authors warned that the clock was ticking to deploy enhanced oil recovery to pump additional oil, and potentially extend the life of mature fields by 15 years, before operators began to decommission them.

“The maturity of most North Sea oil fields means there is a narrow time window in which to deploy CO2-EOR, with the potential incremental oil recovered declining from about 500 million barrels to 100 million barrels between 2025 and 2030, if no supply of CO2 is available”, the report, also drafted in 2015, states.

The Oil and Gas Authority, a regulator tasked with maximising North Sea production, referenced the Energy Research Partnership report in a strategy document on enhanced oil recovery published the following year.

Shell also continued to study the technique. In 2017, Stephen Goodyear, then Shell’s enhanced oil recovery deployment lead, prepared a presentation marked “restricted,” outlining the potential for the approach to be used offshore, without specifying which locations the company had in mind.

“Shell has been active in pushing next generation CO2 EOR projects,” the presentation says. “Studies show offshore CO2 EOR can be technically and economically feasible.”

In 2019, the Oil and Gas Authority found in an interim report that using CO2 for enhanced oil recovery might enable more than a billion barrels of additional oil production, while providing capacity for some 500 million tonnes of CO2 storage.

Later that year, the Oil and Gas Authority announced it would provide more comprehensive guidelines for using CO2 for enhanced oil recovery in a strategy report due to be published that autumn.

What actually emerged during the summer of 2020, was the UK’s most comprehensive blueprint for carbon capture and storage to date. These plans echoed earlier recommendations to develop the Acorn, Viking and other carbon capture projects, but made no reference to using captured CO2 for enhanced oil recovery.

Renewed Calls

Technical consultants continued to press the case for financing carbon capture by using captured CO2 to extract more oil.

Vysus Group, an engineering consultancy, concluded in 2021 that, given their previous research commissioned by the Oil and Gas Authority, the role of enhanced oil recovery in making carbon capture economically viable “should not be overlooked.”

“EOR may be a driver . . . in commercialising CCS,” Vysus states in Lessons 15 Years On: Commercialising Offshore Carbon Storage. “Initial projects that pin success on minimal viable development look most promising.”

Vysus has since begun reviewing the UK’s North Sea oil projects to help the regulator, since renamed the North Sea Transition Authority, independently assess remaining undiscovered resources, according to the company’s website.

In a further indication that industry was exploring the potential for enhanced oil recovery in the North Sea, the Journal of Petroleum Geology reported in June 2022 that Shell had considered using CO2 captured from a planned facility at the Jackdaw field to pump more oil. According to the report, Shell abandoned the idea after concluding it lacked a suitable nearby platform to handle the gas.

Nevertheless, Shell continues to advertise the potential scope for using CO2 to produce more oil. In a February 2022 press release announcing that its carbon capture technology had been selected for a project in the Humber region, Shell said the captured gas could “be sold, sequestered or used for enhanced oil recovery.”

Assuming the UK’s carbon capture plans proceed, Shell and ExxonMobil, a major player in enhanced oil recovery in the U.S., are poised to play key roles in storing that gas.

Since last September, the North Sea Transition Authority has awarded 21 offshore storage licences, mostly in mature oil and gas fields, to 14 different companies. Shell received three of these and will partner with Exxon on two others. Already a leader in combining carbon capture with enhanced oil recovery in the United States, Exxon has since bolstered its position by completing a $5 billion acquisition of smaller rival Denbury, one of the biggest enhanced oil recovery players.

‘No Plans or Projects’

Despite their two decades of researching the potential for enhanced oil recovery in the North Sea, oil companies dismiss fears that the UK’s carbon capture projects could be harnessed to pump more oil and gas.

Shell and Harbour Energy, developing the Acorn carbon capture in northeast Scotland, both told DeSmog in separate statements that they had no plans to use the captured CO2 to recover more hydrocarbons.

“Shell currently has no plans or projects to do CO2 [enhanced oil recovery] anywhere in the world,” Shell spokesman Paul Connolly said.

Harbour Energy said: “Harbour’s CCS projects are for transportation and storage only and do not involve enhanced gas or oil recovery.”

BP, which is working with Harbour Energy to develop the Viking carbon capture project on the Humber, did not respond to a request for comment. BP says on its website it delivers more oil with enhanced oil technology than any other international oil company. The company announced last September that it is investing in an Indonesian carbon capture project that will use the captured CO2 to extract natural gas.

Norway’s Equinor, which is developing the Rosebank oil and gas field, also said it had no plans to use the technique in the UK or anywhere else. “We have never used CO2 for [enhanced oil recovery] and have no plans to ever do it,” said Equinor spokesman Ola Morten Aanestad.

Exxon said it had sold its oil-producing assets in the North Sea a few years ago, and any questions on enhanced oil recovery should be referred to companies that are still pumping oil from the basin.

While these oil majors have denied interest, industry documents suggest that independent operator Ithaca energy is considering using captured CO2 for its Captain project in the North Sea, which is currently using other enhanced oil recovery methods to extend the life of this field. The International Association of Oil and Gas Producers, a lobby group, said in a briefing document dated last October that Scotland’s planned Caledonia Clean Energy carbon capture and storage project is evaluating whether to send CO2 to the Captain field for enhanced oil recovery. Ithaca did not respond to a request for comment.

The Carbon Capture and Storage Association said it was not backing any enhanced oil activities, which would, in any case, require different permits to the storage licences issued since September.

“For the UK, we do not yet have any operational CO2 storage sites, despite this being urgently needed by our domestic industry, so we believe that should be the priority,” the group said in a statement.

The UK government’s Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, and the North Sea Transition Authority regulator, each issued identically worded statements saying that “there are currently no active or planned CCS schemes which use CO2 for enhanced oil recovery (EOR) in the UK.”

“I don’t trust the oil companies at all when they say that they’re going to inject into a reservoir that is a reasonable site for enhanced oil recovery, but they’re not going to recover the oil?”

Charles Harvey, professor, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Such reassurances have done little to allay concerns among critics, who point out that almost 80 percent of the world’s estimated 51 million tonnes of operational carbon capture capacity is used for enhanced oil recovery – the only large-scale market for the gas. With some 41 carbon capture and storage projects operational worldwide, 29 are used for enhanced oil recovery, according to industry data.

Without resorting to enhanced oil recovery, climate advocates question how the UK will finance the multi-billion-dollar projects needed to hit its carbon capture targets.

“I don’t trust the oil companies at all when they say that they’re going to inject into a reservoir that is a reasonable site for enhanced oil recovery, but they’re not going to recover the oil?” said Charles Harvey, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who once founded and ran a carbon capture company. “And that’s the bigger point: We don’t want to keep producing oil. So the last thing we want to do is subsidise oil production in a way that makes oil cheaper.”

Government Backing?

Perhaps the bigger question looming over the controversy around carbon capture in the UK is whether – after years of false starts – companies may prefer to invest in more stable and lucrative markets elsewhere.

U.S. President Joe Biden’s landmark 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, hailed for its climate provisions, turbocharged subsidies for all forms of carbon capture — including by raising the tax credits for CO2 stored via enhanced oil recovery to $60 per tonne of CO2, from $35 per tonne, sparking a wave of investment.

Industry experts said the UK government might be tempted to back enhanced oil recovery on the grounds it would boost tax revenues, and be cleaner than importing liquefied natural gas from North America, a process rife with methane leaks.

But given the outcry over Sunak’s authorisation of new oil and gas licences, industry representatives say the government may hesitate to endorse the use of captured CO2 to pump more oil – even if there are no legal or regulatory hurdles to doing so.

“There’s no doubt at all, that if anyone was to come forward with a request for public funding of some kind supporting an [enhanced oil recovery] project, there’d be a wall of political resistance to the idea,” said Chris Davies, director of CCS Europe, a trade group representing companies such as Baker Hughes and Air Liquide, which build carbon capture and transport systems. “So I think our members would be generally resistant to the idea of supporting a technology which would seem to reinforce the criticisms of CCS voiced by the environmentalists.”

Given the UK’s 20-year history of failed carbon capture projects, analysts fear that the latest round of announcements of ambitious targets will serve primarily to give oil companies a licence to continue doing what they have always done: pump as much oil and gas as they can.

“The evidence is that they’re hiding behind [carbon capture and storage] rather than actually wanting to make it work,” said Chris Littlecott, associate director of fossil fuel transition at climate consultancy E3G. “Many projects have been proposed but ultimately haven’t come into operation because a company would never move forward with a final investment decision.”

Additional reporting by Andrew Kersley and Edward Donnelly

This story was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts