For money managers who want to prove they care about the climate, buying shares in big advertising and public relations companies might look like a safe bet.

Ad giants such as WPP, Omnicom and Interpublic Group (IPG) score highly on the rankings used to gauge a company’s sustainability performance — so they’re attractive to green fund investors.

However, a DeSmog investigation has found that these scores take little or no account of multiple risks associated with the advertising and PR industry’s role in the climate crisis — from reputational damage caused by greenwashing fossil fuel clients, to threats to staff retention, and the danger of being sued for climate damages.

And DeSmog can also reveal that a growing group of ethical investors are demanding that ad and PR companies come clean about their true climate impact.

Although the communications industry has mostly sidestepped the kind of scrutiny traditionally reserved for oil and gas companies, the investors’ concerns show calls for climate accountability in the sector are getting louder. An outpouring of criticism of French ad giant Havas — a self-styled climate leader — for taking a global media buying contract with oil major Shell is another clear indicator of this trend. Critical commentary in the trade press after news of the deal broke five months ago — and mockery from influencers — marked a watershed moment in an industry where such deals had rarely been considered through a climate lens.

Now, the investors are piling on the pressure. Led by Inyova Impact Investing, a Swiss-German fund manager, the coalition includes the US$1 billion-plus Future Super fund in Australia; Erste Asset Management, one of the largest in Austria; Boston Trust Walden, a U.S. fund manager; French managers Ecofi and Sycomore Asset Management; and a UK investment manager that has yet to go public with its support.

Such investors rely on ESG — environmental, social and governance — scores created by ratings agencies to assess a company’s exposure to financial risks associated with issues from its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, to human rights violations in its supply chain, and executive pay.

High ESG scores mean that three of the global big-six ad companies — Publicis, IPG and Dentsu — are included in the feted Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI), which ranks them alongside tech giants such as Microsoft and Alphabet.

That makes it easier for these companies to raise money from large pools of pensions and savings, who look for high ESG scores and inclusion in indices like the DJSI to decide which companies count as “sustainable” investments.

But Inyova and its allies say that the role advertising and PR companies play in supporting the fossil fuel industry to portray itself as greener than it actually is poses risks that could hit their bottom line.

The dangers range from potential legal liability for climate harms, damage to brand credibility, growing scrutiny from regulators, and the risks that other major clients won’t want to be seen alongside polluters on the rosters of big ad firms. Importantly, fossil fuel deals could also hit employee retention in a sector where the average age of staff is 34, and hiring the best creative minds from an environmentally conscious younger generation is key to staying in business.

The investors say that none of these risks are being reflected in the advertising and PR companies’ rosy ESG scores.

“There is a lot of risk of legal challenges to advertising companies these days as countries tighten up greenwashing regulations,” said Andreas von Angerer, head of impact at Inyova, which manages $284 million for about 10,000 Swiss and German retail investors.

Green Tinge

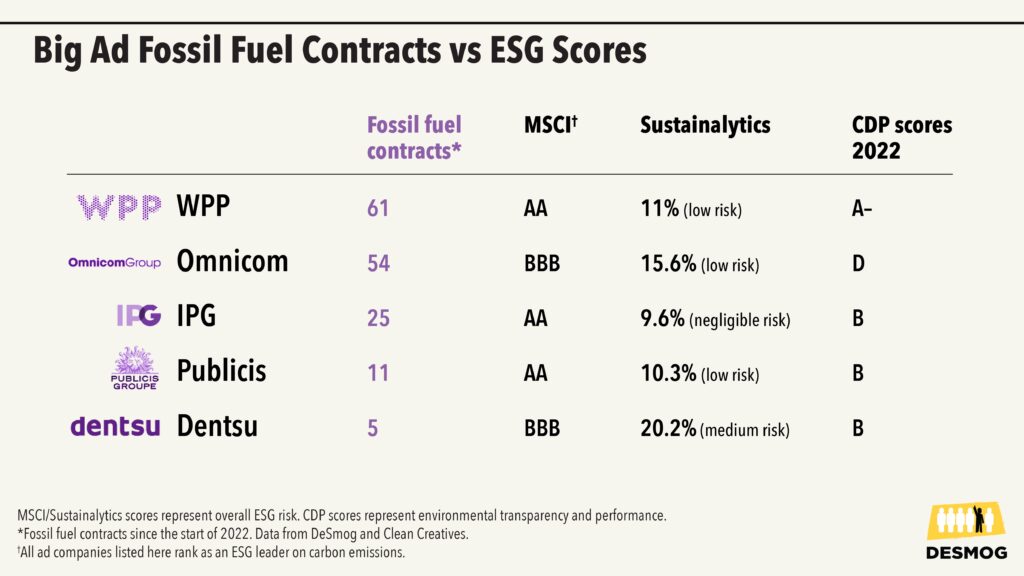

The new research by DeSmog shows that big ad companies score well on environmental risks from some of the big ESG raters (see graphic) despite their ties to oil and gas.

The ESG scores of five of the world’s biggest advertising agencies, WPP (UK), Omnicom (U.S.), Publicis (France), IPG (U.S.) and Dentsu (Japan) are either relatively high, or considered low risk.

Havas, the French giant, which is one of the global big-six, is not a public company, therefore does not get an ESG rating. However, its parent company, Vivendi, is reportedly considering a Havas listing.

MSCI, a leading ratings company, ranks firms on ESG performance from AAA — CCC, high to low. It scores WPP, Publicis and IPG as AA. Omnicom and Dentsu score as BBB. MSCI ranks all five as ‘ESG Leaders’ for carbon emissions. Sustainalytics, an ESG ratings firm owned by Morningstar, a funds data company, scores IPG as a negligible ESG risk, Omnicom, WPP and Publicis low risk, and Dentsu medium risk.

The scores are relatively consistent across a range of ESG raters, according to DeSmog’s research.

CDP, a widely used reporting platform for corporate CO2 emissions, also scores four of the big ad firms as B or above (on a scale of A to F) for environmental reporting (see chart), meaning, “they have addressed the environmental impacts of their business and are doing well on environmental management.”

The ad companies use these green investment scores to burnish their own environmental credentials in the eyes of investors, potential clients, and their staff, even as they continue to do PR, advertising, and marketing work for some of the world’s biggest polluters.

DeSmog research shows WPP agencies held a combined 61 contracts with fossil fuel clients across 2022 and 2023 with oil majors including BP, Shell, Chevron, and Saudi Aramco, as well as lobbies such as the American Petroleum Institute (API). This was the most fossil fuel contracts of the five companies in DeSmog’s analysis, despite WPP’s pledge to reach net zero emissions in its operations and supply chain by 2030. Yet, it has a top ESG rating from CDP.

Omnicom’s 54 fossil fuel contracts during the same period included TotalEnergies, ExxonMobil, and a $3.8 million project for an oil and gas lobby called the Canadian Energy Centre. But Sustainalytics rates it as “low-risk.”

WPP and Omnicom topped the 2023 F-list of advertising and PR companies that work with fossil fuel clients, published annually by industry campaign group, Clean Creatives. According to the report, IPG and Publicis followed with 25 and 11 contracts respectively over the past two years.

Along with Dentsu (five fossil fuel contracts), these five companies dominate the communications industry, owning hundreds of subsidiaries around the world and generating combined revenues of $64 billion in 2022.

Ratings agencies say the ‘E’ scores in ESG are designed to evaluate a company’s exposure to environmental risks threatening their operations or supply chains — not their impact on the climate and environment.

“MSCI ESG Ratings are fundamentally designed to measure a company’s resilience to financially material environmental, societal and governance risks,” a spokesperson for MSCI ESG Research said in a statement. “They are not designed to measure a company’s impact on climate change.”

Jennifer Vieno, who manages technology, media and telecommunications research at Sustainalytics, said that working for fossil fuel clients would not expose advertising and PR companies to greater near-term risks from environmental or climate shocks.

“The provision of PR services for fossil fuel companies will not increase their own direct environmental risks,” Vieno told DeSmog.

However, Vieno added that, “One potential risk is these companies may lose current clients or be unable to attract certain clients due to their provision of these services.” Another could be on the human capital front, for the same reason. “There are other potential regulatory risks.”

When news broke of Shell’s deal with Havas in September, the Fossil Fuel Nonproliferation Treaty campaign immediately terminated its relationship with the agency. Protestors staged a die-in and a subsequent action at Havas headquarters in London.

WPP declined to comment. Omnicom, Publicis, IPG and Dentsu did not respond to requests for comment.

‘Dictated by the Client’

All five companies in DeSmog’s analysis are members of an initiative called Ad Net Zero, founded and run by the Advertising Association, a UK-based advertising industry lobby group.

Members sign up to a five-step action plan to reduce emissions from business operations, supply chains, advertising production and placement, and events, by setting net zero targets verified by the Science-based Targets Initiative (SBTi), regarded as among the most credible monitors of corporate climate commitments. Ad Net Zero also encourages signatories to promote sustainable consumer behaviour through ads and PR campaigns.

However, critics of the initiative say it takes little account of the wider climate impact of agencies’ work for fossil fuel clients, or their role in driving up demand for unsustainable products such as SUVs, cheap flights, throwaway plastic and fast fashion. A DeSmog investigation in January found that three-quarters of the awards given to agencies at the Ad Net Zero awards — founded to “highlight environmental sustainability in the advertising industry” — went to those who also work for fossil fuel clients. Neither does SBTi require ad and PR companies to factor in the possible climate impact of their campaigns on behalf of polluting clients into their progress towards net zero targets.

“I do think there is a big blind spot here,” one investor, who did not want to be publicly quoted while lobbying the ad companies, told DeSmog. “These ad companies have science-based targets for net zero that have been validated by SBTi, but without the inclusion of their clients’ emissions. Yet these companies have a huge influence on their clients.”

SBTi did not respond to a request for comment.

In their defence, the big ad companies argue that they are helping polluters transition to net zero.

When campaigners and employees expressed their dismay at Havas for winning Shell’s media buying account, CEO Yannick Bolloré sought to allay staff anger by presenting the deal as an opportunity to change the oil major from within.

Top executives at other major advertising companies, such as WPP CEO Mark Read, have advanced similar arguments.

But employees involved in the day-to-day business of client relationships doubt that PR and advertising agencies can have much influence over an oil and gas company’s business model.

“Agencies are helping clients on their transition journeys — as dictated by the client,” said one employee of a major advertising firm covered in DeSmog’s analysis, who asked not to be named for fear of professional repercussions. “We subscribe, promote, and defend the transition plan the client wants for the world, not for what the climate science demands.”

Shield from Scrutiny

Evidence that ad companies are helping to mask climate inaction by oil and gas companies has sharpened investor concerns.

The World Benchmarking Alliance, which assesses 2,000 of the most influential companies on their contributions to the UN Sustainable Development Goals, said in June last year that, since 2021, “the oil and gas sector has made almost no progress” towards aligning with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

Nevertheless, oil and gas majors invested more than $1 billion in shareholder funds on “misleading climate-related branding and lobbying” in the first three years after the Paris Agreement was signed, according to InfluenceMap, a nonprofit that tracks corporate lobbying. InfluenceMap says these companies also spend hundreds of millions of dollars each year on “a systematic strategy to portray themselves as positive and proactive on the climate change emergency”.

In 2022, the UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change pointed to the role of the communications industry in the climate crisis for the first time, finding that fossil fuel PR and marketing uses “climate-care statements” and “deflect[s] corporate responsibility to individuals” rather than governments and corporations.

In light of those findings, UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres told the UN Assembly: “We need to hold fossil fuel companies and their enablers to account. [This] includes the massive public relations machine raking in billions to shield the fossil fuel industry from scrutiny.”

A survey by Comms Declare, a climate advocacy group created by ad communications professionals, found that 73 percent of employees in the industry are hesitant to work with fossil fuel clients, while 67 percent think their agencies should take a stronger stand against such companies. Meanwhile, Clean Creatives has persuaded over 900 ad agencies worldwide to pledge to not work with fossil fuel clients at all.

Such disquiet could pose a significant business risk because staff costs account for 63 percent of total ad company expenditure, according to a new report on the sector by financial think tank Planet Tracker.

The report also warns that climate-related reputational risks could hit the “goodwill” that ad companies include on their balance sheet to represent intangible assets, such as brand quality, which can account for as much as 40 percent of a company’s value.

“Clearer measurement and reporting by advertising agencies regarding their clients’ environmental footprint scores are crucial to enable investors to make more informed decisions,” said John Willis, director of research at Planet Tracker.

“What matters is not just the ‘internal’ footprint of the agency, but also the ‘external’ footprint they promote, such as the widespread continued support of Big Oil, fast fashion, or plastic pollution,” Willis adds. “This raises the possibility that advertising holding companies are being included in ESG funds due to ‘positive’ ESG scores. We are concerned that investors might be ‘looking the wrong way’ and not taking in the whole picture.”

‘Advertised Emissions’

Increasingly, ad industry insiders and activist investors are making common cause in trying to quantify more of the advertising industry’s true climate impact through a concept known as “advertised emissions”.

The approach mirrors the now widely accepted concept of “financed emissions”, which seeks to quantify the amount of greenhouse gas emissions associated with the loans and investments made by banks in fossil fuel and other polluting companies.

Purpose Disruptors, a campaign group started by ad-industry professionals, and Magic Numbers, a London-based econometrics agency, developed the advertised emissions concept to apply a similar methodology to estimate emissions from the rise in product sales generated by advertising.

Although the approach does not yet attempt to assess the impact of non-advertising services — such as branding, public relations, and lobbying for fossil fuel giants — the developers see it as a natural extension of the industry’s established practice of attempting to quantify the contribution it makes to driving sales.

Using data from the Advertising Research Community, which measures advertising’s return on investment for campaigns in the UK, Purpose Disruptors says advertised emissions have risen in the UK by 11 percent between 2019 and 2022 to reach 208 million tonnes of CO2. That makes advertising partly responsible for 32 percent of the carbon footprint of every single person in the country; or the equivalent to running 56 coal-fired power plants for a year.

The ad industry has pushed back. The three main UK-based industry associations wrote a joint article in Campaign magazine last year arguing that adopting the measure would lead to “a significant overstating of emissions” by ignoring advertising‘s “displacement effects” — whereby the sale of one product or service means the lost sale of another.

Nevertheless, Japan’s Dentsu published an estimate of its advertised emissions in its 2023 report for the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures, a global framework for reporting climate risks. Denstu found that its advertised emissions were 32 times higher than its operational emissions, which include sources such as powering offices and staff travel.

Growing Coalition

Concerned about potential hidden climate risks in advertising and PR firms, Inyova, the Swiss-German investor, initially called for other investors to sell their shares in the sector.

Invoya’s Von Angerer said that tactic got push-back from big investors.

Ten of the world’s biggest money managers, including BlackRock and Vanguard, own on average 49 percent of the shares of the five listed advertising companies, according to the Planet Tracker report.

So Inyova changed tack. Last year, it lobbied Publicis, the French ad giant, to use the “advertised emissions” methodology in its carbon accounting via a campaign coordinated on the investor engagement website of the United Nations-supported Principles for Responsible Investment, which represents 5,372 investors managing assets of $121.3 trillion.

Publicis adopted the standard industry defence when responding at its annual general meeting of shareholders in May last year by saying that its clients — who include Shell, TotalEnergies, and Saudi Aramco — are transitioning to a low-carbon economy.

After presentations at big U.S. investor coalitions, the Interfaith Centre on Corporate Responsibility and Ceres, as well as the French Responsible Investment forum, the number of campaigning shareholders has grown.

The investors are now seeking meetings with the climate change heads at the big ad companies to get them to analyse the climate impact and transition plans of high-carbon clients as part of contract negotiations, and to reject those that are not aligned with the 1.5C Paris Agreement target.

Von Angerer is realistic, though, about the hurdles to investor action: “One large shareholder we spoke with was concerned about the risks, but, after evaluation, said the climate data gave the ad companies a clean bill of health.”

Nevertheless, a number of initiatives are seeking to develop more granular methodologies to capture the true climate impact of the advertising and PR industry, as well as other service sectors, such as accounting and management consultancy.

The Law Society of England and Wales has developed guidance for its members with a section on ‘advised emissions’.

And the United Nations Climate Change High-Level Champions initiative has backed a research project by Oxford University and the Race to Zero campaign on serviced emissions — associated with consultancy, legal and advertising firms. It advises signatory ‘champions’ to understand and reduce serviced emissions and then publish the data alongside conventional greenhouse gas reporting.

Reputational Risks

ESG ratings have themselves emerged as a battleground in the U.S., where right-wing forces have sought to discredit attempts by investors to assess climate risk.

Nevertheless, big ad companies look likely to face further pressure to report the advertised emissions of their clients. For now though, that information will not appear directly in their ESG scores — although it could start to generate red flags.

Vieno, the Sustainalytics research manager, said that taking on fossil fuel clients could trigger what is known as ”controversy research” — which factors the damage caused by negative headlines into a company’s ESG score. “Reputational risks from allegations of greenwashing for example can be captured under certain controversy categories such as marketing practices and media ethics,” Vieno said.

“It will be interesting to see what occurs on the environmental litigation front: Will the industry experience a similar increase in climate-related probes and litigation as has been seen for banks over the past few years? That has not been the case to date but we will reassess as new developments occur.”

Separately, the investor who has been engaging with advertising companies said the next step could be to build on the example set by Dentsu — the Japanese holding group that estimated its advertised emissions — by filing resolutions at annual general meetings urging its rivals to follow suit.

“I don’t think there are enough big investors to file a resolution yet,” the investor said. “But I think that in a year or two we could see a shareholder vote seeking the same kind of disclosure on advertised emissions as Dentsu have done…We believe that ad companies’ reputations in terms of their long-term commitment to the energy transition are at stake.”

Additional reporting by Ellen Ormesher.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts