Photos I shot last year in South Louisiana illustrate the Gulf Coast’s rapidly expanding fossil fuel industry, and the groundswell of frontline community members, environmental advocates, and activists fighting to stop it.

While climate impacts intensify along the Gulf Coast, the Louisiana, Texas, and federal governments are poised to permit a growing number of proposed hydrogen manufacturing facilities equipped with carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) technology, and liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals. The projects under consideration, if permitted, not only will contribute to climate-warming emissions, but also will be vulnerable to the very climate impacts the projects will exacerbate.

This selection of images counters fossil fuel industry narratives that expanding the United States’ capacity to export LNG and increasing the demand for hydrogen fuel and the development of CCS technology benefit the public — and the climate. The photographs highlight the contradiction between the Biden administration’s stated agenda to combat the climate crisis and its policies that increase global reliance on fossil fuels.

“Clean” hydrogen and carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) play a major role in the climate agendas of former Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards (D) and President Joe Biden. Both are rich with ambitious pledges of striving for net-zero emissions by 2050 and tout subsides for hydrogen energy and the development of CCS technology as essential to transitioning to renewable energy, despite mounting evidence that these technologies extend lifelines to the fossil fuel industry.

The real test is whether the government is taking measurable actions to limit climate emissions and impacts, and preliminary results are not favorable. In 2023, U.S. oil production and LNG exports were higher than ever, as were record-breaking global temperatures.

Climate strategies that create a broad demand for hydrogen fuel instead of transitioning to renewables and electrification largely serves the fossil fuel industry because, at the moment, it will increase the demand for methane, the primary component of natural gas, while promising to capture emissions for so-called “blue” hydrogen. While “green” hydrogen fuel can be produced with renewable energy, that process is cost prohibitive for now. Almost all of the hydrogen fuel used today requires natural gas in the manufacturing process, and despite significant investment, CCS projects have failed to live up to their ambitious promises.

“If the U.S. Department of Energy used more realistic numbers in its analyses, it would be clear that blue hydrogen is an extremely dirty alternative,” stated David Schlissel, the director of the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, which recently published a critical report on blue hydrogen.

Throughout the year, I followed the ongoing fight against Air Products’ massive $4.5 billion “blue” hydrogen manufacturing complex and accompanying CCS hub proposed in South Louisiana. Though it will add climate warming-emissions and put at risk the fragile estuary ecosystem where it is developed, it is the kind of project that fits into both Edwards’ and Biden’s climate agendas that are steeped in cognitive dissonance.

Air Products, a global hydrogen manufacturing firm, and fossil fuel companies with plans to get into the hydrogen and carbon capture markets are poised to benefit from billions of dollars in funding and tax credits earmarked to support climate initiatives in both the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act.

At the end of December, the U.S. Treasury Department offered proposed rules for “transformative clean hydrogen incentives.” They lay out the conditions for companies to benefit from energy credits for developments producing “clean hydrogen” fuel. Public comments on the proposed rules close February 26.

Another major development that came over the holidays was the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) decision to hand over authority to permit CCS projects to the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources (LDNR), despite over 40,000 public comments in opposition.

“State regulators are the most equipped to make permitting decisions on injection wells,” Patrick Courreges, spokesperson for the state, explained to me in 2021 when the agency made the request to EPA to regulate CO2 injection wells. The state, he said, is poised to expedite the permitting process for the expected influx of CCS project applications once generous financial incentives became available.

Some opponents see Louisiana’s intention to speed up the permitting process as a reason to deny its request. “We are braced for a flood of permit approvals by an agency that is not adequately staffed or resourced to provide the oversight and accountability that Louisiana residents demand and deserve,” Logan Burke, executive director for the Alliance for Affordable Energy, said in a press release following the EPA decision.

Louisiana officials welcomed the announcement. Then Gov.-elect Jeff Landry (R), who was sworn in on January 7, 2024, tweeted his approval of the EPA’s decision, describing it as a significant milestone in Louisiana’s economic development. “This approval has positioned Louisiana to become the nation’s leader in safely storing carbon dioxide, contributing to nationwide emissions reduction and bringing new jobs and innovation to our state.” Landry’s campaign platform included “fighting the Biden Administration to unleash Louisiana’s oil and gas production and bring back America’s energy independence.”

“We certainly want Louisiana to be able to develop opportunities for economic growth in the emerging market for carbon management,” LDNR Commissioner of Conservation Monique M. Edwards said in a press release about the EPA’s decision. “But we cannot and will not sacrifice our duty to ensure that operations are conducted in a way that is protective of public safety and the environment.”

Beverly Wright, executive director of the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice, described the EPA’s decision to grant the DNR permission to permit the injection wells as “simply wrong.” Doing so, “leaves Louisiana’s most vulnerable exposed to an untested pollution control technology,” Wright said. “Adding to the potential harm is relying on the DNR, an agency with a track record of ignoring environmental justice concerns and failing to comply with environmental regulations for decades, to manage it all,” she added.

Members of other environmental advocacy organizations, including Earthjustice, the Center for International Environmental Law, and community groups in Cancer Alley that already face an elevated risk of cancer due to existing fossil fuel industry emissions, described the EPA’s decision as a betrayal of the Biden administration’s environmental justice and climate agenda.

The same day the EPA approved LDNR’s request, I received a call about a petroleum-based drilling mud spill by Air Products near the site where the company is working on a test well to inject CO2 under Lake Maurepas.

I contacted Greg Langley, the spokesperson for Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ), to find out what caused the spill and what in the drilling mud might be toxic. His email reply states: “Because it was a minimal amount (one barrel), was contained quickly, and was of low toxicity, it was not considered a threat to wildlife.”

Langley didn’t provide me with the specifics I was after. Though regulators eventually will post an online incident report, that may not have these details either. This interaction illustrates how difficult it can be to obtain relevant information for fossil fuel industry projects.

While spilling one barrel of drilling mud will not create widespread environmental issues, it was large enough for Air Products to report it, and the construction of a much larger CCS hub brings the risk of much greater harm to the ecologically sensitive lake above it.

Air Products maintains that it will restore any environmental issues caused during construction and that its proposed blue hydrogen manufacturing complex will “reduc[e] the amount of carbon dioxide that is released into the atmosphere using [a] safe and proven engineering technology called carbon capture and sequestration.”

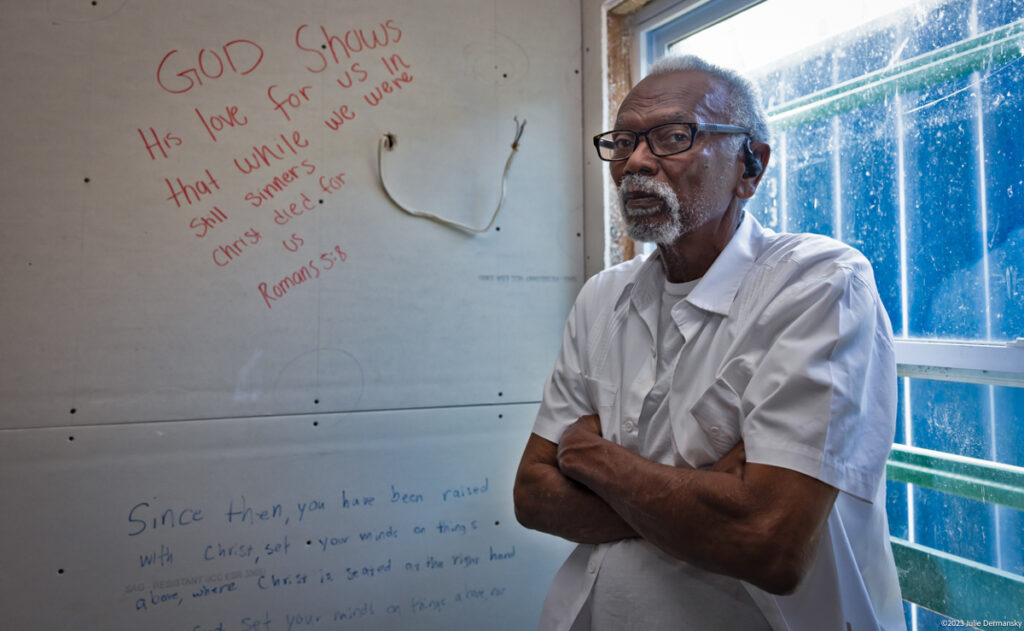

Robert Taylor — a community leader in St. John the Baptist Parish — is part of a coalition that opposed Air Products’ project. If the company’s plans are realized, his home will be between the hydrogen manufacturing facility and the CCS hub. “Cancer Alley is already overburdened with toxic pollution,” he told me on a call voicing his disapproval of the EPA’s approval of DNR’s request.

Taylor, who was chosen to be a hub leader in the Biden administrations “Justice40” initiative, had hoped that the administration would protect his and other Louisiana frontline communities from toxic emissions but he says those hopes crumbled when an EPA civil rights investigation into the LDEQ and the state’s health department closed in June without finding any wrongdoing by those agencies.

In October of 2022, the EPA sent both agencies a highly critical 56-page letter that notified them that its preliminary findings found merit in the complaints Taylor’s group, The Concerned Citizens of St. John, and other environmental advocacy organizations made against them for their dealings with minority fenceline communities in Cancer Alley.

Before the year ended, EarthRights International, a nonprofit human rights organization based in Washington, D.C., filed a civil rights complaint on behalf of the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation (formerly known as the Isle de Jean Charles Tribe) to the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The complaint asks that HUD investigate the Louisiana Office of Community Development’s (OCD) implementation of the Isle de Jean Charles Resettlement Program and asserts the state agency is undermining the human and cultural rights of the Tribe.

As I previously reported, the OCD, with the blessing of the Tribe, used its visionary resettlement plan for the state’s application to HUD’s National Disaster Resilience Competition years earlier. The Tribe’s proposal, coupled with the low-income, Indigenous status of its members who still lived on the island, helped the state win $92 million from HUD. About $48.2 million of that total was earmarked to resettle the Tribe from its namesake historic homeland, the Isle de Jean Charles, a rapidly dwindling island about 80 miles southwest of New Orleans at the edge of the Gulf of Mexico. Shortly after OCD secured the funds in 2016, the Tribe says the agency radically transformed its original proposal into a plan the Tribe no longer felt comfortable associating with.

OCD declined to comment on the complaint, according to NOLA.com. The agency previously justified the changes it made to the by explaining to DeSmog that limiting the project to a specific tribe could be seen as contrary to HUD’s rules and federal anti-discrimination laws.

Construction problems were evident in 2022 before Tribe members moved into the first OCD-produced homes built with federal funds. Though the state hails the resettlement project as a success, Tribal leadership consider the rollout of the resettlement project an example of environmental racism at its worst instead of a roadmap for other communities in need of relocation due to the climate crisis.

Travis Dardar is one of the a members of the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation who moved his family from Isle De Jean Charles to Cameron, Louisiana, years ago, as life on the island grew more perilous. A couple of months ago he felt compelled to move his family again. After Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass LNG export facility sprung up near to Dardar’s home, and the company announced plans to build another export facility even closer, he felt he had no choice but to relocate his family once again to another part of South Louisiana.

I met the Dardars at a Christmas party held by Fishermen Interested in Saving our Heritage (FISH), a nonprofit organization they established to raise awareness about threat the expanding the LNG export industry poses to fishermen along the Gulf Coast, as well as to provide them with direct aid. The Dardars and members of the coalition are actively pressing the Biden administration to deny Venture Global’s request to build another export terminal, called CP2, next to the one already in their community. The Federal Energy Regulatory Committee (FERC) is expected to decide on the CP2 LNG project soon.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts