Darren Woods, the CEO of Exxon, celebrates the potential of carbon capture to dramatically reduce global emissions. According to Saudi Aramco’s podcast, the fossil fuel industry is innovating new climate solutions, and BP’s podcast proclaims more of the same.

These messages sound like they’ve been pulled from the public-relations departments of the world’s largest oil companies, but they were produced and promoted by the in-house ad agencies of Bloomberg, Reuters, and The New York Times, respectively, and in the process benefited from the credibility those media brands have built with readers over the decades as trustworthy sources of news.

According to a new report by DeSmog and Drilled based on an analysis of hundreds of advertorials and events, as well as data from Media Radar, a service publishers use to track ad campaigns, many of the world’s most trusted English-language news outlets regularly lend their reputations to the fossil fuel industry’s messaging on climate-related topics. These range from the promise of proposed solutions such as carbon capture and “renewable biogas,” to the role the industry claims to be playing in the energy transition, despite its persistently low investments in anything other than increased fossil fuel production.

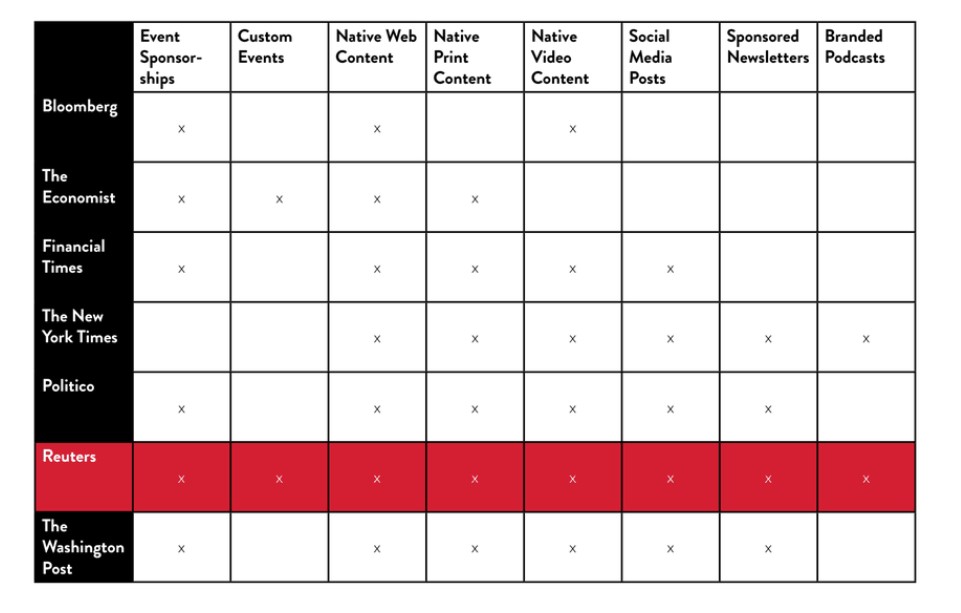

All of the companies reviewed — Bloomberg, The Economist, The Financial Times, The New York Times, Politico, Reuters, and The Washington Post — top lists of most-trusted news outlets in both the U.S. and Europe. Each has an internal brand studio that creates advertising content for fossil fuel majors that range from podcasts to newsletters, videos, and advertorials, and some allow fossil fuel companies to sponsor their events. Reuters goes a step further, with marketing staff creating custom industry conferences explicitly designed to remove the “pain points” holding back faster production of oil and gas.

This trend was on stark display as United Nations climate talks got underway in the United Arab Emirates on November 30, with oil and gas companies sponsoring a wealth of advertorials, newsletters and events with media partners, all designed to portray the industry responsible for the bulk of planet-warming emissions as the gatekeeper to climate solutions.

Mainstream media outlets defend the practice of creating news-adjacent content for advertisers — referred to as “native advertising” or “sponsored content.” However, climate advocates argue that when it comes to a complex and politicized issue like the climate crisis, the media should re-think this practice. Max Boykoff, who contributed research and analysis on the media’s role in climate action to the most recent report on reducing carbon pollution from the UN-backed Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), says the media plays a fundamental role in shaping the public’s and policymakers’ understanding of climate issues. “Everyday people aren’t picking up the IPCC report or peer-reviewed research to understand climate change,” said Boykoff, a professor of environmental studies at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where he directs the Media and Climate Change Observatory. “People are reading about it in the news, that’s what shapes their understanding. So the media are really just such influential shapers of public discussion on this subject.”

‘Tarnishes the Reputation’

Spokespeople for Bloomberg, the Financial Times, The New York Times, Reuters and The Washington Post (Politico did not respond to a request for comment) maintained that advertorial content is created by staff that are separated from the newsroom, and emphasized that their journalists are independent from their ad sales efforts. But the independence of these outlets’ reporters is not in question. At issue is whether or not readers understand the difference between journalism and advertising — and according to a growing body of peer-reviewed research, they do not. A 2016 Georgetown University study found that advertorials — also known as native advertising — are mistaken for “real” content by about two thirds of people. A 2018 Boston University study found that only one in 10 people recognized native advertising as advertising, rather than reporting. A 2016 study conducted by Stanford University researchers found that 80 percent of students mistook native ads for reported stories. That’s particularly important in the context of climate, where the sponsored content paid for by oil companies often directly contradicts the reporting.

Michelle Amazeen, the mass communications researcher who led the Boston University study, also found that those who did recognize sponsored content for what it was thought less of the outlet they were reading. “It tarnishes the reputation of that news outlet,” Amazeen said. “So it’s baffling to me why newsrooms are continuing to pursue this.”

“In theory, these complaints could possibly be addressed with better labeling and smarter design,” said Jay Rosen, a journalism professor at New York University. “But if you’re saying that even when they are properly labeled and carefully set off from the real journalism, these advertorials weaken trust and miscommunicate about climate change, that is a problem that cannot be solved within the industry consensus around sponsored content. It’s implicitly calling for a new consensus.”

Our analysis focused on the three years spanning from October 2020 to October 2023, a period when calls for the media, public relations and advertising companies to cut their commercial ties with fossil fuel clients have increased amid growing awareness of the role industry messaging has played in slowing climate action.

In September 2022, UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told the UN General Assembly: “We need to hold fossil fuel companies and their enablers to account [including] the massive public relations machine raking in billions to shield the fossil fuel industry from scrutiny.”

‘Align your Climate Narrative’ for COP28

This year’s annual UN climate negotiations, known as the 28th Conference of the Parties or COP28, are being held in Dubai, the largest city in the United Arab Emirates, one of the world’s top oil-producing countries. Presided over by Sultan Ahmed Al Jaber, the head of Abu Dhabi’s state oil company, Adnoc, it is the most industry-influenced COP yet.

Fossil-fuel companies, including Adnoc, are increasingly promoting carbon capture and storage, hydrogen, and carbon offsets as viable climate solutions, despite the enormous challenges in scaling them to a point where they might have any positive effect on the climate. As COP28 president, Al Jaber has backed these technologies in the lead-up to the summit.

Climate reporters at all of the news outlets we analyzed have diligently covered the challenges these approaches face. However, the research shows that when their reporting is placed alongside corporate-sponsored content touting the benefits of these technologies, it leaves readers confused.

A podcast that Reuters’ in-house studio Reuters Plus produced for Aramco this year focused heavily on these technologies, for example. In 2022, “The Energy Trilemma,” a podcast The New York Times’ T Brand Studio created for BP, touted how high-emitting industries are decarbonizing — mostly through technology, not by reducing the development or use of fossil fuels. Bloomberg Media Studios, meanwhile, created a video for ExxonMobil last year touting both carbon capture and hydrogen, particularly a project Exxon is involved with in Houston that aims to capture 100 million metric tons of carbon dioxide annually by 2040. In the video, Exxon CEO Darren Woods says the company is “ready to deploy CCS to reduce the world’s emissions,” but leaves out that the company also plans to increase annual carbon-dioxide emissions by as much as the output of the entire nation of Greece, news that Bloomberg’s climate reporters broke.

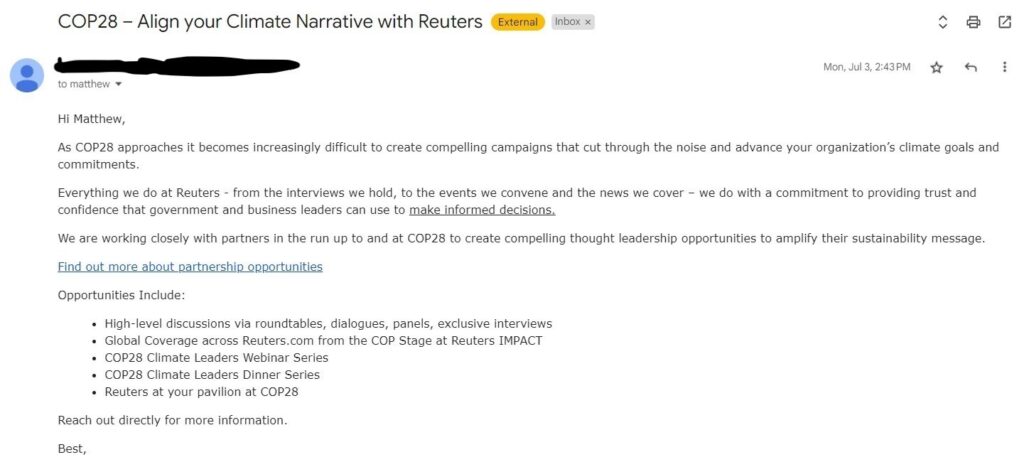

Meanwhile, Reuters Events has offered to help corporations hone their “climate narrative” at COP28, via opportunities to secure “exclusive interviews”; a place at high-level roundtables; coverage on the Reuters website; exclusive dinner invites, and a Reuters presence in corporate pavilions at the Dubai expo center hosting the negotiations. (Disclosure: Matthew Green has worked as climate reporter at Reuters).

“The considerations around what is the role of carbon-based industry in partnering with media organizations is not too dissimilar to the debates and discussions around what kind of role the carbon-based industry interests have in the climate talks themselves,” the IPCC’s Boykoff said.

‘Gross, Undermining and Dangerous‘

Reuters and other outlets whose in-house ad agencies are striking commercial deals with fossil fuel companies are trusted not only by the public, but by politicians and other key decision-makers. According to communications agency BCW’s annual survey of media brands in Europe, Politico, Reuters, the Financial Times and the Economist top the list of most influential media for EU decision-makers. All four are also some of the fossil fuel industry’s favorite partners for advertising and events.

And these partnerships haven’t just been happening in the leadup to COP28. Over the past three years, FT Commercial, the in-house ad studio of the Financial Times, has created dedicated web pages for fossil majors, including Equinor and Aramco, along with native content and videos, all of it focused on promoting oil and gas as a key component of the energy transition. An “FT Live” event focused on the energy transition featured speakers from BP, Chevron, Eni, and Essar.

The Economist’s in-house studio created a content hub around electrified transport for BP, which was also a platinum sponsor of its 2020 Sustainability Week event, while Petronas and Chevron sponsored the magazine’s “Future of Energy Week” event in 2022.

Politico runs a high volume of sponsored content for the fossil fuel industry. Over the past three years, the publication has run native ads more than 50 times for the American Petroleum Institute, the most powerful fossil fuel lobby in the U.S. Politico has also repeatedly run newsletters sponsored by BP and Chevron – the latter of which also sponsors its annual “Women Rule” summit – and run 37 email campaigns for ExxonMobil. Shell has sponsored every one of Politico’s “Energy Vision” summits since 2017.

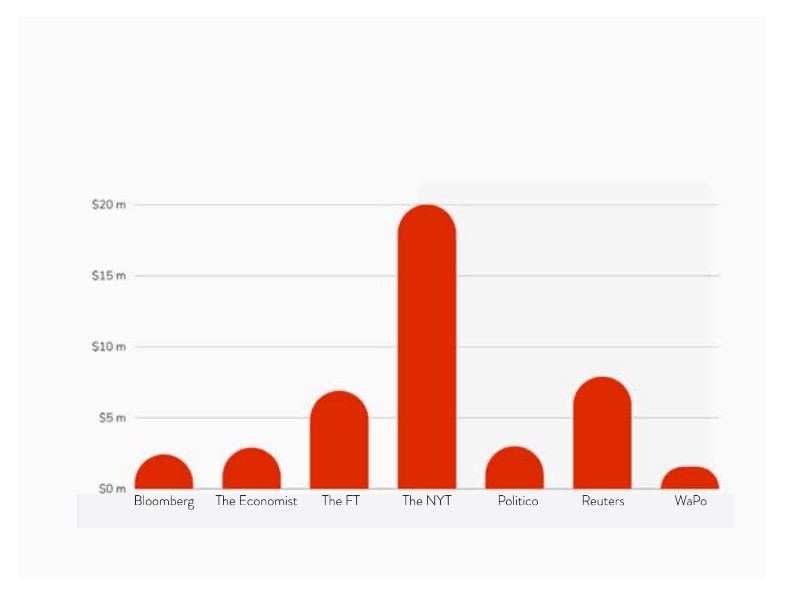

According to data from Media Radar, The New York Times took in more than $20 million in advertising revenue from fossil fuel companies from October 2020 to October 2023, twice what any other outlet earned from the industry. That number is due largely to the paper’s relationship with Saudi Aramco, which spent $13 million on ad space during this time period via a combination of print, mobile, and video ads as well as sponsored newsletters. That revenue does not include fees for creative services that were paid to the Times’ internal T Brand Studio. New York Times spokesperson Alexis Mortenson said that T Brand Studio does create custom content in print, video, and digital (including podcasts) for fossil fuel advertisers, and “we allow dark social posts if we’re creating this content.” “Dark social posts” are unpublished social posts promoted as ads to a specific audience, and do not appear on a brand’s timeline.

Regarding limits on these campaigns, Mortenson said, “We no longer allow organic social posts. Additionally, we allow fossil fuel advertisers to sponsor some newsletters. However, fossil fuel advertisers cannot sponsor any climate-related newsletter, such as Climate Forward and [climate journalist] David Wallace-Wells’ newsletter.”

Climate reporters at these outlets, who requested anonymity to avoid professional repercussions, alternately described their employers’ partnerships with oil and gas companies as “gross,” “undermining,” and “dangerous.”

“Not only does it undermine climate journalism, but it actually signals to readers that climate change is not a serious issue,” one climate reporter said.

Another journalist at a major media organization said the outlet had undermined its credibility by striking commercial deals with oil and gas companies that have long histories of hiring public relations agencies to cast doubt on climate science. “Where is our integrity? How can we expect people to take our climate coverage seriously after everything these oil companies have done to hide the truth?”

Harvard climate disinformation expert Naomi Oreskes agreed. “It’s really outrageous that outlets like the New York Times or Bloomberg or Reuters would lend their imprimatur to content that is misleading at best and in some cases outright false,” she said.

‘Vast Sums of Money‘

The fossil fuel industry’s practice of buying friendly content dates back to 1970, when Herb Schmertz, Mobil Oil’s vice president of public affairs, worked with The New York Times to create the advertorial. Mobil ran these pieces, which Schmertz described as “political pamphlets,” in the Times every week for decades. The rest of the industry quickly followed suit and the practice has continued ever since. A peer-reviewed 2017 study in the journal Environmental Research Letters of Mobil and then ExxonMobil’s New York Times advertorials found that 81 percent of those that mentioned climate change emphasized doubt in the science.

The past decade has seen these advertising programs super-charged by the advent of internal “brand studios” at most major media outlets: teams that are dedicated to creating content for advertisers, and market their ability to tailor that content to the outlet’s readership. These offerings come at a higher cost than traditional ad rates, making them increasingly important to newsrooms facing revenue meltdowns driven by the loss of classified and display advertising. And fossil fuel companies have been happy to pay.

“They wouldn’t be spending vast sums of money on these campaigns if they didn’t have a payoff and it’s well documented that for decades the fossil fuel industry has leveraged and weaponized and innovated the media technology of the day to its advantage,” said University of Miami professor Geoffrey Supran, who co-authored the 2017 advertorial study with Naomi Oreskes. “It’s sometimes treated as an historical phenomenon, but in reality we’re living today with the digital descendants of the editorial campaigns pioneered by the fossil fuel industry — the old strategy is very much alive and well.”

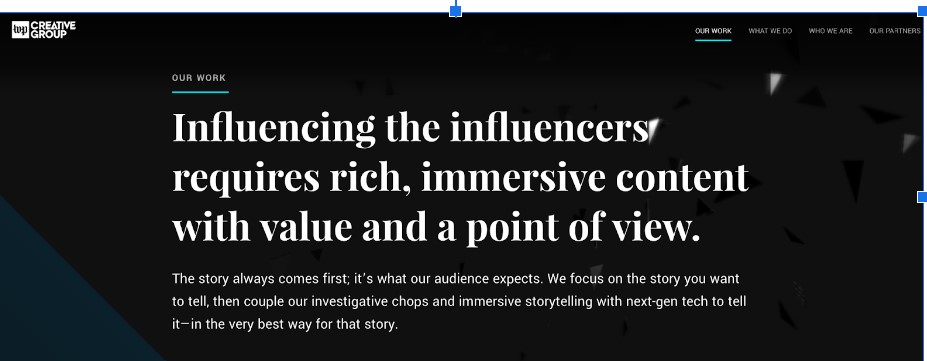

Taking a page from Schmertz’s book, The Washington Post Creative Group — the paper’s internal brand studio — describes on its website how it goes about “influencing the influencers.”

In 2022 alone, the group placed ExxonMobil sponsorships in more than 100 editions of Washington Post newsletters. Throughout 2020 and 2021, the Washington Post also ran a series of editorials for the American Petroleum Institute. These included a multimedia piece that highlighted fossil gas as a fundamental complement to renewable energy, and underscored talking points about the supposed unreliability of renewable energy sources — something that the paper’s reporters have often debunked. During these same years, The Washington Post published Pulitzer prize-winning climate reporting and expanded its climate coverage.

Reuters Tops the List

Of all the outlets we reviewed, only one company, Reuters, offers fossil-fuel advertisers every possible avenue to reach its audience, including custom events. It’s a notable shift for an outlet that has always counted “freedom from bias” as a core value — a pillar of the Trust Principles Reuters adopted to protect its independence during World War Two.

In 2019 Reuters News, a subsidiary of Canadian media conglomerate Thomson Reuters, acquired an events business. Since then, the distinction between the company’s newsroom and its commercial ventures has become increasingly blurred, with Reuters journalists routinely taking part as moderators and interviewers for Reuters Events, and proposing guest speakers.

For its “Hydrogen 2023” event, Reuters Events produced a companion whitepaper on the top 100 hydrogen innovators, designed to look very much like a product of the newsroom. This whitepaper was used to market the event in various other outlets, and topping the list of innovators were the key event sponsors, Chevron and Shell.

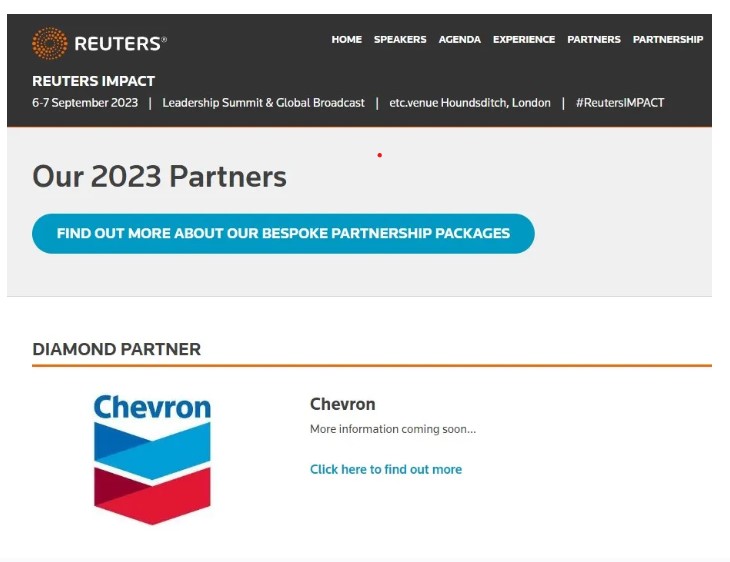

Reuters also partnered with Chevron, the “Diamond” sponsor of both its flagship “Reuters Impact” climate event in London in September 2023, and an upcoming “Global Energy Transition Summit” in New York in 2024. Reuters Events also stages fossil fuel industry trade shows explicitly aimed at maximizing production of oil and and gas, and creates digital events and webinars for vendors in the fossil-fuel supply chain looking to connect with oil and gas companies. In a media kit for “content opportunities in the upstream industry,” Reuters Events offers to produce webinars, white papers and live event interviews for those hoping to get in front of its “unrivalled audience reach of decision makers in the oil & gas industry.”

In June 2023, Reuters Events convened hundreds of oil, gas and tech executives in Houston for “Reuters Events Data Driven Oil & Gas USA 2023,” a conference held under the banner “Scaling Digital to Maximize Profit.”

“Time is money, which is why our agenda gets straight to key pain points holding back drilling and production maximization,” the conference website said.

Six months earlier, in December 2022, Reuters Events had run an event sponsored by the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, an industry lobby grouping many of the world’s largest oil companies, to discuss the “major part” fossil-fuel companies “play in ensuring a sustainable energy transition,” and tweeted industry talking points from the Reuters Events twitter account.

For the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative, the only real KPI is how much greenhouse gas is being removed from the oil and gas industry's output every year.#ReutersIMPACT

— Reuters Events (@reutersevents) October 28, 2022

Watch the full session, brought to you by @OGCInews: https://t.co/QlXUlaAXFm pic.twitter.com/I159E923NF

Reuters’ creative studio Reuters Plus has produced content for multiple oil majors including Shell, Saudi Aramco, and BP that ranges from native print, audio and video content to white papers.

A Reuters spokesperson said its Reuters Plus studio allowed companies to connect with audiences attending Reuters Events via clearly labelled sponsored content.

“Reuters Events serves multiple professional audiences involved in the most important discussions of our day; facilitating these discussions is an important part of the Reuters Events business,” the spokesperson said.

“Business-to-business publishers always had an events revenue stream, but consumer-facing news publications didn’t really get into the events business until digital advertising became commodified,” said media analyst Ken Doctor.

Events — which now represent 20 to 30 percent of revenue for some publications — are appealing for advertisers, too. “It’s a thought leader exercise,” Doctor said. “There are only a few top media brands out there and if you are associated with any of them, there is a lot of tangential brand building benefit to that.”

The additional revenue may come at a reputational cost for news outlets, though. According to Oreskes, events run by media organizations that explicitly endorse the fossil fuel industry’s agenda pose even greater conflicts of interest than advertorials running alongside climate news coverage. “It really crosses the line because now they’re actually manufacturing content,” she said. “They’re manufacturing content that at best is completely one-sided and at worst is disinformation, and pushing that to their readers.”

After seeing the scope of Reuters’ involvement with the fossil fuel industry, we wondered how a media organization that’s curating industry events aimed at accelerating oil and gas development could qualify for membership in Covering Climate Now, a nonprofit organization that offers newsrooms the opportunity to “demonstrate leadership among their peers — and to show readers, listeners and viewers that they’re committed to telling the climate story with the rigor, focus, and urgency it deserves.” (Disclosure: Amy Westervelt is on the steering committee for Covering Climate Now, of which both DeSmog and Drilled are members).

In a written statement, Mark Hertsgaard, the executive director of Covering Climate Now, said that “Covering Climate Now has had no communication with Reuters about any activities backing faster development of fossil fuels.” Hertsgaard added that “Covering Climate Now has always taken a big-tent approach to our partnership with news organizations. This story raises serious questions about news media responsibility in climate reporting, and Covering Climate Now plans to think more deeply about these questions and how we might adjust our policies going forward.”

‘PR Campaigns‘

Even as their content marketing about the journey to net zero continues to get bigger and better, oil majors’ investments in fossil fuel development have only increased. A peer-reviewed study comparing oil majors’ advertising claims and actions, published in the journal Plos One in 2022, found that while the companies are talking more than ever about energy transition and decarbonization, they are not actually investing in either. The study’s authors wrote that “the companies are pledging a transition to clean energy and setting targets more than they are making concrete actions.”

This disconnect between advertising and action is something the media should be covering more, according to Brown University environmental sociologist Robert Brulle. “Good, critical reporting would have to challenge the statements of these fossil fuel companies,” he said.

Reporters at Reuters, The Washington Post, The New York Times, the Financial Times, Politico, and Bloomberg do exactly that. Then some of their employers undermine that critical reporting by selling the space right next to those stories for industry-sponsored takes.

“I feel like it’s really important not to beat around the bush and to just recognize these activities for what they are, which is literally Big Oil and mainstream media collaborating in PR campaigns for the industry,” Supran said. “It’s nothing short of that.”

Read the Drilled-DeSmog report Readers For Sale: The Media’s Role in Climate Delay.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts