Players in the carbon dioxide pipeline industry canceled major pipeline projects in recent weeks, marking an inauspicious start to President Biden’s ambitious plans to develop carbon capture infrastructure as a key emissions mitigation tool.

It is welcome news to CO2 pipeline opponents, however, which have included a wide spectrum of interest groups united in their concerns over pipeline safety.

“I think what the cancellation shows is that people have had enough of fossil fuel infrastructure being forced upon them,” said Lorne Stockman, research co-director with Oil Change International. “It doesn’t surprise me that communities are standing up to these projects and occasionally winning.”

Stockman pointed out that the U.S. oil and gas industry has built millions of miles of pipelines, and hundreds of thousands of miles were installed in the last decade and a half as a result of the fracking boom. “There is a general awareness that the age of fossil fuels needs to end and that we need to transition to genuinely clean energy, and not dangerous distractions like carbon capture,” he added.

Navigator CO2 Ventures ended their “Heartland Greenway” carbon dioxide pipeline project on October 20, citing “the unpredictable nature of the regulatory and government processes involved.” The project aimed to capture 15 million metric tons of carbon dioxide from ethanol plants in the U.S. Midwest to be injected and stored underground. Much like the fossil fuel industry — which seeks to use carbon capture and storage (CCS) because they allege it will assist in decarbonizing continued oil production — carbon capture is the primary emissions mitigation tool preferred by the ethanol industry as well.

However, experts point to significant problems with the CCS process, particularly that it has historically been used primarily to pump more oil out of the earth. Burning that oil emits much more CO2 than what is captured, which means the technology wouldn’t represent a feasible solution to address climate change.

Both local and national reporting indicate that the Navigator pipeline proposal attracted the attention of diverse groups of citizens often portrayed as being on opposite ends of the political spectrum. Yet they stood undivided in voicing shared concerns over pipeline safety and possible expropriations via eminent domain.

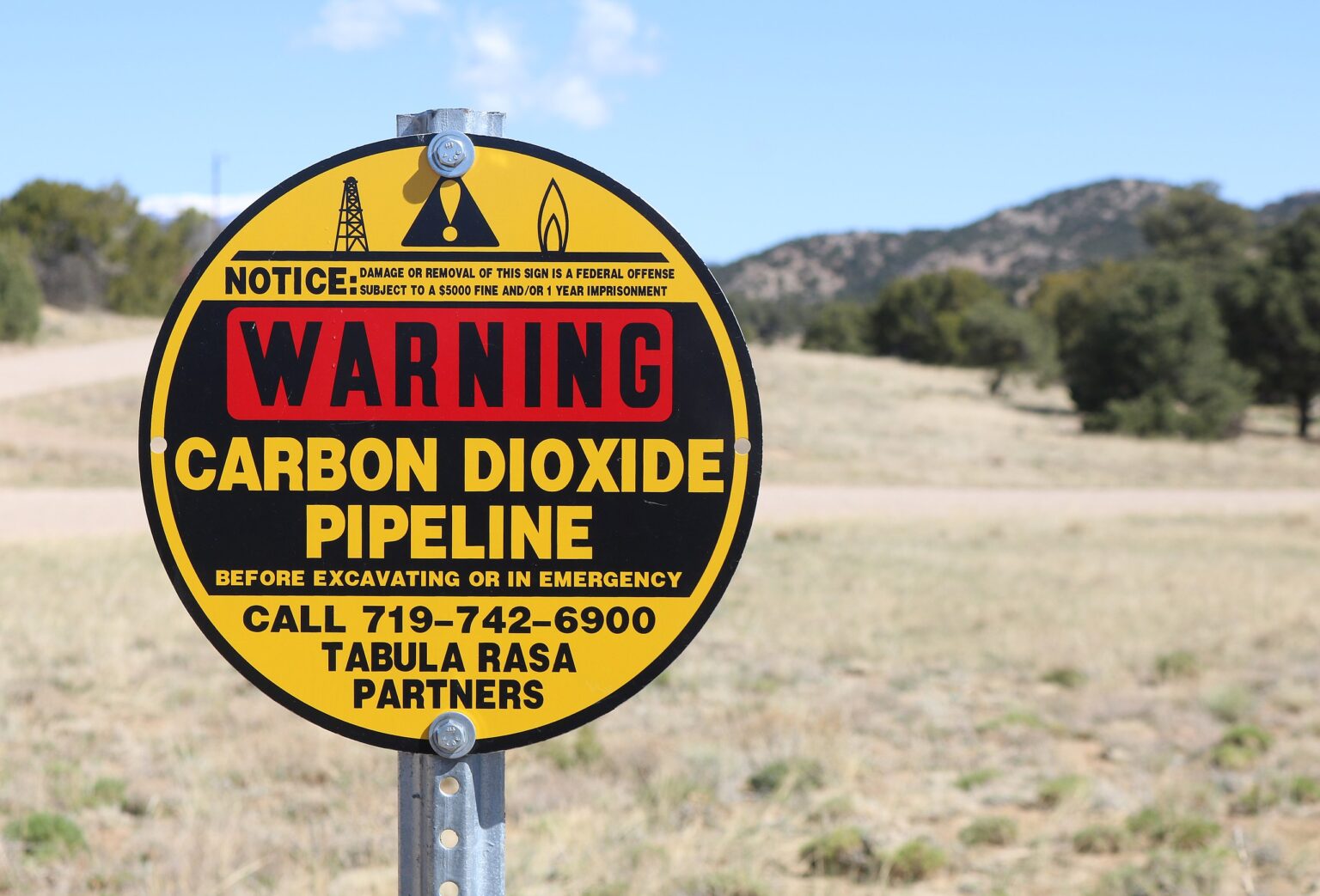

Navigator’s $3.5 billion Heartland Greenway project called for 1,300 miles of pipeline across five states, with carbon dioxide storage to have taken place in Illinois. Residents in that state were resolutely opposed to the project, largely because of fears related to a pipeline rupture, like the one in Satartia, Mississippi, in February 2020. Nearly 50 people were hospitalized in that disaster, and continue to suffer from adverse health effects.

The disaster also forced the evacuation of 300 people, after the rupture spewed the odorless, colorless gas into the air for several hours. Carbon dioxide is an asphyxiant, and CO2 poisoning can leave victims disoriented and appearing to be drugged. Left untreated it can eventually lead to cardiac and pulmonary problems. More problematic is the relative rarity of mass CO2 poisoning events, meaning first responders might be unfamiliar with how to treat the symptoms. In addition, first responders — such as those responding to the disaster in Satartia — could be hampered by the engines of their vehicles shutting off in the oxygen deprived environment.

These critical health, safety, and disaster-response issues notwithstanding, it was regulatory and bureaucratic processes that have so far stymied carbon dioxide pipeline and capture projects in the Midwest.

South Dakota regulators denied Navigator’s application to build a section of the pipeline in that state in September.

The CCS company’s decision to cancel the project is significant for several reasons.

First, Navigator sought to use eminent domain to force landowners to give up their property, and was unsuccessful. Had these been oil or gas pipelines, the landowners might not have been as successful, because fossil fuel pipelines have generally been considered so fundamentally important to the public good that oil and gas companies can get around the Public Use Clause in the U.S. Constitution’s Fifth Amendment.

The company also has some serious financial backers, including Texas-based oil refiner Valero Energy Corp., and the world’s largest asset management company, BlackRock.

Iowa-based Summit Carbon Solutions is also proposing the Midwest Carbon Express, a $5.5 billion, 2,000-mile pipeline network across five states, to sequester carbon dioxide emissions from 34 ethanol plants. The CO2 was to be stored in North Dakota, but state regulators denied Summit Carbon a siting permit in August. Then the South Dakota Public Utilities Commission voted unanimously to strike down the company’s application to build a section of the pipeline network through that state as well. Though other pipeline projects have faced stiff public opposition, authorities denied the application to build this pipeline segment because it would violate county ordinances relating to setbacks and other aspects of the pipeline’s route. Summit has accepted the decision and indicated it would “refine their proposal and refile” for the necessary permits.

The Biden administration promised $251 million for CCS projects in seven states in May, from an estimated $12 billion fund from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law for carbon management in the United States. Reporting from the Associated Press indicated that the funding announcement was a vote of confidence for what is expected to be a largely industry-driven initiative. The same article revealed that most of the funds have been dedicated to nine existing carbon capture projects, with an aim to sequester 50 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. Though this may seem impressive at first glance, it’s negligible when compared with the 5.5 to 6.3 billion metric tons of CO2 emitted annually in the United States alone. It’s especially insignificant given that most, if not all, of these projects are used for enhanced oil recovery — the injection of carbon dioxide into wells to extract the last remaining amounts of oil for production.

“Instead of incentivizing a CO2 reduction, the Inflation Reduction Act, along with the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, through their funding of carbon capture, actually incentivize net increases in CO2, air pollution, land use and consumer costs,” said Mark Z. Jacobson, in an editorial published by The Messenger. Jacobson is a professor of civil and environmental engineering and director of Stanford University’s Atmosphere/Energy Program.

Jacobson identified the Summit project as one that is a direct beneficiary of Biden administration incentives for carbon capture. Noting that no study had determined whether this was an effective or efficient use of public money, Jacobson conducted a study to find out, which was recently published in Environmental Science and Technology. Jacobson compared the anticipated emissions savings and cost of the Summit project, which was intended to provide decarbonized ethanol for use in flex-fuel vehicles, with spending an equal amount on wind farms. The comparison also used two 2023 Ford F-150 pickup trucks for the modeling, as the F-150 is available in both electric and flex-fuel powered variants.

The results were impressive: Compared with the flex fuel-powered F-150, the fully electric version, powered by renewable wind energy, reduced CO2 emissions by 2.4 to four times, and could save drivers tens of billions of dollars – even accounting for the higher cost of the electrically powered F-150. Using wind power would also use 1/400,000 of the land footprint, and would lower air pollution levels, too.

Not only is this better for consumers, the wind and electric vehicle model virtually eliminates CO2 emissions, negating any need for carbon capture, while the ethanol and flex fuel model, even with carbon capture, would still result in a net CO2 increase.

Watchdogs argue carbon capture is being presented to the public as part of the government’s decarbonization efforts, despite being consistently proven to be incapable of reducing CO2 at the scope and scale necessary for climate change mitigation.

“Carbon capture started as a means to enhance oil production,” said Stockman. “It was not developed to address climate change.”

He pointed out that CO2 must be separated from methane in gas processing plants to meet market requirements for gas, and in most cases, it is vented into the atmosphere. In 1972, a plant at the Sharon Ridge oilfield in Texas was designed to capture CO2 from a particularly CO2-rich source of gas. Engineers wanted to see if pumping it into declining oil wells would help squeeze more oil out and make more money, Stockman said. “It worked, and that has been the model for CCS ever since.”

Stockman said that most attempts to use carbon capture and storage to reduce emissions from power plants have failed or been found to be too costly to pursue.

“The most notable success that CCS can claim is how successfully it has been used to convince politicians that it will one day be able to reduce emissions and, therefore, should be supported with public money,” he noted.

“It’s been very successful in capturing public money, which is a testimony to the long history of ‘state capture’ that the oil and gas industry has enjoyed in the U.S.,” he added, referring to Big Oil’s pressure on governments to secure public funding for their projects.

“Large budgets for lobbying and campaign finance have helped the industry maintain subsidies and tax credits, some of which have been around for many decades,” Stockman said. “The 45Q tax credit for carbon capture and EOR [enhanced oil recovery] is just the latest in this long history.”

The ethanol industry is expecting demand to decline in coming years, as recently reported by S&P Commodity Insights. Producing ethanol with CCS would meet some government and industry standards for lowering carbon intensity fuels.

However, experts and analysts routinely point out the capturing and transport process is itself carbon intensive, to the point of negating whatever positive effects sequestration might provide. Jurisdictions like California, Washington state, and the Canadian province of British Columbia could still be viable markets for low carbon intensity ethanol. There is also the possibility of using ethanol as a sustainable aviation fuel, but it all hinges on developing the infrastructure to sequester the carbon dioxide emitted during production.

Even if current pipeline projects have been canceled or shelved, there’s still considerable industry interest and incentive in finding a way to make the projects work.

Stockman urges caution before activists take a victory lap.

“I think folks need to be aware that while they have succeeded in the Midwest, communities in Texas and Louisiana are facing an overwhelming surge in gas, LNG, and CO2 infrastructure,” he said. “Both states have very oppressive legislation in place against protest and opposition to fossil fuel infrastructure, and these communities need our support, as their fight is much harder.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts