The plastics and petrochemical industries’ latest purported solution to the plastic pollution crisis – chemical or “advanced” recycling – is essentially a public relations and marketing strategy designed to distract from the urgent need to curb plastic production, a new report contends. The report, released today by Beyond Plastics and the International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN), exposes the failures and perils of chemical recycling as an approach to manage plastic waste.

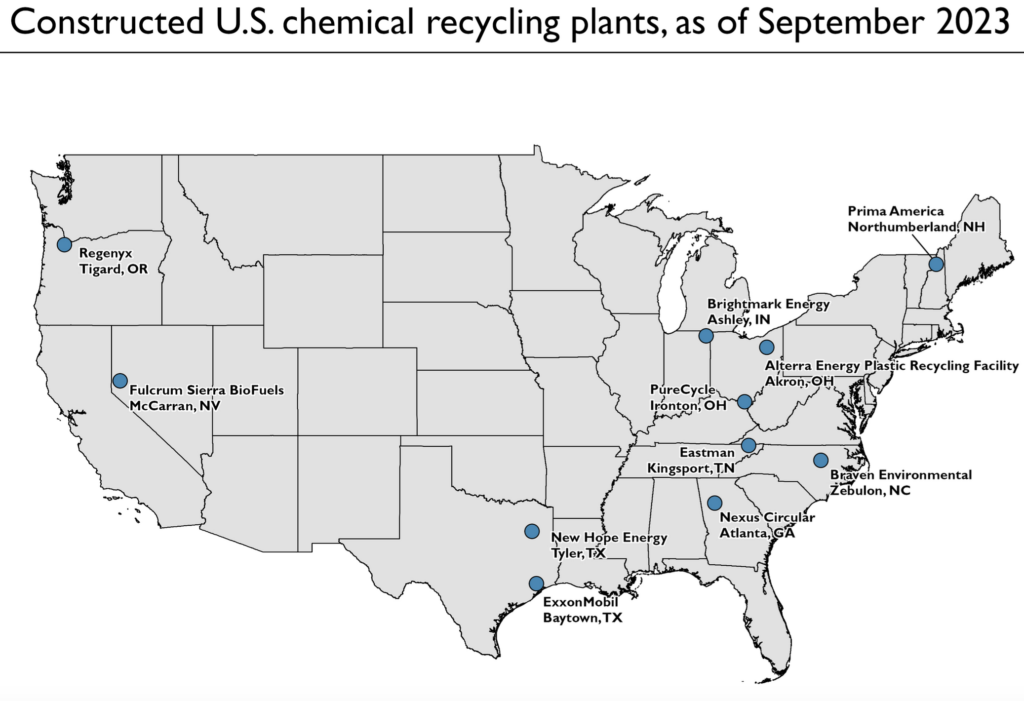

Only 11 chemical recycling facilities currently exist in the United States, and in total they are capable of processing less than 1.3 percent of all plastic waste generated annually, the report finds. The facilities do not operate at full capacity most of the time, however. Pervasive underperformance, hazardous working conditions, perpetuation of environmental racism, and financing challenges are among the many issues plaguing these operations, according to the report.

“I think the [plastics] industry is relying on confusing people, starting with what is it, and what do you call it,” Judith Enck, president of Beyond Plastics and a former EPA regional administrator, told DeSmog.

There is no legal definition of chemical recycling. The term generally describes industrial technologies that chemically process plastic waste, melting or boiling it down into gasses, chemicals, or fuels. The process is extremely energy intensive and inevitably generates toxic byproducts. While industry associations like the American Chemistry Council and America’s Plastic Makers now refer to it as “advanced recycling,” Enck said it is neither advanced nor recycling. “What we’re finding is very little new plastic is actually created,” she said.

Instead, many of the technologies use methods like gasification and pyrolysis to convert plastic into fuel. Pyrolysis is the process of heating a certain substance without oxygen, in this case to chemically break down plastics into their component parts so they can be made into other chemical substances or into fuels. Such a conversion is not recycling, according to internationally accepted definitions, the report notes.

Chemical recycling itself is not new. “The industry has been at this for decades,” Enck said. Disney World, for example, built a pyrolysis facility in 1982 to help address its plastic waste problem. The facility closed shortly thereafter because it was too expensive and inefficient to operate, requiring twice as much energy as Disney had originally projected.

In addition to its longstanding failures, chemical recycling contributes to toxic air pollution, hazardous waste buildup, and climate change, all while threatening communities experiencing environmental injustice, the report finds.

“The landscape of chemical recycling in the United States is littered with failure and pollution,” Beyond Plastics deputy director and report contributor Jennifer Congdon said in a press release. “Several of the U.S. facilities are registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency as large generators of hazardous waste, and the majority are located in communities of color, low-income communities, or both.”

The report calls for a nationwide moratorium on all new chemical recycling facilities. It also urges much stricter regulation and scrutiny of these operations, including prohibiting their siting in environmental justice communities and ending government incentives for these facilities at all levels, among other recommendations.

Under heavy lobbying pressure from the plastics and petrochemical industries, however, states are enacting laws to deregulate chemical recycling. Enck said 24 states have so far adopted policies promoting chemical recycling that classify it as manufacturing, which makes the operations eligible for even more generous subsidies while allowing them to be built under more lax environmental regulations.

At the international level, delegates are preparing to convene for the next round of negotiations for the drafting of the UN plastics treaty, to be held November 13 to 19 in Nairobi, Kenya. The plastics industry is “pushing hard” to have chemical recycling included in the treaty, Enck said, though so far it has failed to convince delegates to adopt the strategy.

Plastics Industry “Knew” Recycling Was a Lie

In the report’s forward, a former high-ranking official for the plastics industry recalls the internal conversations that prompted “aggressive advertising campaigns” to promote recycling. Lewis Freeman, who served as vice president of government affairs at the Society of the Plastics Industry (now called the Plastics Industry Association) from 1979 to 2001, reveals that industry executives insisted the lobby group “advertise its way out of plastic’s growing public relations problem” as public concerns grew around the material’s environmental impacts.

“Despite knowing that plastics recycling couldn’t realistically manage a significant amount of plastic waste, companies spent millions of dollars convincing the public otherwise,” Freeman writes. He emphasizes that plastic pollution “is a waste problem for which recycling is not a suitable response.”

The industry “knew plastic recycling was never going to work,” Enck told DeSmog. “They knew it was a lie.” Enck said she has noticed “a real uptick” in recent months in plastics industry advertising in major media outlets.

“It’s really more of a lobbying and marketing campaign,” she said, “than an actual solution to the plastic pollution problem.”

Chemical recycling is a “false solution” to the plastic pollution problem, the report argues, and it has striking similarities to carbon capture and storage (CCS) – technologies that aim to manage carbon pollution from emitting facilities. CCS critics say it is a false solution to the climate crisis, noting it has a track record of underperformance and failures, is inefficient, energy intensive and expensive, and threatens environmental justice communities. The fossil fuel industry is among the biggest backers of CCS, just as the plastics industry is the biggest promoter of chemical recycling.

“There are scary parallels between what the fossil fuel companies are saying about carbon capture and storage and what the plastics/fossil fuel/chemical companies are saying about chemical recycling,” Judith Enck, president of Beyond Plastics and a former EPA regional administrator, told DeSmog. “They must all use the same PR firms, and the question is, will policymakers fall for it?”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts