Plaquemines Parish residents Mark and Barb Comeaux take little comfort in NOAA’s predictions of a near-normal Atlantic hurricane season this year. They live in Plaquemines Parish a few hundred feet from a massive liquified natural gas (LNG) export terminal being built by Venture Global and the Gator Express pipeline, which will transport natural gas under high pressure to the facility.

“There is only one road leading in and out so if there is a problem at the facility or with the pipeline we will be stuck,” Mark told me on May 25 while we watched pipeline being built in wetlands from the deck of his brother’s porch, located across a small bayou from his home.

The plant’s main entrance is on Highway 23 in Port Sulphur, 20 miles south of New Orleans, Louisiana. Until construction began, it was a quiet, open road, next to a sparsely populated rural community that is known as a great place to fish. Now it is often backed up with traffic around the facility. The highway traverses the state’s southernmost parish, which is divided by the tail end of Mississippi River that empties into the Gulf of Mexico. Highway 23, which is on the west bank of the river, leads to the tip of a 70-mile peninsula and is prone to flooding, as is Hermitage Road, a small road, off the Highway that leads to the Comeauxs’ home and the back of Venture Global’s site. Residents who do not evacuate when hurricanes threaten the area risk being stuck until floodwater recedes.

In Plaquemines Parish, like much of the southern part of the state, elevation averages about 3 feet above sea level. An increasing number of strong hurricanes hitting the coast’s rapidly eroding wetlands and barrier islands, which provide natural storm surge protection, make the parish increasingly vulnerable to climate impacts.

The rapid intensification of recent hurricanes that hit Louisiana’s coast—Hurricane Laura in 2020 and Ida in 2021—have complicated storm preparations and evacuations from coastal communities. With few roads leading out of the region, last-minute evacuations have led to massive traffic jams. Some who are unable to leave on their own but who would evacuate if they could, have been left in harm’s way. It’s complicated for local governments, like the city of New Orleans, to organize safe passage for residents if an evacuation is called for on short notice—and in the case of Ida was ruled out. Though the storm didn’t devastate the city, 11 of the deaths attributed to Ida were residents who remained in the city and had no way out after power failed. Many were without power for over a week.

Despite climate scientists warning of the need to curtail the use of fossil fuels to prevent global temperatures hitting a tipping point, several other proposed LNG export facilities along Louisiana’s coast might soon join the three facilities in the state’s southwest and Venture Global’s Plaquemines Parish site. And now measures included in the Fiscal Responsibility Act, a law passed to lift the debt ceiling, make it possible to shave years off the permitting process.

The Comeauxs aren’t the only ones unnerved about what might happen when a hurricane hits the new LNG facility in their backyard. Kindra Arnesen, a shrimper who lives in Buras, a small town close to the tip of the parish, fears that all points south of the new facility will be inaccessible after any sizable storm. She became an advocate for her community following BP’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, and continues to fight for their rights.

“The company took away our road home,” Arnesen told me recently. When Highway 23 is flooded, she and others living south of the facility have used a dirt road on top of the Mississippi River Levy, open for limited use only, as an evacuation route. But it is now blocked by a hydraulic ramp that goes from Venture Global’s Plaquemines Parish site directly to the river.

Though the ramp can be raised if it has a power source, she isn’t sure who decides when it will be lifted, or what measures are in place to ensure it can remain operational if a major storm hits.

She told me that she and others in her community likely will not evacuate because they can’t afford to risk not being able to quickly return to secure their homes and fishing vessels once a storm passes. It can take days before floodwaters on Highway 23 go down, so without being able to drive along the top of the levy to get home many will choose to risk their lives rather than leave their homes unprotected.

Though a parish official assured her the company will raise the ramp in case of an emergency, Arnesen has yet to be shown a contingency plan for evacuating residents south of the facility during any potential disaster, despite requesting one. I inquired with Venture Global and the Parish about contingency plans related to the ramp, but did not receive any specifics.

Venture Global stated via email that it plans to raise the ramp if need be and that it has a separate power source for it. Neither the company or the Parish would say if the public was privy to any contingency plan they have. Nor would either party say who decides when the ramp is lifted, although the Parish implied it was the company by referring me to Venture Global for answers.

Arneson finds it worrisome that it is unclear whether or not the government controls infrastructure built by a private company that blocks the levy. It doesn’t sit well with her that her community’s ability to get home if the highway is flooded might be decided by the company now. She is also troubled that she can’t get her hands on a contingency plan to evacuate in the case of an extreme weather event or a disaster at the LNG plant, making her doubt one exists.

If a storm doesn’t total your home, letting it sit unprotecting after one can, she explained. Any water that gets in will cause mold to spread rapidly. If you have insurance and do not secure damage after a storm, it can void your coverage; those who are not insured or are underinsured can’t rebuild with only the funds available via FEMA, so it is critical to patch holes in roofs to prevent additional water damage or strip out wet flooring, drywall, and belongings as soon as possible.

The risks have not only been recognized by the state’s home insurance industry, which is facing collapse despite the skyrocketing rates being paid by its customers, but also by Ivor van Heerden, a scientist known for predicting the collapse of New Orleans’ levies before Katrina hit, who is now a consultant specializing in environmental and coastal issues.

“A major storm surge from a hurricane hitting a facility like Venture Global’s Plaquemines Parish LNG export facility is a catastrophe waiting to happen,” van Heerden said during a May 17 press conference held by the Louisiana Bucket Brigade, an environmental advocacy group that is pushing back against the expansion of fossil fuel projects in the state.

Last year van Heerden filed an affidavit that alleges design flaws in Venture Global’s Plaquemines Parish project’s proposed storm wall that could lead to a levee failure. He wrote it on behalf of three other Louisiana-based environmental groups—Healthy Gulf, the Sierra Club, and the Deep South Center for Environmental Justice—that jointly filled a lawsuit against the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources for exempting Venture Global from needing a coastal use permit in Plaquemines Parish.

The May 17 press conference was held to raise alarm over annual air monitoring reports Venture Global released that indicate numerous permit violations at its Calcasieu Pass LNG export terminal in Cameron Parish, located on the Gulf Coast in the state’s southwest. In a letter to regulators, the Bucket Brigade lambasted the company for seeking permission to pollute more by increasing emission limits in its air quality permit, rather than fixing the issues that led it exceed its permitted emissions. The letter points out that the three additional export facilities the company plans to build in Louisiana, including the facility under construction in Plaquemines Parish, are based on the same flawed design.

Despite the climate crisis, for many state leaders LNG export facilities and petrochemical projects can’t be pushed through the permitting process fast enough. During a press conference over Memorial Day weekend, Rep. Garret Graves (R-LA), credited with leading GOP negotiations on the debt ceiling bill, hailed the inclusion in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of measures to streamline the permitting process for energy projects as a major victory for the Republican Party. Graves’ previous attempts to “modernize” the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in the name of energy security had been rebuffed until now.

“Any changes to NEPA that fast-track the permitting process will likely lead to bad environmental and health impacts,” Wilma Subra, a technical advisor who works with frontline communities, said on a call after the bill passed. She pointed out that these changes threaten to leave even more stakeholders out of the permitting process.

Even without streamlining the permitting process, Subra and other environmental advocates do not think the public is given enough time to review the permit applications. At best, they have only a few weeks to review lengthy technical applications before the comment period closes. Flaws she and others have identified in recent applications in the state are at the heart of legal challenges that can lead to permits being made more protective, applicants withdrawing applications, and in some cases permits being revoked.

Subra questioned the speed at which the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality (LDEQ), one of the permitting agencies, was moving last year at a permit hearing for a proposed export facility by Commonwealth LNG. The Texas-based company had proposed a terminal across from Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass LNG facility, and Subra pointed out that LDEQ issued an administrative completeness letter to Commonwealth LNG the same day it received its 850-page application. She expressed doubt that it was possible to do such a review in one day.

Now, thanks to Graves, proposed projects related to the Biden administration’s push to expand the hydrogen fuel market and carbon capture and sequestration (CCS) hubs could be realized at a much fast pace, despite growing opposition to them. Though the fossil fuel industry and the administration describe these projects as part of a climate solution, hydrogen fuel production will increase climate warming emissions and CCS projects may not be as safe or effective as described.

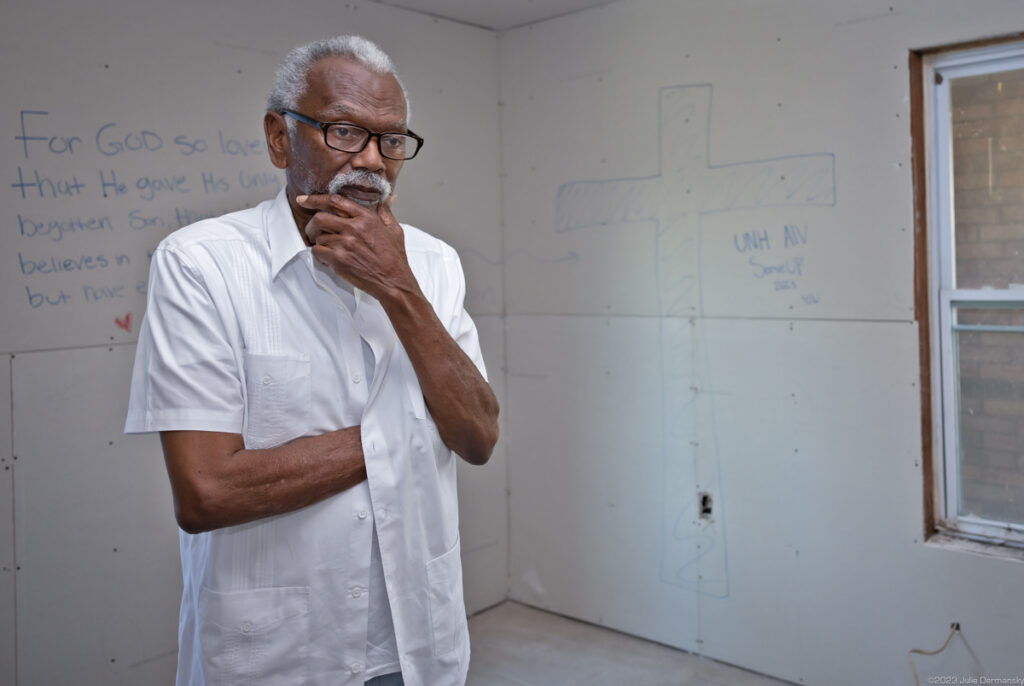

St. John the Baptist Parish resident Robert Taylor—a leader in a fight for clean air in Cancer Alley—is part of a growing coalition opposed to a hydrogen and ammonia manufacturing complex and CCS hub currently being developed by Air Products, a global hydrogen producer. He is still dealing with impacts from Hurricane Ida; the storm nearly destroyed his home, and it remains uninhabitable. He was unaware of the company’s plans to build a manufacturing complex in Caner Alley, about 40 miles northwest of the Lake Maurepas and a CCS hub under the lake until after the state leased the land under it to the company.

Taylor is glad that his local government leaders joined those of Livingston and Tangipahoa parishes, which also share the banks of the lake with St. John the Baptist Parish, in trying to slow down the permitting process for Air Products’ project. Residents in those parishes, also impacted by Ida, spearheaded the fight against the company’s CCS hub, which, if realized, will release globe-warming methane and put the region’s drinking water at risk. However, efforts to pass bills with measures to slow down the company’s project failed during the current legislative session.

Travis Dardar, an Indigenous fisherman in Cameron, Louisiana, and his wife Nicole have a front-row view of the rapidly expanding LNG export industry. They live a few hundred feet from Venture Global’s Calcasieu Pass LNG terminal and less than a one hundred feet from the site where the company plans to build a second facility. Like the Comeauxs, they are frustrated that the government does not mandate companies to offer an equitable buyout package to residents whose health, safety, and livelihoods are threatened by projects it permits. Though the Dardars are relocating after working out a deal to sell their property to the company, the stress of living so close to the facility—from the constant noise, pollution, and threat of a potential catastrophic accident—took a toll on them.

The Dardars assert that even though the permitting agencies and companies followed the rules required for posting notifications about how and when the public could comment on the permits, their community was unaware of the notifications, so they and their neighbors didn’t weigh in. Similarly, community members around Lake Maurepas missed notices giving them a chance to comment on the operating agreement that the state gave Air Products, leasing the company the right to utilize the bottom of the lake, because they were made when many were without power following Hurricane Ida.

Back-to-back industrial incidents on June 5, attributed to lightning strikes, proved to the Dardars how much riskier staying in the area during hurricane season could be. A tank containing the toxic chemical naphtha caught on fire at Calcasieu Refining in Lake Charles, leading to an evacuation for those within 1.5 miles of the facility. An LNG tank at a power station in Cameron also ruptured and burned for hours, resulting in the Dardars needing to evacuate their home and leaving their neighborhood without power for several days.

“[Rep.] Graves’ claim that streamlining the permitting process of energy projects will help secure our energy independence is proof that our politicians are bought and paid for by the oil and gas industry,” Dardar told me recently when I met him on the Isle de Jean Charles, a barrier island that is now mostly uninhabited following the first federally funded relocation project related to climate change.

“The real issue our politicians need to deal with is our food security,” he said. He is aware that climate change is already impacting the seafood industry, which the buildout of the LNG industry along with the hydrogen market and CCS projects further jeopardizes. He believes that exporting large quantities of LNG will reduce the availability of natural gas at home and that building facilities on the coast heightens the safety risk to fenceline communities during hurricane season. If Venture Global’s LNG Calcasieu Pass Terminal takes a direct hit from a powerful storm, he believes it would not only have the potential to wipe out the whole town but also to impact the global energy sector that is increasingly reliant on LNG.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts