For the fifth time, a Louisiana lawmaker has introduced legislation to try to reduce the tax that fossil fuel firms pay on oil they produce in the state. The original version of the bill introduced by Rep. Phillip DeVillier this spring would have cost the state $97 million over the next five years, according to a Louisiana Legislative Fiscal Office report.

“It’s just so much money,” said Rep. Mandie Landry, who voted against the bill in the House Committee on Ways and Means and again when it was before the full House. After it passed the House, the Senate Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Committee was scheduled to vote on the bill on May 22, but Rep. DeVillier voluntarily postponed the vote. DeVillier, who received more than $5,700 in donations from oil and gas interests last year, brought similar legislation four times between 2020 and 2022.

The latest bill, HB 172, would reduce the severance tax rate on oil from certain wells from 12.5 percent to 8.5 percent in one-half percent increments over seven years. Rep. DeVillier did not respond to requests for comment for this story. But at the House Ways and Means committee hearing in April, he said the legislation would bring more oil drilling because it would make Louisiana more competitive with the tax rates of other states. “I believe by lowering the rates we’re going to attract more businesses to come and produce oil here in Louisiana,” he said, adding that the increased production would bring more jobs.

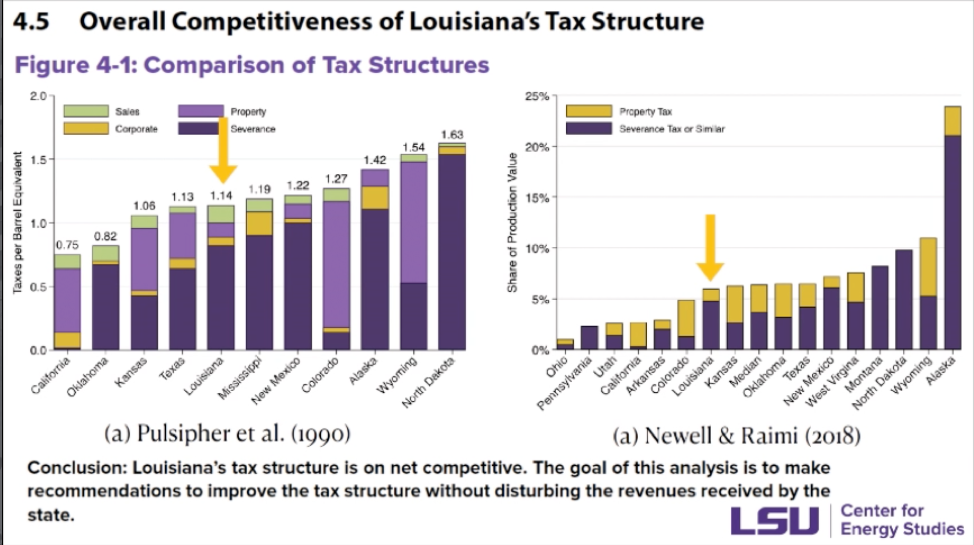

While other states have lower severance tax rates for oil — Texas taxes oil at 4.6 percent — Louisiana charges companies less in property taxes and has lower corporate taxes. The state also has a generous tax exemption on horizontal drilling, allowing companies to avoid paying severance taxes on production for the first two years after the well is drilled. That tax exemption has allowed fossil fuel firms to dodge more taxes on natural gas than they pay in the state, according to an analysis by Louisiana State University Center for Energy Studies. The state ranks third in the nation for producing natural gas and tenth for crude oil.

This year, Louisiana lawmakers have been trying to work out what to do with a budget surplus. But a financial cliff could be around the corner, in part due to a state sales tax scheduled to end in mid-2025, according to the Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana. The general fund, where state mineral revenue is directed, is used for higher education, health services, and public safety programs.

“At the end of the day, HB172 is an unnecessary and substantial transfer of wealth to a more-profitable-than-ever oil and gas industry at the expense of the state and our communities being considered as the state hurtles towards a fiscal cliff,” said Jackson Voss, the climate policy coordinator for the Alliance for Affordable Energy. “Passing it would be deeply irresponsible.”

Analyses by the legislative auditor and Greg Upton, the interim executive director for the Louisiana State University Center for Energy Studies, found that projected increases in oil production stemming from the bill could not override the revenue losses the bill would have on the state and local governments. “In terms of the fiscal impact, I certainly think, and we did analysis on this, the amount of new activity is not going to be large enough to make the fiscal note zero,” Upton said at the committee hearing in April.

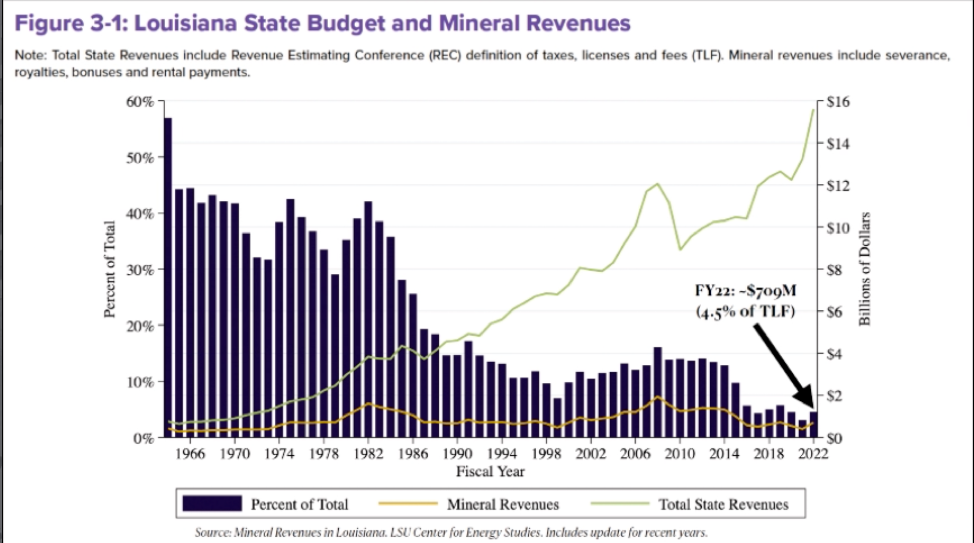

Landry too has doubts that lowering the oil severance tax would jump-start the oil and gas industry in the state again. In 1964, mineral revenues in Louisiana made up nearly 60 percent of the state’s budget. But the industry’s contributions to the state have continued to fall, making up less than 5 percent of the state’s budget in 2022, according to Upton’s presentation.

“Oil and gas ran the Capitol for a long time,” Landry said. “It’s not coming back like all these people want.”

Legislation introduced by DeVillier to lower the state’s severance tax on oil has passed the Louisiana House twice — this year and in 2020. During a special legislative session held in 2020 to address Covid-19 response and hurricane recovery, Rep. Devillier introduced a different bill that would have suspended severance tax on certain oil production wells for up to two years. That bill, which was expected to cost the state up to $38 million in revenue over a five year period, passed the House and Senate before it was vetoed by Louisiana Gov. John Bel Edwards.

“During a legislative session wrought with limited access for the public to meaningfully comment on bills, proponents of this new exemption averred that the exemption would increase oil production and create jobs. Yet no legitimate evidence or testimony supports this assertion, other than the testimony of those with a vested interest through enactment of a new exemption,” Edwards wrote in his veto of the 2020 bill.

In mid-May, the Senate Revenue and Fiscal Affairs Committee attempted to offset lost revenue from HB 172 by proposing to decrease the horizontal drilling tax exemption. In response, the Louisiana Association of Business and Industry, which has ranked DeVillier among its “Most Valuable Policymakers,” announced that it had switched its position from being in support of the bill to opposing the legislation. “In its current form, while lowering the fiscal note, the bill would subsidize one sector of the energy industry at the expense of another,” the lobbying group wrote in its weekly newsletter.

The following day, DeVillier pulled the bill from its Senate committee vote. The legislative session ends next week.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts