The costliest disaster in Canadian history took place in May 2016, when a vicious wildfire swept through Fort McMurray, forcing roughly 90,000 people to evacuate a city at the heart of Alberta’s oil sands industry. Seven years later, out-of-control wildfires once again threaten the province, forcing tens of thousands out of their homes and causing air quality warnings across the Western U.S. and Canada — the smoke was even visible all the way in New York City.

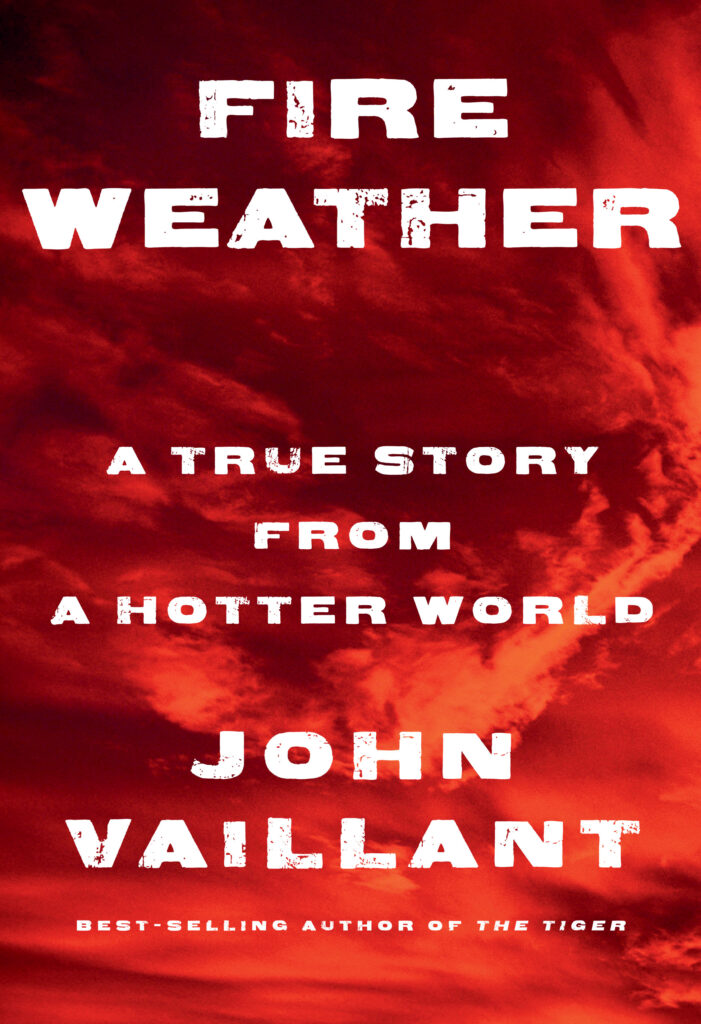

Vancouver-based author John Vaillant knows better than most the ultimate causes of these disasters and the lifelong impacts they have on communities. His new book Fire Weather: A True Story from a Hotter World, which comes out June 6, tells the story of the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire in horrific, page-turning detail. He sees that inferno, and the current western Canadian blazes, as the inevitable result of an economic system reliant on petroleum energy — as well as political leaders, such as newly-elected Alberta premier Danielle Smith, who seem willfully blind to the dangers of a changing climate.

My interview with Vaillant, the highly celebrated author of previous bestsellers The Golden Spruce and The Tiger, has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Geoff Dembicki: What’s your reaction to seeing all of these out-of-control wildfires in Alberta right now?

John Vaillant: These conditions are almost identical to the conditions that set up the Fort McMurray catastrophe. There are two things that are really heavy for me. I know from researching this book that people really suffer and they’re deeply wounded by the experience of evacuating from a wildfire. It’s not over when you move back in. In a way, you can never really trust again. And that’s a terrible kind of uncertainty to have. And most of us are lucky not to have it. When those people see smoke or smell something funny, they go to a different place psychologically than the rest of us.

There’s the physical damage, the psychic damage and then the collateral damage to all the people who witness it. Think of the firefighters who go into a neighborhood and there’s no way to save it. All they can do there is help people run away. The job that they’re trained to do, that they take pride in, that they’re paid to do, they can’t do it because the fire is too big to fight with.

And with residential fires there are tons of petroleum products of all kinds vaporizing. So people are being poisoned. It’s not just wood smoke. It’s serious chemicals. My understanding from interviews I did with firefighters following the 2016 Fort McMurray fire is most of them are resigned to the fact that their lives are shorter now as a result of several weeks of exposure to toxic air.

Dembicki: People always seem to act surprised when these disasters hit, and yet the science has been telling us for years that climate change is making wildfires worse. What do you make of that?

Vaillant: The Fort McMurray fire, and these other fires we’re seeing in Alberta, are a microcosm. We have good data, we have good scientists, we have good forecasts. Then there comes a point where you’re just going about your business, going to school, going to work, and an hour and a half later houses are burning down. Right now evacuations are underway in Alberta. It’s poignant and maddening. I’m really angry because all this was avoidable.

Dembicki: I imagine many readers of your book would be surprised to learn that the first oil sands company was warned about climate change in the 1950s. Why didn’t executives act on this information?

Vaillant: I think you can be told all kinds of stuff and you still can’t believe it until it’s in your face. That’s not all necessarily malicious. I really think there are limitations to human cognition and human psychology. We have not evolved to be able to meaningfully anticipate futures that are really dissonant to what we’re used to.

And so I think, you know, when atomic bomb inventor Edward Teller told the oil and gas industry about the greenhouse gas effect in 1959, executives maybe thought, ‘he’s a genius but he’s also kind of a nut bar, wanting to make these crazy bombs. He’s got some theory about CO2 and ice caps, but you know, that’s not going to happen in my lifetime. And there’s no way my little operation up in Fort McMurray is going to make a difference globally.’ I really think you could rationally, reasonably persuade yourself of that.

But then there’s this other component that is really crucial. There’s this almost kind of psychotic dovetailing of the capitalist impulse with Old Testament Genesis-level entitlement. And when you get evangelical Christianity and libertarianism and capitalism in the same room together, really dangerous scary things happen. Because people get this kind of single-minded righteous fervor. It’s this idea that the capitalist model is a righteous one and that it has its own laws and you have to trust the laws with an almost blind faith.

Dembicki: When the Fort McMurray fire happened it was considered extremely controversial to link that to climate change. But now there’s a study showing that historic carbon pollution from top fossil fuel companies is responsible for over a third of wildfire burn zones across the western U.S. and Canada. Has our understanding of these disasters changed?

Vaillant: Oh, it absolutely has. Certainly in the scientific community that is not captive to some aspect of the petroleum industry, people are clearly seeing the connection. Obviously, there are plenty of people in Alberta who are concerned about climate, who have some understanding of the science. But as far as the powers that govern the province, they are still heavily influenced by oil and gas.

For the rest of the world that is not bound by those constraints, it’s abundantly clear, especially if you talk to any hydrologists or scientists, that the forest has been drying out since the 1950s. We’re already seeing measurable climate change. Glaciers have been in retreat since 1900. We have to be honest with ourselves and I think most people are prepared to do that.

But for people who are dependent on the petroleum industry, that can create a dissonance. It’s very uncomfortable when your whole financial picture is dependent on this industry. In Fort McMurray and the Alberta oil patch, you play with the team. You don’t ask too many questions and you work hard, work overtime and get rewarded — that is, until you’re laid off, or worse.

John Vaillant will be launching Fire Weather at Elliott Bay Books in Seattle on June 6 at 7 p.m. See more events.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts