A UK government agency has provided billions of pounds worth of financial support to the high-carbon aviation sector since the Paris climate agreement was adopted in 2015, DeSmog analysis shows.

UK Export Finance (UKEF) has effectively subsidised new airports, aircraft, and maintenance, despite stating that the oil-dependent industry is unlikely to begin cutting emissions “materially” until the 2030s.

Over half the financial support provided by UKEF since the landmark climate accord has gone to aviation, with Rolls Royce, Airbus, Boeing, and British Airways taking the lion’s share. UKEF offers a range of loans, insurance and guarantees to help British companies secure business abroad.

Just one of the 62 deals supported, listed in the agency’s annual reports, came with any climate-related conditions attached.

Aviation accounts for the majority of the greenhouse gas emissions currently generated by UKEF’s finance, according to its latest estimate: 8.2 million tons, equivalent to putting 1.8 million petrol-powered cars on the road.

Wera Hobhouse, the Liberal Democrats’ climate spokesperson, said: “Getting to net zero needs to be at the heart of any policy decision. We are wasting time we do not have by ignoring this reality and it is having a real, damaging effect on the planet.

“The government, by not putting conditions onto contracts that would force high-emitting sectors to decarbonise, are ignoring actions that would help us avoid the grim prospect of missing our climate targets”.

Sam Pickard, research associate at international development think tank ODI, called the findings “frustrating”. He said UKEF could “play an important role in decarbonising UK exports and facilitating a rapid transition to net zero, but its continued support for the expansion of the aviation industry today is instead locking us all into more carbon emissions for decades to come”.

Aviation Exposure

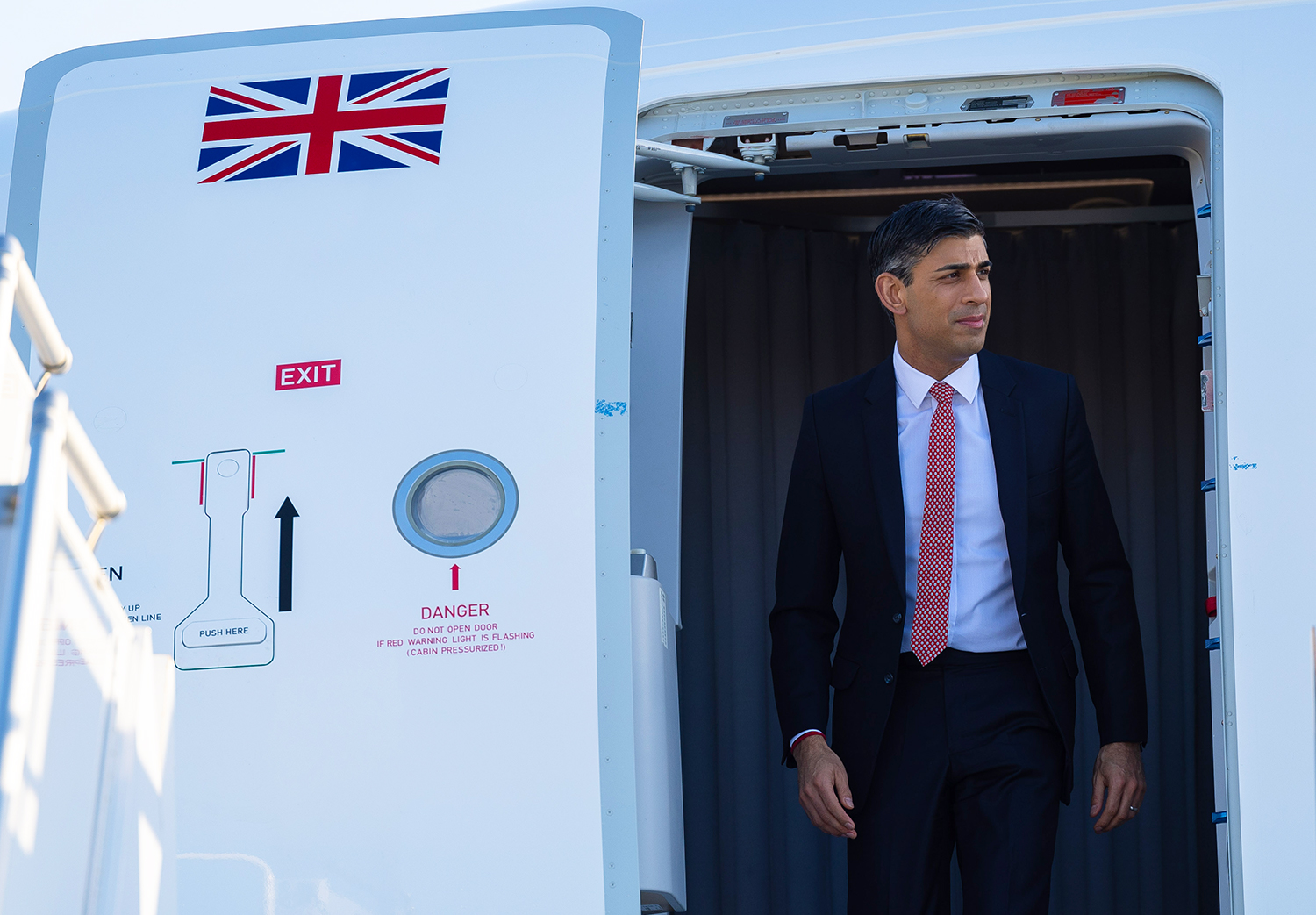

The Department for International Trade, which has recently been merged with the Department for Business, had control over UKEF during the period analysed and was led successively by Liam Fox, Liz Truss, and Anne-Marie Trevelyan, before current Trade Secretary Kemi Badenoch took over in September.

In UKEF’s latest report, covering 2021-22, Trevelyan and the then Exports Minister Mike Freer wrote that not a “penny” had gone to overseas fossil fuel projects during the year.

In the 2020-21 accounts, Liz Truss and Graham Stuart – the latter now serving as the UK’s Climate Minister – described the agency as a “leading supporter of sustainable exports” with a “critical” role in helping companies “transition away from fossil fuels”.

But in seven years, £18.5 billion of the agency’s nearly £36 billion in listed financing has been directed to the aerospace sector.

Civil aviation accounts for 46 percent of this figure, with British Airways receiving £3 billion, Airbus £2 billion, Boeing £1.7 billion, and Rolls Royce £1.3 billion.

The majority of this finance has been for deals supplying aircraft and engines to passenger airlines in countries including South Korea, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Ethiopia, Ireland, and Israel. Airbus accounted for 20 of the 31 deals of this kind.

Military deals with Qatar, Indonesia and Oman make up 36 percent of the total, with most involving the UK-based aerospace giant BAE Systems. The largest military-aerospace project was a £2.3 billion loan to the Qatari government for the purchase of jets from BAE in 2018-19.

Military projects are likely to emit considerably less than commercial projects because the aircraft are used less frequently. But scientists have previously warned of a blind spot over military-related emissions, including a “loophole” on reporting them in the Paris Agreement.

The remaining 18 percent went to Rolls Royce, which manufactures both civil and military aircraft parts, in unspecified support during the Covid pandemic.

The British Aviation Group industry body states on its website that it works “extremely closely” with the Department for International Trade, while it also provides information and support to its members on how to access UKEF finance.

A spokesperson for UKEF, who did not dispute DeSmog’s findings, said: “UK Export Finance supports British businesses, such as the aerospace sector, to export and grow the economy. During the pandemic, UKEF supported the aviation industry with £7.4 billion to safeguard the industry and jobs.

“UKEF is working with aerospace customers to help decarbonise the sector. This year we are setting a decarbonisation target for our aviation exposures to help deliver our pledge to net zero transition by 2050.

“The government has made its commitment to tackling climate change clear. UKEF has provided over £7 billion of support for green and sustainable projects since 2019 and continues to put an even greater emphasis on supporting future clean growth exports”.

UKEF pledged to end support for fossil fuel projects two years ago at the COP26 climate talks – a commitment that won praise from green groups.

DeSmog has previously reported on the significant donations made by aviation-linked individuals and companies to political parties, particularly the Conservatives. Airbus gave a total of £35,000 to the Tories between 2015 and 2018, according to official records, though there is no suggestion that the UKEF financing was influenced by any of the donations.

The Conservative Party and the British Aviation Group did not respond to requests for comment.

Pandemic Support

With flights grounded, UKEF backing for the aviation industry surged during the first two years of the Covid pandemic, amounting to over £8 billion in 2020-21.

More than £6 billion worth of support was provided in the form of “export development guarantees” to Rolls Royce and airlines British Airways (BA) and easyJet, which saw the government take on liability for commercial loans to the companies. A further £1 billion guarantee was provided to BA last year.

Campaigners queried the use of export finance to prop up airlines during the pandemic. “There are so many questions to ask here. What aspect of these airlines’ operations qualified as an export in need of government financial support? Why were they not able to get this from the private sector?” said Cait Hewitt, policy director at the Aviation Environment Federation, a non-profit group.

“And how – meanwhile – does bailing out airlines like BA and easyJet square with UKEF’s commitment to support decarbonisation? Aircraft are powered almost 100 percent by fossil fuels and the aviation minister herself said recently that aviation is likely to be one of the highest-emitting sectors in the country by 2050.

“Airlines already benefit from paying no duty on their fuel, and most of the emissions from flying attract no carbon costs. There’s always been a suspicion that airlines and airports benefit from backroom deals with the government. This loan money looks particularly murky”.

Additionally, BA and Rolls Royce each received £300 million in emergency loans from the Bank of England in 2020, with easyJet awarded £600 million, according to a Guardian analysis.

Campaigners urged the government to make its bailouts conditional upon airlines adopting decarbonisation plans, but were disappointed by a lack of new targets. Only the more recent £1 billion loan guarantee to BA came with a “sustainability-related performance clause” designed to push the company in a greener direction.

A UKEF spokesperson defended the aviation support as necessary to help the industry weather the pandemic but did not clarify how this clause would require BA to go beyond its existing commitments, which include a 2050 net zero emissions target.

Some economists at the time warned that unconditional airline bailouts would have the lowest economic benefit and highest negative climate impact among a range of suggested support packages for different sectors.

UKEF support for aviation has also continued in more recent times, including an £89 million deal with Brazilian manufacturer Embraer celebrated by the government in October.

Lack of Decarbonisation Progress

Current efforts by domestic and international agencies to tackle growing aviation emissions have been criticised as inadequate for relying on voluntary pledges by the industry, as well as disputed carbon offsets.

Growth in aviation demand has outstripped efficiency improvements and the sector contributes an estimated 3.5 percent of global emissions when warming effects at altitude are taken into account. Passenger numbers are expected to continue rising significantly in the coming decades.

Flights often represent a sizeable proportion of an individual’s carbon footprint in wealthy countries like the UK, where the sector contributed over 8 percent of national emissions in 2019. An analysis in 2021 estimated that BA alone produces emissions equivalent to almost all vans driven in the UK combined.

In its latest accounts, UKEF says that aviation is “widely acknowledged” as “one of the more difficult sectors to decarbonise globally”, a process it says will “not begin materially until the 2030s”. It says this is due to the time needed to develop “sustainable” fuels and other green technologies, many of which are criticised as environmentally damaging or economically unviable.

A recent report by the Royal Society estimated that vast resources would be needed to replace jet fuel based on current demand. Hydrogen would require double the amount of renewable energy currently being produced in the UK, while ‘e-fuels’ would require five times as much. Up to 68 percent of UK farmland would be needed to produce enough crop-based biofuels, which still generate emissions when burned.

The industry has been criticised for having a poor track record of meeting climate targets, with a report last year finding that it had missed all but one agreed since 2000.

“UKEF knows there is no prospect of widespread carbon neutral flying any time soon”, said Pickard from ODI. Its aviation support is therefore “simply driving up oil consumption and carbon emissions in a sector that has continually dodged its climate obligations”.

Green Projects and a Petrochemical Plant

DeSmog’s analysis of UKEF’s annual reports shows that the agency has ramped up its support for climate-friendly projects in recent years, including a solar farm in Turkey, monorail lines in Egypt, and a loan guarantee to aid car manufacturer Jaguar Land Rover’s transition to electric vehicles.

But, overall, only 16 percent of finance provided by UKEF since the Paris Agreement can be classed as explicitly green, with just four percent going to renewable energy.

And although the agency’s latest report does not list any new fossil fuel projects, this policy has been put in doubt by the news in February that UKEF is backing a new petrochemicals plant set to be built in Belgium.

This project, which developer Ineos says will be the “greenest” in Europe, will be fed with fracked shale gas from the United States and is the subject of a legal challenge by environmental groups.

Spain and Italy’s export credit agencies, which signed onto the UK-brokered COP26 commitment to end public finance for “unabated fossil fuel energy” by the end of last year, are also backing the project.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts