A discrimination lawsuit filed Tuesday in the Eastern District of Louisiana alleges that the St. James Parish Council steered polluting facilities into Black neighborhoods along the Mississippi River. As a result, Black residents there are forced to breathe in more pollution and face a higher risk of related health problems, according to the suit filed by Inclusive Louisiana, Mount Triumph Baptist Church, and RISE St. James.

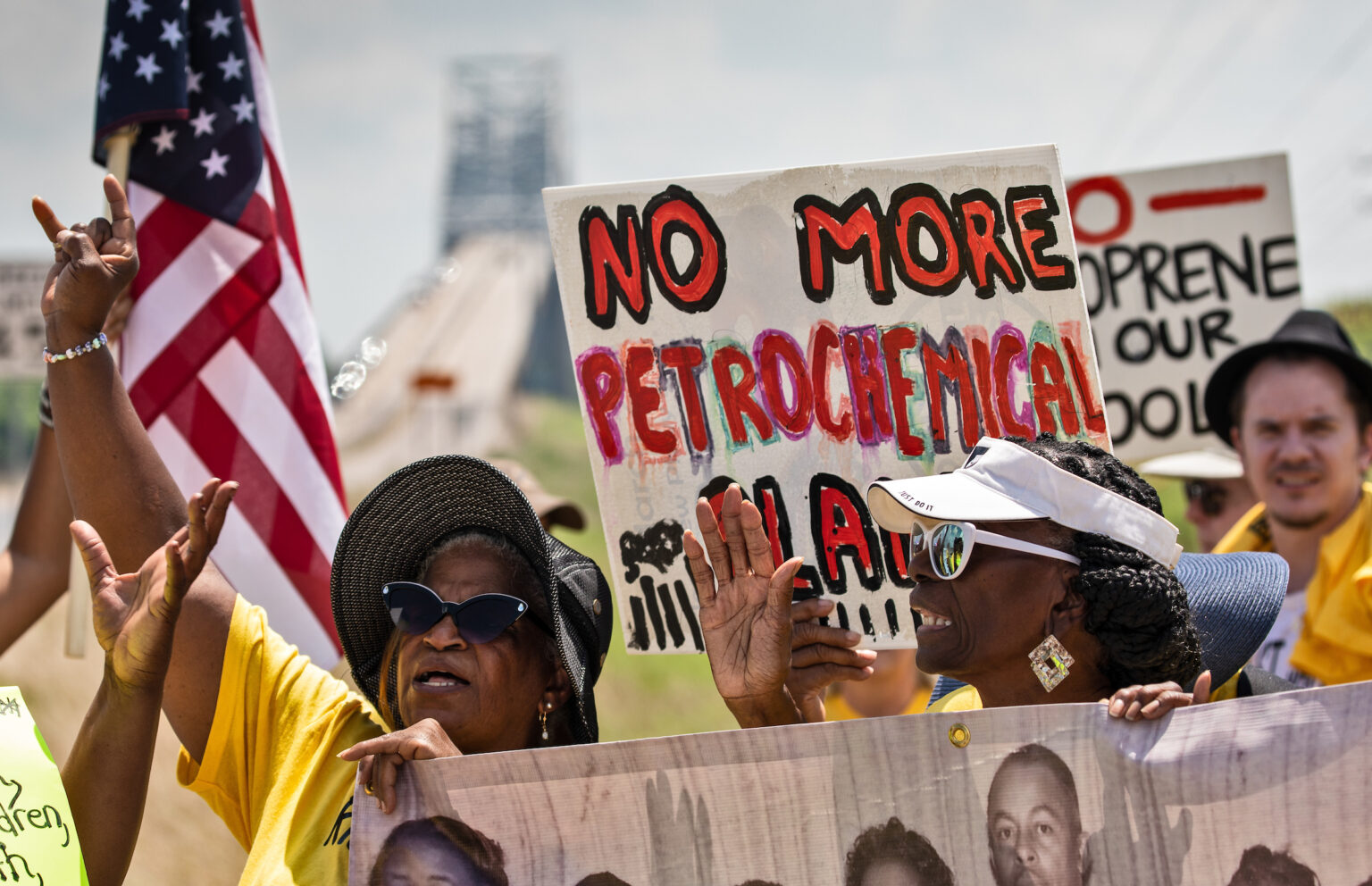

“We’re being ignored and we have to do whatever we have to do to stop it,” said Myrtle Felton, a lifelong resident of St. James Parish and co-founder of Inclusive Louisiana, a community group focused on environmental injustices.

St. James Parish is situated in the heart of Cancer Alley, the 85-mile corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans where more than 150 chemical facilities are located. Before the Civil War, much of the parish was made up of sugarcane and tobacco plantations. Plaintiffs in the lawsuit say they are descendants of people who were enslaved on these brutal plantations. They are being represented by attorneys with the Center for Constitutional Rights and Tulane University Environmental Law Clinic.

The parish is split by the Mississippi River with the two majority Black districts — the 4th District and 5th District — across the river from each other. In 2014, the predominantly white seven-member parish council adopted a land use plan that labeled large areas of these districts “industrial” or “existing residential/future industrial,” encouraging industrial development in or near residential areas. Soon after, oil storage tanks, and later, a pipeline sprouted in the fields across from homes of Black residents.

There are now 11 facilities in the districts that must report their emissions to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Toxic Release Inventory, a database of facilities that release air pollution known to cause cancer and other adverse effects to human health and the environment.

The St. James Parish Council’s Legal Advisor, Adam Koenig, has not yet responded to DeSmog’s request for comment on the lawsuit.

Over the past 26 years, no new polluting facilities have been approved to be built in the majority white areas of the parish, according to the lawsuit. Still, companies have tried to build more petrochemical facilities in the Black districts with the approval of the council, including Formosa’s planned $9.4 billion Sunshine Project. The plastic manufacturing complex would emit more than 6,000 tons of air pollutants regulated by the Clean Air Act, according to the lawsuit.

In 2019, plaintiffs wrote a letter to St. James Parish council members that asked for a moratorium on new petrochemical facilities and pipelines in their communities, citing concerns of discrimination and health risks. But no action was taken.

Last September, a federal judge ruled against the state of Louisiana for issuing air permits to Formosa for its St. James plastics project, describing the environmental justice analysis as “arbitrary and capricious,” the latest in a number of setbacks for the plastics complex. Faith-based community group RISE St. James was also involved in that lawsuit.

Gail LaBoeuf, one of the signatories of the 2019 parish council letter and a co-founder of Inclusive Louisiana, has been diagnosed with liver cancer and is currently undergoing chemotherapy.

“We know we’re not unique, that this is going on in the rest of America,” LaBoeuf said. “But we’re showing the rest of America how to fight it.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts