Translated from the original published at climatica.lamarea.com.

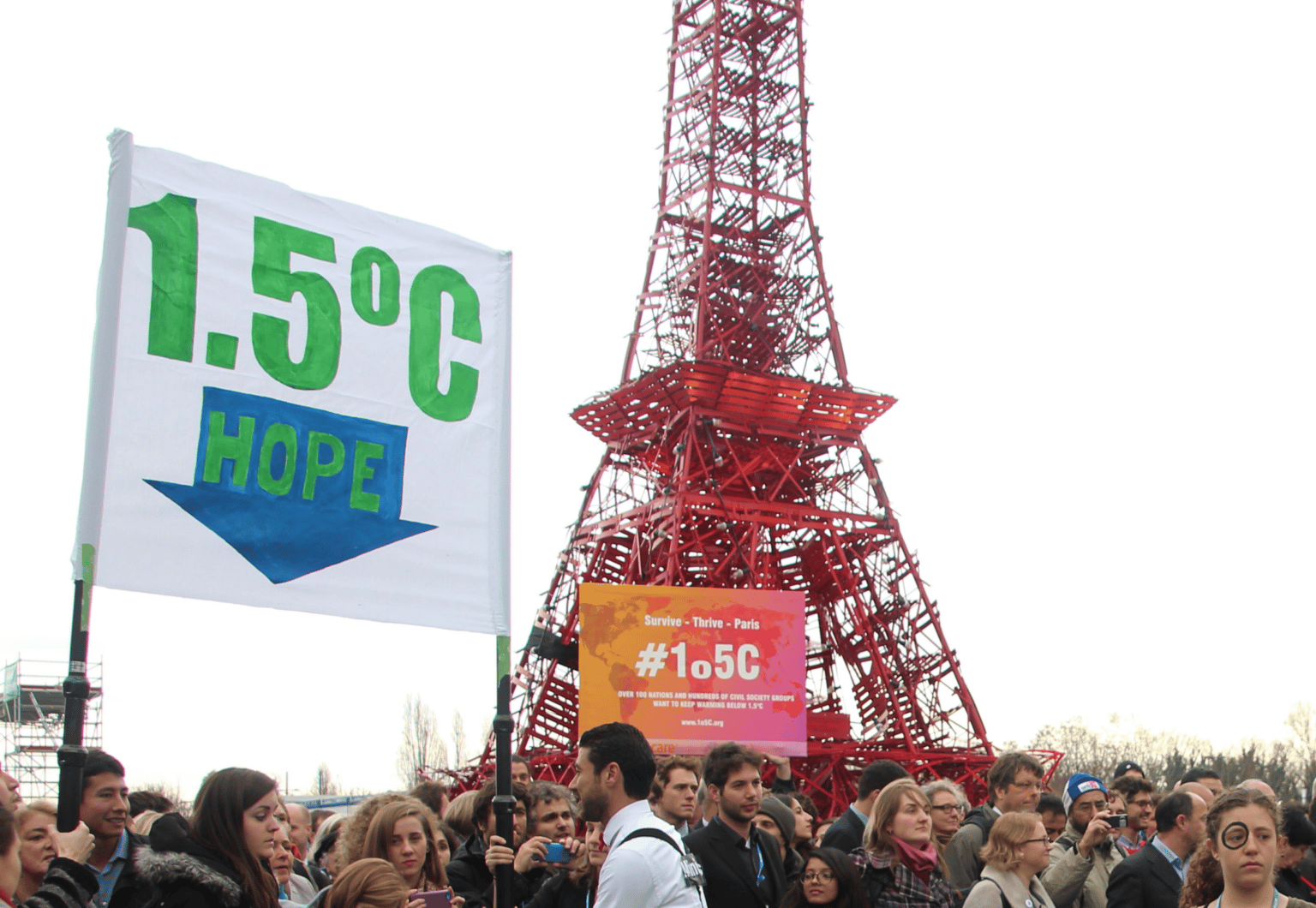

Two numbers. One long-term goal. In 2015, nearly 200 countries agreed to “Holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels, recognizing that this would significantly reduce the risks and impacts of climate change”. It was at COP21, where the Paris Agreement, the most important climate pact to date, was enshrined.

That paragraph, in article 2, paragraph 2.a., marked a before and after. Every policy, law, regulation, study, analysis, proposal or action that has the climate crisis in mind is built on the basis of those two figures: 1.5 and 2. They are our lighthouse. But why are both numbers so important? And what is even less well known: where do they come from?

The answer is neither simple nor short. Like a chicken and egg dilemma, who came up with these goals first, politics or science? In the following lines, we will try to unravel their origins and understand how two numerical targets have ended up guiding and influencing the planet.

Just as the legend that babies come from storks from Paris is not true, temperature limits did not magically appear during the summit in the French capital. Nor did they appear at the same time, nor has the same language always been used to refer to them, as will be seen below.

The Scientific Origins of 2°C

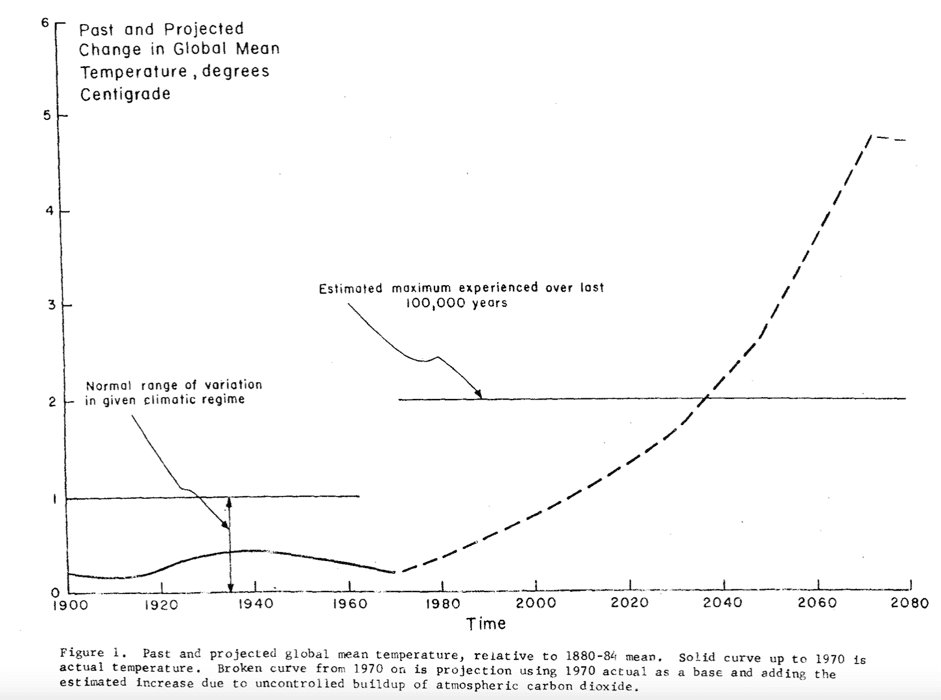

We have to go back to the last century to find the first references to 2°C. Specifically, to 1975. That year, the American economist and 2018 Nobel laureate William D. Nordhaus published an article in the American Economic Review entitled Can We Control Carbon Dioxide? In it, he argues that “if there were global temperatures more than 2° or 3° above the current average temperature, this would take the climate outside of the range of observations which have been made over the last several hundred thousand years.” Two years later, he publishes another article where he insists on the same idea, and accompanies it with a revealing graph.

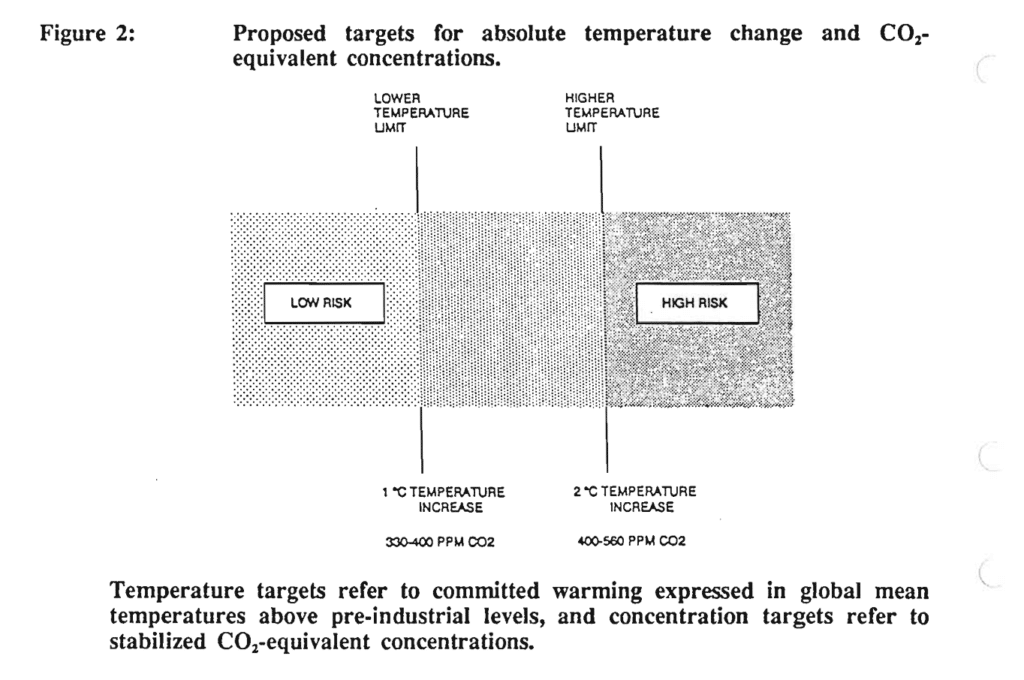

Fast forward to 1990. In the same year that the first-ever IPCC report is published, a report by the Stockholm Environment Institute is produced and signed by scientists Frank Rijsberman and Rob J. Swart. In it, they identify “two absolute temperature targets for committed warming.” These limits imply different levels of risk, they say. The first referred to a global average temperature increase of 1°C above pre-industrial times. The second referred to a 2°C warmer planet.

Even then, the authors recognised that “an absolute temperature limit of 2.0°C can be viewed as an upper limit beyond which risks of grave damage to ecosystems, and of non-linear responses, are expected to increase rapidly.” It was accompanied by the following figure:

“Our report was perhaps the first to formulate a recommended provisional temperature target by the scientific community to the world’s policy makers” and “recognized the world would probably already exceed 1 degree warming based on unavoidable emissions,” says Frank Rijsberman, who led the project. He says the work was commissioned by the AGGG (Advisory Group on Greenhouse Gases), a body set up in 1985 by the World Meteorological Organisation and UN Environment, which was the precursor to the IPCC, created in 1988. “The workshop was a small affair bringing together some 25 prominent scientists, very unlike the thousands now involved in IPCC,” he explains.

However, Rijsberman believes that the report’s greatest scientific contribution was another. For the first time, it proposed encompassing all the gases that cause global warming in a single indicator. “It was the most controversial and heated debate in the workshop,” recalls Rijsberman, now director of the Global Green Growth Institute. Thirty years later, this novel idea is universally established. It is what we know today as CO2 equivalent (CO2eq).

Political Origins of 2°C

The next key moment in the 2°C story is no longer scientific, but political. But first, it is important to highlight other milestones that, while not directly addressing these temperature targets, served to put the climate issue on the agenda. On the one hand, there was the forceful intervention on the dangers of climate change by NASA scientist Dr. James Hansen before the U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources. It was 1988, and the expert was already warning about the existence of anthropogenic global warming and how it was influencing extreme events such as heat waves.

Then there was the signing of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Article 2 of the Convention states as its main objective the “stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.” At the time, no mention was made of a temperature limit. For a long time, the debate focused more on CO2 concentrations than on warming levels.

And we reached the political tipping point around the two-degree mark. On June 25-26, 1996, the European Council of Environment Ministers agreed during its meeting that “global average temperatures should not exceed 2 degrees above pre-industrial level and that therefore concentration levels lower than 550 ppm CO2 should guide global limitation and reduction efforts.” This is the first time that the 2°C target has made the leap into the political sphere. A decade later, in 2005 and 2007, EU heads of government would confirm this path. Among the signatories of that declaration were former German chancellor Angela Merkel, then environment minister.

“After the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, scientists worked hard to define ‘dangerous climate change,’ usually based on specific ecological limits,” says Piers Forster, Professor of Climate Physics at the University of Leeds with a long history of contributing to IPCC reports. According to the expert, “international policy focused on a CO2 concentration limit until the early 2000s because it had more precedent in the literature, was the basis of the target when UNFCCC was set up and, for a given future emission pathway, could be estimated with more certainty than the level of warming.”

A year before the European Council of Environment Ministers, there was a key milestone in this whole story. The German Advisory Council on Global Change, which produced a series of reports during those years, issued a statement arguing that, in order to achieve “preservation of Creation” and “prevention of excessive costs,” “the temperature span to the tolerable maximum” was “only 1.3°C” compared to 1995, (but compared to pre-industrial times, that maximum limit was 2°C). This institution and its then vice-president – physicist Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, who was director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research – were instrumental in convincing Merkel of the importance of the 2°C target, first at the previously mentioned European Environment Council and then, as we shall see, at a G8 summit.

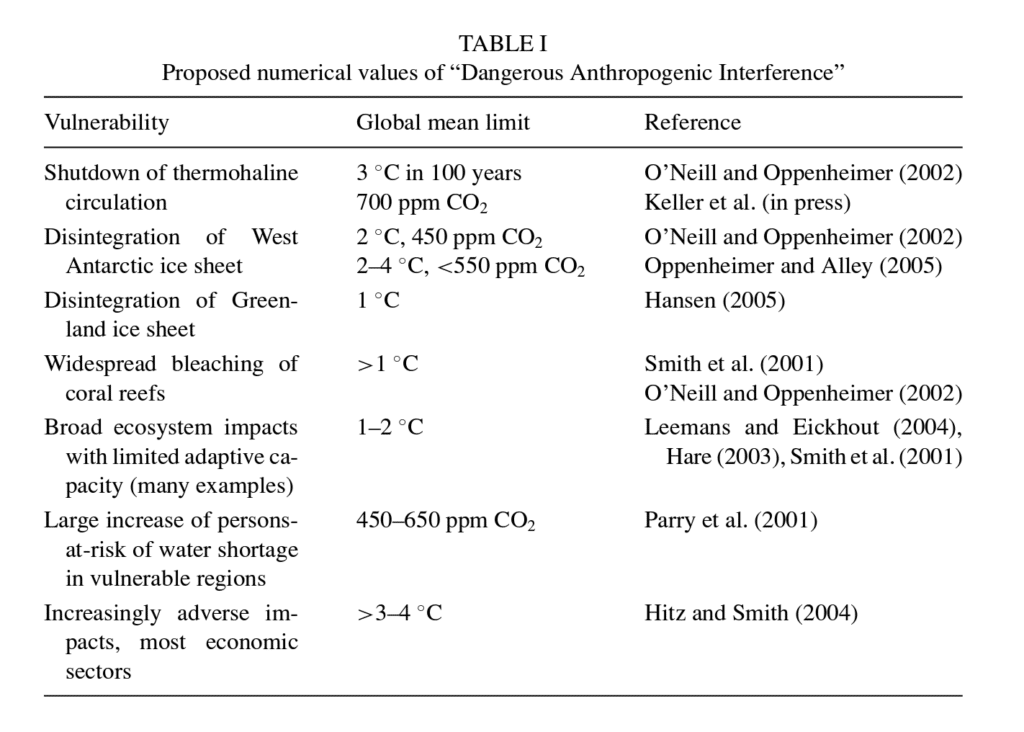

Momentary return to science. In 2002, U.S. scientists Brian C. O’Neill and Michael Oppenheimer published an article in which they spoke of specific risks depending on the degree of warming. Although that study was based on the year 1990, it already stated that “a limit of 2°C above the global average temperature” was vital “to protect the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS).” They also advanced the now established fact that “a long-term target of 1°C above 1990 global temperatures would prevent severe damage to some reef systems.”

“At the time, it would have been difficult to differentiate between, for instance, 1.3 and 1.5 or 1.5 and 1.8 in terms of impacts. In fact, it’s still difficult to do so today,” says Oppenheimer. “Most important is that we know every tenth of a degree of warming makes the impacts more and more dangerous and that the higher the temperature, the more and more rapidly the frequency of many types of extreme events increases,” he adds.

Another time jump. It is 2009 and the 35th G8 Summit. The political leaders – including Merkel, Sarkozy, Obama and Berlusconi – sign a declaration in which they recognize “the broad scientific view that the increase in global average temperature above preindustrial levels ought not to exceed 2°C.” Key to this were the IPCC’s Second (1995), Third (2001) and Fourth (2007) Assessment Reports. In all of these there were already projections of temperature increases, including 2°C.

This was coupled with another statement, that of the Major Economies Forum on Energy and Climate, which also recognized the importance of limiting warming to below 2ºC. “t was the first time that a consensus had been reached between the main developed and developing countries regarding the 2°C target,” reports a scientific paper published in 2017 that traces the evolution of this target.

At the end of 2009, the Copenhagen climate summit, COP15, was held in Copenhagen. It remains in memory as one of the most disastrous summits ever organized. To some extent it was, as it ended with a text that was not unanimously recognized by all parties and had no legal effect. Even so, it was a major breakthrough as the first COP to mention the temperature goals we are all familiar with today. The outcome document took into account “the scientific view that global temperature increase should remain below 2°C.”

A year later came COP16 in Cancún. The agreement states that “deep cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions are required […] so that the global average temperature increase compared to pre-industrial levels is kept below 2°C.”

Finally, in 2015 came the momentous COP21, where the Paris Agreement was sealed. The 2ºC target (and the 1.5ºC target) became the consensus of the international community. Everything had changed forever. And a key point: “The language around 2°C was strengthened in response to emerging science, moving from ‘stay below 2°C’ at the Cancun COP to ‘stay well below 2°C,’ which implies a much higher probability of never exceeding that level,” notes Dr. Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, Head of Climate Science at Climate Analytics.

“The 2°C limit is what we call a social construct. This means that politicians, scientists and policy makers associated with the UN Climate Change Convention process sought a balance between what the science said, the possible impacts, and the amount and speed of mitigation that seemed possible. And, therefore, in being successful in meeting the goal of limiting the temperature to below 2°C,” reflects Pep Canadell, executive director of the benchmark Global Carbon Project, which monitors CO2 emissions each year.

1.5°C: the Closing Window

Studies on the dangers of exceeding 2°C warming and political attempts to set it as a target have had a long history. Science has been introducing the idea since the 1970s and, little by little, politics has taken it as a reference to guide climate action. However, the emergence of the 1.5°C limit is more recent and intense.

The story of how that lower limit became enshrined belongs to a large number of small island countries and vulnerable regions. Their territories were going to be the first victims of global warming, so they decided to stand up to the bigger nations for a more ambitious goal. And so they fought. And they won.

In 1990, the article by Frank Rijsberman and Rob J. Swart – mentioned at the beginning – pointed out that “temperature increases beyond 1.0°C may elicit rapid, unpredictable, and non-linear responses that could lead to extensive ecosystem damage.” In subsequent years, more studies along the same lines followed. However, the exact 1.5°C target emerged less recently than we thought.

The year was 2008. The 14th climate summit was held in Poznan (Poland). It ended without much of a story, with the parties being called to the COP the following year. However, on December 11, in the final stretch of negotiations, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) called for a limit of 1.5°C temperature rise and greenhouse gas concentrations of no more than 350 parts per million, as well as a 40% reduction in developed country emissions by 2020 compared to 1990 levels. For the first time at a COP, a target of 1.5 rather than the 2°C to which the more developed countries were sticking had been put on the table.

Throughout 2009, small island and coastal nations, as well as other vulnerable countries, took advantage of any space where they were present to call for greater climate ambition, with the 1.5 degree limit as the main demand.

The Maldives did so at the sixth preparatory meeting for the COP in Bonn, Germany, and Grenada (on behalf of AOSIS) did so at the seventh meeting. In September of that year, the AOSIS heads of state met in New York, where they agreed on a Declaration on Climate Change. In it, they once again called to “reinforce the UNFCCC process, by calling on the big emitters to agree to produce enough clean energy to attain the targets of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degree Celsius and 350 parts per million of atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations.”

The Climate Vulnerability Forum (Bangladesh, Barbados, Bhutan, Ghana, Kenya, Kiribati, Maldives, Nepal, Rwanda, Tanzania and Vietnam) also joined the call and decided to issue a statement which, among other issues, called on developed countries “to secure climate justice for the world’s poorest and most vulnerable communities,” and asked them to commit to “limiting global average surface warming to well below 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels.”

The work to spread the word about the need for a more ambitious target was intense. “By that time, the 1.5° goal had also been socialized with other groups within the G77 at the request of the AOSIS coordinator and by the AOSIS Shared Vision coordinator,” notes scientist Bill Hare, who recalls that other groups, such as the Independent Association of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC), as well as countries on a bilateral basis, were also consulted.

It is important to note that “achievement of the 1.5 target was not just a series of decisions made at the COP,” says Leon Charles, chief negotiator for AOSIS while his country, Grenada, chaired the group (2007-11). He sees “significant efforts to mobilize and build support as part of an outreach strategy after the target was first presented in Poznan” as key.

The pressure had been sustained throughout 2009 and, with the debate at its peak, a new climate summit – COP15 in Copenhagen – arrived at the end of the year. Thanks to a year of outreach and lobbying, more than 100 developing countries were already supporting the 1.5 target that AOSIS had pushed for at the previous COP.

The need to come out of the summit with a win was vital. So much so, that Tuvalu – the world’s fourth smallest nation – rose up during the negotiations and managed to stop them on several occasions. The tiny Pacific Ocean island of just 12,000 people was insistently demanding, along with AOSIS and LDCs, a legally binding treaty that would keep the temperature rise below 1.5°C. They were simply asking for it. They asked for it simply because with 2°C warming, their territory will succumb to rising sea levels. “How can you ask for my country to become extinct?” Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed asked the Chinese delegate, who asked for the proposal to be removed from the text. They even had a slogan: “1.5 to stay alive”.

Scientific Origins of 1.5

The first political stepping stone to push for 1.5 came in 2007. That year, COP13 took place. It concluded the so-called Bali Action Plan. Among other issues, it included the development of “a shared vision for long-term cooperative action, including a long-term global goal for emission reductions.” AOSIS decided to include among its contributions to the plan – which was due to be finalized at COP15 – the 1.5 target. Then came Poznan and Copenhagen, as explained above. But the more scientific origin of the 1.5 remains to be seen. On what basis did island and vulnerable countries claim for so many years a warming target below 1.5°C?

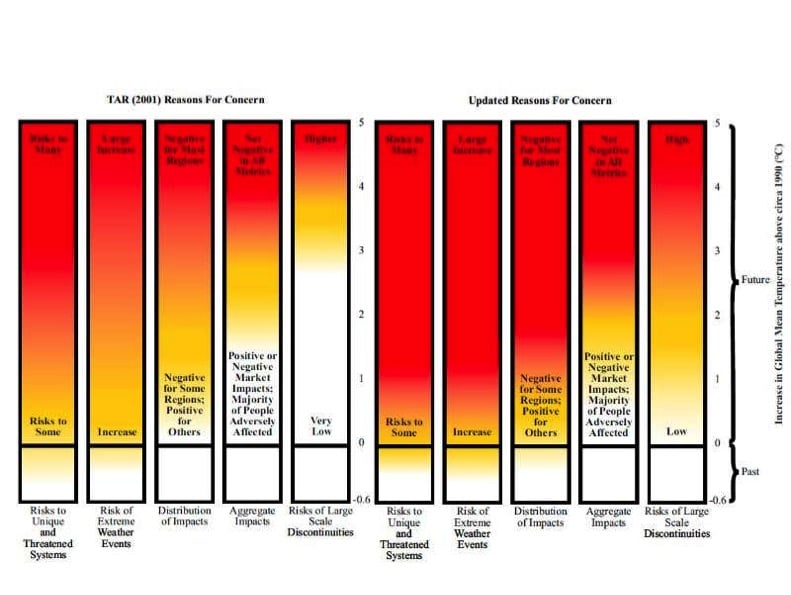

A first origin may be “the ‘burning embers’ graph in the IPCC’s Third Assessment Report (from 2001), which showed the dire consequences for small island developing states with temperatures above 1°C above pre-industrial levels,” says Ian Fry, Tuvalu’s representative at COP15 and now Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights in the context of climate change at the United Nations.

However, the IPCC’s Fourth Assessment Report (AR4), published in 2007, was more categorical. The alliance of small and most vulnerable countries was concerned that the impacts of 2°C warming described by the UN-linked panel of specialists were too dangerous for them.

While AOSIS fought in international forums for a target that would not threaten their territories, they decided to commission the German organization Climate Analytics to carry out a series of analyses to find out what they were really up against. “We were running a project together with PIK called the PREVENT project which is designed to provide scientific and technical support for the small states and least developed countries,” explains Bill Hare, founder and executive director of Climate Analytics, a lifelong climate science and policy expert. “The modality was AOSIS and/or LDCs requested work from us on different issues, including on 1.5C questions,” adds Hare, who is also a physicist and climatologist.

In the last quarter of 2009, just before the COP15 in Copenhagen, several key reports on temperature limits were delivered to the vulnerable nations. “A review of recent scientific literature as well as the findings of the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) however indicates that a warming of 2°C would have unacceptable consequences for small island developing states and other highly vulnerable regions,” advised the first of the Hare-led reports. In a subsequent paper, PREVENTwarned that “limiting warming below 1.5°C is much safer and will give natural systems a much better chance to survive and adapt as well as avoiding serious damage to LDCs ecosystems.” It also made clear that “limiting warming in the longer term below this level, would bring greater certainty in avoiding the worst impacts of climate change. It will reduce but not eliminate major risks and damages to LDCs, and will still require major support from the international community for adaptation.”

Politics Pushes Science

Despite the enormous work that AOSIS had done in the background, the final non-binding text reached at COP15 in Copenhagen focused on the 2°C target. This outcome was motivated by the fact that the document was produced by a very small group of countries, according to some of those involved. Ian Fry’s emotional speech, which concluded his plenary session with a strong but ignored message – “The fate of my country is in your hands” – did not have the desired effect. “In Tuvalu’s case, the reference to 2ºC was the breaking point. We could not accept this,” says Fry.

However, the summit was not entirely fruitless. The Chair of AOSIS refused to accept the text if it did not include a commitment to his demands. Thanks to this pressure, and with opposition from the major emitting nations, a final point was introduced into the agreement, which calls for a “review of the implementation of this Agreement” in 2015, which would “consider strengthening the long-term goal with reference to various elements raised by science, in particular in relation to the 1.5°C temperature increase.” This review, as will be seen later, was key to achieving the 1.5 limit.

The following year, in 2010, the climate summit took place in Cancún, Mexico. COP16 closed with a new call “to keep the temperature below 2°C and to consider strengthening the long-term global goal on the basis of the best available science, including a global average temperature increase of 1.5°C.

At this point, raising ambition and focusing all efforts on keeping global warming below 1.5°C was a demand that was not uncommon. The then head of UN Climate Change, Christiana Figueres, called on countries to join in this goal, and the then chairman of the IPCC, Rajendra Pachauri, urged limiting the concentration of atmospheric CO2 to 350 ppm. However, large economies and major emitting countries remained focused on 2°C.

The update in the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report of its ‘burning embers’ diagram reinforced concerns about the 2°C warming, as it implied too great of risks and impacts for small island developing states and least developed countries. According to Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, author of one of the first comprehensive studies on the different impacts between a 1.5°C and a 2°C rise, this work came too late: “The scientific community did not say much about 1.5°C before [COP21 in] Paris, despite clear references in the UNFCCC. That, admittedly, was a big oversight.”

Bill Hare, who agrees with some of the analysis made by his colleague – “There should’ve been a lot more and it was not done” – points out that “the IPCC’s Fifth Report provided guidance on impacts and risks depending on the levels of warming,” including 1.5°C and 2°C. “And this was very influential,” he says.

A Decisive Report…

Following the mandate of the COPs in Copenhagen (2009) and Cancun (2010), the Periodic Review of the Global Long-Term Objective was conducted between 2013 and 2015. The outcome was the Structured Expert Dialogue, a report summarizing the face-to-face dialogue between more than 70 experts and countries on the appropriateness of the 2 degree limit and the benefits of strengthening the global goal to 1.5. The technical summary included 10 messages. The last one said: “Although the science on the 1.5°C warming limit is less robust, efforts should be made to lower the line of defense as much as possible.” It also noted that “limiting global warming to below 1.5°C would have several benefits in terms of moving closer to a safer boundary.”

While it was made clear that the report’s findings “do not take precedence over the 5th Assessment Report of the International Governmental Panel on Climate Change, which is the formal, government-accepted document on climate science,” the UN said, this document “was instrumental in the adoption of the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal,” notes Carl-Friedrich Schleussner. This document was seized upon by the small island countries, who at the customary pre-summit meeting in Bonn again insisted that the 1.5°C target be included in the final pact.

…and the Summit That Changed Everything

This time we could not fail. The previous summit, held in Lima, served to pave the way, and the Paris summit was to be the COP that would seal the roadmap that would succeed the Kyoto Protocol and mark the climate action for the coming decades. And so it was. After years and years of struggle, demands and scientific evidence, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and the Least Developed Countries (LDCs) saw on December 12, 2015 the birth of the Paris Agreement, the first international treaty to give legal effect to the goal of “holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C.”

Until then, successive summits aimed to limit warming to below 2ºC. With the new agreement, the rules of the game change: “While some still try to argue Paris has two warming limits, they’re wrong: there’s only one, and it’s 1.5,” explains Bill Hare, who was present during the negotiation and drafting process. He adds: “The Paris Agreement’s language was carefully crafted, and a major achievement in enshrining the 1.5˚C limit into the heart of the agreement.”

Carl-Friedrich Schleussner agrees and adds that “the long-term goal [of the Paris Agreement] is ambiguous, of course. But not in the sense of ‘pick your target,'” he says. “It can be understood as never exceeding 1.5°C, or allowing for a temporary overshoot of global temperature above the 1.5°C limit while keeping warming “well below 2°C,” he argues. “It is also important to acknowledge that the temperature goal refers to temperature levels as upper limits, and not to stabilizing global temperatures, also not at 1.5°C. The intent is that temperatures should fall in the long term to a level that does not represent a ‘dangerous anthropogenic interference,'” he concludes.

And beyond this debate, Schleussner sees it as “fair to say that the adoption of the Paris Agreement’s temperature goal, and its 1.5°C limit, was based on a much more rigorous scientific assessment of the available scientific evidence than the previous Cancun target of less than 2°C.”

“The nuances are essential to understanding the story of 1.5,” points out Leon Charles. It is a story, he says, “of continuous advocacy and fight by the small island states in the 2008-2015 period, against the opposition of the developed countries and the oil producers.” And although the balance ended up on their side, it might not have been: “There were many times when it hung on a thread, but perseverance eventually won the day,” he says. “For me the AOSIS are the heroes of 1.5C though. Science is still catching up,” says Piers Forster.

Science Goes all in on 1.5

The Paris Agreement not only enshrined the long-awaited 1.5 degree target. Countries agreed to invite the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to submit, in 2018, “a special report on the effects of global warming of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels and associated global greenhouse gas emissions trajectories.”

This was done, says Professor Piers Forster, one of the report’s authors, because at the time “there were almost no papers on the 1.5 targets, as scientists did not attend COPs and were not very aware of what was going on.” Still, he praises some scientists, “especially Joeri Rogelj and Carl-Friedrich Schleussner, who were attending COPs and their early publications already supported the science around the 1.5°C limit.”

The IPCC accepted the proposal the following year and in October 2018 published what is one of the most important reports in climate science. The aim of this work is to provide policy with the maximum evidence and support for action to limit temperatures as much as possible.

“Climate-related risks for natural and human systems are higher for global warming of 1.5°C than at present, but lower than at 2°C,” the dozens of scientists involved concluded with high confidence.

The differences in impacts include an increase in average temperature, extreme heat events, precipitation, the likelihood of drought… Half a degree of warming is a matter of life and death for many ecosystems and regions. This is the case for corals and the Arctic. With 2°C of warming compared to pre-industrial times, coral reefs “mostly disappear.” However, even with a temperature increase of 1.5°C, “90% of reef-building corals will be lost compared to the current situation.”

As for the Arctic – which has warmed 3.8 times faster than the global average since the late 1970s – the report predicts that “there will be at least one Arctic summer without sea ice every 10 years at a warming of 2°C,” while “the frequency will decrease to one Arctic summer without sea ice every 100 years at 1.5°C.”

Sea level rise over centuries or millennia is already guaranteed, regardless of what is done now. According to the IPCC’s most recent work – the Sixth Assessment Report, published between 2021 and 2022 – over the next 2,000 years, global average sea level will rise by 2-3 meters (roughly 6 to 10 feet) if warming is limited to 1.5°C, while the rise will be between 2-6 meters (roughly 6 to 20 feet) if it is limited to 2°C. Between 1901 and 2018, global sea level rise is estimated to have been 20 centimeters (around 8 inches).

Limiting warming to 1.5 instead of 2°C will reduce temperature increases in the oceans, the associated increase in ocean acidity and decrease in oxygen levels. Keeping warming below 1.5 degrees also means lower risks to biodiversity, fisheries and marine ecosystems and the functions and services they provide to humans.

“The science is clear that with every tenth of a degree the impacts increase and that, with higher temperatures, the probability of new feedback processes (which will accelerate climate change) increases,” explains Pep Canadell. It’s a similar argument to that of Michael Oppenheimer, who warns that “the changes have already begun”: “Above 1.5 degrees and especially above 2C, they get more challenging to manage, very quickly.”

Another expert who stresses this idea is Jesús Fidel González Rouco, professor of physics and author of several IPCC reports: “We have learned in recent years that 0.5ºC matters.” Rouco explains that we know and can model well the risks associated with up to 2 degrees of warming. But beyond that temperature limit, he says these risks increase while our ability to quantify them decreases.

Where Are We Heading?

There's a long way from words to deeds, as the saying goes. In 2022 it will be seven years since the adoption of the climate pact that called for a degree and a half, but the reality is quite different. "The international community is still a long way from achieving the Paris Agreement targets and there is “no credible pathway to 1.5°C in place,” the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) recently criticized in its annual report on the emissions gap. So without substantial additional efforts in this next critical decade, 1.5°C will be out of reach.

Currently, the UN environment branch's warming range is between 1.8°C and 2.8°C by 2100, depending on whether pledges, current plans and implemented policies are analyzed. Be that as it may, in no case will the target be met, not even the target of keeping warming well below 2ºC.

"The planet is going to reach and exceed 1.5ºC at the beginning of the next decade, regardless of how aggressive or unaggressive we are in mitigation," says Pep Canadell. According to a recent analysis by the Global Carbon Project, which the Catalan biologist directs, at the current rate of emissions there is a 50% chance of exceeding one and a half degrees of warming in nine years, i.e. in 2031.

"The only way the models can give a pathway to stabilize the climate at 1.5 is to exceed that figure and then carry out large amounts of CO2 removal from the atmosphere, to the point where the temperature of the planet (with less CO2 in the atmosphere) can cool down a little bit and return to 1.5°C," Canadell explains.

The need to go beyond one and a half degrees and then go down, says Canadell, is because "the models we use to set the pathways to stabilize the climate do not let the economy collapse, and therefore we need more than 10 years to make the full transition to renewables." Still, he warns: "This is the theory. What nobody knows is whether we will have the capacity to remove as much CO2 as it will take to get back to 1.5°C."

Even so, as Carl-Friedrich Schleussner reminds us, the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report includes — albeit few and limited — pathways to 1.5°C without overshoot. In this respect, the expert prefers to look to the future with more optimism: "The IPCC Working Group 3 report has shown in a very detailed manner how emissions can be halved by 2030 with cost efficient measures across all sectors," he says. For the head of climate science at Climate Analytics, this is a "hopeful message that illustrates that it can be done if there is the political will to do so," and is supported by the work of the International Energy Agency, which "assesses a Net Zero Emissions by 2050 (NZE) pathway that remains narrow but still achievable."

It is true that the temperature limits set were based, to a greater or lesser extent, on science. They were adopted taking into account the differences in impacts from one degree of warming to another. Even so, they still represent a political position. This is what Carl-Friedrich Schleussner argues: "[What] is important to understand is that temperature targets are always political decisions based on value judgments about the trade-off between the desire to avoid climate impacts and the mitigation efforts required to achieve them.”

At this point, two questions need to be asked. The first is whether it makes sense to continue to bet on limits that seem improbable. Dr. Frank Rijsberman believes it does: "From a political point of view, the 1.5 degree target is still very important, largely symbolically, as a reminder of the urgency of taking action."

The second question is whether climate summits are the best tool to tackle the climate crisis. Thelma Krug, vice-chair of the IPCC and with countless summits under her belt as leader of the Brazilian negotiations, has a lot to say: "With so many years of involvement in this political process, I have learned that the speed at which decisions are made is far below the expectation of what the science says is urgent. But that is the price you pay for dealing with the climate issue in the UN.” She adds: "On the other hand, the UN allows every member government to have an equal voice; in my view, this is part of climate justice.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Stay up to date with DeSmog news and alerts